Reactions and Perceptions of Economic Agents Within the First Seven Days After the Announcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Africa

339-370/428-S/80005 FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES 1969–1976 VOLUME XXVIII SOUTHERN AFRICA DEPARTMENT OF STATE Washington 339-370/428-S/80005 Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976 Volume XXVIII Southern Africa Editors Myra F. Burton General Editor Edward C. Keefer United States Government Printing Office Washington 2011 339-370/428-S/80005 DEPARTMENT OF STATE Office of the Historian Bureau of Public Affairs For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 339-370/428-S/80005 Preface The Foreign Relations of the United States series presents the official documentary historical record of major foreign policy decisions and significant diplomatic activity of the United States Government. The Historian of the Department of State is charged with the responsibility for the preparation of the Foreign Relations series. The staff of the Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, under the direction of the General Editor, plans, researches, compiles, and edits the volumes in the series. Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg first promulgated official regulations codifying specific standards for the selection and editing of documents for the series on March 26, 1925. Those regulations, with minor modifications, guided the series through 1991. Public Law 102–138, the Foreign Relations Authorization Act, es- tablished a new statutory charter for the preparation of the series which was signed by President George H.W. Bush on October 28, 1991. -

“The Effects of Local Currency Absence to the Banking Market: the Case for Zimbabwe from 2008”

“The effects of local currency absence to the banking market: the case for Zimbabwe from 2008” AUTHORS Charles Nyoka Charles Nyoka (2015). The effects of local currency absence to the banking ARTICLE INFO market: the case for Zimbabwe from 2008. Banks and Bank Systems, 10(2), 15- 22 RELEASED ON Friday, 31 July 2015 JOURNAL "Banks and Bank Systems" FOUNDER LLC “Consulting Publishing Company “Business Perspectives” NUMBER OF REFERENCES NUMBER OF FIGURES NUMBER OF TABLES 0 0 0 © The author(s) 2021. This publication is an open access article. businessperspectives.org Banks and Bank Systems, Volume 10, Issue 2, 2015 Charles Nyoka (South Africa) The effects of local currency absence to the banking market: the case for Zimbabwe from 2008 Abstract Local currency based fee charges have always been one of the major contributors to bank profitability. A profitable banking market has more chances of stability compared to less profitable banking markets. The developments within the Zimbabwean on economy over the last six years merit more attention by researchers than has been given to it over the same period. Zimbabwe adopted a multicurrency approach to banking since the establishment of a government of national unity in 2008. To date the country has remained without a domestic currency a factor that seems to have con- tributed to the demise of some banks in Zimbabwe. Numerous press reports have indicated that Zimbabwean Banks are facing liquidity problems a factor that has culminated in the closer of and the surrendering of bank licences to authori- ties by at least nine banks to date. -

University of Cape Town

Investigating the effects of dollarization on economic growth in Zimbabwe (1990-2015) A Thesis presented to The Graduate School of Business University of Cape Town In partial fulfilment Town of the requirements for the Master of Commerce in Development Finance Degree Cape ofby NHONGERAI NEMARAMBA January 2018 Supervised by: DR. AILIE CHARTERIS University The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derivedTown from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes Capeonly. of Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University PLAGIARISM DECLARATION Declaration 1. I know that plagiarism is wrong. Plagiarism is to use another’s work and pretend that it is one’s own. 2. I have used the American Psychological Association (APA) convention for citation and referencing. Each contribution to, and quotation in, this project from the work(s) of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. 3. This project is my own work. 4. I have not allowed, and will not allow, anyone to copy my work with the intention of passing it off as his or her own work. 5. I acknowledge that copying someone else’s assignment or essay, or part of it, is wrong, and declare that this is my own work. NHONGERAI NEMARAMBA i ABSTRACT This research presents a comprehensive analysis of Zimbabwe’s adoption of a basket of foreign currencies as legal tender and the resultant economic effects of this move. -

Currency Considerations in the Zimbabwean Context 2018

PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS AND AUDITORS BOARD Currency considerations in the Zimbabwean context 26 February 2018 1 1. BACKGROUND 1.1. Zimbabwe witnessed significant monetary and exchange control policy changes in 2016 through to 2017. The changes were a result of continued economic challenges faced by the country that resulted in the liquidity crisis. In response, the RBZ promulgated a series of exchange control operational guidelines and compliance frameworks to alleviate the cash shortage and boost the economy. 1.2. The accountancy profession accepted the positive impact of these measures on entities but also noted some concerns that arose from this policy implementation on the financial reporting of entities in Zimbabwe, hence, this document. 1.3. The aim of this paper is to: I. lay out the functional currency considerations that preparers and auditors are having to make before year end reporting commences; II. outline the relevant International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) implications; and III. offer recommended guidance to preparers of financial statements with the intention of achieving fair and consistent presentation to the benefit of the users. 2. FUNCTIONAL CURRENCY CONSIDERATIONS 2.1. In 2009, Zimbabwe adopted the multi-currency system upon the abandonment of the Zimbabwean dollar (ZW$). For financial reporting purposes (presentation of the national budget and levying of taxes etc.) the government of Zimbabwe adopted the United States Dollars (“USD”) as the functional and reporting currency. Consequently, business also adopted the USD as the functional and reporting currency. 2.2. From the fourth quarter of 2015, there have been notable changes in the availability of foreign currency. This has resulted in a need to assess whether there has been a change in the functional currency. -

Dollarization of the Zimbabwean Economy: Cure Or Curse? the Case of the Teaching and Banking Sectors

CONFERENCE THE RENAISSANCE OF AFRICAN ECONOMIES Dar Es Salam, Tanzania, 20 – 21 / 12 / 2010 LA RENAISSANCE ET LA RELANCE DES ECONOMIES AFRICAINES Dollarization of the Zimbabwean Economy: Cure or Curse? The Case of the Teaching and Banking Sectors Tapiwa Chagonda Post-Doctoral Fellow, Department of Sociology University of Johannesburg 1 Dollarization of the Zimbabwean Economy: Cure or Curse? The Case of the Teaching and Banking Sectors. Tapiwa Chagonda Post-Doctoral Fellow, Department of Sociology University of Johannesburg ABSTRACT This paper analyses the effects of the dollarization of the Zimbabwean economy in 2009, in the wake of devastating hyper-inflation and a political crisis that reached its zenith with the electoral crisis of 2008. Efforts to revive the battered Zimbabwean economy, largely through the dollarization of the Zimbabwean economy are assessed through the lens of the teaching and banking sectors. During the peak of the Zimbabwean crisis in 2008, the teaching sector almost collapsed as partial disintegration at the physical level took its toll on the sector. Most of the primary and secondary school teachers responded to the hyper-inflation that had eroded their incomes by going into the diaspora or joining Zimbabwe’s burgeoning speculative informal economy. The establishment of the Government of National Unity (GNU) saw the dollarization of the Zimbabwean economy and the shelving of the Zimbabwean dollar in March 2009. The above developments saw the teaching sector beginning to show signs of re-integration, as some of the teachers who had left the profession re-joined the sector. This was largely because the dollarization of the Zimbabwean economy ‘killed off’ the speculative activities which were sustaining some of the teachers in the informal economy, during the period of crisis (2000- 2008). -

The Implications of Pegging the Botswana Pula to the U.S. Dollar

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. The Implications of Pegging the Botswana Pula to the U.S. Dollar O. Ochieng INTRODUCTION The practice of peg~ing the currency of one country to another is widespread in the world: of the 141 countries in the world considered as of March 31, 1979, only 32 (23%) national currencies were not pegRed to other currencies and in Africa only 3 out of 41 were unpegGed (Tahle 1); so that the fundamental question of whether to ~eg a currency or not is already a decided matter for many countries, and what often remains to be worked out is, to which currency one should pef one's currency. Judging from the way currencies are moved from one peg to another, it seems that this issue is far from being settled. Once one has decided to peg one's currency to another, there are three policy alternatives to select from: either a country pegs to a single currency; or pegs to a specific basket of currencies; or pegs to Special Drawing Rights (SDR). Pegging a wea~ currency to a single major currency seems to ~e the option that i~ most favoured by less developed countries. The ex-colonial countries generally pegged their currencies to that of their former colonial master at independence. -

ZIMBABWE's UNORTHODOX DOLLARIZATION Erik Bostrom

SAE./No.85/September 2017 Studies in Applied Economics ZIMBABWE'S UNORTHODOX DOLLARIZATION Erik Bostrom Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise Zimbabwe’s Unorthodox Dollarization By Erik Bostrom Copyright 2017 by Erik Bostrom. This work may be reproduced provided that no fee is charged and the original source is properly cited. About the Series The Studies in Applied Economics series is under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, Co-Director of The Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise ([email protected]). The author is mainly a student at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Some of his work was performed as research assistant at the Institute. About the Author Erik Bostrom ([email protected]) is a student at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland and is also a student in the BA/MA program at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) in Washington, D.C. Erik is a junior pursuing a Bachelor’s in International Studies and Economics and a Master’s in International Economics and Strategic Studies. He wrote this paper as an undergraduate researcher at the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise during Summer 2017. Erik will graduate in May 2019 from Johns Hopkins University and in May 2020 from SAIS. Abstract From 2007-2009 Zimbabwe underwent a hyperinflation that culminated in an annual inflation rate of 89.7 sextillion (10^21) percent. Consequently, the government abandoned the local Zimbabwean dollar and adopted a multi-currency system in which several foreign currencies were accepted as legal tender. -

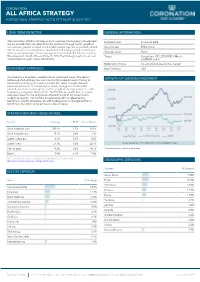

All Africa Strategy Institutional Strategy Fact Sheet As at 30 June 2017

CORONATION ALL AFRICA STRATEGY INSTITUTIONAL STRATEGY FACT SHEET AS AT 30 JUNE 2017 LONG TERM OBJECTIVE GENERAL INFORMATION The Coronation All Africa Strategy aims to maximise the long-term risk-adjusted Inception Date 01 August 2008 returns available from investments on the continent through capital growth of the underlying stocks selected. It is a flexible portfolio primarily invested in listed Strategy Size $78.4 million African equities or stocks listed on developed and emerging market exchanges Strategy Status Open where a substantial part of their earnings are derived from the African continent. The exposure to South Africa is limited to 50%. The Strategy may hold cash and Target Outperform ICE LIBOR USD 3 Month interest bearing assets where appropriate. (US0003M Index) Redemption Terms An anti-dilution levy will be charged INVESTMENT APPROACH Base Currency USD Coronation is a long-term, valuation-driven investment house, focused on GROWTH OF US$100M INVESTMENT bottom-up stock picking. Our aim is to identify mispriced assets trading at discounts to their long-term business value (fair value) through extensive proprietary research. In calculating fair values, through our fundamental research, we focus on through-the-cycle normalised earnings and/or free cash flows using a long-term time horizon. The Portfolio is constructed on a clean- slate basis based on the relative risk-adjusted upside to fair value of each underlying security. The Portfolio is constructed with no reference to a benchmark. We do not equate risk with tracking error, or divergence from a benchmark, but rather with a permanent loss of capital. STRATEGY RETURNS GROSS OF FEES Period Strategy LIBOR Active Return Since inception cum. -

Annual Report 2018

PROSPECT RESOURCES LIMITED / RESOURCES LIMITED / PROSPECT ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT REPORT ANNUAL 2018 30 JUNE 2018 ACN 124 354 329 CORPORATECORPORATE DIRECTORYDIRECTORY DIRECTORS Hugh Warner Sam Hosack Harry Greaves Gerry Fahey Zed Rusike HeNian Chen SECRETARY Andrew Whitten PRINCIPAL OFFICE AUSTRALIA ZIMBABWE Suite 6, 245 Churchill Ave 169 Arcturus Road Subiaco, WA 6008 Greendale, Harare REGISTERED OFFICE Suite 6, 245 Churchill Ave Subiaco, WA 6008 Telephone: (08) 9217 3300 Email: [email protected] AUDITORS Stantons International Level 2 1 Walker Avenue West Perth WA 6005 SHARE REGISTRY Automic Pty Ltd Level 3 50 Holt Street Surry Hills, NSW 2010 Telephone: 1300 288 664 Investor Portal: https://investor.automic.com.au ASX CODE Shares – PSC LEGAL REPRESENTATIVES Whittens & McKeough Pty Limited Level 29, 201 Elizabeth Street Sydney, NSW 2000 PROSPECT RESOURCES LIMITED / ANNUAL REPORT 30 JUNE 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Corporate Directory IFC Chairman’s Statement 1 Review of Operations 3 Directors’ Report 9 Directors’ Declaration 20 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 21 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 22 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 23 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 24 Notes to and Forming Part of the Financial Statements 25 Auditor’s Independence Declaration 52 Independent Auditor’s Report 53 Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) Additional Information 57 I CHAIRMAN'S STATEMENT The Financial Year Ended 30 June 2018 has been an exciting one The drop in the share price of Prospect has not been lost on for Prospect Resources (ASX: PSC) (“Prospect”, the “Company”), our team. We would like to assure our shareholders that every as we transition from explorer to developer. -

The Rhodesian State, Financial Policy and Exchange Control, 1962-1979

Financing Rebellion: The Rhodesian State, Financial Policy and Exchange Control, 1962-1979 By Tinashe Nyamunda SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS IN RESPECT OF THE DOCTORAL DEGREE QUALIFICATION IN AFRICA STUDIES IN THE CENTRE FOR AFRICA STUDIES IN THE FACULTY OF THE HUMANITIES, AT THE UNIVERSITY OF THE FREE STATE NOVEMBER 2015 Supervisor: Prof. I.R. Phimister Co-supervisor: Dr. A.P. Cohen Declaration I declare that the thesis hereby submitted by me for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree at the University of the Free State is my own independent work and has not previously been submitted by me at another university or institution for any degree, diploma, or other qualification. I furthermore cede copyright of the dissertation in favour of the University of the Free State. Signed:……………………. Tinashe Nyamunda Bloemfontein Dedication My wife Patience Mukwambo Nyamunda. My sons, Jamie T. Nyamunda and Christian K. Nyamunda. Without whom I can’t be. Table of Contents Page Abstract ................................................................................................................................ i Opsomming .......................................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. iii Acronyms ............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................... -

Money Demand and Seignorage Maximization Before the End of the Zimbabwean Dollar

Money Demand and Seignorage Maximization before the End of the Zimbabwean Dollar Stephen Matteo Miller and Thandinkosi Ndhlela MERCATUS WORKING PAPER All studies in the Mercatus Working Paper series have followed a rigorous process of academic evaluation, including (except where otherwise noted) at least one double-blind peer review. Working Papers present an author’s provisional findings, which, upon further consideration and revision, are likely to be republished in an academic journal. The opinions expressed in Mercatus Working Papers are the authors’ and do not represent official positions of the Mercatus Center or George Mason University. Stephen Matteo Miller and Thandinkosi Ndhlela. “Money Demand and Seignorage Maximization before the End of the Zimbabwean Dollar.” Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, February 2019. Abstract Unlike most hyperinflations, during Zimbabwe’s recent hyperinflation, as in Revolutionary France, the currency ended before the regime. The empirical results here suggest that the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe operated on the correct side of the inflation tax Laffer curve before abandoning the currency. Estimates of the seignorage- maximizing rate derive from a short-run structural vector autoregression framework using monthly parallel market exchange rate data computed from the ratio of prices from 1999 to 2008 for Old Mutual insurance company’s shares, which trade in London and Harare. Dynamic semi-elasticities generated from orthogonalized impulse response functions -

Currency Code Currency Name Units Per EUR USD US Dollar 1,114282

Currency code Currency name Units per EUR USD US Dollar 1,114282 EUR Euro 1,000000 GBP British Pound 0,891731 INR Indian Rupee 76,833664 AUD Australian Dollar 1,596830 CAD Canadian Dollar 1,463998 SGD Singapore Dollar 1,519556 CHF Swiss Franc 1,097908 MYR Malaysian Ringgit 4,585569 JPY Japanese Yen 120,445338 CNY Chinese Yuan Renminbi 7,657364 NZD New Zealand Dollar 1,660507 THB Thai Baht 34,435083 HUF Hungarian Forint 325,394724 AED Emirati Dirham 4,092202 HKD Hong Kong Dollar 8,705685 MXN Mexican Peso 21,275509 ZAR South African Rand 15,449937 PHP Philippine Peso 56,970569 SEK Swedish Krona 10,508745 IDR Indonesian Rupiah 15576,638324 SAR Saudi Arabian Riyal 4,178559 BRL Brazilian Real 4,190947 TRY Turkish Lira 6,353929 KES Kenyan Shilling 115,893733 KRW South Korean Won 1311,898493 EGP Egyptian Pound 18,508337 IQD Iraqi Dinar 1326,662413 NOK Norwegian Krone 9,632916 KWD Kuwaiti Dinar 0,339171 RUB Russian Ruble 70,335592 DKK Danish Krone 7,465851 PKR Pakistani Rupee 179,387706 ILS Israeli Shekel 3,926669 PLN Polish Zloty 4,255048 QAR Qatari Riyal 4,055988 XAU Gold Ounce 0,000784 OMR Omani Rial 0,428442 COP Colombian Peso 3560,158642 CLP Chilean Peso 770,643233 TWD Taiwan New Dollar 34,639236 ARS Argentine Peso 47,788112 CZK Czech Koruna 25,516024 VND Vietnamese Dong 25847,134851 MAD Moroccan Dirham 10,697013 JOD Jordanian Dinar 0,790026 BHD Bahraini Dinar 0,418970 XOF CFA Franc 655,957000 LKR Sri Lankan Rupee 196,347604 UAH Ukrainian Hryvnia 28,564201 NGN Nigerian Naira 403,643263 TND Tunisian Dinar 3,212774 UGX Ugandan Shilling 4118,051290