Download Thesisadobe PDF (583.09

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marco Balzarotti

MARCO BALZAROTTI (Curriculum Professionale liberamente fornito dall'utente a Voci.FM) link originale (thanks to): http://www.antoniogenna.net/doppiaggio/voci/vocimbal.htm Alcuni attori e personaggi doppiati: FILM CINEMA Spencer Garrett in "Il nome del mio assassino" (Ag. Phil Lazarus), "Il cammino per Santiago" (Phil) Viggo Mortensen in "American Yakuza" (Nick Davis / David Brandt) Michael Wisdom in "Masked and Anonymous" (Lucius) John Hawkes in "La banda del porno - Dilettanti allo sbaraglio!" (Moe) Jake Busey in "The Hitcher II - Ti stavo aspettando" (Jim) Vinnie Jones in "Brivido biondo" (Lou Harris) Larry McHale in "Joaquin Phoenix - Io sono qui!" (Larry McHale) Paul Sadot in "Dead Man's Shoes - Cinque giorni di vendetta" (Tuff) Jerome Ehlers in "Presa mortale" (Van Buren) John Surman in "I'll Sleep When I'm Dead" (Anatomopatologo) Anthony Andrews in "Attacco nel deserto" (Magg. Meinertzhagen) William Bumiller in "OP Center" (Lou Bender) Miles O'Keefe in "Liberty & Bash" (Liberty) Colin Stinton in "The Commander" (Ambasc. George Norland) Norm McDonald in "Screwed" Jeroen Krabbé in "The Punisher - Il Vendicatore" (1989) (Gianni Franco, ridopp. TV) Malcolm Scott in "Air Bud vince ancora" (Gordon) Robert Lee Oliver in "Oh, mio Dio! Mia madre è cannibale" (Jeffrey Nathan) John Corbett in "Prancer - Una renna per amico" (Tom Sullivan) Paul Schrier in "Power Rangers: Il film" e "Turbo - A Power Rangers Movie" (Bulk) Samuel Le Bihan in "Frontiers - Ai confini dell'inferno" (Goetz) Stefan Jürgens in "Porky college 2 - Sempre più duro!" (Padre di Ryan) Tokuma Nishioka in "Godzilla contro King Ghidora" (Prof. Takehito Fujio) Kunihiko Mitamura in "Godzilla contro Biollante" (Kazuhito Kirishima) Choi Won-seok in "La leggenda del lago maledetto" (Maestro Myo-hyeon) Eugene Nomura in "Gengis Khan - Il grande conquistatore" (Borchu) FILM D'ANIMAZIONE (CINEMA E HOME-VIDEO) . -

Margot Knight

MARGOT KNIGHT THEATRE: 2019 UNDERGROUND lead role: Nancy Wake Dir: Sara Grenfell Gasworks Theatre, Small Gems Tour 2016 THE WORLD WITHOUT BIRDS lead role: Queen of The Birds Dir: Elizabeth Wally La Mama 2012 THE EMPTY CHAIR co-lead Dir: Paul English by Alan Hopgood, Vic Regional Tour 2012 ICI co-lead Writer: Rebecca Lister Esplanade DuLac Theatre France Tour 2012 THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST Lady Bracknell Dir: Stig Wemyss Melbourne French Theatre 2011 HOME FOR LUNCH lead role Heather Director Luch Freeman @ Chapel Off Chapel 2010 THE PEPPERCORN TREE co-lead ‘Grace’, Dir: Lucy Freeman, Victorian Regional Tour 2007 CHOSEN VESSEL – PETTY TRAFFIKERS at Theatreworks Director Stewart Morritt 2006/2007 CONTROLLED CRYING (Lead role: Libby) Melb Season, Vic Tour, Seymour Centre Sydney. Director Joy Mitchell. 2007 WICKED WIDOWS (lead role) by Alan Hopgood. Victorian and metropolitan tour. 2007 FOUR FUNERALS IN ONE DAY - By Alan Hopgood. Melb Convention Centre 2007 THE LOWER DEPTHS – reading 45 Downstairs. Director Ariette Taylor. 2005/2006 A PILL A PUMP AND A NEEDLE by Alan Hopgood (Lead) Vict and interstate tour. 2005 IF I SHOULD DIE BEFORE I WAKE (Lead) Victorian Tour – Director Joy Mitchell. FRUITS OF LOVE – Reading. The Malthouse. 2001-2002 FOR BETTER FOR WORSE (Barbara) Tour Canberra & Victoria. Dir: Peter Adams 2000 BILLY POSSIBLE (Rebecca Worthchild) Director Joy Mitchell. Comedy Festival FOR BETTER FOR WORSE (Barbara) South Australia Tour & Tasmanian Tour 1998 FOR BETTER FOR WORSE (Barbra) Regional Tour THREE SCORE AND TEN (Sister Knightsley) Theatre In The Raw, Playbox 1997 FOR BETTER FOR WORSE (Barbra) Dir. Peter Adams, Chapel Off Chapel 1996 RICHARD II (Duke Of York) Dir. -

CICLO DE CINE La Voz De Constantino Romero II El Golpe George Roy Hill (1973) 2 De Agosto De 2013, 17.30 H

CICLO DE CINE La voz de Constantino Romero II El golpe George Roy Hill (1973) 2 de agosto de 2013, 17.30 h Título original: The Sting. Dirección: George Roy Hill. Productores: Tony Bill, Julia Phillips, Michael Phillips. Productores ejecutivos: David Brown, Richard D. Zanuck. Productor asociado: Robert Crawford Jr. Producción: Zanuck/Brown Productions, Universal Pictures. Guion: David S. Ward. Fotografía: Robert Surtees. Música: Scott Joplin, adaptado por Marvin Hamslisch. Montaje: William Reynolds. Dirección artística: Henry Bumstead. Intérpretes: Paul Newman (Henry Gondorff), Robert Redford (Johnny Hooker), Robert Shaw (Doyle Lonnegan), Charles Durning (teniente William Snyder), Ray Walston (J. J. Singleton), Eileen Brennan (Billie), Harold Gould (Kid Twist), John Heffernan (Eddie Niles), Dana Elcar (agente del F.B.I. Polk), Jack Kehoe, Dimitra Arliss, Robert Earl Jones, James Sloyan, Charles Dierkop, Lee Paul, Sally Kirkland, Avon Long, Arch Johnson, Ed Bakey, Brad Sullivan... Nacionalidad y año: Estados Unidos 1973. Duración y datos técnicos: 129 min. Color 1.85:1. Posiblemente El golpe sea una de las películas más populares de los setenta, y mucha gente la valore como una de las más ingeniosas, debido al siempre atractivo tema de los “pillos simpáticos” y la de los intrincados juegos de azar plagados de inventiva. Este mérito corresponde, desde luego, al guionista, David S. Ward, en ésta su segunda película, tras la muy poco conocida Material americano (Steelhard Blues, 1973), de Alan Myerson. No puede decirse, en todo caso, que tras El golpe (por el cual ganó un Oscar, y fue candidato a los premios Edgar Allan Poe, los Globo de Oro y la Writers Guild of America), tuviera una carrera demasiado lucida: su siguiente guion apareció en 1982, con Destinos sin rumbo (Cannery Row, 1982), su debut en la dirección, seguida de la secuela El golpe II (The Sting II, 1983), de un director que merece más crédito del que se le suele dar, Jeremy Kagan. -

Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm

JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 3 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm Edited by Cristina M. Giannantonio Amy E. Hurley-Hanson Associate Professors of Management, George L. Argyros School of Business and Economics, Chapman University, USA NEW HORIZONS IN LEADERSHIP STUDIES Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK + Northampton, MA, USA Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 1 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 4 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 © Cristina M. Giannantonio andAmy E. Hurley-Hanson 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by Edward Elgar Publishing Limited The Lypiatts 15 Lansdown Road Cheltenham Glos GL50 2JA UK Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. William Pratt House 9 Dewey Court Northampton Massachusetts 01060 USA A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946802 This book is available electronically in the ElgarOnline.com Business Subject Collection, E-ISBN 978 1 78100 212 4 ISBN 978 1 78100 211 7 (cased) Typeset by Columns Design XML Ltd, Reading Printed and bound in Great Britain by T.J. International Ltd, Padstow Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 2 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 1 SESS: 5 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:57:46 2013 14. Extreme leadership as creative leadership: reflections on Francis Ford Coppola in The Godfather Charalampos Mainemelis and Olga Epitropaki INTRODUCTION How do extreme leadership situations arise? According to one view, they are triggered by environmental factors that have nothing or little to do with the leader. -

Daily 23 Mar 07

ISSN 1834-3058 When flying the best price is Red. WE HAVE TEMPS AVAILABLE IN: Europe from $1,370* s SYD s BNE s ADL ON SALE NOW Travel DailyAU s MEL s PER Departures First with the news 01 Oct 08 - 15 Apr 09 *Conditions apply. Fare is net Mon 19 May 08 Page 1 CALL 1300 836 766 and does not include taxes, EDITORS: Bruce Piper and Guy Dundas FOR FURTHER INFORMATION fees and surcharges. E-mail: [email protected] Ph: 1300 799 220 QF boosts Syd-Tam QANTASLINK announced on the Destination Britain 2008 LAST CHANCE! welcome delegates to the event. weekend that from Aug it will TODAY scores of travel industry Destination Britain 2008’s major introduce its new Bombardier buyers from across the region sponsor is Eurostar, with other CLOSES TODAY Q400 on the Sydney-Tamworth have converged on Port Douglas backers including Qantas, North route, boosting capacity by 24%. in Tropical North Queensland for East England, visitScotland, and Narendra Kumar, Qantas Group the fifth annual Destination Britain showcase, staged by Tourism Ireland. WIN $250 gm regional airlines said the new The unique business to business aircraft will see an additional 660 VisitBritain. event is VisitBritain’s largest weekly seats on the route, taking For the first time the regional Travel Agents! overseas travel trade promotion - the total to 3360. event includes buyers from the and will also expose the buyers to Register now for your chance Tamworth will be the “first Middle East and Africa, following TNQ product while they’re here. to win a $250 gift voucher regional centre in NSW to have a shake-up in the structure of The format sees suppliers and Q400 services on a daily basis,” VisitBritain last year. -

Downloadable Text (Finkelstein and Mccleery 2006, 1)

A Book History Study of Michael Radford’s Filmic Production William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS of RHODES UNIVERSITY by BRYONY ROSE HUMPHRIES GREEN March 2008 ABSTRACT Falling within the ambit of the Department of English Literature but with interdisciplinary scope and method, the research undertaken in this thesis examines Michael Radford’s 2004 film production William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice using the Book History approach to textual study. Previously applied almost exclusively to the study of books, Book History examines the text in terms of both its medium and its content, bringing together bibliographical, literary and historical approaches to the study of books within one theoretical paradigm. My research extends this interdisciplinary approach into the filmic medium by using a modified version of Robert Darnton’s “communication circuit” to examine the process of transmission of this Shakespearean film adaptation from creation to reception. The research is not intended as a complete Book History study and even less as a comprehensive investigation of William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice . Rather, it uses a Shakespearean case study to bring together the two previously discrete fields of Book History and filmic investigation. Drawing on film studies, literary concepts, cultural and media studies, modern management theory as well as reception theories and with the use of both quantitative and qualitative data, I show Book History to be an eminently useful and constructive approach to the study of film. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank the Mandela Rhodes Foundation for the funding that allowed me to undertake a Master’s degree. -

Issue 17 Ausact: the Australian Actor Training Conference 2019

www.fusion-journal.com Fusion Journal is an international, online scholarly journal for the communication, creative industries and media arts disciplines. Co-founded by the Faculty of Arts and Education, Charles Sturt University (Australia) and the College of Arts, University of Lincoln (United Kingdom), Fusion Journal publishes refereed articles, creative works and other practice-led forms of output. Issue 17 AusAct: The Australian Actor Training Conference 2019 Editors Robert Lewis (Charles Sturt University) Dominique Sweeney (Charles Sturt University) Soseh Yekanians (Charles Sturt University) Contents Editorial: AusAct 2019 – Being Relevant .......................................................................... 1 Robert Lewis, Dominique Sweeney and Soseh Yekanians Vulnerability in a crisis: Pedagogy, critical reflection and positionality in actor training ................................................................................................................ 6 Jessica Hartley Brisbane Junior Theatre’s Abridged Method Acting System ......................................... 20 Jack Bradford Haunted by irrelevance? ................................................................................................. 39 Kim Durban Encouraging actors to see themselves as agents of change: The role of dramaturgs, critics, commentators, academics and activists in actor training in Australia .............. 49 Bree Hadley and Kathryn Kelly ISSN 2201-7208 | Published under Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) From ‘methods’ to ‘approaches’: -

Take a Summer Drive to Winter Skiing!

Take a Summer Drive to Winter Skiing! For Immediate Release: March 11, 2010: Spring might have sprung for some, but the winter sure isn’t over yet at Revelstoke Mountain Resort! Revelstoke is known for big spring snowfalls and late-season powder days, and a strong pacific front is knocking at the door! We have 4735 vertical feet of snow to ski, and lots of weather expected until our season comes to a close on April 11. The roads are clear, and we have even extended our March Madness Ski & Stay packages until April 11 to make it even easier for you to visit Revelstoke Mountain Resort – ski and stay mid-week at the Nelsen Lodge at the base of RMR from only $149 per person, or ski and stay at the Sandman Inn Revelstoke from $89 per person. Visit www.revelstokemountainresort.com for more details. While the snow is still falling at Revelstoke Mountain Resort, our Spring Events are heating up! Last weekend we hosted the Helly Hansen Big Mountain Battle, a GPS scavenger hunt around the mountain which was won by two ripping locals who will now represent RMR at the final Battle in the Bowls in Aspen, CO later this month. New this season, we are happy to offer the Spring Break Program for kids out of school for March Break. The Spring Break Program is the perfect forum for kids to improve their skills and have fun with kids their own age. The program is for skiers and snowboarders who are confident riding on green runs and more. -

108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: the Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film

Premiere of Dark Command, Lawrence, 1940. Courtesy of the Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History, Lawrence, Kansas. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 38 (Summer 2015): 108–135 108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: The Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film edited and introduced by Thomas Prasch ut the great fact was the land itself which seemed to overwhelm the little beginnings of human society that struggled in its sombre wastes. It was from facing this vast hardness that the boy’s mouth had become so “ bitter; because he felt that men were too weak to make any mark here, that the land wanted to be let alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar, savage kind of beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness” (Willa Cather, O Pioneers! [1913], p. 15): so the young boy Emil, looking out at twilight from the wagon that bears him backB to his homestead, sees the prairie landscape with which his family, like all the pioneers scattered in its vastness, must grapple. And in that contest between humanity and land, the land often triumphed, driving would-be settlers off, or into madness. Indeed, madness haunts the pages of Cather’s tale, from the quirks of “Crazy Ivar” to the insanity that leads Frank Shabata down the road to murder and prison. “Prairie madness”: the idea haunts the literature and memoirs of the early Great Plains settlers, returns with a vengeance during the Dust Bowl 1930s, and surfaces with striking regularity even in recent writing of and about the plains. -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

Biography: Jocelyn Pook

Biography: Jocelyn Pook Jocelyn Pook is one of the UK’s most versatile composers, having written extensively for stage, screen, opera house and concert hall. She has established an international reputation as a highly original composer winning her numerous awards and nominations including a Golden Globe, an Olivier and two British Composer Awards. Often remembered for her film score to Eyes Wide Shut, which won her a Chicago Film Award and a Golden Globe nomination, Pook has worked with some of the world’s leading directors, musicians, artists and arts institutions – including Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese, the Royal Opera House, BBC Proms, Andrew Motion, Peter Gabriel, Massive Attack and Laurie Anderson. Pook has also written film score to Michael Radford’s The Merchant of Venice with Al Pacino, which featured the voice of countertenor Andreas Scholl and was nominated for a Classical Brit Award. Other notable film scores include Brick Lane directed by Sarah Gavron and a piece for the soundtrack to Gangs of New York directed by Martin Scorsese. With a blossoming reputation as a composer of electro-acoustic works and music for the concert platform, Pook continues to celebrate the diversity of the human voice. Her first opera Ingerland was commissioned and produced by ROH2 for the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Studio in June 2010. The BBC Proms and The King’s Singers commissioned to collaborate with the Poet Laureate Andrew Motion on a work entitled Mobile. Portraits in Absentia was commissioned by BBC Radio 3 and is a collage of sound, voice, music and words woven from the messages left on her answerphone. -

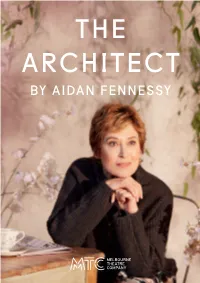

THE ARCHITECT by AIDAN FENNESSY Welcome

THE ARCHITECT BY AIDAN FENNESSY Welcome The Architect is an example of the profound role theatre plays in helping us make sense of life and the emotional challenges we encounter as human beings. Night after night in theatres around the world, audiences come together to experience, be moved by, discuss, and contemplate the stories playing out on stage. More often than not, these stories reflect the goings on of the world around us and leave us with greater understanding and perspective. In this world premiere, Australian work, Aidan Fennessy details the complexity of relationships with empathy and honesty through a story that resonates with us all. In the hands of Director Peter Houghton, it has come to life beautifully. Australian plays and new commissions are essential to the work we do at MTC and it is incredibly pleasing to see more and more of them on our stages, and to see them met with resounding enthusiasm from our audiences. Our recently announced 2019 Season features six brilliant Australian plays that range from beloved classics like Storm Boy to recent hit shows such as Black is the New White and brand new works including the first NEXT STAGE commission to be produced, Golden Shield. The full season is now available for subscription so if you haven’t yet had a look, head online to mtc.com.au/2019 and get your booking in. Brett Sheehy ao Virginia Lovett Artistic Director & CEO Executive Director & Co-CEO Melbourne Theatre Company acknowledges the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the Traditional Owners of the land on which Southbank Theatre and MTC HQ stand, and we pay our respects to Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors and Elders, and to our shared future.