Haciric 11 Conference Proce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2019 B

Lorem ipsum Fondation Botnar | Annual Report 2019 B Annual Report 2019 Editorial Fondation Botnar | Annual Report 2019 03 2019 at Contents Fostering the best possible a glance future for young people Total funding awarded CHF 2019 at a glance 02 Among the key developments for Fondation m Botnar in 2019 were the appointment to 42.29 Editorial 03 the Board of Florian Schweitzer, a wide- ly respected figure in tech finance and a Grants awarded Milestones 2019 04 champion of young tech entrepreneurs, and the establishment of an Expert Advi- Message from the CEO 08 sory Group consisting of members of our 51 Cities fit for young people Board, Management Office, and experts 10 from academia, business, and NGOs with AI and digital for the next 14 expertise in our focus areas. This group, Funding according to grant type which replaces Fondation Botnar’s former generation Scientific Commission, has provided sub- Meaningful youth participation stantial support in examining and advising 16 us on funding applications to ensure we Perspectives: health data 18 make high-impact investments to improve young people’s health. governance Thomas A. Gutzwiller In addition, this past year saw the Man- Governance 20 I am a firm believer in the combined poten- agement Office fully staffed by experi- tial of digital solutions and thriving local enced team players with the networks and One-off grants: 13% Foundation team 21 ecosystems to foster the best possible know-how that Fondation Botnar needs to Implementation grants: 61% Financial statements 2019 22 future for young people around the world. implement its strategy in the areas of city Research grants: 26% It has therefore been an honour to be ap- engagement, AI and digital innovation, and Grants awarded 24 pointed the Chair of the Fondation Botnar meaningful youth participation. -

Frontal Lobe Deficits and Anger As Violence Risk Markers for Males with Major Mental Illness in a High Secure Hospital

Frontal Lobe deficits and Anger as violence risk markers for males with Major Mental Illness in a High Secure Hospital University of Lincoln Faculty of Health, Life and Social Sciences Doctorate in Clinical Psychology Doctorate in Clinical Psychology 2012 Anne-Marie O’Hanlon, MSc; BSc. Submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Clinical Psychology Acknowledgements Primary thanks are reserved for Dr Louise Braham owing to her guidance and supervision throughout this research project. Her support, dedication and enthusiasm towards this study provided on-going encouragement. Thanks are given to further staff members from the Trent Doctorate Course in Clinical Psychology for their feedback in relation to this research, particularly, Dr Mark Gresswell, Dr Roshan das Nair, Dr David Dawson, Dr Aidan Hart and Dr Nima Moghaddam. The staff team within the hospital’s Mental Health Directorate are also thanked. This includes Responsible Clinicians who assisted with recruitment, David Jones and his team for providing support and supervision during completion of the VRS assessments, as well as administrative and nursing staff, who made conduction of this study possible. Gratitude is further extended to John Flynn for providing support and advice with regard to data analysis. It is recognised that this study would not have been possible without advice and agreement from; the Hospital’s Clinical Director of Mental Health, the University of Lincoln Ethics Committee, Nottingham Research Management and Governance Committee, as -

Records Management Good Management Good Records

Records Management Good Management Good Records November 2011 Contents SECTION 1 FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Types of Records covered by GMGR ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Media of Records covered by GMGR .................................................................................................................................... 7 SECTION 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................... 9 General Context .................................................................................................................................................................. 10 Monitoring Records Management Performance ................................................................................................................ 12 Legal and Professional Obligations .................................................................................................................................... -

The President's Report

The President’s Report 2006 / 2007 The Hebrew University of Jerusalem The President’s Report 2006 2007 The President’s Contents 2 From the President Report 4 Humanities 18 Medical Sciences 30 New Faculty 34 Research Activities 36 Interdepartmental Equipment Units 38 Student Life 40 Physical Development 42 The Campaign 44 Financial Report 50 Officers of the University 50 Board of Governors 52 Benefactors 54 Campaign Gifts 58 Major Gifts 2 From the President FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Governor As in the past few years, the Hebrew University covers an extensive range of human cultures and continues to face financial uncertainty, government genres of human creativity within the broadest budget cuts and indecisive policy on higher education. geographic parameters. We need to create a new This year however, the government realized that the paradigm for the humanities that emphasizes the situation cannot continue and appointed a blue-ribbon discourse between cultures, genres and periods while committee under the chairmanship of former finance preserving the classical scholarship in which we excel. minister Avraham “Baiga” Shochat. We therefore formed an international committee The committee was charged with conducting a headed by Professor John Gager of Princeton University, thorough review of key aspects of higher education whose recommendations to restructure the Faculty, its in Israel: government funding, student tuition curricula and academic and administrative structure (complemented by student support), services for are in the process of being implemented. We are students, the division of labor between universities also considering ways to adapt both the physical and colleges, employment models for faculty and academic infrastructure of the Faculty to this members and support for research. -

Broadmoor Hospital

Broadmoor Hospital Broadmoor Hospital is a high-security psychiatric hos- for infanticide, on 27 May 1863. Notes described her as pital at Crowthorne in the Borough of Bracknell Forest being 'feeble minded'; it has been suggested by an anal- in Berkshire, England. It is the best known of the three ysis of notes that she was most likely also suffering from high-security psychiatric hospitals in England, the other congenital syphilis. The first male patients arrived on 27 two being Ashworth and Rampton. Scotland has a sim- February 1864. The original building plan of five blocks ilar institution at Carstairs, officially known as the State for men and one for women was completed in 1868. A Hospital but often called Carstairs Hospital, which serves further male block was built in 1902. Scotland and Northern Ireland. Due to overcrowding at Broadmoor, a branch asylum was The Broadmoor complex houses about 210 patients, all constructed at Rampton Secure Hospital and opened in of whom are men since the female service closed with 1912. Rampton was closed as a branch asylum at the end most of the women moving to a new service in Southall of 1919 and reopened as an institution for mental defec- in September 2007, a few moving to the national high tives rather than lunatics. During World War I Broad- secure service for women at Rampton and a few else- moor’s block 1 was also used as a prisoner-of-war camp, where. At any one time there are also approximately 36 called Crowthorne War Hospital, for mentally ill German patients on trial leave at other units. -

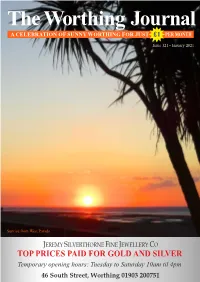

Jan-2021-Email

The Worthing Journal A CELEBRATION OF SUNNY WORTHING FOR JUST £1 PER MONTH Issue 121 - January 2021 Sunrise from West Parade JEREMY SILVERTHORNE FINE JEWELLERY CO TOP PRICES PAID FOR GOLD AND SILVER Temporary opening hours: Tuesday to Saturday 10am til 4pm 46 South Street, Worthing 01903 200751 2 The Worthing Journal is YOUR COMMUNITY MAGAZINE delivered direct to homes in Worthing, Ferring, Findon, A NEW Year dawns, with all the £40,000 since the appeal was first Lancing and Sompting. fresh hopes and aspirations that launched in 2002. Any assistance It can also be bought from entails. Especially after such a would be greatly appreciated. selected newsagents, cafés, pubs shocking 2020! The Journal is delivered to and community centres. The Journal would like to take doorsteps by a company of this opportunity to thank volunteer pavement pounders. To subscribe for the year, please everybody who subscribed or Editor Paul Holden cannot thank send a cheque, postal order or resubscribed in the run up to them enough, for they are out in cash (£11) to The Worthing Christmas. all weathers ensuring the Journal at 91 Alinora Crescent, If you’ve not yet persuaded magazine arrives each month. Goring, Worthing, BN12 4HH. family or friends to sign up, If you would like to volunteer (it’s There is also a paypal facility at please give them a nudge and tell great exercise, and you discover www.worthingjournal.co.uk them it’s never too late. places you never knew existed) To advertise, please email The Journal launches its annual please contact Holden via the [email protected] or seafront flag appeal on page 88. -

Independent Inquiry Into the Care and Treatment of Peter Bryan Part One

Independent Inquiry into the Care and Treatment of Peter Bryan Part One A report for NHS London September 2009 Panel members Jane Mishcon was appointed as Chair of the Inquiry. She is a barrister at Hailsham Chambers whose main area of practice is clinical negligence. She has chaired nine inquiries following homicides committed by psychiatric patients. The other Panel members appointed were: Dr Tim Exworthy, a consultant forensic psychiatrist at Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust. Stuart Wix is a forensic nurse consultant at Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Foundation Trust. Mike Lindsey is a former deputy director of social services at Shropshire County Council. Professor Tom Sensky, a Professor of Psychological Medicine and a consultant psychiatrist, provided expert advice to the Panel. 2 Acknowledgements The co-ordination of this Inquiry was undertaken by Derek Mechen of Verita to whom we are indebted for his indefatigable support. His inordinate patience and efficiency made our difficult and lengthy task that much easier and his sensitive handling of the investigation progress benefited all concerned. He really was the „backbone‟ of this Inquiry. We also could not have done without the rest of the Verita team who provide an excellent service to Inquiries generally. We are also grateful to the wonderful team from the Fiona Shipley Transcribing Service for their unflagging efforts in recording and transcribing the evidence for us. They endured long and tiring hours with efficient good humour. We are grateful for the frank and open way in which the witnesses gave their evidence to us. Although some of the key personalities had already had to give evidence to the internal inquiry panel which investigated and reported shortly after the homicide of Brian Cherry, for most of the witnesses this was the first time that they had been questioned in any way about their involvement with Peter Bryan or (where applicable) their managerial responsibilities within the various services involved with him. -

Biographical Portraits

BRITAIN & JAPAN: BIOGRAPHICAL PORTRAITS VOLUME VI Sir Winston Churchill saying goodbye to Crown Prince Akihito, the present Emperor of Japan, after lunch at No 10 Downing Street on 30 April 1953. (See Ch. 1) Courtesy Mainichi. BRITAIN & JAPAN: Biographical Portraits VOLUME VI Compiled & Edited by HUGH CORTAZZI JAPAN SOCIETY PAPERBACK EDITION Not for resale BRITAIN & JAPAN: BIOGRAPHICAL PORTRAITS Volume VI Compiled & Edited by Hugh Cortazzi First published in 2007 by GLOBAL ORIENTAL LTD PO Box 219 Folkestone Kent CT20 2WP UK www.globaloriental.co.uk © The Japan Society 2007 ISBN 978-1-905246-33-5 [Case] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library SPECIAL THANKS The Chairman and Council of the Japan Society together with the Editor and Publishers of this volume wish to express their thanks to the following organizations for their support: The Daiwa Anglo- Japanese Foundation, The Great Britain-Sasakawa Foundation. Set in Bembo 11 on 11.5pt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester Printed and bound in England by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wilts Table of Contents Introduction by Hugh Cortazzi xi Alphabetical List of Contributors xv Index of Biographical -

Annual Report 2019 B

Lorem ipsum Fondation Botnar | Annual Report 2019 B Annual Report 2019 Editorial Fondation Botnar | Annual Report 2019 03 2019 at Contents Fostering the best possible a glance future for young people Total funding awarded CHF 2019 at a glance 02 Among the key developments for Fondation m Botnar in 2019 were the appointment to 42.29 Editorial 03 the Board of Florian Schweitzer, a wide- ly respected figure in tech finance and a Grants awarded Milestones 2019 04 champion of young tech entrepreneurs, and the establishment of an Expert Advi- Message from the CEO 08 sory Group consisting of members of our 51 Cities fit for young people Board, Management Office, and experts 10 from academia, business, and NGOs with AI and digital for the next 14 expertise in our focus areas. This group, Funding according to grant type which replaces Fondation Botnar’s former generation Scientific Commission, has provided sub- Meaningful youth participation stantial support in examining and advising 16 us on funding applications to ensure we Perspectives: health data 18 make high-impact investments to improve young people’s health. governance Thomas A. Gutzwiller In addition, this past year saw the Man- Governance 20 I am a firm believer in the combined poten- agement Office fully staffed by experi- tial of digital solutions and thriving local enced team players with the networks and One-off grants: 13% Foundation team 21 ecosystems to foster the best possible know-how that Fondation Botnar needs to Implementation grants: 61% Financial statements 2019 22 future for young people around the world. implement its strategy in the areas of city Research grants: 26% It has therefore been an honour to be ap- engagement, AI and digital innovation, and Grants awarded 24 pointed the Chair of the Fondation Botnar meaningful youth participation. -

2006 / 2005 Report S NETHERLANDS PHILIPPINES JORDAN ALGERIA UNITED KINGDOM ARGENTINA UZBEKISTAN ST

CZECH REPUBLIC THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY OF JERUSALEM: FOR THE WORLD INDIA LEBANON FIJI SEYCHELLES The President ITALY MADAGASCAR NEPAL MOZAMBIQUE IRAN SOUTH AFRICA ’ s Report 2005 / 2006 The Hebrew University of Jerusalem NETHERLANDS PHILIPPINES JORDAN ALGERIA UNITED KINGDOM ARGENTINA UZBEKISTAN ST. LUCIA CONGO AUSTRALIA SOUTH KOREA ISRAEL SWAZILAND BAHAMAS UNITED STATES OF AMERICA HUNGARY NIGERIA KYRGYZSTAN ZIMBABWE HAITI BARBADOS THE PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2005/2006 BELARUS ZAMBIA JAPAN ST. KITTS ETHIOPIA BOSNIA HERZEGOVINA NICARAGUA PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY GEORGIA BOLIVIA TIBET RUSSIA BRAZIL CHILE SOMALIA BULGARIA THAILAND MONGOLIA COLOMBIA RWANDA CHINA MOROCCO MALAWI ARMENIA TURKEY GHANA COSTA RICA KAZAKHSTAN CAMEROON SURINAME ECUADOR CYPRUS BURKINA FASO CONTENTS 2 From the President 4 For the World 36 New Investments 40 Research Activities 42 Student Life 44 Physical Development 46 The Campaign 48 Financial Report 54 Officers of the University 54 Board of Governors 56 Benefactors 58 Campaign Gifts 62 Major Gifts A NOBEL FOR JERUSALEM PROFESSOR ROBERT J. AUMANN WINS NOBEL PRIZE IN ECONOMICS THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY OF JERUSALEM: FOR THE WORLD NAME OF THE GAME The awarding of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences to Professor Robert J. Aumann in 2005 was a momentous event for the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the State of Israel, and marked international recognition both of Prof. Aumann’s achievements and of the Hebrew University as a world-class institution of higher learning. Prof. Aumann, a member of the University’s Center for the Study of Rationality and professor emeritus at the Einstein Institute of Mathematics, was awarded the Nobel Prize for his insightful work in laying the foundation for game theory analysis of long-run relationships.