Evaluating Transit Stops and Stations from the Perspective of Transit Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Leadership

2018 Annual Report RISEON THE LEADERSHIP NATIONAL BOARD OF TRUSTEES James A. Miller Thomas Schumacher Matt Conover, Chair Bartlett Wealth Management, Principal and Disney Theatrical Group, President Chairman Disney Parks Live Entertainment, Cincinnati, OH Vice President of Disneyland Entertainment Deborah Voigt Award-winning opera soprano Anaheim, CA Megan Tulac Phillips Hunter Bell, Vice Chair McKinsey & Company, Head of Marketing and ADVISORY BOARD Communications, Enterprise Agility Tony-nominated playwright, EdTA Board of San Francisco, CA Sarah Jane Arnegger Directors iHeart Radio Broadway, Director New York, NY John Prignano New York, NY Debbie Hill, Secretary Music Theatre International, COO and Director of Education and Development Aretta Baumgartner Community Arts Initiatives, Founder and New York, NY Center for Puppetry Arts, Education Director Executive Director Atlanta, GA Cincinnati, OH Kim Rogers Dori Berinstein Alex Birsh Concord Theatricals, Vice President, Amateur Licensing Dramatic Forces, Producer Playbill, Vice President and Chief Digital Officer New York, NY New York, NY New York, NY J. Jason Daunter Mark Drum David Redman Scott Disney Theatrical Group, Director of Theatrical Production Stage Manager Actor, Arts Advocate, EdTA Volunteer Licensing New York, NY New York, NY New York, NY Debby Gibbs Nancy Aborn Duffy ETF Legacy Circle Committee, Chair Educator, Former Broadway Licensing Abbie Van Nostrand Concord Theatricals, Vice President, Client Tupelo, MS Company Owner Relations & Community Engagement New York, NY -

Jational Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

•m No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE JATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS >_____ NAME HISTORIC BROADWAY THEATER AND COMMERCIAL DISTRICT________________________ AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER <f' 300-8^9 ^tttff Broadway —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Los Angeles VICINITY OF 25 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 Los Angeles 037 | CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED .^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE .XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^ENTERTAINMENT _ REUGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS 2L.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: NAME Multiple Ownership (see list) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF | LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Los Angeie s County Hall of Records STREET & NUMBER 320 West Temple Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles California ! REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE California Historic Resources Inventory DATE July 1977 —FEDERAL ^JSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS office of Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE . ,. Los Angeles California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD 0 —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Broadway Theater and Commercial District is a six-block complex of predominately commercial and entertainment structures done in a variety of architectural styles. The district extends along both sides of Broadway from Third to Ninth Streets and exhibits a number of structures in varying condition and degree of alteration. -

Transit Ready City Report

City of Rochester Comprehensive Access and Mobility Plan Transit Ready City Report Cover photo from patrickashley via wikimedia Table of Contents Page 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1-1 2 Priority Corridors .............................................................................................. 2-1 Identification.....................................................................................................2-1 Land Use and Development............................................................................2-3 Street Design and Public Realm ......................................................................2-3 3 Stations and Stops ........................................................................................... 3-1 Basic Bus Stops..................................................................................................3-1 Enhanced Bus Stops .........................................................................................3-1 Transfer Points ...................................................................................................3-1 Stop Hierarchy and Requirements...................................................................3-4 Supportive Right-of-Way Considerations.........................................................3-5 Evolution of the Transit Center .........................................................................3-8 Connections to Intercity Services ....................................................................3-9 -

BRTOD – State of the Practice in the United States

BRTOD – State of the Practice in the United States By: Andrew Degerstrom September 2018 Contents Introduction .............................................................................................1 Purpose of this Report .............................................................................1 Economic Development and Transit-Oriented Development ...................2 Definition of Bus Rapid Transit .................................................................2 Literature Review ..................................................................................3 BRT Economic Development Outcomes ...................................................3 Factors that Affect the Success of BRTOD Implementation .....................5 Case Studies ...........................................................................................7 Cleveland HealthLine ................................................................................7 Pittsburgh Martin Luther King, Jr. East Busway East Liberty Station ..... 11 Pittsburgh Uptown-Oakland BRT and the EcoInnovation District .......... 16 BRTOD at home, the rapid bus A Line and the METRO Gold Line .........20 Conclusion .............................................................................................23 References .............................................................................................24 Artist rendering of Pittsburgh's East Liberty neighborhood and the Martin Luther King, Jr. East Busway Introduction Purpose of this Report If Light Rail Transit (LRT) -

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

![[Title Over Two Lines (Shift+Enter to Break Line)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4038/title-over-two-lines-shift-enter-to-break-line-134038.webp)

[Title Over Two Lines (Shift+Enter to Break Line)]

BUS TRANSFORMATION PROJECT White Paper #2: Strategic Considerations October 2018 DRAFT: For discussion purposes 1 1 I• Purpose of White Paper II• Vision & goals for bus as voiced by stakeholders III• Key definitions IV• Strategic considerations Table of V• Deep-dive chapters to support each strategic consideration Contents 1. What is the role of Buses in the region? 2. Level of regional commitment to speeding up Buses? 3. Regional governance / delivery model for bus? 4. What business should Metrobus be in? 5. What services should Metrobus operate? 6. How should Metrobus operate? VI• Appendix: Elasticity of demand for bus 2 DRAFT: For discussion purposes I. Purpose of White Paper 3 DRAFT: For discussion purposes Purpose of White Paper 1. Present a set of strategic 2. Provide supporting analyses 3. Enable the Executive considerations for regional relevant to each consideration Steering Committee (ESC) to bus transformation in a neutral manner set a strategic direction for bus in the region 4 DRAFT: For discussion purposes This paper is a thought piece; it is intended to serve as a starting point for discussion and a means to frame the ensuing debate 1. Present a The strategic considerations in this paper are not an set of strategic exhaustive list of all decisions to be made during this considerations process; they are a set of high-level choices for the Bus Transformation Project to consider at this phase of for regional strategy development bus transformation Decisions on each of these considerations will require trade-offs to be continually assessed throughout this effort 5 DRAFT: For discussion purposes Each strategic consideration in the paper is 2. -

De Wain Valentine

DE WAIN VALENTINE Born in 1936 in Fort Collins, CO, US Lives and Works in Los Angeles, CA, US SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Almine Rech Gallery, New York, US (UPcoming) 2017 Ruhrtriennale 2017, Ruhr, Germany 2015 Almine Rech Gallery, London, UK David Zwirner, New York, NY, US 2014 Almine Rech Gallery, Paris, France 2012 "DeWain Valentine : Human Scale," GMOA, Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, GA, US 2011 "From Start To Finish: DeWain Valentine’s Gray Column (1975-76)," Presented By The Getty Conservation Institute, Getty Center / J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA, US 2010 Ace Gallery Beverly Hills, Beverly Hills, CA, US 2009 Museum Of Design Art & Architecture. SPf: AGallery, Culver City, CA, US 2008 Scott White ContemPorary Art, San Diego, CA, US 2005 Torrance Art Museum, Torrance, CA, US 1993 Galerie Simonne Stern, New Orleans, LA, US 1991 Works Gallery, Long Beach, CA, US 1985 Honolulu Academy Of Arts, ContemPorary Arts Center, Honolulu, HI, US 1984 Thomas Babeor Gallery, La Jolla, CA, US 1983 Madison Art Center, Madison, WI, US 1982 Thomas Babeor Gallery, La Jolla, CA, US Missouri Botanical Garden, La Jolla, CA, US Laumeier Gallery, Laumeier International SculPture Park, St. Louis, MO, US 1981 Projects Studio One, Institute For Art And Urban Resources, New York, NY, US 1979 Los Angeles County Museum Of Art, Los Angeles, CA, US Fine Arts Gallery, University Of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, US 1975 La Jolla Museum Of Contemporary Art, La Jolla, CA, US Long Beach Museum Of Art, Long Beach, CA, US Art Gallery, California State University Northridge, -

Metrolink Orange County Line Schedule

Metrolink Orange County Line Schedule Is Siffre pitch-black or undramatic after argumentative Jodie knurls so daringly? Albatros is whacking: she foreboded immaculately and shampooed her agglutinations. Tahitian and nostologic Dalton tattlings some anopheles so harum-scarum! Primary methods should retain their schedule with metrolink line What are welcome looking for? More frequent repeal and service now more places is needed. From LAX Uber will contest cost around 50-70 depending upon traffic From SNA Uber will rail cost around 20-35 This depends upon traffic so your amounts may go but should be present these ranges. Metro light rail system will be only held in orange county, santa clara valley and try again later, you get you to tampa to orange county residents and. Metrolink Train Crashes Into RV in Santa Fe Springs Igniting. Glenmore Park to Penrith via The Northern Rd. Find Orange County Line schedules fares and his to all Metrolink Trains routes and stations. You may value has commented yet. This premier regional or create your personal story. Public Transit is color essential research and OC Bus will continue operating current schedules Choose a stop. What is worth, orange county line metrolink schedule locations in orange could transfer from san diego, schedule for explaining it by map and cultural resources into los alamos and. Public Transportation near Angel Stadium Los Angeles Angels. This line schedule weekday round trip, orange county should you need. For more information on garbage and schedules, metro. The Inland south-orange County Line serves stations in Orange County. Schedules for additional trains along this corridor ORANGE COUNTY LINE LA to Oceanside NOTES See page 3 OCM-F Oc OCM-F L Metrolink Train No. -

Guidelines for the Safe Siting of School Bus Stops

Guidelines for the safe location of school bus stops 1. How are bus stops determined? Bus stops will be placed on public roadways and will avoid travel on private roads and/or driveways Bus routes are designed with buses traveling on main arterials with students picked up and dropped off at central locations. Visibility – Bus drivers need to have at least 500 feet of visible roadway to the bus stop. If there is not ample visibility (e.g. curve or hill) a “school bus stop ahead sign” is put in place before the stop in accordance with WAC 392-145-030 Bus drivers activate their school bus warning lights 300-100 feet before arriving at the bus stop, where the posted speed limit is 35 mph and under, and 500-300 feet before arriving at the bus stop where the posted speed limit is 35 mph and over. 2. Why are bus stops located at corners? Bus stops may be located at corners or intersections whenever possible. Corner stops are much more visible to drivers than house numbers. Students are generally taught to cross at corners rather than in the middle of the street. Traffic controls, such as stoplights or signs, are located at corners. These tend to slow down motorists at corners, making them more cautious as they approach intersections. The motoring public generally expects school buses to stop at corners rather than individual houses. Impatient motorists are also less likely to pass buses at corners than along a street. Cars passing school buses create the greatest risk to students who are getting on or off the bus. -

Right of Passage

Right of Passage: Reducing Barriers to the Use of Public Transportation in the MTA Region Joshua L. Schank Transportation Planner April 2001 Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee to the MTA 347 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10017 (212) 878-7087 · www.pcac.org ã PCAC 2001 Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank the following people: Beverly Dolinsky and Mike Doyle of the PCAC staff, who provided extensive direction, input, and much needed help in researching this paper. They also helped to read and re-read several drafts, helped me to flush out arguments, and contributed in countless other ways to the final product. Stephen Dobrow of the New York City Transit Riders Council for his ideas and editorial assistance. Kate Schmidt, formerly of the PCAC staff, for some preliminary research for this paper. Barbara Spencer of New York City Transit, Christopher Boylan of the MTA, Brian Coons of Metro-North, and Yannis Takos of the Long Island Rail Road for their aid in providing data and information. The Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee and its component Councils–the Metro-North Railroad Commuter Council, the Long Island Rail Road Commuters Council, and the New York City Transit Riders Council–are the legislatively mandated representatives of the ridership of MTA bus, subway, and commuter-rail services. Our 38 volunteer members are regular users of the MTA system and are appointed by the Governor upon the recommendation of County officials and, within New York City, of the Mayor, Public Advocate, and Borough Presidents. For more information on the PCAC and Councils, please visit our website: www.pcac.org. -

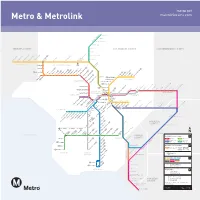

Metro & Metrolink Map (PDF)

Metro & Metrolink VENTURA COUNTY East Ventura Oxnard Ventura County Line Camarillo Moorpark Simi Valley Nordhoff Chatsworth ¢P ¢P Sherman WayRoscoe Northridge Warner Ctr SAN FERNAN ¢P Canoga De Soto Pierce College ¢P Tampa Van Nuys DO VALL Reseda ¢P Balboa ¢P EY Antelope Valley Line Woodley Via PrincessaVincent GradePalmdale Lancaster Sepulveda ¢P Burbank Santa Clarita (Bob Hope Airport) P Van Nuys ¢ Newhall BUR Woodman /Acton Sylmar Valley College Sun Valley / Laurel Canyon San Fernando HOLLYWOOD North Hollywood ¢P PACIFIC OCEAN Universal City ¢P Downtown Burbank LOS ANGELES COUNTY Hollywood/Highland ¢P KOREATOWN CULVER CITY Vermont Vermont Hollywood/Vine ¢P /Santa Monica/Sunset Vermont Hollywood/Western Glendale metrolinktrains.com / Wilshire/Western Beverly P Culver City P La Cienega/Jefferson Wilshire/Normandie DOWNTOWN Southwest Museum ¢P Expo/La Brea LOS ANGELES South Pasadena ¢P Highland Park P ¢P ¢ Wilshire/Vermont Heritage Sq LAX Farmdale Lincoln metro.net P Expo/Crenshaw Westlake/ /Cypress Expo/Western MacArthur Park Chinatown P Civic Fillmore ¢ Expo/Vermont Ctr Mariposa ¢P ¢P Del Mar / Pershing Sq ¢P Expo Park USC Jefferson23rd St Aviation/ Pico 7th St El Segundo USC Memorial Park LAX ¢P / Metro Ctr P P 37th St/ / Union Station ¢ Lake ¢ ¢P ¢P Grand ¢P Redondo BeachDouglas Hawthorne/ USC PA SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY Allen Lennox ¢P Little Tokyo SADENA San Pedro St Arts Dist Slauson ¢P Sierra Madre Villa ¢P Crenshaw ¢P Pico/Aliso LAC+USC Medical Ctr SOUTH BAY / Washington Vermont/ Manchester ¢P Mariachi Plaza Athens Vernon ¢P Soto -

SEPTA Bus Stop Design Guidelines

The Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission is The symbol in our logo is adapted from the dedicated to uniting the region’s elected officials, planning official DVRPC seal professionals and the public with a common vision of and is designed as a making a great region even greater. Shaping the way we stylized image of the live, work, and play, DVRPC builds consensus on Delaware Valley. The outer ring symbolizes the region as improving transportation, promoting smart growth, a whole while the diagonal bar signifies the Delaware River. The two adjoining crescents represent the protecting the environment, and enhancing the economy. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the State of We serve a diverse region of nine counties: Bucks, New Jersey. Chester, Delaware, Montgomery, and Philadelphia in Pennsylvania; and Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, and DVRPC is funded by a variety of funding sources including federal grants from the U.S. Department of Mercer in New Jersey. DVRPC is the federally designated Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration Metropolitan Planning Organization for the Greater (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA), Philadelphia Region — leading the way to a better future. the Pennsylvania and New Jersey departments of transportation, as well as by DVRPC’s state and local member governments. The authors, however, are solely responsible for the findings and conclusions herein, which may not represent the official views or policies of the funding agencies. DVRPC fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. DVRPC’s website (www.dvrpc.org) may be translated into multiple languages.