Rebirth Control in Tibetan Buddhism: Anything New? – Petr Jandáček

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JACEK TRZEBUNIAK* Analysis of Development of the Tibetan Tulku

The Polish Journal of the Arts and Culture Nr 10 (2/2014) / ARTICLE JACEK TRZEBUNIAK* (Uniwersytet Jagielloński) Analysis of Development of the Tibetan Tulku System in Western Culture ABSTRACT With the development of Tibetan Buddhism in Europe and America, from the second half of the twentieth century, the phenomenon of recognising a person as a reincarnation of Bud- dhist teachers appeared in this part of the world. Tibetan masters expected that the identified person will serve important social and religious functions for Buddhist communities. How- ever, after several decades since the first recognitions, the Western tulkus do not play the same important role in the development of Buddhism, as tulkus in China, and the Tibetan communities in exile. The article analyses the cultural and social causes of the different functioning of tulku institution in Western societies. The article shows that a different un- derstanding of identity, power and hierarchy mean that tulkus do not play significant roles in the development of Buddhism in this part of the world. KEY WORDS religious studies, Tibetan Buddhism, tulku, West INTRODUCTION Tulku (Tib. sprul sku) is a person in Tibetan Buddhism tradition who is recog- nised as a reincarnation of a famous Buddhist master. The tradition originated in the 13th century in the Kagyu (Tib. bka’ brgyud) sect when students of the Dusum Khyenpa (Tib. dus gsum mkhyen pa), after his death, found a boy and * Wydział Filozoficzny, Katedra Porównawczych Studiów Cywilizacji Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie, Polska e-mail: [email protected] 116 Jacek Trzebuniak recognised him as a reincarnation of their master1. -

Chenrezig Practice

1 Chenrezig Practice Collected Notes Bodhi Path Natural Bridge, VA February 2013 These notes are meant for private use only. They cannot be reproduced, distributed or posted on electronic support without prior explicit authorization. Version 1.00 ©Tsony 2013/02 2 About Chenrezig © Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche in Heart Treasure of the Enlightened One. ISBN-10: 0877734933 ISBN-13: 978-0877734932 In the Tibetan Buddhist pantheon of enlightened beings, Chenrezig is renowned as the embodiment of the compassion of all the Buddhas, the Bodhisattva of Compassion. Avalokiteshvara is the earthly manifestation of the self born, eternal Buddha, Amitabha. He guards this world in the interval between the historical Sakyamuni Buddha, and the next Buddha of the Future Maitreya. Chenrezig made a a vow that he would not rest until he had liberated all the beings in all the realms of suffering. After working diligently at this task for a very long time, he looked out and realized the immense number of miserable beings yet to be saved. Seeing this, he became despondent and his head split into thousands of pieces. Amitabha Buddha put the pieces back together as a body with very many arms and many heads, so that Chenrezig could work with myriad beings all at the same time. Sometimes Chenrezig is visualized with eleven heads, and a thousand arms fanned out around him. Chenrezig may be the most popular of all Buddhist deities, except for Buddha himself -- he is beloved throughout the Buddhist world. He is known by different names in different lands: as Avalokiteshvara in the ancient Sanskrit language of India, as Kuan-yin in China, as Kannon in Japan. -

Recounting the Fifth Dalai Lama's Rebirth Lineage

Recounting the Fifth Dalai Lama’s Rebirth Lineage Nancy G. Lin1 (Vanderbilt University) Faced with something immensely large or unknown, of which we still do not know enough or of which we shall never know, the author proposes a list as a specimen, example, or indication, leaving the reader to imagine the rest. —Umberto Eco, The Infinity of Lists2 ncarnation lineages naming the past lives of eminent lamas have circulated since the twelfth century, that is, roughly I around the same time that the practice of identifying reincarnating Tibetan lamas, or tulkus (sprul sku), began.3 From the twelfth through eighteenth centuries it appears that incarnation or rebirth lineages (sku phreng, ’khrungs rabs, etc.) of eminent lamas rarely exceeded twenty members as presented in such sources as their auto/biographies, supplication prayers, and portraits; Dölpopa Sherab Gyeltsen (Dol po pa Shes rab rgyal mtshan, 1292–1361), one such exception, had thirty-two. Among other eminent lamas who traced their previous lives to the distant Indic past, the lineages of Nyangrel Nyima Özer (Nyang ral Nyi ma ’od zer, 1124–1192) had up 1 I thank the organizers and participants of the USF Symposium on The Tulku Institution in Tibetan Buddhism, where this paper originated, along with those of the Harvard Buddhist Studies Forum—especially José Cabezón, Jake Dalton, Michael Sheehy, and Nicole Willock for the feedback and resources they shared. I am further indebted to Tony K. Stewart, Anand Taneja, Bryan Lowe, Dianna Bell, and Rae Erin Dachille for comments on drafted materials. I thank the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange for their generous support during the final stages of revision. -

C:\Users\Kusala\Documents\2009 Buddhist Center Update

California Buddhist Centers / Updated August 2009 Source - www.Dharmanet.net Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery Address: 16201 Tomki Road, Redwood Valley, CA 95470 CA Tradition: Theravada Forest Sangha Affiliation: Amaravati Buddhist Monastery (UK) EMail: [email protected] Website: http://www.abhayagiri.org All One Dharma Address: 1440 Harvard Street, Quaker House Santa Monica CA 90404 Tradition: Non-Sectarian, Zen/Vipassana Affiliation: General Buddhism Phone: e-mail only EMail: [email protected] Website: http://www.allonedharma.org Spiritual Director: Group effort Teachers: Group lay people Notes and Events: American Buddhist Meditation Temple Address: 2580 Interlake Road, Bradley, CA 93426 CA Tradition: Theravada, Thai, Maha Nikaya Affiliation: Thai Bhikkhus Council of USA American Buddhist Seminary Temple at Sacramento Address: 423 Glide Avenue, West Sacramento CA 95691 CA Tradition: Theravada EMail: [email protected] Website: http://www.middleway.net Teachers: Venerable T. Shantha, Venerable O.Pannasara Spiritual Director: Venerable (Bhante) Madawala Seelawimala Mahathera American Young Buddhist Association Address: 3456 Glenmark Drive, Hacienda Heights, CA 91745 CA Tradition: Mahayana, Humanistic Buddhism Contact: Vice-secretary General: Ven. Hui-Chuang Amida Society Address: 5918 Cloverly Avenue, Temple City, CA 91780 CA Tradition: Mahayana, Pure Land Buddhism EMail: [email protected] Spiritual Director: Ven. Master Chin Kung Amitabha Buddhist Discussion Group of Monterey Address: CA Tradition: Mahayana, Pure Land Buddhism Affiliation: Bodhi Monastery Phone: (831) 372-7243 EMail: [email protected] Spiritual Director: Ven. Master Chin Chieh Contact: Chang, Ei-Wen Amitabha Buddhist Society of U.S.A. Address: 650 S. Bernardo Avenue, Sunnyvale, CA 94087 CA Tradition: Mahayana, Pure Land Buddhism EMail: [email protected] Spiritual Director: Ven. -

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts By Ramin Etesami A thesis submitted to the graduate school in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the International Buddhist College, Thailand March, 20 Abstract The Tulku institution is a unique characteristic of Tibetan Buddhism with a central role in this tradition, to the extent that it is present in almost every aspect of Tibet’s culture and tradition. However, despite this central role and the scope and diversity of the socio-religious aspects of the institution, only a few studies have so far been conducted to shed light on it. On the other hand, an aura of sacredness; distorted pictures projected by the media and film industries;political propaganda and misinformation; and tendencies to follow a pattern of cult behavior; have made the Tulku institution a highly controversial topic for research; and consequently, an objective study of the institution based on a critical approach is difficult. The current research is an attempt to comprehensively examine different dimensions of the Tulku tradition with an emphasis on the issue of its orthodoxy with respect to the core doctrines of Buddhism and the social implications of the practice. In this research, extreme caution has been practiced to firstly, avoid any kind of bias rooted in faith and belief; and secondly, to follow a scientific methodology in reviewing evidence and scriptures related to the research topic. Through a comprehensive study of historical accounts, core Buddhist texts and hagiographic literature, this study has found that while the basic Buddhist doctrines allow the possibility for a Buddhist teacher or an advanced practitioner to “return back to accomplish his tasks, the lack of any historical precedence which can be viewed as a typical example of the practice in early Buddhism makes the issue of its orthodoxy equivocal and relative. -

“Little Tibet” with “Little Mecca”: Religion, Ethnicity and Social Change on the Sino-Tibetan Borderland (China)

“LITTLE TIBET” WITH “LITTLE MECCA”: RELIGION, ETHNICITY AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE SINO-TIBETAN BORDERLAND (CHINA) A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Yinong Zhang August 2009 © 2009 Yinong Zhang “LITTLE TIBET” WITH “LITTLE MECCA”: RELIGION, ETHNICITY AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE SINO-TIBETAN BORDERLAND (CHINA) Yinong Zhang, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 This dissertation examines the complexity of religious and ethnic diversity in the context of contemporary China. Based on my two years of ethnographic fieldwork in Taktsang Lhamo (Ch: Langmusi) of southern Gansu province, I investigate the ethnic and religious revival since the Chinese political relaxation in the 1980s in two local communities: one is the salient Tibetan Buddhist revival represented by the rebuilding of the local monastery, the revitalization of religious and folk ceremonies, and the rising attention from the tourists; the other is the almost invisible Islamic revival among the Chinese Muslims (Hui) who have inhabited in this Tibetan land for centuries. Distinctive when compared to their Tibetan counterpart, the most noticeable phenomenon in the local Hui revival is a revitalization of Hui entrepreneurship, which is represented by the dominant Hui restaurants, shops, hotels, and bus lines. As I show in my dissertation both the Tibetan monastic ceremonies and Hui entrepreneurship are the intrinsic part of local ethnoreligious revival. Moreover these seemingly unrelated phenomena are in fact closely related and reflect the modern Chinese nation-building as well as the influences from an increasingly globalized and government directed Chinese market. -

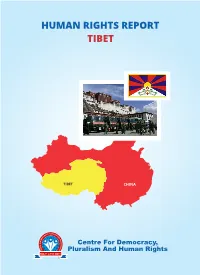

12 Inside Tibet Report.Cdr

HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT TIBET TIBET CHINA Centre For Democracy, Pluralism And Human Rights HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT TIBET Writer Nartam Vivekanand Motiram Editor Prerna Malhotra Nartam Vivekanand Motiram is working as an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Shyam Lal College, University of Delhi. His areas of interest include International Human Rights, International Political Theory, India’s Foreign Policy, and Tribal Life and Culture. Prerna Malhotra teaches English at Ram Lal Anand College, University of Delhi. She has co/authored six books, including the one on Delhi Riots 2020 and articles in journals of repute. She is currently pursuing a research project of ICSSR, Govt. of India on Maoism related issues. © CDPHR No part of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without giving due credit to the Centre for Democracy, Pluralism and Human Rights. About CDPHR Introduction Centre for Democracy, Pluralism and Human Rights (CDPHR) is an organisation broadly working in the area of human rights. Our motto is- equality, dignity and justice for every individual on this planet. We are committed to advocate upholding values of democracy and pluralism for a conducive environment for equality, dignity and justice. We endeavour to voice out human rights violations of individuals, groups and communities so as ultimately viable solutions maybe worked on. We dream of a world that accepts pluralistic ways of life, tradition and worship through democratic means and practices. Vision CDPHR envisions an equitable and inclusive society based on dignity, justice, liberty, freedom, trust, hope, peace, prosperity and adherence to law of land. We believe that multiple sections of societies are deprived of basic human rights and violation of their social, political, economic, religious and developmental rights is a sad reality. -

Tibetan Timeline

Information provided by James B. Robinson, associate professor, world religions, University of Northern Iowa Events (Tibetan Calendar Date) 17 Dec 1933 - Thirteenth Dalai Lama Passes Away in Lhasa at the age of 57 (Water-Bird Year, 10th month, 30th day) 6 July 1935 - Future 14th DL born in Taktser, Amdo, Tibet (Wood-Pig Year, 5th month, 5th day) 17 Nov 1950 - Assumes full temporal (political) power after China's invasion of Tibet in 1949 (Iron-Tiger Year, 10th month, 11th day) 23 May 1951 - 17-Point Agreement signed by Tibetan delegation in Peking under duress 1954 Confers 1st Kalachakra Initiation in Norbulingka Palace, Lhasa July 1954 to June 1955 - Visits China for peace talks, meets with Mao Zedong and other Chinese leaders, including Chou En-Lai and Deng Xiaoping 10 March 1959 - Tens of thousands of Tibetans gathered in front of Norbulingka Palace, Lhasa, to prevent His Holiness from going to a performance at the Chinese Army Camp in Lhasa. Tibetan People's Uprising begins in Lhasa March 1959 - Tibetan Government formally reestablished at Lhudup Dzong. 17-Point Agreement formally repudiated by Tibetan Government 17 March 1959 - DL escapes at night from Norbulingka Palace in Lhasa 30 March 1959 - Enters India from Tibet after a harrowing 14-day escape 1963 - Presents a draft democratic constitution for Tibet. First exile Tibetan Parliament (assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies) established in Dharamsala. 21 Sept 1987 - Delivers historic Five Point Peace Plan for Tibet in Washington, D.C. to members of the U.S. Congress 10 Dec 1989 - Awarded Nobel Prize for Peace in Oslo, Norway 1992 - Initiates a number of additional major democratic steps, including direct election of Kalons (Ministers) by the Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies and establishment of a judiciary branch. -

2008 UPRISING in TIBET: CHRONOLOGY and ANALYSIS © 2008, Department of Information and International Relations, CTA First Edition, 1000 Copies ISBN: 978-93-80091-15-0

2008 UPRISING IN TIBET CHRONOLOGY AND ANALYSIS CONTENTS (Full contents here) Foreword List of Abbreviations 2008 Tibet Uprising: A Chronology 2008 Tibet Uprising: An Analysis Introduction Facts and Figures State Response to the Protests Reaction of the International Community Reaction of the Chinese People Causes Behind 2008 Tibet Uprising: Flawed Tibet Policies? Political and Cultural Protests in Tibet: 1950-1996 Conclusion Appendices Maps Glossary of Counties in Tibet 2008 UPRISING IN TIBET CHRONOLOGY AND ANALYSIS UN, EU & Human Rights Desk Department of Information and International Relations Central Tibetan Administration Dharamsala - 176215, HP, INDIA 2010 2008 UPRISING IN TIBET: CHRONOLOGY AND ANALYSIS © 2008, Department of Information and International Relations, CTA First Edition, 1000 copies ISBN: 978-93-80091-15-0 Acknowledgements: Norzin Dolma Editorial Consultants Jane Perkins (Chronology section) JoAnn Dionne (Analysis section) Other Contributions (Chronology section) Gabrielle Lafitte, Rebecca Nowark, Kunsang Dorje, Tsomo, Dhela, Pela, Freeman, Josh, Jean Cover photo courtesy Agence France-Presse (AFP) Published by: UN, EU & Human Rights Desk Department of Information and International Relations (DIIR) Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) Gangchen Kyishong Dharamsala - 176215, HP, INDIA Phone: +91-1892-222457,222510 Fax: +91-1892-224957 Email: [email protected] Website: www.tibet.net; www.tibet.com Printed at: Narthang Press DIIR, CTA Gangchen Kyishong Dharamsala - 176215, HP, INDIA ... for those who lost their lives, for -

Nala Endowment Fund Annual Report 2017 About Nala Endowment Fund

NALA ENDOWMENT FUND ANNUAL REPORT 2017 ABOUT NALA ENDOWMENT FUND Inspired by the philosophical, cultural and spiritual heritage of Himala- yan countries, we strive to preserve the treasures of Eastern thought and art. We support both local and foreign projects focusing on care and ed- ucation for children from poor families or orphans, we help spreading knowledge and skills related to traditional Buddhist art, contribute to translations of precious texts into Western languages and also direct- ly support translators. We create conditions for meditation, study and practice of traditional Tibetan methods of healing. We support precious teachers who are the source of endless valuable knowledge and inspira- tion, and we care for their health and vitality. We believe that our activity will spread awareness of possibilities of hu- man development and beautiful objectives that timeless, thousands of years old Eastern teachings have, namely the full development of mind’s potential and lasting, unconditional happiness for oneself and others. OUR AIM AND MISSION The nances we not only raise but also actively create are used for the support of projects home and abroad. Traditionally we have been bringing possibilities of quality education for children from poor families in Nepal, who found their home and a big family in the supported monasteries. We continue in this support and believe that it is especially education and kind approach that can best prepare these young men and women for life and increase their chances of a happy future. However, our aim is also to bring possibilities of inner development which leads to psychological stability and happiness to people in the West, where it is so important to stress basic human values. -

The Dalai Lama

THE INSTITUTION OF THE DALAI LAMA 1 THE DALAI LAMAS 1st Dalai Lama: Gendun Drub 8th Dalai Lama: Jampel Gyatso b. 1391 – d. 1474 b. 1758 – d. 1804 Enthroned: 1762 f. Gonpo Dorje – m. Jomo Namkyi f. Sonam Dargye - m. Phuntsok Wangmo Birth Place: Sakya, Tsang, Tibet Birth Place: Lhari Gang, Tsang 2nd Dalai Lama: Gendun Gyatso 9th Dalai Lama: Lungtok Gyatso b. 1476 – d. 1542 b. 1805 – d. 1815 Enthroned: 1487 Enthroned: 1810 f. Kunga Gyaltsen - m. Kunga Palmo f. Tenzin Choekyong Birth Place: Tsang Tanak, Tibet m. Dhondup Dolma Birth Place: Dan Chokhor, Kham 3rd Dalai Lama: Sonam Gyatso b. 1543 – d. 1588 10th Dalai Lama: Tsultrim Gyatso Enthroned: 1546 b. 1816 – d. 1837 f. Namgyal Drakpa – m. Pelzom Bhuti Enthroned: 1822 Birth Place: Tolung, Central Tibet f. Lobsang Drakpa – m. Namgyal Bhuti Birth Place: Lithang, Kham 4th Dalai Lama: Yonten Gyatso b. 1589 – d. 1617 11th Dalai Lama: Khedrub Gyatso Enthroned: 1601 b. 1838– d. 1855 f. Sumbur Secen Cugukur Enthroned 1842 m. Bighcogh Bikiji f. Tseten Dhondup – m. Yungdrung Bhuti Birth Place: Mongolia Birth Place: Gathar, Kham 5th Dalai Lama: 12th Dalai Lama: Trinley Gyatso Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso b. 1856 – d. 1875 b. 1617 – d. 1682 Enthroned: 1860 Enthroned: 1638 f. Phuntsok Tsewang – m. Tsering Yudon f. Dudul Rapten – m. Kunga Lhadze Birth Place: Lhoka Birth Place: Lhoka, Central Tibet 13th Dalai Lama: Thupten Gyatso 6th Dalai Lama: Tseyang Gyatso b. 1876 – d. 1933 b. 1683 – d. 1706 Enthroned: 1879 Enthroned: 1697 f. Kunga Rinchen – m. Lobsang Dolma f. Tashi Tenzin – m. Tsewang Lhamo Birth Place: Langdun, Central Tibet Birth Place: Mon Tawang, India 14th Dalai Lama: Tenzin Gyatso 7th Dalai Lama: Kalsang Gyatso b. -

Discovering BUDDHISM at Home

Discovering BUDDHISM at Home Awakening the limitless potential of your mind, achieving all peace and happiness SUBJECT AREA 7 Refuge in the Three Jewels Readings 7. Refuge in the Three Jewels 1 Discovering BUDDHISM at Home Discovering BUDDHISM at Home 2 7. Refuge in the Three Jewels Contents Seeking an Inner Refuge, by His Holiness the Dalai Lama 4 Teachings on Refuge, by Lama Thubten Yeshe 9 Essential Buddhist Practice, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche 18 Refuge, by Lama Thubten Yeshe 41 Further required reading includes the following texts: The Wish-Fulfilling Golden Sun, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche (pp. 69–75) Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, 1997 gold edition (pp. 394–428) or 2006 blue edition (pp. 352-84) Taking Refuge in the Three Jewels, an FPMT Booklet This section of readings: © FPMT, Inc., 2001. All rights reserved. 7. Refuge in the Three Jewels 3 Discovering BUDDHISM at Home Seeking an Inner Refuge by H. H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama His Holiness the Dalai Lama is the spiritual and temporal leader of the Tibetan people. He came to India after the Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1959. Ever since then increasing numbers of non-Tibetans have been becoming aware of his enlightened and compassionate wisdom. In 1989 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his unwavering advocacy of non-violent resistance to the shockingly cruel and violent Chinese occupation of his homeland. Here is an extract of a teaching given in Delhi in the early 1960’s, translated into English for the first time. Discovering BUDDHISM at Home 4 7.