Micronlms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

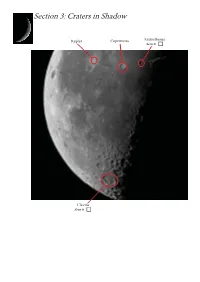

Craters in Shadow

Section 3: Craters in Shadow Kepler Copernicus Eratosthenes Seen it Clavius Seen it Section 3: Craters in Shadow Visibility: A pair of binoculars is the minimum requirement to see these features. When: Look for them when the terminator’s close by, typically a day before last quarter. Not all craters are best seen when the Sun is high in the lunar sky - in fact most aren’t! If craters aren’t par- ticularly bright or dark, they tend to disappear into the background when the Moon’s phase is close to full. These craters are best seen when the ‘terminator’ is nearby, or when the Sun is low in the lunar sky as seen from the crater. This causes oblique lighting to fall on the crater and create exaggerated shadows. Ultimately, this makes the crater look more dramatic and easier to see. We’ll use this effect for the next section on lunar mountains, but before we do, there are a couple of craters that we’d like to bring to your attention. Actually, the Moon is covered with a whole host of wonderful craters that look amazing when the lighting is oblique. During the summer and into the early autumn, it’s the later phases of the Moon are best positioned in the sky - the phases following full Moon. Unfortunately, this means viewing in the early hours but don’t worry as we’ve kept things simple. We just want to give you a taste of what a shadowed crater looks like for this marathon, so the going here is really pretty easy! First, locate the two craters Kepler and Copernicus which were marathon targets pointed out in Section 2. -

GURPS4E Ultra-Tech.Qxp

Written by DAVID PULVER, with KENNETH PETERS Additional Material by WILLIAM BARTON, LOYD BLANKENSHIP, and STEVE JACKSON Edited by CHRISTOPHER AYLOTT, STEVE JACKSON, SEAN PUNCH, WIL UPCHURCH, and NIKOLA VRTIS Cover Art by SIMON LISSAMAN, DREW MORROW, BOB STEVLIC, and JOHN ZELEZNIK Illustrated by JESSE DEGRAFF, IGOR FIORENTINI, SIMON LISSAMAN, DREW MORROW, E. JON NETHERLAND, AARON PANAGOS, CHRISTOPHER SHY, BOB STEVLIC, and JOHN ZELEZNIK Stock # 31-0104 Version 1.0 – May 22, 2007 STEVE JACKSON GAMES CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 4 Adjusting for SM . 16 PERSONAL GEAR AND About the Authors . 4 EQUIPMENT STATISTICS . 16 CONSUMER GOODS . 38 About GURPS . 4 Personal Items . 38 2. CORE TECHNOLOGIES . 18 Clothing . 38 1. ULTRA-TECHNOLOGY . 5 POWER . 18 Entertainment . 40 AGES OF TECHNOLOGY . 6 Power Cells. 18 Recreation and TL9 – The Microtech Age . 6 Generators . 20 Personal Robots. 41 TL10 – The Robotic Age . 6 Energy Collection . 20 TL11 – The Age of Beamed and 3. COMMUNICATIONS, SENSORS, Exotic Matter . 7 Broadcast Power . 21 AND MEDIA . 42 TL12 – The Age of Miracles . 7 Civilization and Power . 21 COMMUNICATION AND INTERFACE . 42 Even Higher TLs. 7 COMPUTERS . 21 Communicators. 43 TECH LEVEL . 8 Hardware . 21 Encryption . 46 Technological Progression . 8 AI: Hardware or Software? . 23 Receive-Only or TECHNOLOGY PATHS . 8 Software . 24 Transmit-Only Comms. 46 Conservative Hard SF. 9 Using a HUD . 24 Translators . 47 Radical Hard SF . 9 Ubiquitous Computing . 25 Neural Interfaces. 48 CyberPunk . 9 ROBOTS AND TOTAL CYBORGS . 26 Networks . 49 Nanotech Revolution . 9 Digital Intelligences. 26 Mail and Freight . 50 Unlimited Technology. 9 Drones . 26 MEDIA AND EDUCATION . 51 Emergent Superscience . -

Sky and Telescope

SkyandTelescope.com The Lunar 100 By Charles A. Wood Just about every telescope user is familiar with French comet hunter Charles Messier's catalog of fuzzy objects. Messier's 18th-century listing of 109 galaxies, clusters, and nebulae contains some of the largest, brightest, and most visually interesting deep-sky treasures visible from the Northern Hemisphere. Little wonder that observing all the M objects is regarded as a virtual rite of passage for amateur astronomers. But the night sky offers an object that is larger, brighter, and more visually captivating than anything on Messier's list: the Moon. Yet many backyard astronomers never go beyond the astro-tourist stage to acquire the knowledge and understanding necessary to really appreciate what they're looking at, and how magnificent and amazing it truly is. Perhaps this is because after they identify a few of the Moon's most conspicuous features, many amateurs don't know where Many Lunar 100 selections are plainly visible in this image of the full Moon, while others require to look next. a more detailed view, different illumination, or favorable libration. North is up. S&T: Gary The Lunar 100 list is an attempt to provide Moon lovers with Seronik something akin to what deep-sky observers enjoy with the Messier catalog: a selection of telescopic sights to ignite interest and enhance understanding. Presented here is a selection of the Moon's 100 most interesting regions, craters, basins, mountains, rilles, and domes. I challenge observers to find and observe them all and, more important, to consider what each feature tells us about lunar and Earth history. -

Pete Aldridge Well, Good Afternoon, Ladies and Gentlemen, and Welcome to the Fifth and Final Public Hearing of the President’S Commission on Moon, Mars, and Beyond

The President’s Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy PUBLIC HEARING Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY Monday, May 3, and Tuesday, May 4, 2004 Pete Aldridge Well, good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the fifth and final public hearing of the President’s Commission on Moon, Mars, and Beyond. I think I can speak for everyone here when I say that the time period since this Commission was appointed and asked to produce a report has elapsed at the speed of light. At least it seems that way. Since February, we’ve heard testimonies from a broad range of space experts, the Mars rovers have won an expanded audience of space enthusiasts, and a renewed interest in space science has surfaced, calling for a new generation of space educators. In less than a month, we will present our findings to the White House. The Commission is here to explore ways to achieve the President’s vision of going back to the Moon and on to Mars and beyond. We have listened and talked to experts at four previous hearings—in Washington, D.C.; Dayton, Ohio; Atlanta, Georgia; and San Francisco, California—and talked among ourselves and we realize that this vision produces a focus not just for NASA but a focus that can revitalize US space capability and have a significant impact on our nation’s industrial base, and academia, and the quality of life for all Americans. As you can see from our agenda, we’re talking with those experts from many, many disciplines, including those outside the traditional aerospace arena. -

Concert for Peace Celebrating the Spirit of Martin Luther King, Jr

Monday Evening, January 18, 2010, at 7:30 Distinguished Concerts International New York (DCINY) Iris Derke, Co-Founder and General Director Jonathan Griffith, Co-Founder and Artistic Director Presents Concert for Peace Celebrating the Spirit of Martin Luther King, Jr. Distinguished Concerts Orchestra International Distinguished Concerts Singers International JONATHAN GRIFFITH, DCINY Principal Conductor KARL JENKINS Requiem (55:00) Accompanied by the film “Requiem” ERIKA GRACE POWELL, Soprano CHERRY DUKE, Mezzo-Soprano GERAINT LLYR OWEN, Treble JAMES NYORAKU SCHLEFER, Shakuhachi 1. Introit 2. Dies Irae 3. The Snow of Yesterday 4. Rex Tremendae 5. Confutatis 6. From Deep in My Heart 7. Lacrimosa 8. Now As a Spirit 9. Pie Jesu 10. Having Seen the Moon 11. Lux Aeterna 12. Farewell 13. In Paradisum Intermission Please hold your applause until the end of the last movement. Avery Fisher Hall Please make certain your cellular phone, pager, or watch alarm is switched off. Lincoln Center KARL JENKINS The Armed Man: A Mass For Peace (63:00) Accompanied by the film “The Armed Man” ERIKA GRACE POWELL, Soprano CHERRY DUKE, Mezzo-Soprano ADAM RUSSELL, Tenor MARK WATSON, Bass-Baritone IMAM SHAMSI ALI, Muazzin 1. The Armed Man 2. A Call to Prayer 3. Kyrie 4. Save Me from Bloody Men 5. Sanctus 6. Hymn Before Action 7. Charge! 8. Angry Flames 9. Torches 10. Agnus Dei 11. Now the Guns Have Stopped 12. Benedictus 13. Better is Peace Please hold your applause until the end of the last movement. Notes on the Program Requiem of the haiku movements—“Having Seen KARL JENKINS the Moon” and “Farewell”—which incorpo - Born: February 17, 1944, Neath, Wales, UK rate the Benedictus and the Agnus Dei Accompanied by the film “Requiem” produced and respectively. -

Planetary Science : a Lunar Perspective

APPENDICES APPENDIX I Reference Abbreviations AJS: American Journal of Science Ancient Sun: The Ancient Sun: Fossil Record in the Earth, Moon and Meteorites (Eds. R. 0.Pepin, et al.), Pergamon Press (1980) Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta Suppl. 13 Ap. J.: Astrophysical Journal Apollo 15: The Apollo 1.5 Lunar Samples, Lunar Science Insti- tute, Houston, Texas (1972) Apollo 16 Workshop: Workshop on Apollo 16, LPI Technical Report 81- 01, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston (1981) Basaltic Volcanism: Basaltic Volcanism on the Terrestrial Planets, Per- gamon Press (1981) Bull. GSA: Bulletin of the Geological Society of America EOS: EOS, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union EPSL: Earth and Planetary Science Letters GCA: Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta GRL: Geophysical Research Letters Impact Cratering: Impact and Explosion Cratering (Eds. D. J. Roddy, et al.), 1301 pp., Pergamon Press (1977) JGR: Journal of Geophysical Research LS 111: Lunar Science III (Lunar Science Institute) see extended abstract of Lunar Science Conferences Appendix I1 LS IV: Lunar Science IV (Lunar Science Institute) LS V: Lunar Science V (Lunar Science Institute) LS VI: Lunar Science VI (Lunar Science Institute) LS VII: Lunar Science VII (Lunar Science Institute) LS VIII: Lunar Science VIII (Lunar Science Institute LPS IX: Lunar and Planetary Science IX (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute LPS X: Lunar and Planetary Science X (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute) LPS XI: Lunar and Planetary Science XI (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute) LPS XII: Lunar and Planetary Science XII (Lunar and Planetary Institute) 444 Appendix I Lunar Highlands Crust: Proceedings of the Conference in the Lunar High- lands Crust, 505 pp., Pergamon Press (1980) Geo- chim. -

Sing-Phoenix-Choral-Festival-2018

Program O Come, Let Us Sing Unto the Lord (1970) I Will Lift Up Mine Eyes (1970) Mountain View Presbyterian Church & Church of the Beatitudes Combined Choirs Jackie Huber, director; David Zych, collaborative pianist Sure On This Shining Night (2005) O Magnum Mysterium (1994) North Valley Chorale Eleanor Johnson, director; David Zych, collaborative pianist Les Chansons des Roses (1993) I. En une seule fleur II. Contre qui, rose III. De ton rêve trop plein The Saint Barnabas Singers Paul Lee, director Ave Maria (1997) Madrigali (1987) I. Ov’è, lass’, il bel viso? III. Amor, io sento l’alma Solis Camerata Dr. Kira Rugen, director **There will be a 15-minute intermission** Lux Aeterna (1997) I. Introitus II. In Te, Domine, Speravi III. O Nata Lux IV. Veni, Sancte Spiritus V. Agnus Dei – Lux Aeterna Mass Choir & Chamber Orchestra Stephen Schermitzler, conductor _________________________________________________________________________________ Please silence all noise-making devices and refrain from the use of flash photography and video recording during the performance. Out of respect for the performers, please hold your applause during all song cycles until the conclusion of the final movement. This performance is being professionally audio recorded by Clarke Rigsby. Thank you for your cooperation. Please join us for a free reception in Nelson Hall immediately following tonight’s performance. Chamber Orchestra Violin 1 Viola Double Bass Spencer Ekenes* Ann Thompson* Claudia Botterweg Hisami Iijima Janet Quiroz Zachary Bush Dana Zhou Dwight -

Explore 12 Great Lunar Targets Sharpen Your Observing Skills on the Moon’S Craters, Lava Flows, and an Elusive Letter X

Small-scope wonders 11 7 Explore 12 great lunar targets Sharpen your observing skills on the Moon’s craters, lava flows, and an elusive letter X. 2 1 by Michael E. Bakich he Moon offers something for every observer. It has a face that’s always changing. Following it telescopically T through a lunar month can be fascinating. Ironically, when the Moon is brightest (Full Moon) is the worst time to view it. From our perspective, the Sun is shining on the Moon from a point directly behind us, minimizing shad- ows and thus revealing scant detail. 4 The best lunar viewing times are from when the thin cres- 5 cent becomes visible after New Moon until about 2 days after First Quarter (evening sky) and from about 2 days before Last Quarter to almost New Moon (morning sky). Shadows are lon- ger then, and features stand out in sharp relief. 8 This is especially true along the Moon’s shadow line — called the terminator — which divides the light and dark portions. Before Full Moon, the terminator shows where sunrise is occur- 12 ring; after Full Moon, it marks the sunset line. 6 10 Along the terminator, you’ll see mountaintops protruding high enough to catch sunlight while the dark lower terrain sur- rounds them. On large crater floors, you can follow “wall shad- ows” cast by sides of craters hundreds of feet high. All these 1 Archimedes Crater lies at 30° north latitude centered between the features seem to change in real time, and the differences you eastern and western limbs. -

By JOHN WELLS a M E R I C a N C H R O N I C L E S

AMERICAN CHRONICLES THE 1965-1969 by JOHN WELLS Table of Contents Introductory Note about the Chronological Structure of American Comic Book Chronicles ................. 4 Note on Comic Book Sales and Circulation Data.......................................... 5 Introduction & Acknowledgements ............ 6 Chapter One: 1965 Perception................................................................8 Chapter Two: 1966 Caped.Crusaders,.Masked.Invaders.............. 69 Chapter Three: 1967 After.The.Gold.Rush.........................................146 Chapter Four: 1968 A.Hazy.Shade.of.Winter.................................190 Chapter Five: 1969 Bad.Moon.Rising..............................................232 Works Cited ...................................................... 276 Index .................................................................. 285 Perception Comics, the March 18, 1965, edition of Newsweek declared, were “no laughing matter.” However trite the headline may have been even then, it wasn’t really wrong. In the span of five years, the balance of power in the comic book field had changed dramatically. Industry leader Dell had fallen out of favor thanks to a 1962 split with client Western Publications that resulted in the latter producing comics for themselves—much of it licensed properties—as the widely-respected Gold Key Comics. The stuffily-named National Periodical Publications—later better known as DC Comics—had seized the number one spot for itself al- though its flagship Superman title could only claim the honor of -

Network Aesthetics

Network Aesthetics Network Aesthetics Patrick Jagoda The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London Patrick Jagoda is assistant professor of English at the University of Chicago and a coeditor of Critical Inquiry. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2016 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2016. Printed in the United States of America 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 34648- 9 (cloth) ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 34651- 9 (paper) ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 226- 34665- 6 (e- book) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226346656.001.0001 The University of Chicago Press gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Division of the Humanities at the University of Chicago toward the publication of this book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jagoda, Patrick, author. Network aesthetics / Patrick Jagoda. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 226- 34648- 9 (cloth : alkaline paper) ISBN 978- 0- 226- 34651- 9 (paperback : alkaline paper) ISBN 978- 0- 226- 34665- 6 (e- book) 1. Arts—Philosophy. 2. Aesthetics. 3. Cognitive science. I. Title. BH39.J34 2016 302.23'1—dc23 2015035274 ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48- 1992 (Permanence of Paper). This book is dedicated to an assemblage of friends—including the late-night conversational, the lifelong, and the social media varieties— to whom I am grateful for inspiration and discussion, collaboration and argument, shared meals and intellectual support. Whenever I undertake the difficult task of thinking through and beyond network form, I constellate you in my imagination. -

THE SHAPE and ELEVATION ANALYSIS of LUNAR CRATER's TRUE MARGIN. Bo Li1, Zongcheng Ling1, Jiang Zhang1, Zhongchen Wu1, Yuheng

46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2015) 1709.pdf THE SHAPE AND ELEVATION ANALYSIS OF LUNAR CRATER'S TRUE MARGIN. Bo Li1, Zongcheng Ling1, Jiang Zhang1, Zhongchen Wu1, Yuheng Ni1, Jian Chen1.1 Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Optical Astronomy and Solar-Terrestrial Environment; Insitute of Space Sciences, Shandong University, Weihai 264209, China, ([email protected]). Introduction: Although rare for Earth and other plane- 1(xk-1, yk-1) starting at an arbitrary point P0 (x0, y0). The tary bodies, impact cratering is a common geologic location of the center of the crater C is calculated from process in planetary evolution history. The Moon is its centroid, pockmarked with literally billions of craters, which 푘−1 푥 푘−1 푦 퐶 = 푖=0 푖, 퐶 = 푖=0 푖 range in size from microscopic pits on the surfaces of 푥 푘 푦 푘 rock specimens to huge, circular impact basins with The shape of a depression’s boundary is de- hundreds or even thounds of kilometers in diameter. scribed by the polar function r θ with the origin lo- Recognition and evaluation of the impact processes cated at C. In order to extract depressions’ shapes can provide an essential interpretive tool for under- based on just a few points we calculate its Fourier ex- standing planets and their geologic evolution [1]. The pansion [3]: 푘−1 푠푖푛 (푛∗휃 ) 푘−1 푐표푠 (푛∗휃 ) 푘 regular and irregular shape and morphology of crater 푎 = 푖=0 푖 ; 푏 = 푖=0 푖 ; 푟 = . in different ages retain key information (e.g., impact 푛 푘 푛 푘 0 휋 direction and velocity) of the impact processes during The fourier coefficients ai, and bi pertain to its shape. -

Graphical Evidence for the Solar Coronal Structure During the Maunder Minimum: Comparative Study of the Total Eclipse Drawings in 1706 and 1715

J. Space Weather Space Clim. 2021, 11,1 Ó H. Hayakawa et al., Published by EDP Sciences 2021 https://doi.org/10.1051/swsc/2020035 Available online at: www.swsc-journal.org Topical Issue - Space climate: The past and future of solar activity RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Graphical evidence for the solar coronal structure during the Maunder minimum: comparative study of the total eclipse drawings in 1706 and 1715 Hisashi Hayakawa1,2,3,4,*, Mike Lockwood5,*, Matthew J. Owens5, Mitsuru Sôma6, Bruno P. Besser7, and Lidia van Driel – Gesztelyi8,9,10 1 Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research, Nagoya University, 4648601 Nagoya, Japan 2 Institute for Advanced Researches, Nagoya University, 4648601 Nagoya, Japan 3 Science and Technology Facilities Council, RAL Space, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Harwell Campus, OX11 0QX Didcot, UK 4 Nishina Centre, Riken, 3510198 Wako, Japan 5 Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, RG6 6BB Reading, UK 6 National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, 1818588 Mitaka, Japan 7 Space Research Institute, Austrian Academy of Sciences, 8042 Graz, Austria 8 Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London, RH5 6NT Dorking, UK 9 LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, 92195 Meudon, France 10 Konkoly Observatory, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 1121 Budapest, Hungary Received 18 October 2019 / Accepted 29 June 2020 Abstract – We discuss the significant implications of three eye-witness drawings of the total solar eclipse on 1706 May 12 in comparison with two on 1715 May 3, for our understanding of space climate change. These events took place just after what has been termed the “deep Maunder Minimum” but fall within the “extended Maunder Minimum” being in an interval when the sunspot numbers start to recover.