ABSTRACT Title of Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

With Papal Encyclicals As Background, Sessions Discuss Industrial

The Pittsburg Catholic " XpsfdöP «¿^O — oí the Diocese of Pittsburgh—Founded in 1844— tWO DOLLARS PKB YKAi PITTSBURGH, PA., THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 1942 'a 33 SINGLE COPY FIVE CENTS 98th YEAR—No. 51 Committee Named Report Says All Catholic Monasteries in Germany In Citizens' Clean Now Closed By Nazis With Papal Encyclicals as Background, Reading Campaign Lisbon, Feb. 16, (NC)—-Reports reaching here from Germany say that all Catholic monasteries have Sessions Discuss Industrial Problems Will List Offensive Magazines For Information of Mayor ; now been closed by the Nazi gov- ernment. It was known that many Other Moves Planned previously had been invaded and Catholic Refugee Progress Toward Social Justice, seized, but the present report in- Following the suggestion made dicates that the remainder have Adjustments for War Conditions by Mayor Cornelius D. Scully at a now suffered the same fate. From Nazis Will meeting held in the Chamber of At the famous Benedictine mon- And Afterward Are Studied Here Commerce rooms last w.eek by a astery of Beuron, Abbot Benedict Speak Here Mar. 2 citizens' committee supporting the Bauer, O.S.B., was seized and put Clean Literature Campaign origin- in a home ostensibly for aged men. Discussion, against the background of the Papal Engelicals, ated by the Federation of Catholic The Abbot is actually in thorough Dr. Solzbacher, Victim of War, Persecution, Former Youth of the progress toward social justice achieved in recent years High School Students, Rev. Cyril vigor, as will be known to many in the conduct of industry, of the adjustments that must be J. -

Reverend Joseph D. Karabin

Reverend Joseph D. Karabin Biographical Information YEAR OF BIRTH: 1947 YEAR OF DEATH: N/A ORDINATION: May 4, 1974 Employment/Assignment History 1974 - 1979 Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Midland, PA 1979 - 1980 St. Joan of Arc, Library, PA 1980 St. Joseph the Worker, New Castle, PA 1980 - 1981 Holy Name, Duquesne, PA 1981 - 1986 St. Albert the Great, Baldwin, PA 1986 - 2002 Braddock Hospital, Braddock , PA Summary In March 1980, the Diocese of Pittsburgh received a report from a victim who was sexually abused by Father Joseph D. Karabin while Karabin was assigned to St. Joan of Arc. Bishop Vincent Leonard then sent a letter to the House of Affirmation, a treatment center, notifying them that Karabin would arrive on March 25, 1980 for an evaluation with respect to the "incident" which Leonard advised he did not want to describe in the letter. Karabin was returned to active ministry after he completed treatment. In March, 1985, Father Raymond Froelich, Pastor of St. Albert the Great where Karabin was assigned as Parochial Vicar, notified Bishop Bevilacqua of another child whom Father Karabin had sexually abused. On March 7, 1985, two memorandums by Bishop Bosco documented a meeting held between himself and Karabin in with respect to the new report. Bosco advised Karabin that he would have to be reassigned due to the complaint. Karabin agreed, but "did not seem happy" with the possibility that his reassignment may not be immediate due to this being a "recurrence of a previous problem." According to Karabin, this "latest incident" was caused by stress he was under from not having his own pastorate. -

Volume 24 Supplement

2 GATHERED FRAGMENTS Leo Clement Andrew Arkfeld, S.V.D. Born: Feb. 4, 1912 in Butte, NE (Diocese of Omaha) A Publication of The Catholic Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania Joined the Society of the Divine Word (S.V.D.): Feb. 2, 1932 Educated: Sacred Heart Preparatory Seminary/College, Girard, Erie County, PA: 1935-1937 Vol. XXIV Supplement Professed vows as a Member of the Society of the Divine Word: Sept. 8, 1938 (first) and Sept. 8, 1942 (final) Ordained a priest of the Society of the Divine Word: Aug. 15, 1943 by Bishop William O’Brien in Holy Spirit Chapel, St. Mary Seminary, Techny, IL THE CATHOLIC BISHOPS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA Appointed Vicar Apostolic of Central New Guinea/Titular Bishop of Bucellus: July 8, 1948 by John C. Bates, Esq. Ordained bishop: Nov. 30, 1948 by Samuel Cardinal Stritch in Holy Spirit Chapel, St. Mary Seminary Techny, IL The biographical information for each of the 143 prelates, and 4 others, that were referenced in the main journal Known as “The Flying Bishop of New Guinea” appears both in this separate Supplement to Volume XXIV of Gathered Fragments and on the website of The Cath- Title changed to Vicar Apostolic of Wewak, Papua New Guinea (PNG): May 15, 1952 olic Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania — www.catholichistorywpa.org. Attended the Second Vatican Council, Sessions One through Four: 1962-1965 Appointed first Bishop of Wewak, PNG: Nov. 15, 1966 Appointed Archbishop of Madang, PNG, and Apostolic Administrator of Wewak, PNG: Dec. 19, 1975 Installed: March 24, 1976 in Holy Spirit Cathedral, Madang Richard Henry Ackerman, C.S.Sp. -

HISTORY of the NATIONAL CATHOLIC COMMITTEE for GIRL SCOUTS and CAMP FIRE by Virginia Reed

Revised 3/11/2019 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC COMMITTEE FOR GIRL SCOUTS AND CAMP FIRE By Virginia Reed The present National Catholic Committee for Girl Scouts and Camp Fire dates back to the early days of the Catholic Youth Organization (CYO) and the National Catholic Welfare Conference. Although it has functioned in various capacities and under several different names, this committee's purpose has remained the same: to minister to the Catholic girls in Girl Scouts (at first) and Camp Fire (since 1973). Beginnings The relationship between Girl Scouting and Catholic youth ministry is the result of the foresight of Juliette Gordon Low. Soon after founding the Girl Scout movement in 1912, Low traveled to Baltimore to meet James Cardinal Gibbons and consult with him about her project. Five years later, Joseph Patrick Cardinal Hayes of New York appointed a representative to the Girl Scout National Board of Directors. The cardinal wanted to determine whether the Girl Scout program, which was so fine in theory, was equally sound in practice. Satisfied on this point, His Eminence publicly declared the program suitable for Catholic girls. In due course, the four U.S. Cardinals and the U.S. Catholic hierarchy followed suit. In the early 1920's, Girl Scout troops were formed in parochial schools and Catholic women eagerly became leaders in the program. When CYO was established in the early 1930's, Girl Scouting became its ally as a separate cooperative enterprise. In 1936, sociologist Father Edward Roberts Moore of Catholic charities, Archdiocese of New York, studied and approved the Girl Scout program because it was fitting for girls to beome "participating citizens in a modern, social democracy." This support further enhanced the relationship between the Catholic church and Girl Scouting. -

History of St. Valentine Faith Community

History of St. Valentine Faith Community “The new church is the visible symbol of the fulfillment of many years of patient labors and countless sacrifices on the part of the priests, religious and people who have seen the territory of their parish develop from a tired mining district into an inviting area where thousands of families take pride in their community.” These were the words of Bishop John J. Wright, who dedicated the present Catholic Church of St. Valentine in Bethel Park, Pennsylvania, in 1967. Now in the golden jubilee year of 1981, the priests, religious and people of St. Valentine’s Church are able to look back with gratitude on a full half century of development and fulfillment. As they begin their second half century, they rededicate themselves to a life with Christ in the fellowship of their families and the community in which they continue to take pride. How Saint Valentine’s Began In the summer of 1923 Father Gerold, Pastor of St. Ann’s Church in Castle Shannon, began giving catechism instructions to children of Catholic parents in the little mining community of Coverdale. A few months later, Father Gerold obtained permission from Bishop Hugh C. Boyle to celebrate Holy Mass for approximately 70 Catholic families employed at Mine No. 8 of the Pittsburgh Terminal Coal. Co. That Mass, in a company-owned home which still stands today on South Park Road near Church Road, was the beginning of St. Valentine’s Parish. It was not until two years later that Father Gerold could buy a plot of ground at the corner of West Library Avenue and Ohio Street as the site for a church. -

Class Notes Spring04.4

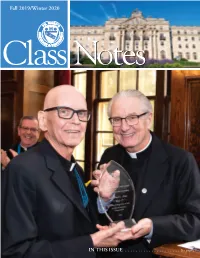

Fall 2019/Winter 2020 Class NNootteess IN THIS ISSUE . See page 27 Faculty News (left to right – first row) Fr. Phillip J. Brown, P.S.S., Most Rev. William E. Lori, Fr. Gladstone Stevens, P.S.S. (left to right – second row) Dr. Michael J. Gorman (commencement speaker), Fr. Daniel Moore, P.S.S., Dr. Brent Laytham Fr. Phillip J. Brown, P.S.S. published the arti - Supreme Court Historical Society, the Board of Trustees of the cle: “Who Owns the Church” in a festschrift Thomas More Society of Maryland, and as Religious Assistant to for Rev. Robert Kaslyn, late Dean of the School the Society of Our Lady of the Most Holy Trinity. On a monthly of Canon Law of the Catholic University of basis Fr. Brown continues to serve as Chaplain to Teams of Our America. Fr. Brown represented St. Mary’s at Lady and continues to travel to dioceses for recruitment visits. the National Association of Catholic Theological Schools meeting in Chicago, On November 2, 2019, Fr. Dennis Billy, October 4-5, and the Annual Award Reception C.Ss.R. was a keynote speaker at the Diocese of the Catholic Mobilizing Network at the Apostolic Nunciature of Tucson, Arizona’s 6th Annual Men’s in Washington, DC, October 10. He attended the Annual Conference. The title of his presentation was, Awards Reception of St. Luke’s Institute at the Apostolic “Fully Alive! Living in the Wounds of the Nunciature in Washington, DC on October 21 and was invested Risen Lord—Our Growing Band of Brothers.” as Chaplain of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of On December 4, 2019 he delivered the 45th Jerusalem on October 26, 2019. -

The UN's Anti-Zionism Resolution: Christian Responses

The UN's Anti-Zionism Resolution: Christian Responses by Judith Hershcopf Banki THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE Institute of Human Relations 165 East 56 Street, New York, N.Y. 10022 J CONTENTS PREFACE. INTRODUCTION. ROMAN CATHOLIC RESPONSES... CATHOLIC PRESS COMMENTARY PROTESTANT, ORTHODOX AND EVANGELICAL REACTIONS.... REGIONAL AND LOCAL CHURCH ASSOCIATIONS........ PROTESTANT AND ORTHODOX PRESS COMMENTS........ ECUMENICAL AND INTERRELIGIOUS RESPONSES CAMPUS MINISTRIES. .'. OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES.. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS SUGGESTED READING. PREFACE The resolution proposed by radical Arab nations and their allies that sought to stigmatize Zionism as "a form of raicsm and racial discrimination" was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on November 10, 1975. This survey of Chris• tian responses to the UN's anti-Zionism resolution documents reactions from representative Christian leaders and institu• tions during the several months following the adoption of that declaration. Under normal circumstances, this study—even though it is the most comprehensive and well-documented of its kind would be regarded as an historic record of a past event, perhaps mainly of interest to interreligious historians. Unfortunately, the campaign to defame and discredit Zionism did not subside with that episode; it is a continuing effort, and more than likely augurs a pattern of future threats and challenges to the Jewish community. Later meetings of the UN Economic and Social Commission (May 1976) were the scene of vicious harangues intended to caricature -

Gathered Fragments Vol. VI No. 2

GATHERED FRAGMENTS Publication of The Catholic Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania Volume VI, Number 2 Fah/wmler 1993 enlarged in 1953, to provide accommodations for 10 nuns. At that tJ r:t time the total enrollment was 400 children taught by the Vincentian MONSIGNOR RUSSElL DUKER Sisters of Charity of Perrysville, PA The present rectory was built SPEAKING ON in 1931. The convent was sold in 1985 to Housing Opportunities, EAsTERN RITES Inc. oF 1HE CAmouc CHuRCH After serving the parish as pastor for 42 years, Fr. Duwell died on June 20, 1963. He was buried on the day on which he was to SYNOD HAll, OAKUND celebrate his Golden Jubilee of the Priesthood. SUNDAY, OCTOBER 8, 1995 On July 2, 1963, Fr. Michael A. Dravecky, pastor of Holy 2:30PM Trinity Church in Duquesne, PA, assumed his duties as pastor of Holy Trinity Church, McKeesport, PA, at the request of Bishop k:> q, John J. Wright. Msgr. Dravecky served the parish from 1963 to Editor's Comer May 30, 1974, when he was transferred to St. Barnabas Church, For this issue of Gathered Fragments, the Board of the Catholic Swissvale, P A where he served until 1982 when he retired. Historical Society decided to focus on parishes which would be With the transfer of Msgr. Dravecky, Bishop Vincent Leonard celebrating anniversaries this year. assigned Fr. Edward P. Bunchek as pastor. He served the parish, I wrote to these parishes asking for any history, significant fact, undertaking various projects and renewal plans with the assistance or vignette, that they could provide. -

Chimbote, Peru Catechetical Resource Manual

OUR Diocesan Mission Chimbote, Peru Catechetical Resource Manual Secretariat for Evangelization and Catholic Education DIOCESE OF PITTSBURGH OUR Diocesan Mission Chimbote, Peru Catechetical Resource Manual Secretariat for Evangelization and Catholic Education DIOCESE OF PITTSBURGH Copyright ©2015 Roman Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh CATECHETICAL RESOURCE MANUAL Pittsburgh Diocesan Mission in Chimbote TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Welcome to Chimbote a. Introduction, Michel Therrien, S.T.L., S.T.D., Secretary for Evangelization and Catholic Education b. Personal Message to our Teachers and Students in Catholic Schools and Religious Education Programs - Most Reverend David A. Zubik, Bishop of Pittsburgh II. History and Mission a. History of the Chimbote Mission b. Legacy of Monsignor H. Jules Roos c. Five Core Values of the Chimbote Mission III. Catholic Social Teaching and the Chimbote Mission IV. Chimbote Lesson Plans – Introduction V. Chimbote Lesson Plans – Elementary a. Preschool and Kindergarten – The Boys and Girls of Chimbote b. Grades One and Two – The Bridge to Chimbote c. Grades Three to Five – Valuable Resources d. Grades Six to Eight – A Two-Way Bridge Linking Hearts VI. Chimbote Lesson Plans – Secondary and Youth Ministry a. Grades Nine to Twelve – Bridge to Chimbote: Linking Hearts b. Youth and Young Adult Ministry VII. Classroom Powerpoint Presentation VIII. Classroom Slideshow IX. How Can We Help? X. Mission Saints a. Introduction and On-line link for more detailed information b. St. Therese of Lisieux c. St. Francis Xavier d. St. Rose of Lima e. St. Martin de Porres f. Franciscan Priests Martyred for the Faith in Peru XI. Prayers a. Common Prayers in Spanish b. -

M a N Y F R O M D Io C E S E T O a Tte N D in S T a Lla T Io N a Look at the New

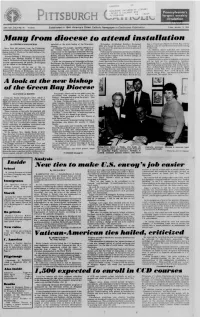

u n i v e r s i t y l i b r a r d u q u e s n e COLBERT STS l o c u s t f c P ennsylvania's P A 1 5 2 1 9 PITTSBURGH . I 1 ■ largest w eekly so ü . I circu la tio n mLLL 139th Year, CXLIV No. 44 15 cents Established in 1844: America’s Oldest Catholic Newspaper in Continuous Publication Friday, January 13. 1984 M any from diocese to attend installation B y STEPHEN KARL1NCHAK installed as the ninth bishop of the W isconsin M ilwaukee Archbishop Rem bert W eakland. that a Protestant church in Green Bay w ill be d i o c e s e . O SB. who heads the province of W isconsin, w ill used as a site lo r closed-circuit television view ing M ore than 120 persons from the Pittsburgh Archbishop Pio Lang hi apostolic delegate to preside over the episcopal installation portion of ol the event Diocese are expected to attend the installation of the Untied States, will be the principal the cerem onies In addition. Kuick said that two television Bishop A dam J. M aida as the ninth bishop of the consecrator for the episcopal ordination. Serving Follow ing the ordination and installation M ass. stations in G reen B ay w ill televise* the ordination Green Bay Diocese. w ith Bishop Leonard as co-consecrator w ill be a reception w ill be held in the Schuldes Sports and installation M ass live from the cathedral He Bishop Aloysius W ycislo, the eighth bishop and Center on the cam pus of St. -

St. John's College

ST. JOHN'S UNIVERSITY NEW YORK Graduate School of Arts and Sciences School of Law Colleges of Liberal Arts and Sciences School of Education College of Business Administration College of Pharmacy Tunior College BACCALAUREATE MASS AND THE NINETY-FOURTH ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT 1964 BACCALAUREATE MASS SATURDAY, JUNE 13, 1964 CelebranL _________________________________________ VERY REVEREND EDWARD J. BURKE, C.M. President, St. John's University Master of Ceremonies ________________________________ REVEREND CARL W. GRINDEL, C.M. Chairman, Department of Philosophy Acolytes ________________________________________________________ REVEREND DANIEL P. MUNDAY, C.M. Academic Vice President REVEREND FREDERICK J. EASTERLY, C.M. Vice-President for Student Personnel Services Baccalaureate Sermon _____________________________ MOST REVEREND JOHN J. KROL, D.D. Archbishop of Philadelphia ACT OF RE-CONSECRATION OF THE UNIVERSITY TO THE IMMACULATE HEART OF MARY VERY REVEREND EDWARD J. BURKE, C.M. President, St. John's University ORDER OF ACADEMIC PROCESSION Grand Marshal ACT OF RE-CONSECRATION OF THE UNIVERSITY TO THE IMMACULATE HEART OF MARY PROFESSOR WERNER ILSEN Queen of the Most Holy Rosary, Help of Christians, Refuge of Mankind, Victress School of Law in all God's battles, we humbly prostrate ourselves before thy throne, confident that we THE COLORS OF THE UNITED STATES shall obtain mercy, grace, bountiful assistance and protection in this present life, not THE UNIVERSITY COLORS through our own inadequate merits upon which we do not rely, hut solely through the great goodness of thy Maternal Heart. Schools and Colleges Assembled in thy name, on the occasion of this Commencement, we the adminis trators, faculties and students of St. John's University, choose this solemn occasion GRADUATE SCHOOL to recall the memory of thy many favors in the past, and to offer to thee the solemn SCHOOL OF LAW homage of our deep and abiding love. -

The Bishops of Pittsburgh and St. Paul Seminary Rev

The Bishops of Pittsburgh and St. Paul Seminary Rev. Frank D. Almade Bishop John J. Wright (early 1960s) Source: Archives of Diocese of Pittsburgh Bishop Wright had a vision. to orphans, the Sisters of Mercy had closed the institution in January of 1965. The diocese saw that the buildings and grounds could Pope John XXIII appointed Bishop John Wright, ordinary of easily be converted into dormitories, classrooms, refectory, kitchen Worcester, the eighth bishop of Pittsburgh on January 23, 1959. and athletic facilities for seminarians. He was already known as an intellectual among the U.S. Catholic bishops. His appointment to the large diocese of Pittsburgh However, by 1965 Bishop Wright saw the national trends of (more than 950,000 souls) was a sign of the pope’s affirmation declining enrollment in college seminaries. Was starting a new col- of his apostolic ability. lege feasible, or even prudent at this time? He also knew the Roman tradition of “colleges,” that is, residences for seminarians The 1950s were a time of great increase in the number of Catholic and aspirants of religious orders while they attended a university parishes, schools and institutions in our country. Upon his arrival in on the other side of a city. He himself had lived at the North Western Pennsylvania Bishop Wright pursued many initiatives in his American College in the 1930’s, while pursuing theological studies new diocese. His grandest was a vision of establishing in his diocese at the Gregorian University in Rome. twelve years of Catholic seminary education for future priests. A decision was made.