From Tangerine Dream to the Big Screen by Mr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clones Stick Together

TVhome The Daily Home April 12 - 18, 2015 Clones Stick Together Sarah (Tatiana Maslany) is on a mission to find the 000208858R1 truth about the clones on season three of “Orphan Black,” premiering Saturday at 8 p.m. on BBC America. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., April 12, 2015 — Sat., April 18, 2015 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING Friday WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 6 p.m. FS1 St. John’s Red Storm at Drag Racing WCIQ 7 10 4 Creighton Blue Jays (Live) WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Saturday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 7 p.m. ESPN2 Summitracing.com 12 p.m. ESPN2 Vanderbilt Com- WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 NHRA Nationals from The Strip at modores at South Carolina WEAC 24 24 Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Las Gamecocks (Live) WJSU 40 4 4 40 Vegas (Taped) 2 p.m. -

Tangerine Dream:News DPS 06/02/2009 11:39 Page 24 • • • • • • Music Live

Feb Cover:Cover 09/02/2009 09:27 Page 1 February 2009 entertainment, presentation, communication www.lsionline.co.uk Gothic Masterpiece L&SI visits Wills Memorial Hall, Bristol Prize Production Leeds Academy Monte Carlo Jazz Audio Networking Nobel Celebrations, Oslo L&SI visits a venue reborn Digital Mixing . nice. A Technical Focus update PLUS: Crunch Talks; PLASA as Awarding Body; TourTalk; Green Room; Gatecrasher & Ministry L&SI has gone digital! Register online FREE at www.lsionline.co.uk/digital News Tangerine Dream:News DPS 06/02/2009 11:39 Page 24 • • • • • • music live Picture House Dreams Since their formation in 1967, “When Walt Whitman wrote ‘I Sing The Body widespread and, ultimately, commonplace: “From Electric’ he could never have imagined the that chaos situation up to what we could call nearly contemporary reality of that phrase - a perfect setting of sequences, harmonies, Tangerine Dream have melodies, sound structures, and soundscapes that electronics will be opening even broader you can bring onstage today, I had to decide for horizons in the future and Tangerine Dream constantly evolved to retain myself and the band which way to go: are we in that will have been the first pioneers.” specific field of experimental song-orientated music just because we like it, or do we have to work with a fresh sound. Jonathan Miller Tangerine Dream: these words conjure up images the audience to get them participating in what we of a bygone psychedelic era. Yet this long-lasting, really do? caught up with the latest innovative German group has eagerly harnessed the latest technological developments in an “So we decided to experiment more, using the toys ongoing quest to remain on the cutting edge of surrounding us and developing new stuff ourselves; incarnation of the band at music production and performance for four and in doing so we felt obliged to perform again, decades, always prolific in recorded output while but it was a question of how to go about doing that Edinburgh’s Picture House . -

Tangerine Dream Force Majeure the Autobiography by Edgar Froese

Download File PDF Tangerine Dream Force Majeure The Autobiography By Edgar Froese Tangerine Dream Force Majeure The Autobiography By Edgar Froese File Name: tangerine dream force majeure the autobiography by edgar froese Size : 3264 KB Type : PDF, ePub, eBook Category : Book Uploaded : 2020-09-23 Rating : 4.6/5 From 635 votes Status: AVAILABLE Last checked: 37 Minutes ago! In order to read or download test, you need to create a FREE account DOWNLOAD NOW Book Descriptions: We have made it easy for you to find a PDF Ebooks without any digging. And by having access to our ebooks online or by storing it on your computer, you have convenient answers with . To get started finding , you are right to find our website which has a comprehensive collection of manuals listed. Our library is the biggest of these that have literally hundreds of thousands of different products represented. Value of Registration: 1. Register a free 1 month Trial Account. 2. Download as many books as you like (Personal use) 3. Cancel the membership at any time if not satisfied. 4. Join Over 80000 Happy Readers Page 1/2 Download File PDF Tangerine Dream Force Majeure The Autobiography By Edgar Froese A little people may be laughing as soon as looking at you readingtangerine dream force majeure the autobiography by edgar froese in your spare time. Some may be admired of you. And some may want be as soon as you who have reading hobby. What about your own feel? Have you felt right? Reading is a need and a leisure interest at once. -

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006 Jonathan R. Polansky Stanton Glantz, PhD CENTER FOR TOBAccO CONTROL RESEARCH AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94143 April 2007 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Smoking among American adults fell by half between 1950 and 2002, yet smoking on U.S. movie screens reached historic heights in 2002, topping levels observed a half century earlier.1 Tobacco’s comeback in movies has serious public health implications, because smoking on screen stimulates adolescents to start smoking,2,3 accounting for an estimated 52% of adolescent smoking initiation. Equally important, researchers have observed a dose-response relationship between teens’ exposure to on-screen smoking and smoking initiation: the greater teens’ exposure to smoking in movies, the more likely they are to start smoking. Conversely, if their exposure to smoking in movies were reduced, proportionately fewer teens would likely start smoking. To track smoking trends at the movies, previous analyses have studied the U.S. motion picture industry’s top-grossing films with the heaviest advertising support, deepest audience penetration, and highest box office earnings.4,5 This report is unique in examining the U.S. movie industry’s total output, and also in identifying smoking movies, tobacco incidents, and tobacco impressions with the companies that produced and/or distributed the films — and with their parent corporations, which claim responsibility for tobacco content choices. Examining Hollywood’s product line-up, before and after the public voted at the box office, sheds light on individual studios’ content decisions and industry-wide production patterns amenable to policy reform. -

Bridging Resources for Year 11 Applicants: Media Studies St John Rigby College Gathurst Rd, Orrell, Wigan WN5 0LJ 01942 214797

Bridging Resources for Year 11 Applicants: MEDIA STUDIES St John Rigby College Media Studies In Media, you will study a range of print and audio-visual products, including advertising, television, radio, film, newspapers and magazines, games and online media. The tasks below focus on some of these media types to give you some knowledge of them before beginning the course. We also have an online learning area with lots of fun and interesting tasks. If you would like access to this, please email us for login information. If you have any questions or would like more information about the course, please do get in touch! Simon Anten- Head of Media - [email protected] Catherine Strong- Media Teacher - [email protected] Music Video From its beginnings, music video has been an innovative and experimental form. Many a successful film director has either made their name as a music video director or still uses the form to experiment with editing, photography and post production effects. Watch the following two videos by British film directors: Radiohead’s “Street Spirit” (Jonathan Glazer 1995) and FKA Twigs’ “tw-ache” (Tom Beard 2014). What are your thoughts about both videos? In what ways might they be seen as experimental (as well as weird, intriguing and exciting)? How do they create an impact? How do they complement or challenge the music? Who is the target audience for each video? (It can be useful to read the comments on YouTube to get a sense of people’s reactions to them, but don’t do this if you’re sensitive to bad language!) Is there anything distinctly British about either or both of them? Comparing a director’s video and film output Jonathan Glazer directed Radiohead’s “Street Spirit” just a few years before directing his first feature, the brilliant Sexy Beast (2000), starring Ben Kingsley and Ray Winstone. -

Crossword Cryptoquip Seek and Find Jumble Movies

B8 THE NEWS-ENTERPRISE CLASSIFIEDS FRIDAY, MARCH 9, 2012 CROSSWORD FRIDAY EVENING March 9, 2012 Cable Key: E-E’town/Hardin/Vine Grove/LaRue R/B-Radcliff/Fort Knox/Muldraugh/Brandenburg E R B 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 HCEC 2 25 2 Drama Club John Hardin Prom Fashion Show Marquee Hardin County Focus-Finance Bridges Over Elizabethtown City Council Meeting WAVE 3 News at College Basketball SEC Tournament, Third Quarterfinal: Teams TBA. From New Orleans. (N) College Basketball SEC Tournament, Fourth Quarterfinal: Teams TBA. From WAVE 3 News at WAVE 3 6 3 7 (N) (CC) (Live) New Orleans. (N) (Live) 11 (N) Entertainment To- Inside Edition (N) Shark Tank Body jewelry; organic skin Primetime: What Would You Do? (N) 20/20 (N) (CC) High School Ga- (:35) Nightline (N) Jimmy Kimmel WHAS 11 4 11 night (N) (CC) care. (N) (CC) (CC) metime (CC) Live (CC) Wheel of Fortune Jeopardy! (N) Undercover Boss Oriental Trading Co. The Mentalist A terminally ill sales- Blue Bloods Erin and Danny face WLKY News at (:35) Late Show With David Letter- WLKY 5 5 5 (N) (CC) (CC) CEO Sam Taylor. (N) (CC) man is murdered. (N) (CC) each other in court. (N) (CC) 11:00PM (N) man (CC) Two and a Half The Big Bang Kitchen Nightmares “Blackberry’s; Leone’s” Improving a New Jersey eatery. WDRB News at (:45) WDRB Two and a Half 30 Rock “The Col- The Big Bang WDRB 12 9 12 Men (CC) Theory (CC) (PA) (CC) Ten (N) Sports Men (CC) lection” (CC) Theory (CC) Cold Case “November 22” Pool hus- Cold Case “The Long Blue Line” Mur- Cold Case An unkown killer commits a Cold Case The shipboard death of a Word Alive Friday Sports WBNA 6 21 10 tler’s killing examined. -

CD Review: Tangerine Dream ~ Paradiso

CD Review: Tangerine Dream ~ Paradiso http://www.vintagerock.com/classiceye/td_paradiso.aspx Home About Us Forum Listening Room Giveaways Links Contact Us Paradiso Tangerine Dream How could any red-blooded American male forget those delicious scenes of Tom Cruise atop a writhing Rebecca De Mornay in the movie Risky Business (remember the ‘choo choo’ train scene?). Behind all that carnal mayhem pulsed the intricate ethereal soundtrack provided by seminal “krautrock” band Tangerine Dream. Twenty years later, with countless albums under their belts, Tangerine Dream has released Paradiso, based on the third part of Dante Alighieri’s “La Divina Commedia” (Dante’s “Devine Comedy” for us layman). The creator and only original member through every incarnation of Tangerine Dream, Edgar Froese teamed up with fellow West Berlin underground ‘arty’ types in the late 1960’s. Forming TD after studying under Salvador Dali, of all people, Froese and company were one of the first purveyors of what has been termed “krautrock.” Froese welcomed various members into the ‘Dream’ fold over the years, most notably, Christopher Franke and Peter Baumann and most TD listeners — even those of us with only a passing knowledge of the band — recognize their pulsating synths. Tangerine Dream actually gained a solid reputation through their soundtracks for movies like Legend, The Keep and Risky Business, and continue to tour (as members come and go) with multimedia live performances. As testament to Froese, it is said he welcomes new members as writing contributors and not just players (as he did with Franke and Baumann). On the double CD Paradiso, however, Froese composed and produced all of the music. -

Until the End of the World Music Credits

(Below are the credits for the music in the English version, followed by the credits, in German, for the extended restored version): English-language music credits: Musical Score Graeme Revell Musical Score Graeme Revell Solo Cello and Additional Improvisation David Darling Music Supervision Gary Goetzman and Sharon Boyle Picture and Music Editor Peter Przygodda MUSIC Music Coordinators Barklie K. Griggs Jennifer Quinn-Richardson Dana K. Sano Music Recording and Mixing Studios Tritonus Studios, Berlin Music Editor (Synch) Dick Bernstein (Offbeat Systems) Music Mixing Engineer Gareth Jones 2nd Sound Engineer Gerd Krüger Assistant Maro Birkner Additional Music Recordings Hansa Tonstudios, Berlin MUSIC TITLES IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE: "GALKAN" Appears on "Les Aborigènes, Chants et Danses de l'Australie du Nord" Phonogramme ARN 64056 Courtesy of Arion "SAX & VIOLINS" Performed by Talking Heads Lyrics and Music by David Byrne Music by Chris Frantz, Jerry Harrison, Tina Weymouth Producer Steve Lillywhite and Talking Heads Mixed by Kevin Killen Publisher Bleu Disque Music Co. Inc./ Index Music admin. by WB Music Corp./ASCAP Courtesy of Warner Bros. Records Inc./Sire Records Company/FLY Talking Heads Appear Courtesy of EMI Records Ltd. "SUMMER KISSES, WINTER TEARS" Performed by Elvis Presley Writers Jack Lloyd, Ben Weissman, Fred Wise Publisher WB Music Corp./Erica Music/ ASCAP Courtesy of RCA Records Label of BMG Music "MOVE WITH ME" Performed by Neneh Cherry Writers Neneh Cherry/Cameron Mcvey Producer Booga Bear/Jonny Dollar Publisher Virgin Music Ltd/Copyright Control/ BMI/PRS Courtesy of Circa Records, Ltd. "IT TAKES TIME" Performed by Patti Smith and Fred Smith Writers Fred Smith and Patti Smith Producer Fred Smith Publisher Druse Music Inc/Stratium Music, Inc./ASCAP Courtesy of Arista Records, Inc. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

No Escape Music Credits

Music Composed by Graeme Revell Music Editor Dick Bernstein Assistant Music Editor Philip Tallman Music Recorded and Mixed at C. T. S. Studios, Wembley England Score Engineered and Mixed by Keith Grant Conductor and Orchestrator Tim Simonec Musicians Assembled by Nat Peck “Boogie Shoes” Written by Harry W. Casey and Richard Finch Published by Longitude Music Co. Performed by K. C. and the Sunshine Band Courtesy of Rhino Records, Inc. By Arrangement with Warner Special Products “Son of A Preacher Man” Written by John Hurley and Ronnie Wilkins Published by Tree Publishing Co., Inc. Performed by Dusty Springfield Courtesy of Atlantic Recording Corp. By Arrangement with Warner Special Products “Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone” Written by Dave Kirby and Glenn Martin Published by Tree Publishing Co., Inc. Performed by Doug Sahm Courtesy of Atlantic Recording Corp. By Arrangement with Warner Special Products CD: A CD of the score was released by Varèse Sarabande in the US (VSD-5483) and in Germany (VSD-5483) in 1994: Music composed by Graeme Revell Album produced by Graeme Revell Executive album producer Robert Towsnon Orchestrations: Tim Simonec and Graeme Revell Sampling: Brian Williams Music editors: Dick Bernstein and Philip Tallman Scoring mixer: Keith Grant Orchestra conducted by Tim Simonec Orchestra contracted by Nat Peck 1. No Escape: Main Titles (1’58”) 2. Helicopter To Absolom (2’13”) 3. Robbins Captured By The Outsiders (1’52”) 4. Ralph: Director Of Aquatic Activities (0’48”) 5. The Father (1’55”) 6. The Insiders’ Camp (1’34”) 7. “Wet Dreams” (2’05”) 8. “I Love Those Boots” (Twelve-string guitar - Philip Tallman) (1’47”) 9. -

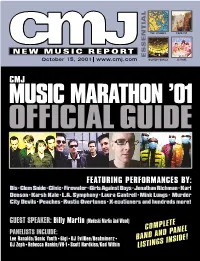

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

Winterspell Playlist 1. Sweet Dreams

Winterspell Playlist 1. Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) – Sucker Punch – performed by Emily Browning 2. Towers of the Void – Red Riding Hood – Brian Reitzell 3. Is It Poison, Nanny – Sherlock Holmes – Hans Zimmer 4. Dyslexia – Percy Jackson & the Olympians – Christophe Beck 5. Maria Redowa – Little Women – Thomas Newman 6. La Fayette’s Welcome – Little Women – Thomas Newman 7. Port Royal Gallop – Little Women – Thomas Newman 8. Dead Sister – Red Riding Hood – Brian Reitzell & Alex Heffes 9. The Dance – Emma – Rachel Portman 10. Tavern Stalker – Red Riding Hood – Brian Reitzell & Alex Heffes 11. Wolf Attack Suite – Red Riding Hood – Brian Reitzell & Alex Heffes 12. Then Came the Purge – Underworld: Awakening – Paul Haslinger 13. The Wolve’s Den – Underworld: Rise of the Lycans – Paul Haslinger 14. The Lycan Van Escape – Underworld: Awakening – Paul Haslinger 15. Wtf – Green Zone – John Powell 16. Mike to Tavern – Underworld: Evolution – Marco Beltrami 17. Darkness Deep Within – Underworld – Paul Haslinger 18. Teahouse – The Matrix Reloaded – Juno Reactor and Gocoo 19. To Jerusalem – Kingdom of Heaven – Harry Gregson-Williams 20. Jean and Logan – X-Men: The Last Stand – John Powell 21. Dissolve – The Book of Eli – Atticus Ross 22. Pier 17 – The Adjustment Bureau – Thomas Newman 23. Blind Faith – The Book of Eli – Atticus Ross 24. Richardson – The Adjustment Bureau – Thomas Newman 25. The Journey – The Book of Eli – Atticus Ross 26. Mt. Grimoor – Red Riding Hood – Brian Reitzell & Alex Heffes 27. The Arrow Attack – Underworld: Rise of the Lycans – Paul Haslinger 28. Corvinus – Underworld – Paul Haslinger 29. Subterrania – Underworld – Paul Haslinger 30. A Thorough Education – Jane Eyre – Dario Marianelli 31.