Entrepreneuring As Performance: Understanding Entrepreneurship As a Process of Becoming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nightshiftmag.Co.Uk @Nightshiftmag Nightshiftmag Nightshiftmag.Co.Uk Free Every Month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 299 September Oxford’S Music Magazine 2021

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 299 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2021 Gig, Interrupted Meet the the artists born in lockdown finally coming to a venue near you! Also in this comeback issue: Gigs are back - what now for Oxford music? THE AUGUST LIST return Introducing JODY & THE JERMS What’s my line? - jobs in local music NEWS HELLO EVERYONE, Festival, The O2 Academy, The and welcome to back to the world Bullingdon, Truck Store and Fyrefly of Nightshift. photography. The amount raised You all know what’s been from thousands of people means the happening in the world, so there’s magazine is back and secure for at not much point going over it all least the next couple of years. again but fair to say live music, and So we can get to what we love grassroots live music in particular, most: championing new Oxford has been hit particularly hard by the artists, challenging them to be the Covid pandemic. Gigs were among best they can be, encouraging more the first things to be shut down people to support live music in the back in March 2020 and they’ve city and beyond and making sure been among the very last things to you know exactly what’s going be allowed back, while the festival on where and when with the most WHILE THE COVID PANDEMIC had a widespread impact on circuit has been decimated over the comprehensive local gig guide Oxford’s live music scene, it’s biggest casualty is The Wheatsheaf, last two summers. -

Seventh Annual Report

Scottish Institute for Policing Research Annual Report 2013 Cover picture © Police Scotland © Scottish Institute for Policing Research, April 2014 2 The Scottish Institute for Policing Research A 60 Second Briefing The Scottish Institute for Policing Research (SIPR) is a strategic collaboration between 12 of Scotland’s universities1 and the Scottish police service supported by investment from Police Scotland, the Scottish Funding Council and the participating universities. Our key aims are: • To undertake high quality, independent, and relevant research; • To support knowledge exchange between researchers and practitioners and improve the research evidence base for policing policy and practice; • To expand and develop the research capacity in Scotland’s universities and the police service; • To promote the development of national and international links with researcher, practitioner and policy communities. We are an interdisciplinary Institute which brings together researchers from the social sciences, natural sciences and humanities around three broad thematic areas: Police-Community Relations; Evidence & Investigation; and Police Organization; We promote a collaborative approach to research that involves academics and practitioners working together in the creation, sharing and application of knowledge about policing; Our activities are coordinated by an Executive Committee comprising academic researchers and chief police officers, and we are accountable to a Board of Governance which includes the Principals of the participating universities -

Tayside and Central Scotland Transport Partnership

2 TAYSIDE AND CENTRAL SCOTLAND TRANSPORT PARTNERSHIP Minute of the Meeting of the Tayside and Central Scotland Transport Partnership held in the Balmoral Suite, Queens Hotel, Leonard Street, Perth on Tuesday 23 June 2009 at 10.30am. Present: Councillor John Whyte (Angus Council); Councillors Dave Bowes, Will Dawson and Brian Gordon (Dundee City Council); Councillors, Ann Gaunt, John Kellas and Alan Jack (Perth and Kinross Council); Councillors Andrew Simpson and Jim Thomson (Stirling Council); Bill Wright, Gavin Roser and Douglas Fleming (Members). In Attendance: E Guthrie (Director); N Gardiner, M Cairns and M Scott (TACTRAN); G Taylor (Secretary); J Symon (Treasurer); I Cochrane (Angus Council); M Galloway and N Gellatly (Dundee City Council); L Goodfellow (Stirling Council); L Brown and A Deans (Perth and Kinross Council). Apologies for absence were received from Professor Malcolm Horner and Professor Tony Wells (Members); and Councillor Iain Gaul (Angus Council Member). Deputy Chair Jack, Presiding for Item 1 1. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST In terms of the Code of Conduct, Councillor Will Dawson declared a non- financial interest in Item 8, the Travel Plan Strategy and Action Plan Progress Report and Councillor Ann Gaunt declared a non-financial interest in Item 10, the Tay Estuary Rail Study Report. 2. APPOINTMENT OF CHAIRPERSON Gillian Taylor, Secretary to the Partnership, reported on the need to appoint a new Chairperson following the amendment to Dundee City Council’s nominated elected Member representation on the Partnership. Councillor John Whyte, seconded by Gavin Roser, proposed Councillor Alan Jack for the appointment of Chairperson. Thereafter a further nomination was received for Councillor Will Dawson which was proposed by Councillor Dave Bowes and seconded by Councillor John Kellas. -

University of Dundee Funeral Poverty in Dundee Bickerton, Ruth; Morelli

University of Dundee Funeral Poverty in Dundee Bickerton, Ruth; Morelli, Carlo DOI: 10.20933/100001153 Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Bickerton, R., & Morelli, C. (2019). Funeral Poverty in Dundee: Funeral Link Evaluation. University of Dundee. https://doi.org/10.20933/100001153 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Funeral Poverty in Dundee Funeral Link Evaluation Ruth Bickerton and Carlo Morelli University of Dundee Final Report July 2019 Project Reference Number SIF-R3-S2-LUPS-017 Lead Applicant Dundee City Council Project Title Tackling Funeral Poverty in Dundee through Social Enterprise Table of Contents -

• Principals Off Er Alternative to Loans Scheme

IRlBOT RICE GRLLERY a. BRQ~ University of Edinburgh, Old College THE South Bridge, Edinburgh EH8 9YL Tel: 031-667 1011 ext 4308 STATIONERS 24 Feb-24 March WE'RE BETTER FRANCES WALKER Tiree Works Tues·Sat 10 am·5 pm Admission Free Subsidised by the Scottish Ans Council Glasgow Herald Studen_t' Newspaper of the l'. ear thursday, february 15, 12 substance: JUNO A.ND •20 page supplement, THE PAYCOCK: Lloyd Cole interview .Civil War tragedy . VALENTINES at the .and compe~tion insi~ P.13 Lyceum p.10 Graduate Tax proposed • Principals offer alternative to loans scheme by Mark Campanile Means tested parental con He said that the CVCP administrative arrangements for Mr MacGregor also stated that tributions would be abolished, accepted that, in principle, stu loans and is making good prog administrative costs would be pro ress." hibitive, although the CVCP UNIVERSITY VICE Chan and the money borrowed would dents should pay something be repayed through income tax or towards their own education, but "The department will of course claim their plan would be cheaper cellors ancf Principals have national insurance contributions. that they believed that the current . be meeting the representatives of to implement than the combined announced details of a A spokesman for the CVCP, loans proposals were unfair, the universities, polytechnics, and running costs for grants and loans. graduate tax scheme which · Dr Ted Neild, told Student that administratively complicated, and colleges in due course to discuss NUS President Maeve Sher-. they want the government to the proposals meant that flawed because they still involved their role in certifying student lock has denounced the new prop consider as an alternative to graduates who had an income at a parental contributions, which are eligibility for loans." osals as "loans by any other student loans. -

Song of the Year

General Field Page 1 of 15 Category 3 - Song Of The Year 015. AMAZING 031. AYO TECHNOLOGY Category 3 Seal, songwriter (Seal) N. Hills, Curtis Jackson, Timothy Song Of The Year 016. AMBITIONS Mosley & Justin Timberlake, A Songwriter(s) Award. A song is eligible if it was Rudy Roopchan, songwriter songwriters (50 Cent Featuring Justin first released or if it first achieved prominence (Sunchasers) Timberlake & Timbaland) during the Eligibility Year. (Artist names appear in parentheses.) Singles or Tracks only. 017. AMERICAN ANTHEM 032. BABY Angie Stone & Charles Tatum, 001. THE ACTRESS Gene Scheer, songwriter (Norah Jones) songwriters; Curtis Mayfield & K. Tiffany Petrossi, songwriter (Tiffany 018. AMNESIA Norton, songwriters (Angie Stone Petrossi) Brian Lapin, Mozella & Shelly Peiken, Featuring Betty Wright) 002. AFTER HOURS songwriters (Mozella) Dennis Bell, Julia Garrison, Kim 019. AND THE RAIN 033. BACK IN JUNE José Promis, songwriter (José Promis) Outerbridge & Victor Sanchez, Buck Aaron Thomas & Gary Wayne songwriters (Infinite Embrace Zaiontz, songwriters (Jokers Wild 034. BACK IN YOUR HEAD Featuring Casey Benjamin) Band) Sara Quin & Tegan Quin, songwriters (Tegan And Sara) 003. AFTER YOU 020. ANDUHYAUN Dick Wagner, songwriter (Wensday) Jimmy Lee Young, songwriter (Jimmy 035. BARTENDER Akon Thiam & T-Pain, songwriters 004. AGAIN & AGAIN Lee Young) (T-Pain Featuring Akon) Inara George & Greg Kurstin, 021. ANGEL songwriters (The Bird And The Bee) Chris Cartier, songwriter (Chris 036. BE GOOD OR BE GONE Fionn Regan, songwriter (Fionn 005. AIN'T NO TIME Cartier) Regan) Grace Potter, songwriter (Grace Potter 022. ANGEL & The Nocturnals) Chaka Khan & James Q. Wright, 037. BE GOOD TO ME Kara DioGuardi, Niclas Molinder & 006. -

Sidney's Vomit Bug Spreads

Friday February 27th 2009 e Independent Cambridge Student Newspaper since 1947 Issue no 692 | varsity.co.uk »p9 Comment »Centrefold Special pull-out »p17 Arts Orwell’s The Dial: exclusive four-page Patrick Wolf: a overrated preview issue inside very odd man Sidney’s vomit ZING TSJENG bug spreads Students warned as other Colleges hit by norovirus Caedmon Tunstall-Behens open. Following a closure as punishment for non-Sidney students vomiting in the e outbreak of a vomiting bug in Sid- toilets, one bar worker commented, “ is ney Sussex has spread to other colleges, week it’s been the Sidney-ites themselves the University has con rmed. who have been having vomit problems, Although the University declined to albeit of quite a di erent nature.” say which Colleges have been a ected, e viral infection induces projectile Varsity understands that cases have also vomiting, fever, nausea, fever and diar- been reported at Queens’, Clare, Newn- rhoea. It can be incubated for 48 hours ham and Homerton. before its symptoms becoming appar- A spokesman said: “ ere are a few ent, and ends 48 hours a er the last isolated cases in other Colleges. It has vomit or bout. been con rmed that most of the indi- Transmission occurs through contact viduals a ected had had contact with with contaminated surfaces, body-to- Sidney people over the last few days.” body contact, orally or from inhalation e news comes a er Sidney was in of infected particles. lockdown for over a week with just over Sidney called in the city council’s en- 80 students, Fellows and catering sta vironmental health o cers at noon last debilitated by a suspected outbreak of Friday. -

Deacon Blue Fellow Hoodlums Mp3, Flac, Wma

Deacon Blue Fellow Hoodlums mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock / Pop Album: Fellow Hoodlums Country: Spain Released: 1991 Style: Blues Rock, Pop Rock, Synth-pop, Indie Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1899 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1729 mb WMA version RAR size: 1484 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 609 Other Formats: VOC MP2 AUD XM ASF WAV DXD Tracklist 1 James Joyce Soles 3:52 2 Fellow Hoodlums 3:22 3 Your Swaying Arms 4:13 4 Cover From The Sky 3:36 5 The Day That Jackie Jumped The Jail 3:44 6 The Wildness 5:48 7 A Brighter Star Than You Will Shine 4:37 8 Twist And Shout 3:37 9 Closing Time 6:12 10 Goodnight Jamsie 1:48 11 I Will See You Tomorrow 3:23 12 One Day I'll Go Walking 5:03 Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Sony Music Entertainment (UK) Ltd. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Sony Music Entertainment (UK) Ltd. Mastered At – DADC Austria Distributed By – Sony Music Credits Mixed By – Michael H. Brauer Producer – Jon Kelly Notes ©1991 Sony Music Entertainment (UK) Ltd. ℗1991 Sony Music Entertainment (UK) Ltd. Disc label: Made in Austria This Spanish issue has the extra text: Distribuido por Sony Music, Castellana 93, 28046 Madrid - and code 42-468550-10 at the bottom of the reverse/tray insert. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5099746855024 Rights Society: MCPS BIEM STEMRA Label Code: LC 0162 Other (Part No: Disc And Booklet): 01-468550-10 Other (Part No: Tray Insert): 42-468550-10 Matrix / Runout (Variant 1): 01-468550-10 21 A6 MASTERED BY DADC AUSTRIA Matrix / Runout (Variant 2): 01-468550-10 21 A5 MASTERED BY DADC -

Appendix-3-YMI-Case Studies

Appendix 3 YMI Case Studies Appendix 3A South Lanarkshire, Practical Music Making (Formula Fund) Appendix 3B Stirling, Traditional Music (Formula Fund) Appendix 3C Renfrewshire, Hear My Music (Formula Fund) Appendix 3D South Ayrshire, The Big Sing! (Formula Fund) Appendix 3E Fife, Ukelele in the Classroom (Formula Fund) Appendix 3F Shetland Programme (Formula Fund) Appendix 3G Hazelwood Music All (Informal Fund) Appendix 3H Makin a Brew (Informal Fund) Appendix 3I Software Training, iCreate (Informal Fund) Appendix 3J Drake Music Scotland, Developing Potential (Informal Fund) Appendix 3K Wee Studios (Informal Fund) Appendix 3L National Piping Centre (Informal Fund) Appendix 3A: South Lanarkshire, Practical Music Making (Formula Fund) About this case study This case study was developed as part of Creative Scotland’s evaluation of the YMI (YMI) in 2015/16. YMI is a national programme which is designed to create access to high quality music making opportunities for young people up to 25 years of age, particularly those that would not normally have the chance to participate. This is part of a series of 12 case studies which demonstrate some of the approaches used by YMI funded organisations, and highlight the impacts of this work. This case study is about Practical Music Making in the Classroom in South Lanarkshire. It was developed through discussions with eight pupils, one YMI practitioner, one primary teacher, four parents/carers, and the YMI project lead from South Lanarkshire Council. About Practical Music Making in the Classroom Practical Music Making in the Classroom is delivered to Primary 5 pupils in South Lanarkshire and ensures that the local authority meets the P6 target. -

Meet Author Alan Bissett Sporting Achievements the Stirling Fund

2012 alumni, staff and friends Meet author alan Bissett The 2011 Glenfiddich SpiriT of ScoTland wriTer of The year sporting achieveMents our STirlinG SporTS ScholarS the stirling Fund we Say Thank you 8 12 16 4 NEWS HIGHLIGHTS Successes and key developments 8 ALAN BISSETT Putting words on paper and on screen 12 HAZEL IRVINE An Olympic career 14 SPORT at STIRLING contents Thirty years of success 16 RESEARCH ROUND UP Stirling's contribution 38 18 MEET THE PRINCIPAL An interview with Professor Gerry McCormac 20 THE LOST GENERatiON? Graduate employment prospects 22 GOING WILD IN THE ARCHIVES Exhibition on campus 22 24 A CELEBRatiON OF cOLOUR AND SPRING Book launches at the University 25 THE STIRLING FUND Donations and developments 29 29 ADOPT A BOOK Support our campaign 31 CLASS NOTES 43 Find your friends 37 A WORD FROM THE PRESIDENT Your chance to get involved 38 MAKING THEIR MARK Graduates tell their story 43 WHERE ARE THEY NOW? Senior concierges in the halls 45 EVENTS FOR YOUR DIARY Let us entertain you 2 / stirling minds / Alumni, staff and Friends reasons to keep 10 in touch With over 44,000 Stirling alumni in 151 countries around the world there welcome are many reasons why you should keep in touch: Welcome to the 2012 edition of Stirling Minds which provides a glimpse into what has been an exciting 1. Maintain lifelong friendships. year for the University – from the presentation of 2. Network. Connection with the new Strategic Plan in the Scottish Parliament last alumni in similar fields, September to the ranking in a new THE (under 50 positions and locations. -

Hallett Arendt Rajar Topline Results - Wave 3 2019/Last Published Data

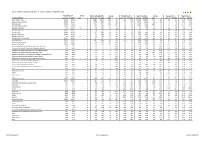

HALLETT ARENDT RAJAR TOPLINE RESULTS - WAVE 3 2019/LAST PUBLISHED DATA Population 15+ Change Weekly Reach 000's Change Weekly Reach % Total Hours 000's Change Average Hours Market Share STATION/GROUP Last Pub W3 2019 000's % Last Pub W3 2019 000's % Last Pub W3 2019 Last Pub W3 2019 000's % Last Pub W3 2019 Last Pub W3 2019 Bauer Radio - Total 55032 55032 0 0% 18083 18371 288 2% 33% 33% 156216 158995 2779 2% 8.6 8.7 15.3% 15.9% Absolute Radio Network 55032 55032 0 0% 4743 4921 178 4% 9% 9% 35474 35522 48 0% 7.5 7.2 3.5% 3.6% Absolute Radio 55032 55032 0 0% 2151 2447 296 14% 4% 4% 16402 17626 1224 7% 7.6 7.2 1.6% 1.8% Absolute Radio (London) 12260 12260 0 0% 729 821 92 13% 6% 7% 4279 4370 91 2% 5.9 5.3 2.1% 2.2% Absolute Radio 60s n/p 55032 n/a n/a n/p 125 n/a n/a n/p *% n/p 298 n/a n/a n/p 2.4 n/p *% Absolute Radio 70s 55032 55032 0 0% 206 208 2 1% *% *% 699 712 13 2% 3.4 3.4 0.1% 0.1% Absolute 80s 55032 55032 0 0% 1779 1824 45 3% 3% 3% 9294 9435 141 2% 5.2 5.2 0.9% 1.0% Absolute Radio 90s 55032 55032 0 0% 907 856 -51 -6% 2% 2% 4008 3661 -347 -9% 4.4 4.3 0.4% 0.4% Absolute Radio 00s n/p 55032 n/a n/a n/p 209 n/a n/a n/p *% n/p 540 n/a n/a n/p 2.6 n/p 0.1% Absolute Radio Classic Rock 55032 55032 0 0% 741 721 -20 -3% 1% 1% 3438 3703 265 8% 4.6 5.1 0.3% 0.4% Hits Radio Brand 55032 55032 0 0% 6491 6684 193 3% 12% 12% 53184 54489 1305 2% 8.2 8.2 5.2% 5.5% Greatest Hits Network 55032 55032 0 0% 1103 1209 106 10% 2% 2% 8070 8435 365 5% 7.3 7.0 0.8% 0.8% Greatest Hits Radio 55032 55032 0 0% 715 818 103 14% 1% 1% 5281 5870 589 11% 7.4 7.2 0.5% -

Mark Summers Sunblock Sunburst Sundance

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 11 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. SUNFREAKZ Belgian male producer (Tim Janssens) MARK SUMMERS 28 Jul 07 Counting Down The Days (Sunfreakz featuring Andrea Britton) 37 3 British male producer and record label executive. Formerly half of JT Playaz, he also had a hit a Souvlaki and recorded under numerous other pseudonyms Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 3 26 Jan 91 Summers Magic 27 6 SUNKIDS FEATURING CHANCE 15 Feb 97 Inferno (Souvlaki) 24 3 13 Nov 99 Rescue Me 50 2 08 Aug 98 My Time (Souvlaki) 63 1 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 2 Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 10 SUNNY SUNBLOCK 30 Mar 74 Doctor's Orders 7 10 21 Jan 06 I'll Be Ready 4 11 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 10 20 May 06 The First Time (Sunblock featuring Robin Beck) 9 9 28 Apr 07 Baby Baby (Sunblock featuring Sandy) 16 6 SUNSCREEM Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 26 29 Feb 92 Pressure 60 2 18 Jul 92 Love U More 23 6 SUNBURST See Matt Darey 17 Oct 92 Perfect Motion 18 5 09 Jan 93 Broken English 13 5 SUNDANCE 27 Mar 93 Pressure US 19 5 08 Nov 97 Sundance 33 2 A remake of "Pressure" 10 Jan 98 Welcome To The Future (Shimmon & Woolfson) 69 1 02 Sep 95 When 47 2 03 Oct 98 Sundance '98 37 2 18 Nov 95 Exodus 40 2 27 Feb 99 The Living Dream 56 1 20 Jan 96 White Skies 25 3 05 Feb 00 Won't Let This Feeling Go 40 2 23 Mar 96 Secrets 36 2 Total Hits : 5 Total Weeks : 8 06 Sep 97 Catch Me (I'm Falling) 55 1 20 Oct 01 Pleaase Save Me (Sunscreem