Implementation of Welfare Reform by Local Authorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

Cottingham and Middleton News

Cottingham and Middleton News November 2013 Available online at www.cottinghamnews.co.uk Welcome to this, my Green Horizons for young people By Andy Gilgrist 50th issue of the village newsletter. An empty field on Mill Road is being turned into a haven for children with The main talking point autism in a pioneering venture by in the villages at the their parents. moment is clearly the proposed housing development. Cottingham’s Jan and Andy Mears You can find answers to some of and Lucie Middlebrook have joined the questions you may have in the forces with three other local families centre pages. to create the Green Horizons project. You can keep up to date on this and all the latest village news on The idea is to give the young the village website, where you can Next issue people a place where they can also join the village email list to develop new horticultural and receive updates direct to your October 2013 animal husbandry skills to be active inbox. and productive in ways they find Andy Sawford MP (centre) with Green Horizons families fulfilling. Jane Smith, Editor 3 Corby Road, tel: 770821 Jan explained: “As children with autism grow up, the help and support they receive during school years comes to an end. For children who will struggle to find conventional employment, the world [email protected] can become narrower and less welcoming. Heritage Open Day “We were all talking about what we could do to give them a more productive future. We don’t want them to be limited to what is currently available, or to sit at home all day. -

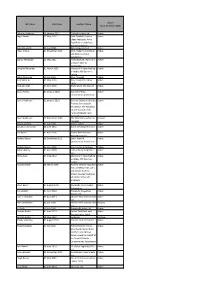

MP Name Start Date Landlord Name Status (As at 31

Status MP Name Start date Landlord Name (as at 31 March 2013) Debbie Abrahams 14 January 2011 Clayhall Estates Ltd Active Nigel Adams 17 May 2010 Ruth Elizabeth Sayner, Active Eileen Metcalfe, Anne Boyd Palmer and Peter Norman Sparling Bob Ainsworth 02 July 2008 JBC Computers Ltd Active Peter Aldous 01 November 2010 John Frederick Fitz Miller Active and Nicholas Ralph Oglethorpe Danny Alexander 15 May 2011 Inverness East, Nairn and Active Lochaber Liberal Democrats Douglas Alexander 01 March 2002 Marcus W F Dean trading Active as Abbey Mill Business Centre Heidi Alexander 19 July 2010 John Chappell Active Rushanara Ali 07 May 2010 Tower Hamlets Labour Active Party Graham Allen 01 April 2009 Nottingham City Council Active David Amess 01 January 2010 Southend West Active Conservative Association David Anderson 31 January 2013 Durham Diocesan Board of Active Finance as Custodian Trustee for The Parochial Church Council of the Parish of Blaydon and Swalwell David Anderson 25 November 2006 The Official Custodian for Inactive Charities Stuart Andrew 01 July 2010 James Liptrot Active Jonathan Ashworth 24 June 2011 Dasim Developments Ltd Active Ian Austin 01 April 2006 Dudley Metropolitan Active Borough Council Richard Bacon 08 December 2011 South Norfolk Active Conservative Association Richard Bacon 05 April 2009 R G L Taylor & Partners Active Adrian Bailey 01 April 2008 Labour Party Properties Active Ltd Willie Bain 04 June 2010 Marcus W F Dean trading Active as Abbey Mill Business Centre Norman Baker 08 March 2006 Andrew Stephen Goodwin, Active -

EARLY HELP and PREVENTION Children's Centre Venues

Agenda Item No: 09 – Appendix B EARLY HELP AND PREVENTION Children’s Centre Venues Consultation Response Analysis Report Author Sheila Sturgeon, Policy and Projects Officer, Early Help and Prevention Date 5th January 2015 1. Introduction 1.1. It is proposed that we make changes to the opening hours of some Children’s Centres, and in five cases, to the venues being used for some universal and for targeted Children’s Centre services. 1.2. Earlier this year our new model of delivering Children’s Centres came into effect, following extensive consultation over 12 weeks in the summer of 2013, which was supportive of the new model, and a commissioning process in the spring of this year 1. As a result, some of the services previously found in Children’s Centres are now delivered from our 36 libraries, and early help targeted Children’s Centre services to families in need of additional support are delivered by commissioned providers. 1.3. The early help targeted Children’s Centre services have been using all designated venues alongside universal services from our health and JobCentre Plus partners. The providers of our targeted services (Action for Children and Spurgeons) will spend much more time with families and children in and nearer to their homes and this means that they want to deliver less in the Children’s Centre buildings. To achieve this we propose to change the hours that some buildings are open , and to move services to entirely new venues in a very small number of cases. 1.4. NCC has a statutory duty to consult upon ‘major changes’ to the Children’s Centre provision 2. -

Annual General Meeting Agenda 1

WOODCROFT SCOUT CENTRE, KETTERING Wednesday 28th June 2017 at 7.30 pm ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING AGENDA 1. Welcome 2. Prayers 3. Apologies 4. Approval of minutes of the AGM in 2016 5. Chairman‟s Remarks 6. District Commissioner‟s Remarks 7. Treasurer‟s Remarks 8. Adoption of Reports a. Sectional Reports b. Financial Reports 9. Election of President 10. Election of Vice Presidents 11. To approve DC‟s nomination for District Chairman 12. Election of District Secretary 13. Election of District Treasurer 14. Election of Representatives to the District Executive Committee 15. To approve DC‟s nominations to the District Executive Committee 16. Election of Co-opted members to the District Executive Committee 17. Election of Representative to the County Scout Council 18. Election of District Nomination to the County Executive Committee 19. Appointment of District Independent Examiner 20. The County Commissioner 21. Presentations and Awards 22. Mayoral Comments 23. Date of 2018 Annual General Meeting Wednesday 27th June 2018 Minutes of the 2016 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Wednesday 29th June 2016 at 7.30 pm Woodcroft Scout Centre, Kettering Present – Mr C Jervis (Chairman), Mrs K Sloan (Secretary), Mr P Candlin (Treasurer), Mr J Masters (District Commissioner), Councillor Julie Riley Mayor of Corby and Consort Mr Bob Riley. Vice Presidents: The Rev Helen Wakefield-Carr & Trevor Wayman, Tony Keay (County Commissioner), Bob Peden (Deputy County Commissioner), Bob Townson, Karen Law, Christine Francis, Kim Pearce, 39 Scouters, SASU, Network & Explorer Scouts, lay members and guests 1. Welcome - The chairman welcomed everyone to the meeting and gave a special welcome to the Mayor of Corby. -

Policy Briefing for Emc Members

POLICY BRIEFING FORwww.emcouncils.gov.uk EMC MEMBERS 8 May 2015 The General and Local Elections 2015 What the General Election results mean for Local Government and Public Services in the East Midlands. East Midlands Councils in partnership with the Whitehall & Industry Group are holding an event for councillors and officers on Monday 22 June to explore the implications of today’s General Election results for local government in the East Midlands. Keynote speakers include Dr Jonathan Carr-West, Chief Executive of the LGIU Phillip Blond, Director of ResPublica Join in the conversation along with leaders in the public, private and voluntary sector working with or in local government. Further information is available here. The UK General and Local Elections were held on 7 May 2015. The General Election was fought across all 46 Parliamentary Constituencies in the region, with local elections held across the region’s unitary and district councils. East Midlands Councils has produced a summary of the General Election Results in the East Midlands here. Following the Conservatives gaining two seats from Labour in Corby (Tom Pursglove winning the seat from Andy Sawford) and Derby North (Amanda Solloway winning the seat from Chris Williamson) the Conservatives now hold 32 of the region’s seats and Labour hold 14. At the time of writing many of the local election results in the region were still awaited. The results known are: Boston – NOC no change; Derby – Labour hold; Lincoln – Labour hold; North West Leicestershire – Conservative hold. EMC will publish a summary of the full local election results in the region on its website next week. -

Annual Conference Edinburgh 2013: Stronger, Together

the Co-operative Party Annual Conference Edinburgh 2013: Stronger, together Annual report 2012 Hilton Grosvenor, Edinburgh Friday 4th October - Sunday 6th October #CoopParty Also available at www.party.coop Contents Chair’s Report 3 Local Government 18 Electoral Success 18 Organisation 4 Local government results in Co-operative National Executive Committee 4 Parliamentary seats 19 The Party Staff in 2012 5 Co-operative Councils’ Network 19 The Co-operative Party: London Mayoral and Assembly elections 19 A review of the highlights of the year 6 Highlights of Policy, 2012 Month-By-Month Highlights 11 Publications & Campaigns 20 National Politics 13 Party Support 22 Westminster 13 Party Support Website and handbook 22 Scotland 15 Summerfest & Weekend Schools 22 Wales 16 Listening Exercise 22 The Co-operative Party’s Plans for 2013 23 This annual report has been produced by the Co-operative Party Limited. Registered in England as an Industrial and Provident Society under the Industrial and Provident Societies Act 1965. Registered no. 30027R For information or more details, please contact: The Co-operative Party Limited Registered Office:77 Weston Street London SE1 3SD This document is available on our website. To receive an electronic version, please contact Dorota Kseba at [email protected] or telephone 020 7367 4155. t: 020 7367 4150 f: 020 7407 4476 e: [email protected] w: www.party.coop Chair’s Report 2012, the International Year of the Co-operative, was an exciting year for the movement that served to highlight how relevant we are, both in the UK and internationally. The Party was honoured to participate in the spectacular Co-operatives United in Manchester, which provided a wonderful opportunity to meet co-operators from all over the world. -

General Election 2015 Richard Keen Nambassa Nakatudde

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP7186, 28 July 2015 By Oliver Hawkins General Election 2015 Richard Keen Nambassa Nakatudde Inside: 1. Introduction 2. Countries and regions 3. Parties 4. Seats changing hands 5. Who voted for which party? 6. Candidates 7. Characteristics of those elected 8. The electorate, turnout and invalid votes 9. Safe and marginal seats 10. MPs who did not stand for re-election 11. Incumbent MPs who were defeated 12. New MPs 13. By-elections and changes of allegiance 2010-15 14. Polling day 15. Opinion polls 16. Constituencies www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Number CBP7186, 28 July 2015 Contents Summary 4 General Election 2015 seat winners map 5 General Election 2015 seat winners in equal sized constituencies 6 1. Introduction 7 2. Countries and regions 11 2.1 United Kingdom 11 2.2 Great Britain 12 2.3 England 13 2.4 Scotland 14 2.5 Wales 15 2.6 Northern Ireland 16 2.7 North East 17 2.8 North West 18 2.9 Yorkshire and the Humber 19 2.10 East Midlands 20 2.11 West Midlands 21 2.12 East of England 22 2.13 London 23 2.14 South East 24 2.15 South West 25 3. Parties 26 3.1 Conservative 26 3.2 Labour 28 3.3 Scottish National Party 30 3.4 Liberal Democrats 32 3.5 Plaid Cymru 34 3.6 United Kingdom Independence Party 36 3.7 Green Party 38 3.8 DUP and Sinn Féin 40 3.9 SDLP and UUP 41 4. -

The Role of Local Authorities in Health Issues

House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee The role of local authorities in health issues Eighth Report of Session 2012–13 Volume I: Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Additional written evidence is contained in Volume II, available on the Committee website at www.parliament.uk/clgcom Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 20 March 2013 HC 694 Published on 27 March 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £24.50 The Communities and Local Government Committee The Communities and Local Government Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Communities and Local Government. Current membership Mr Clive Betts MP (Labour, Sheffield South-East) (Chair) Bob Blackman MP (Conservative, Harrow East) Simon Danczuk MP Rochdale (Labour, Rochdale) Mrs Mary Glindon MP (Labour, North Tyneside) David Heyes MP (Labour, Ashton-under- Lyne) James Morris MP (Conservative, Halesowen and Rowley Regis) Mark Pawsey MP (Conservative, Rugby) John Pugh MP (Liberal Democrat, Southport) Andy Sawford MP (Labour, Corby) John Stevenson MP (Conservative, Carlisle) Heather Wheeler MP (Conservative, South Derbyshire) Heidi Alexander MP (Labour, Lewisham East), Bill Esterson MP (Labour, Sefton Central), Stephen Gilbert MP, (Liberal Democrat, St Austell and Newquay) and George Hollingbery (Conservative, Meon Valley) were also members of the Committee during this inquiry. Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. -

Living Former Members of the House of Commons

BRIEFING PAPER Number 05324, 7 January 2019 Living former Members Compiled by of the House of Sarah Priddy Commons Living former Members MPs are listed with any titles at the time they ceased to be an MP and the party they belonged to at the time. The list does not include MPs who now sit in the House of Lords. A list of members of the House of Lords who were Members of the House of Commons can be found on the Parliament website under House of Lords FAQs. Further information More detailed information on MPs who served between 1979 and 2010, including ministerial posts and party allegiance, covering their time in the UK Parliament and other legislatures, can be found in the Commons Library Briefing on Members 1979-2010. Association of Former Members of Parliament The PoliticsHome website has contact details for the Association of Former Members of Parliament. Parliament: facts and figures • Browse all briefings in the series This series of publications contains data on various subjects relating to Parliament and Government. Topics include legislation, MPs, select committees, debates, divisions and Parliamentary procedure. Feedback Any comments, corrections or suggestions for new lists should be sent to the Parliament and Constitution Centre. Suggestions for new lists welcomed. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Living former Members of the House of Commons Note: Does not include MPs who are now sit in the House of Lords Name Full Title Party* List Name Mr -

Parliamentary Debates House of Commons Official Report General Committees

PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT GENERAL COMMITTEES Public Bill Committee CHILDREN AND FAMILIES BILL Sixteenth Sitting Thursday 18 April 2013 (Afternoon) CONTENTS CLAUSES 72 and 73 agreed to. SCHEDULE 4, as amended, agreed to. CLAUSE 74 agreed to. CLAUSE 75 under consideration when the Committee adjourned till Tuesday 23 April at twenty-five minutes past Nine o’clock. PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS LONDON – THE STATIONERY OFFICE LIMITED £6·00 PBC (Bill 131) 2012 - 2013 Members who wish to have copies of the Official Report of Proceedings in General Committees sent to them are requested to give notice to that effect at the Vote Office. No proofs can be supplied. Corrigenda slips may be published with Bound Volume editions. Corrigenda that Members suggest should be clearly marked in a copy of the report—not telephoned—and must be received in the Editor’s Room, House of Commons, not later than Monday 22 April 2013 STRICT ADHERENCE TO THIS ARRANGEMENT WILL GREATLY FACILITATE THE PROMPT PUBLICATION OF THE BOUND VOLUMES OF PROCEEDINGS IN GENERAL COMMITTEES © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2013 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 615 Public Bill Committee18 APRIL 2013 Children and Families Bill 616 The Committee consisted of the following Members: Chairs: †MR CHRISTOPHER CHOPE,MR DAI HAVARD † Barwell, Gavin (Croydon Central) (Con) † Nokes, Caroline (Romsey and Southampton North) Brooke, -

CORBY and EAST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE SECOND BY-ELECTION POLL Lord Ashcroft October 2012

CORBY AND EAST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE SECOND BY-ELECTION POLL Lord Ashcroft October 2012 1,503 adults in the Corby and East Northamptonshire constituency were interviewed by telephone between 12 and 18 October 2012. Results have been weighted to be representative of all adults in the constituency. 1. As you may have heard, Louise Mensch, the MP for Corby and East Northamptonshire, is standing down and there wiLL therefore have to be a by-election in the next few months to elect a new MP for the area. Which candidate do you expect to vote for in the by-election? [Change since 2010 general election in brackets] Andy Sawford (Labour) 54% [+15%] Christine Emmett (Conservative) 32% [-10%] Jill Hope (Liberal Democrat) 5% [-10%] Margot Parker (UKIP) 6% Jonathan Hornett (Green Party) 1% Gordon Riddell (BNP) 1% [-4%] • This represents a 13-point swing from the Conservatives to Labour since the 2010 general election. • The Labour lead has widened from 15 to 22 points since the beginning of the campaign in August. 2. Are you fairLy sure that is what you wiLL do at the by-election, or do you think you may welL change your mind between now and then? [Change since August in brackets] ALL Lab Con Lib Dem Fairly sure that is how I will vote 86% [+3] 89% [+4] 87% [+2] 68% [+12] I may well change my mind 14% [-3] 15% [-4] 15% [-2] 32% [-12] 3. If you changed your mind, which party would you be most likely to switch to? ALL Lab Con Lib Dem Labour 17% - 39% 19% Conservative 22% 30% - 32% Liberal Democrat 17% 29% 16% - UKIP 13% 6% 22% 11% Green 3% 3% - 15% BNP 1% 1% - 0% Other 0% 0% 0% 0% Don’t know 26% 31% 23% 23% Lord Ashcroft Corby & East Northamptonshire poll 2 4.