The Journal of the Fell & Rock Climbing Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Getting to the Isle of Arran Getting Around the Isle of Arran Familiarisation with the Isle of Arran A Geology Classroom A Turbulent History Land Ownership and Access Island Plants Accommodation on the Isle of Arran Food and Drink on the Isle of Arran The Maps The Walks Tourist Information Emergency Services on the Isle of Arran THE WALKS Walk 1 Goat Fell and Brodick Walk 2 Brodick Castle and Country Park Walk 3 Brodick and the Clauchland Hills Walk 4 Sheeans and Glen Cloy Walk 5 Lamlash and the Clauchland Hills Walk 6 Sheeans and The Ross Walk 7 Lamlash to Brodick Walk 8 Holy Isle from Lamlash Walk 9 Tighvein and Monamore Glen Walk 10 Tighvein and Urie Loch Walk 11 Glenashdale Falls Walk 12 Glenashdale and Loch na Leirg Walk 13 Lamlash and Kingscross Walk 14 Lagg to Kildonan Coastal Walk Walk 15 Kilmory Forest Circuit Walk 16 Sliddery and Cnocan Donn Walk 17 Tighvein and Glenscorrodale Walk 18 The Ross and Cnoc a' Chapuill Walk 19 Shiskine and Clauchan Glen Walk 20 Ballymichael and Ard Bheinn Walk 21 The String and Beinn Bhreac Walk 22 Blackwaterfoot and King's Cave Walk 23 Machrie Moor Stone Circles Walk 24 Dougarie and Beinn Nuis Walk 25 Dougarie and Sail Chalmadale Walk 26 Circuit of Glen Iorsa Walk 27 Imachar and Beinn Bharrain Walk 28 Pirnmill and Beinn Bharrain Walk 29 Coire Fhion Lochain Walk 30 Catacol and Meall nan Damh Walk 31 Catacol and Beinn Bhreac Walk 32 Catacol and Beinn Tarsuinn Walk 33 Lochranza and Meall Mòr Walk 34 Gleann Easan Biorach Walk 35 Lochranza and Cock of Arran Walk 36 Lochranza and Sail an Im Walk 37 Sannox and Fionn Bhealach Walk 38 North Glen Sannox Horseshoe Walk 39 Glen Sannox Horseshoe Walk 40 Glen Sannox to Glen Rosa Walk 41 Corrie and Goat Fell Walk 42 Glen Rosa and Beinn Tarsuinn Walk 43 Western Glen Rosa Walk 44 Eastern Glen Rosa Appendix 1 The Arran Coastal Way Appendix 2 Gaelic/English Glossary Appendix 3 Useful Contact Information . -

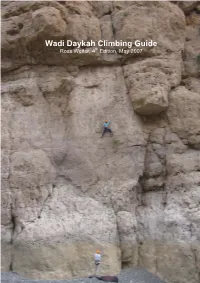

Wadi Daykah Climbing Guide Ross Weiter, 4Th Edition, May 2007

Wadi Daykah Climbing Guide Ross Weiter, 4th Edition, May 2007 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Wadi Daykah Guide, May 2007 Page 1 of 11 Cover: Kim Vaughn and Bill Huguelet do the business on “Al Kirobi” (6a), photo: Ross Weiter A WARNING ABOUT ROCK CLIMBING Climbing is a sport where you may be seriously injured or killed. Read this before you use this guide. This guide is a compilation of often-unverified information gathered from many different climbers. The author(s) cannot assure the accuracy of any of the information in this guide, including the route descriptions and the difficulty ratings. These may be incorrect or misleading as it is impossible for any one author to climb all the routes and confirm all the information. Some routes listed in the guide have had only one ascent and the information has not been verified. Also, ratings are subjective and depend on the physical characteristics such as height, experience, technical ability, confidence and physical fitness of the climber who supplied the ratings. Therefore, be warned that you must exercise your own judgement with regard to the route location, description, difficulty and your ability to safely protect yourself from the risks of rock climbing. Examples of these risks are: falling due to technical difficulty or holds breaking off, falling rock, climbing equipment dropped by other climbers, equipment failure and failure of protection including fixed protection such as bolts. You should not depend on any information gleaned from this guide for your personal safety. Your safety depends on your own experience, equipment and climbing skill. If you have any doubt as to your ability to safely attempt any route described in this guide, do not attempt it. -

Modern Yosemite Climbing 219

MODERN YOSEMITE CLIMBING 219 MODERN YOSEMITE CLIMBING BY YVON CHOUINARD (Four illustrations: nos. 48-5r) • OSEMITE climbing is the least known and understood, yet one of the most important, schools of rock climbing in the world today. Its philosophies, equipment and techniques have been developed almost independently of the rest of the climbing world. In the short period of thirty years, it has achieved a standard of safety, difficulty and technique comparable to the best European schools. Climbers throughout the world have recently been expressing interest in Yosemit e and its climbs, although they know little about it. Until recently, even most American climbers were unaware of what was happening in their own country. Y osemite climbers in the past had rarely left the Valley to climb in other areas, and conversely few climbers from other regions ever come to Yosemite; also, very little has ever been published about this area. Climb after climb, each as important as a new climb done elsewhere, has gone completely unrecorded. One of the greatest rock climbs ever done, the 1961 ascent of the Salethe Wall, received four sentences in the American Alpine Journal. Just why is Y osemite climbing so different? Why does it have techniques, ethics and equipment all of its own ? The basic reason lies in the nature of the rock itself. Nowhere else in the world is the rock so exfoliated, so glacier-polished and so devoid of handholds. All of the climbing lines follow vertical crack systems. Nearly every piton crack, every handhold, is a vertical one. Special techniques and equipment have evolved through absolute necessity. -

What the New NPS Wilderness Climbing Policy Means for Climbers and Bolting Page 8

VERTICAL TIMES The National Publication of the Access Fund Summer 13/Volume 97 www.accessfund.org What the New NPS Wilderness Climbing Policy Means for Climbers and Bolting page 8 HOW TO PARK LIKE A CHAMP AND PRESERVE ACCESS 6 A NEW GEM IN THE RED 11 WISH FOR CLIMBING ACCESS THIS YEAR 13 AF Perspective “ The NPS recognizes that climbing is a legitimate and appropriate use of Wilderness.” — National Park Service Director Jonathan Jarvis his past May, National Park Service (NPS) Director Jonathan Jarvis issued an order explicitly stating that occasional fixed anchor use is T compatible with federally managed Wilderness. The order (Director’s Order #41) ensures that climbers will not face a nationwide ban on fixed anchors in NPS managed Wilderness, though such anchors should be rare and may require local authorization for placement or replacement. This is great news for anyone who climbs in Yosemite, Zion, Joshua Tree, Canyonlands, or Old Rag in the Shenandoah, to name a few. We have always said that without some provision for At the time, it seemed that fixed anchors, technical roped climbing can’t occur — and the NPS agrees. the tides were against us, The Access Fund has been working on this issue for decades, since even before we officially incorporated in 1991. In 1998, the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) that a complete ban on fixed issued a ban on fixed anchors in Wilderness (see photo inset) — at the time, it anchors in all Wilderness seemed that the tides were against us, that a complete ban on fixed anchors in all Wilderness areas was imminent. -

Forestry Shelves Link-Road Plans Conkers! U-Turn on Road Will Force Rethink for Arran's Harvest Strategy

30th October 2008 / The Arran Voice Ltd Tel: 01770 303 636 E-mail: [email protected] 30th October 2008 — 082 65p Forestry shelves link-road plans CONKERS! U-turn on road will force rethink for Arran's harvest strategy After harvesting of forests like those around Meall Buidhe, the Forestry will have to deal with Arran's more remote western plantations DUE TO HIGH costs and environmental timber haulage route which would link concerns, the Forestry Commission the String Road and the Ross Road has opted to postpone plans to but we've decided to shelve it for the develop a road connecting Shedog and moment,' a forestry spokesman told The Glenscorrodale forests. The route was Arran Voice earlier this week. 'A thorough suggested as part of major strategy to assessment of the route showed it would harvest the large stock of mature timber be prohibitively expensive,' he added. now mounting on the island. Designed The proposed link between Shedog as a way of relieving some of the and Kilpatrick via Beinn Tarsuinn — pressure on both the Ross and the String planned to avert the need to shuttle roads, it would have diverted harvested timber lorries on the Ross Road — has timber from forest areas in the west also been shelved. It was estimated (Shedog and Kilpatrick) directly down that the construction of the forestry the Monamore Glen into Lamlash and roads would cost in excess of £700,000 then north to the Brodick loading slip and the Forestry was keen to benefit on Market Road. from £317,000 from the government’s Strategic Timber Transport Fund. -

Chance to Question the High Heid Yins Continued from Front Page

23rd October 2008 / The Arran Voice Ltd Tel: 01770 303 636 E-mail: [email protected] 23rd October 2008 — 081 65p Chance to WHAT’S GOING ON IN question LAMLASHPhotos by Howard Wood BAY? the high heid yins HOW OFTEN DO we hear it said on Arran that ‘the authorities’ never consult us or listen to what we think? That is all set to change on Friday 7th November at the Ormidale Sports Pavilion, 7.30pm. Leading people from both local and national government have agreed to answer whatever posers islanders fire at them, in Arran’s own Question Time, complete with TV cameras. Katy Clark MP and Kenneth Gibson MSP will both be there, as will David O’Neill, leader of North Ayrshire Council. John Michel of the NAC Planning department initially promised THE RESEARCH VESSEL Alba na Mara has spent to come, but there will be an the last week surveying Lamlash Bay and surrounding equally weighty representative areas of the Clyde. The vessel was launched in February if he is unable to make it. David 2008 and handed over to the Scottish Fisheries McIndoe, director of Housing Research Service in April. It has a crew of eight plus Development for Trust Housing, accommodation for up to five scientists using the latest promises to attend. He represents state-of-the-art equipment. For more information the parent organisation of which on the Research Vessel check out: http://www.frs- Arran Homes is part, and has said scotland.gov.uk/FRS.Web/Uploads/Documents/ he will bring at least one other OR10Albaweb2.pdf expert in the field. -

Wilderness Rock Climbing Indicators

WILDERNESS ROCK CLIMBING INDICATORS AND CLIMBING MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS IN THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE by Katherine Y. McHugh A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Geography, Applied Geospatial Sciences Northern Arizona University December 2019 Approved: Franklin Vernon, Ph.D., chair Mark Maciha, Ed.D. Erik Murdock, Ph.D. H. Randy Gimblett, Ph.D. ABSTRACT WILDERNESS ROCK CLIMBING INDICATORS AND CLIMBING MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS IN THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE KATHERINE Y. MCHUGH This pilot study addresses the need to characterize monitoring indicators for wilderness climbing in the National Park Service (NPS) as which are important to monitoring efforts as components in climbing management programs per Director’s Order #41, Section 7.2 Climbing. This research adopts a utilitarian conceptual framework suited to applied management objectives. Critically, it advances analytical connections between science and management through an integrative review of the resources informing park planning; including law and policy, climbing management documents, academic research on climbing management, recreation ecology, and interagency wilderness character monitoring strategies. Monitoring indicators include biophysical, social, and administrative topics related to climbing and are conceptually structured based on the interagency wilderness character monitoring model. The wilderness climbing indicators require both field and administrative monitoring; field monitoring of the indicators should be implemented by climbing staff and skilled volunteers as part of a patrol program, and administrative indicators mirror administrative wilderness character monitoring methods that can be carried out by a park’s wilderness coordinator or committee. Indicators, monitoring design, and recommended measures were pilot tested in two locations: Grand Canyon and Joshua Tree National Parks. -

LVIA Environmental Statement RES

LVIA Environmental Statement RES turbines of 131-150 m, and as was agreed with SNH. The location of the Study Area is shown 4. Landscape and Visual Assessment on Figure 4.1. Introduction 4.8 A zone of theoretical visibility (ZTV) map was generated, illustrating areas from where the proposed wind turbines may be visible in the Study Area. The ZTV was based on bare earth 4.1 This chapter considers the potential effects of the Proposal on: topography and therefore does not take account of potential screening by vegetation or buildings. The ZTV is used as tool for understanding where significant visual effects may Landscape as a resource in its own right (caused by changes to the constituent elements • occur. Receptors which are outside the ZTV would not be affected by the turbines of the of the landscape, its specific aesthetic or perceptual qualities and the character of the Proposal and are not considered further in this landscape and visual impact assessment landscape); and (LVIA). The ZTV to tip height (149.9 m) is shown on Figure 4.1, and the ZTV to hub height • Views and visual amenity as experienced by people (caused by changes in the (100 m) is shown on Figure 4.2. appearance of the landscape). Effects Assessed 4.2 Landscape and visual assessments are therefore distinct, but interconnected, processes. This chapter describes landscape and visual effects separately. Within each section, the 4.9 The following effects have been assessed in accordance with the principles contained within cumulative effects of the Proposal in the context of other proposed and consented wind the Guidelines for Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment, 3rd Edition1 (hereafter referred farms in the area are also considered, as potential future cumulative effects. -

2016 Tacoma Mountaineers Intermediate Climbing Manual

TACOMA MOUNTAINEERS Intermediate Climbing Manual 2016 Table of Contents Welcome to the Tacoma Mountaineers _______________________________________________________________________ 3 Course Information _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 5 Course Description _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 5 2016 Intermediate Course Roster _______________________________________________________________________________ 7 Course Policies and Requirements _____________________________________________________________________________ 11 General Notes __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Late for Lecture / Absenteeism Policy _______________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Conservation Requirement ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Winter Overnight Requirement ______________________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Basic Climbing Field Trip Teaching Requirement __________________________________________________________________________ 12 Mentor Program ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ 13 Rope Leader, Climb Leader, & Graduation Policies __________________________________________________________ 15 Rope Lead Process ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Asset Register

Property NAC Ref Street Name Street Locality Town Area Post UPRN Eastin Northi Ward Use Number Code g ng 10 Central Avenue G2000031 10 Central Avenue Ardrossan Ayrshire KA22 7DX 000126010550 223527 643252 Ardrossan and Commercial, Shop Arran Unit 11 Glasgow Street G2004398 11 Glasgow Street Ardrossan Ayrshire KA22 8EP 000126008595 222932 642145 Ardrossan and NAC Offices, Admin.- Arran Other 12 Princes Street T1918951 12 Princes Street Ardrossan Ayrshire KA22 8BP 000126056773 222902 642092 Ardrossan and Office Arran 14 Central Avenue G2000058 14 Central Avenue Ardrossan Ayrshire KA22 7DX 000126010552 223528 643259 Ardrossan and Commercial, Shop Arran Unit 16 Hill Street G2001216 16 Hill Street Ardrossan Ayrshire 000126009063 223043 642202 Ardrossan and Transport, Car Park Arran 2 Aitken Place T1907216 2 Ardrossan Team Aitken Place Ardrossan Ayrshire KA22 8PR 000126060283 223374 643012 Ardrossan and NAC Offices, Office Arran General Office 3 Towns Growers G2232811 3 Towns Growers Park View Ardrossan Ayrshire 000126087370 223836 643024 Ardrossan and Ground, Amenity Arran Land/Flower Bed 32 Montgomerie G2001518 32 Montgomerie Street Ardrossan Ayrshire 000126060213 223014 642429 Ardrossan and Industrial & Street Arran Storage, Covered Store 32 Montgomerie G2001631 32 Montgomerie Street Ardrossan Ayrshire KA22 8HW 000126010061 222987 642404 Ardrossan and Other Education, Street Arran Community/Public Hall 37 Rowanside G2001690 37 Rowanside Terrace Ardrossan Ayrshire KA22 7LN 000126011338 223128 643683 Ardrossan and Commercial, Shop Terrace Arran -

Climbing Management Plan/ Finding of No Significant Impact

FINAL CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN/ FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT February 1995 Devils Tower National Monument Crook County, Wyoming U.S. Dc:nartment of the Interior National Park Service Rocky Mountain Region Final Climbing Management/ Finding of No Significant Impact Devils Tower National Monument Crook County, Wyoming This Final Climbing Management Plan (FCMP)/Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) for Devils Tower National Monument sets a new direction for man_ aging climbing activity at the tower for the next three to five years. Its purpose is to protect the natural and cultural resources of Devils Tower and to provide for visitor enjoyment and appreciation of this unique feature. The tower will be managed as a significant natural and cultural resource. The National Park Service will manage Devils Tower as primarily a crack climbing site in such a way that will be more compatible with the butte's geology, soils, vegetation, nesting raptors, visual appearance, and natural quiet. Recreational climbing at Devils Tower will be managed in relation to the tower's significance as a culturat resource. No new bolts or fixed pitons will be permitted on the tower, though replacement of existing bolts and fixed pitons will be allowed. In this way, the NPS intends that there be.no new physical impacts to Devils Tower. In respect for the reverence many American Indians hold for Devils Tower as a sacred site, rock climbers will be asked to voluntarily refrain from climbing on Devils Tower during the culturally significant month of June. The monument's staff will begin interpreting the cultural significance of Devils Tower for all visitors along with the more traditional themes of natural history and rock climbing. -

The Northwest Passage

THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE A guidebook to the rockclimbs of Q'emiln Park Post Falls, Idaho* With information on climbing traditions, natural history and environmental preservation. Ah, for just one time I would take the Northwest Passage To find the hand of Franklin reaching for the Beauford Sea; Tracing one warm line through a land so wide and savage And make a Northwest Passage to the sea. Stan Rogers Text and Topos - Rusty Baillie Photography, and rigging - Richard LeFrancis Computer layout design - Maxine Whiteside *This PDF has been reproduced from copies of the original pamphlets prepared by Rusty, Richard and Maxine. This is a work in progress, and the Post Falls Parks Department hopes to fill in some gaps, update, and further refine the text over time. Please let us know how we can make this publication a better resource for the climbing community! Updated 9/23/14 Climbing buddies Richard LeFrancis, left, and Rusty Baillie stand above the popular climbing walls at Q’emiln Park. The two have improved climbing and hiking in Post Falls. It took three or four full days to shape up each climbing route. Safety: While every effort has been made to keep this guide as accurate as possible, there can be no guarantee that all the information will be, or will remain, reliable. Leading in particular, especially with natural protection, involves significant risks. Sport climbs, though bolt protected, can include significant runouts, with the attendant risk of serious injury. Your primary trust should be in your own sound, conservative judgment. When in doubt - toprope! Your use of this rockclimbing guidebook indicates that you fully understand these risks and that you are assuming responsibility for your own safety.