Network Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crazy Narrative in Film. Analysing Alejandro González Iñárritu's Film

Case study – media image CRAZY NARRATIVE IN FILM. ANALYSING ALEJANDRO GONZÁLEZ IÑÁRRITU’S FILM NARRATIVE TECHNIQUE Antoaneta MIHOC1 1. M.A., independent researcher, Germany. Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Regarding films, many critics have expressed their dissatisfaction with narrative and its Non-linear film narrative breaks the mainstream linearity. While the linear film narrative limits conventions of narrative structure and deceives the audience’s expectations. Alejandro González Iñárritu is the viewer’s participation in the film as the one of the directors that have adopted the fragmentary narrative gives no control to the public, the narration for his films, as a means of experimentation, postmodernist one breaks the mainstream con- creating a narrative puzzle that has to be reassembled by the spectators. His films could be included in the category ventions of narrative structure and destroys the of what has been called ‘hyperlink cinema.’ In hyperlink audience’s expectations in order to create a work cinema the action resides in separate stories, but a in which a less-recognizable internal logic forms connection or influence between those disparate stories is the film’s means of expression. gradually revealed to the audience. This paper will analyse the non-linear narrative technique used by the In the Story of the Lost Reflection, Paul Coates Mexican film director Alejandro González Iñárritu in his states that, trilogy: Amores perros1 , 21 Grams2 and Babel3 . Film emerges from the Trojan horse of Keywords: Non-linear Film Narrative, Hyperlink Cinema, Postmodernism. melodrama and reveals its true identity as the art form of a post-individual society. -

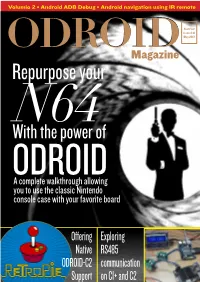

Magazine.Odroid.Com, Is Your Source for All Things Odroidian

Volumio 2 • Android ADB Debug • Android navigation using IR remote Year Four Issue #41 May 2017 ODROIDMagazine Repurpose your WithN64 the power of ODROID A complete walkthrough allowing you to use the classic Nintendo console case with your favorite board Offering Exploring Native RS485 ODROID-C2 communication Support on C1+ and C2 What we stand for. We strive to symbolize the edge of technology, future, youth, humanity, and engineering. Our philosophy is based on Developers. And our efforts to keep close relationships with developers around the world. For that, you can always count on having the quality and sophistication that is the hallmark of our products. Simple, modern and distinctive. So you can have the best to accomplish everything you can dream of. We are now shipping the ODROID-C2 and ODROID-XU4 devices to EU countries! Come and visit our online store to shop! Address: Max-Pollin-Straße 1 85104 Pförring Germany Telephone & Fax phone: +49 (0) 8403 / 920-920 email: [email protected] Our ODROID products can be found at http://bit.ly/1tXPXwe EDITORIAL o you have an old Nintendo or other gaming console that doesn’t work anymore? Don’t throw it away! You can re- Dfurbish it with an ODROID-XU4 running ODROID GameS- tation Turbo, RetroPie or Lakka and turn it into a multi-platform emulator station that can play thousands of different console games. Our main feature this month details how to fit everything into an N64 shell, breathing new life into an old dusty console case. ODROIDs are extremely versatile, and can be used for music playback, as de- scribed in our Volumio 2 article, developing Android apps, as Nanik demonstrates in his ar- ticle on the Android Debug Bridge, and process control, as shown by Charles and Neal in their discussion of the RS485 communication protocol. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Representations of Education in HBO's the Wire, Season 4

Teacher EducationJames Quarterly, Trier Spring 2010 Representations of Education in HBO’s The Wire, Season 4 By James Trier The Wire is a crime drama that aired for five seasons on the Home Box Of- fice (HBO) cable channel from 2002-2008. The entire series is set in Baltimore, Maryland, and as Kinder (2008) points out, “Each season The Wire shifts focus to a different segment of society: the drug wars, the docks, city politics, education, and the media” (p. 52). The series explores, in Lanahan’s (2008) words, an increasingly brutal and coarse society through the prism of Baltimore, whose postindustrial capitalism has decimated the working-class wage and sharply divided the haves and have-nots. The city’s bloated bureaucracies sustain the inequality. The absence of a decent public-school education or meaningful political reform leaves an unskilled underclass trapped between a rampant illegal drug economy and a vicious “war on drugs.” (p. 24) My main purpose in this article is to introduce season four of The Wire—the “education” season—to readers who have either never seen any of the series, or who have seen some of it but James Trier is an not season four. Specifically, I will attempt to show associate professor in the that season four holds great pedagogical potential for School of Education at academics in education.1 First, though, I will present the University of North examples of the critical acclaim that The Wire received Carolina at Chapel throughout its run, and I will introduce the backgrounds Hill, Chapel Hill, North of the creators and main writers of the series, David Carolina. -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

Why Every Show Needs to Be More Like the Wire (“Not Just the Facts, Ma’Am”)

DIALOGUE WHY EVERY SHOW NEEDS TO BE MORE LIKE THE WIRE (“NOT JUST THE FACTS, MA’AM”) NEIL LANDAU University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) The Wire (HBO, 2002-2008) upends the traditional po- ed the cop-drama universe. It was a pioneering season-long lice procedural by moving past basic plot points and “twists” procedural. Here are my top 10 reasons why Every Show in the case, diving deep into the lives of both the cops and Needs to Be More Like The Wire. the criminals they pursue. It comments on today’s America, employing characters who defy stereotype. In the words of — creator David Simon: 1. “THIS AMERICA, MAN” The grand theme here is nothing less than a nation- al existentialism: It is a police story set amid the As David Simon explains: dysfunction and indifference of an urban depart- ment—one that has failed to come to terms with In the first story arc, the episodes begin what the permanent nature of urban drug culture, one would seem to be the straightforward, albeit pro- in which thinking cops, and thinking street players, tracted, pursuit of a violent drug crew that controls must make their way independent of simple expla- a high-rise housing project. But within a brief span nations (Simon 2000: 2). of time, the officers who undertake the pursuit are forced to acknowledge truths about their de- Given the current political climate in the US and interna- partment, their role, the drug war and the city as tionally, it is timely to revisit the The Wire and how it expand- a whole. -

Pliego De Prescripciones Técnicas Del Contrato

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE BIBLIOTECAS, ARCHIVOS Y MUSEOS SUBDIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE BIBLIOTECAS, ARCHIVOS Y MUSEOS SERVICIO DE BIBLIOTECAS PÚBLICAS Página: 1 de 86 PLIEGO DE PRESCRIPCIONES TÉCNICAS DEL CONTRATO “SUMINISTRO DE MATERIAL AUDIOVISUAL Y MULTIMEDIA CON DESTINO A LAS BIBLIOTECAS DEL AYUNTAMIENTO DE MADRID” A ADJUDICAR POR PROCEDIMIENTO ABIERTO Expediente 300/2014/00397 1.- OBJETO DEL CONTRATO Adquisición de material audiovisual y multimedia (Blue-Ray, DVD, CD Audio y Código de verificación : PY3d3284c50e6008 DVD Audio) para la creación, actualización y mantenimiento de fondos de las bibliotecas municipales, según relación de títulos y número de ejemplares para cada título recogida en los Anexos I y II al presente Pliego de Prescripciones Técnicas La empresa que resulte adjudicataria suministrará el número de ejemplares de cada disco (Blue-Ray, DVD, CD Audio y DVD Audio) recogidos en el Anexo I y II con el descuento que haya presentado en su oferta. En caso de baja de adjudicación (de conformidad con el apartado 1 del Anexo I y II del Pliego de Cláusulas Administrativas Particulares) se deberá incrementar el número de unidades a suministrar de entre las relacionadas en el Anexo I y II del Presente Pliego de Prescripciones Técnicas. 2.- DURACION DEL CONTRATO La fecha prevista de inicio del contrato es el 1 de septiembre de 2014. La http://www- duración máxima del contrato será de 30 días hábiles contados desde el día siguiente a la formalización, sea esta anterior o posterior a la citada fecha prevista de inicio. 3.- LUGAR DE ENTREGA DEL SUMINISTRO Los suministros serán entregados en las condiciones que se detallan en este Pliego de Prescripciones Técnicas en las siguientes dependencias del Ayuntamiento de Madrid: Unidad Técnica de Bibliotecas Públicas. -

Network Aesthetics

Network Aesthetics: American Fictions in the Culture of Interconnection by Patrick Jagoda Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Supervisor ___________________________ Katherine Hayles ___________________________ Timothy W. Lenoir ___________________________ Frederick C. Moten Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 ABSTRACT Network Aesthetics: American Fictions in the Culture of Interconnection by Patrick Jagoda Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Supervisor __________________________ Katherine Hayles ___________________________ Timothy W. Lenoir ___________________________ Frederick C. Moten An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 Copyright by Patrick Jagoda 2010 Abstract Following World War II, the network emerged as both a major material structure and one of the most ubiquitous metaphors of the globalizing world. Over subsequent decades, scientists and social scientists increasingly applied the language of interconnection to such diverse collective forms as computer webs, terrorist networks, economic systems, and disease ecologies. The prehistory of network discourse can be -

Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2008-03-28 Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship Bradley R. Clark Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Clark, Bradley R., "Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship" (2008). Theses and Dissertations. 1350. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1350 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Using the ZMET Method 1 Running head: USING THE ZMET METHOD TO UNDERSTAND MEANINGS Using the ZMET Method to Understand Individual Meanings Created by Video Game Players Through the Player-Super Mario Avatar Relationship Bradley R Clark A project submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Brigham Young University April 2008 Using the ZMET Method 2 Copyright © 2008 Bradley R Clark All Rights Reserved Using the ZMET Method 3 Using the ZMET Method 4 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a project submitted by Bradley R Clark This project has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. -

The Wire the Complete Guide

The Wire The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 29 Jan 2013 02:03:03 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 The Wire 1 David Simon 24 Writers and directors 36 Awards and nominations 38 Seasons and episodes 42 List of The Wire episodes 42 Season 1 46 Season 2 54 Season 3 61 Season 4 70 Season 5 79 Characters 86 List of The Wire characters 86 Police 95 Police of The Wire 95 Jimmy McNulty 118 Kima Greggs 124 Bunk Moreland 128 Lester Freamon 131 Herc Hauk 135 Roland Pryzbylewski 138 Ellis Carver 141 Leander Sydnor 145 Beadie Russell 147 Cedric Daniels 150 William Rawls 156 Ervin Burrell 160 Stanislaus Valchek 165 Jay Landsman 168 Law enforcement 172 Law enforcement characters of The Wire 172 Rhonda Pearlman 178 Maurice Levy 181 Street-level characters 184 Street-level characters of The Wire 184 Omar Little 190 Bubbles 196 Dennis "Cutty" Wise 199 Stringer Bell 202 Avon Barksdale 206 Marlo Stanfield 212 Proposition Joe 218 Spiros Vondas 222 The Greek 224 Chris Partlow 226 Snoop (The Wire) 230 Wee-Bey Brice 232 Bodie Broadus 235 Poot Carr 239 D'Angelo Barksdale 242 Cheese Wagstaff 245 Wallace 247 Docks 249 Characters from the docks of The Wire 249 Frank Sobotka 254 Nick Sobotka 256 Ziggy Sobotka 258 Sergei Malatov 261 Politicians 263 Politicians of The Wire 263 Tommy Carcetti 271 Clarence Royce 275 Clay Davis 279 Norman Wilson 282 School 284 School system of The Wire 284 Howard "Bunny" Colvin 290 Michael Lee 293 Duquan "Dukie" Weems 296 Namond Brice 298 Randy Wagstaff 301 Journalists 304 Journalists of The Wire 304 Augustus Haynes 309 Scott Templeton 312 Alma Gutierrez 315 Miscellany 317 And All the Pieces Matter — Five Years of Music from The Wire 317 References Article Sources and Contributors 320 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 324 Article Licenses License 325 1 Overview The Wire The Wire Second season intertitle Genre Crime drama Format Serial drama Created by David Simon Starring Dominic West John Doman Idris Elba Frankie Faison Larry Gilliard, Jr. -

The Camera in 3D Video Games

University of Utah UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL DESIGNING FOR INTERACTIVITY: THE CAMERA IN 3D VIDEOGAMES Jackson Keller (Gabriel Olson) Department of Entertainment Arts and Engineering ABSTRACT This paper analyzes the effect that camera control has on art, design, and player experience in 3D video games. It will specifically explore the implications of various methods of camera control that have emerged during the brief history of 3D games: the first and third-person perspectives, fixed and filmic perspectives, abstract non-linear perspectives, and unique perspectives enabled by recent technological innovation, including Virtual and Augmented reality. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT I INTRODUCTION 3 THE EMERGENCE OF 3D VIDEO GAMES 4 THE THIRD-PERSON PERSPECTIVE 9 ALTERNATE APPROACHES TO THE CAMERA: IMITATING FILM 14 THE NON-LINEAR PERSPECTIVE: EXPERIMENTAL ART AND SIMULATED CAMERAS 20 THE IMPLICATIONS OF INNOVATION: MODIFICATION OF EXISTING PERSPECTIVES 22 CONCLUSION 24 SPECIAL THANKS 25 WORKS CITED 26 ii INTRODUCTION Both games and film are audiovisual media. One understanding of the medium of games is as a form of interactive movie, descending from the legacy of film. While games are certainly their own art form (The 2011 Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association Supreme Court decision gave video games first amendment protection as an art form), many games do contain filmic elements. However, interactivityi is central to the medium and generally takes precedence over aesthetic control. Most 3D games allow the player to control the camera, and the gameplay experience lacks the cinematographic precision of film. Designers craft levels to lead players towards game objectives, as well as composed aesthetic experiences when possible.