The Implications of Pegging the Botswana Pula to the U.S. Dollar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Africa

339-370/428-S/80005 FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES 1969–1976 VOLUME XXVIII SOUTHERN AFRICA DEPARTMENT OF STATE Washington 339-370/428-S/80005 Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976 Volume XXVIII Southern Africa Editors Myra F. Burton General Editor Edward C. Keefer United States Government Printing Office Washington 2011 339-370/428-S/80005 DEPARTMENT OF STATE Office of the Historian Bureau of Public Affairs For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 339-370/428-S/80005 Preface The Foreign Relations of the United States series presents the official documentary historical record of major foreign policy decisions and significant diplomatic activity of the United States Government. The Historian of the Department of State is charged with the responsibility for the preparation of the Foreign Relations series. The staff of the Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, under the direction of the General Editor, plans, researches, compiles, and edits the volumes in the series. Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg first promulgated official regulations codifying specific standards for the selection and editing of documents for the series on March 26, 1925. Those regulations, with minor modifications, guided the series through 1991. Public Law 102–138, the Foreign Relations Authorization Act, es- tablished a new statutory charter for the preparation of the series which was signed by President George H.W. Bush on October 28, 1991. -

List 283 | October 2014

Stephen Album Rare Coins Specializing in Islamic, Indian & Oriental Numismatics P.O. Box 7386, Santa Rosa, CA. 95407, U.S.A. 283 Telephone 707-539-2120 — Fax 707-539-3348 [email protected] Catalog price $5.00 www.stevealbum.com 137187. SAFAVID: Muhammad Khudabandah, 1578-1588, AV ½ OCTOBER 2014 mithqal (2.31g), Mashhad, AH[9]85, A-2616.2, type A, with epithet imam reza, some flatness, some (removable) dirt Gold Coins on obverse, VF, R, ex. Richard Accola collection $350 137186. SAFAVID: Muhammad Khudabandah, 1578-1588, AV mithqal (4.59g), Qazwin, AH[9]89, A-2617.2, type B, some weakness Ancient Gold towards the rim, VF, R, ex. Richard Accola collection $450 137190. SAFAVID: Sultan Husayn, 1694-1722, AV ashrafi (3.47g), Mashhad, AH1130, A-2669E, local design, used only at Mashhad, 138883. ROMAN EMPIRE: Valentinian I, 364-375 AD, AV solidus the site of the tomb of the 8th Shi’ite Imam, ‘Ali b. Musa al-Reza, (4.47g), Thessalonica, bust facing right, pearl-diademed, no weakness, VF, RRR, ex. Richard Accola collection $1,000 draped & cuirassed / Valentinian & Valens seated, holding The obverse text is hoseyn kalb-e astan-e ‘ali, “Husayn, dog at together a globe, Victory behind with outspread wings, the doorstep of ‘Ali.,” with additional royal text in the obverse SMTES below, very tiny rim nick, beautiful bold strike, margin, not found on the standard ashrafis of type #2669. choice EF, R $1,200 By far the most common variety of this type is of the Trier 137217. AFSHARID: Shahrukh, 2nd reign, 1750-1755, AV mohur mint, with Constantinople also relatively common. -

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange As of December 31, 2018

TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2018 COUNTRY-CURRENCY F.C. TO $1.00 AFGHANISTAN - AFGHANI 74.5760 ALBANIA - LEK 107.0500 ALGERIA - DINAR 117.8980 ANGOLA - KWANZA 310.0000 ANTIGUA - BARBUDA - E. CARIBBEAN DOLLAR 2.7000 ARGENTINA-PESO 37.6420 ARMENIA - DRAM 485.0000 AUSTRALIA - DOLLAR 1.4160 AUSTRIA - EURO 0.8720 AZERBAIJAN - NEW MANAT 1.7000 BAHAMAS - DOLLAR 1.0000 BAHRAIN - DINAR 0.3770 BANGLADESH - TAKA 84.0000 BARBADOS - DOLLAR 2.0200 BELARUS - NEW RUBLE 2.1600 BELGIUM-EURO 0.8720 BELIZE - DOLLAR 2.0000 BENIN - CFA FRANC 568.6500 BERMUDA - DOLLAR 1.0000 BOLIVIA - BOLIVIANO 6.8500 BOSNIA- MARKA 1.7060 BOTSWANA - PULA 10.6610 BRAZIL - REAL 3.8800 BRUNEI - DOLLAR 1.3610 BULGARIA - LEV 1.7070 BURKINA FASO - CFA FRANC 568.6500 BURUNDI - FRANC 1790.0000 CAMBODIA (KHMER) - RIEL 4103.0000 CAMEROON - CFA FRANC 603.8700 CANADA - DOLLAR 1.3620 CAPE VERDE - ESCUDO 94.8800 CAYMAN ISLANDS - DOLLAR 0.8200 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC - CFA FRANC 603.8700 CHAD - CFA FRANC 603.8700 CHILE - PESO 693.0800 CHINA - RENMINBI 6.8760 COLOMBIA - PESO 3245.0000 COMOROS - FRANC 428.1400 COSTA RICA - COLON 603.5000 COTE D'IVOIRE - CFA FRANC 568.6500 CROATIA - KUNA 6.3100 CUBA-PESO 1.0000 CYPRUS-EURO 0.8720 CZECH REPUBLIC - KORUNA 21.9410 DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO- FRANC 1630.0000 DENMARK - KRONE 6.5170 DJIBOUTI - FRANC 177.0000 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC - PESO 49.9400 ECUADOR-DOLARES 1.0000 EGYPT - POUND 17.8900 EL SALVADOR-DOLARES 1.0000 EQUATORIAL GUINEA - CFA FRANC 603.8700 ERITREA - NAKFA 15.0000 ESTONIA-EURO 0.8720 ETHIOPIA - BIRR 28.0400 -

The Relationship Between the South African Rand and Commodity Prices: Examining Cointegration and Causality Between the Nominal Asset Classes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE SOUTH AFRICAN RAND AND COMMODITY PRICES: EXAMINING COINTEGRATION AND CAUSALITY BETWEEN THE NOMINAL ASSET CLASSES BY XOLANI NDLOVU [STUDENT NUMBER: 511531] SUPERVISOR: PROF. ERIC SCHALING RESEARCH THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF COMMERCE LAW & MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE MASTER OF MANAGEMENT IN FINANCE & INVESTMENT DEGREE UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND WITS BUSINESS SCHOOL Johannesburg November 2010 “We wa nt to see a competitive and stable exchange rate, nothing more, nothing less.” Tito Mboweni (8 th Governor of the SARB, 1999 -2009) 2 ABSTRACT We employ OLS analysis on a VAR Model to test the “commodity currency” hypothesis of the Rand (i.e. that the currency moves in sympathy with commodity prices) and examine the associated causality using nominal data between 1996 and 2010. We address the question of cointegration using the Engle-Granger test. We find that level series of both assets are difference stationary but not cointegrated. Further, we find the two variables negatively related with strong and significant causality running from commodity prices to the exchange rate and not vice versa, implying exogeneity to the determination of commodity prices with respect to the nominal exchange rate. The strength of the relationship is significantly weaker than other OECD commodity currencies. We surmise that the relationship is dynamic over time owing to the portfolio-rebalance argument and the Commodity Terms of Trade (CTT) effect and in the absence of an error correction mechanism, this disconnect may be prolonged. -

Is the Botswana Pula Misaligned?

BIDPA Working Paper 33 July 2012 Is the Botswana Pula Misaligned? Haile Taye BOTSWANA INSTITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENT POLICY ANALYSIS BIDPA The Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis (BIDPA) is an independent trust, which started operations in 1995 as a non-governmental policy research institution. BIDPA’s mission is to inform policy and build capacity through research and consultancy services. BIDPA is funded by the Botswana government and the African Capacity Building Foundation. BIDPA Working Paper Series The series comprises of papers which reflect work in progress or limited research efforts, which may be of interest to researchers and policy makers, or of a public education character. Working papers may already have been published elsewhere or may appear in other publications. Haile Taye is a Senior Research Fellow at the Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis. ISBN: 99912-65-44-9 © Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis, 2012 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this document are entirely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of BIDPA. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. iv Abstract ................................................................................................................... iv 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 2. Determinants of the Equilibrium Exchange Rate ............................................ -

The Effects of Sentiments on the Dollar Rand (USD/ZAR) Exchange Rate

The effects of sentiments on the dollar rand (USD/ZAR) exchange rate Kgomotso Euginia Mogotlane 772836 A research article submitted to the Faculty of Commerce, Law and Management, University of the Witwatersrand, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Business Administration Johannesburg, 2017 DECLARATION I, Kgomotso Euginia Mogotlane, declare that this research article is my own work except as indicated in the references and acknowledgements. It is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Business Administration in the Graduate School of Business Administration, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination in this or any other university. Kgomotso Euginia Mogotlane Signed at …………………………………………………… On the …………………………….. day of ………………………… 2017 ii DEDICATION This research article is dedicated to the memory of my angels in heaven, may your souls continue to rest in eternal peace, love and light in the presence of our Almighty. I know you always shining down on me from heaven and this is the only way I can shine back. Hope you are all proud of me. I did it for you!!! Samuel Diswantsho Mogotlane. Delia Shirley Mogotlane. Moses Willy Seponana Mogotlane. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank God Almighty, for indeed He is faithful. Jeremiah 29:11 “For I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord. Plans to prosper you and not harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.” I would also like to sincerely thank the following people for their assistance and support throughout my MBA journey: My supervisor, Dr Deenadayalen Konar for his assistance and guidance throughout the research process. -

Treasury Reporting Rates of Exchange As of March 31, 1994

iP.P* r>« •ini u U U ;/ '00 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE AS OF MARCH 31, 1994 DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Financial Management Service FORWARD This report promulgates exchange rate information pursuant to Section 613 of P.L. 87-195 dated September 4, 1961 (22 USC 2363 (b)) which grants the Secretary of the Treasury "sole authority to establish for all foreign currencies or credits the exchange rates at which such currencies are to be reported by all agencies of the Government". The primary purpose of this report is to insure that foreign currency reports prepared by agencies shall be consistent with regularly published Treasury foreign currency reports as to amounts stated in foreign currency units and U.S. dollar equivalents. This covers all foreign currencies in which the U.S. Government has an interest, including receipts and disbursements, accrued revenues and expenditures, authorizations, obligations, receivables and payables, refunds, and similar reverse transaction items. Exceptions to using the reporting rates as shown in the report are collections and refunds to be valued at specified rates set by international agreements, conversions of one foreign currency into another, foreign currencies sold for dollars, and other types of transactions affecting dollar appropriations. (See Volume I Treasury Financial Manual 2-3200 for further details). This quarterly report reflects exchange rates at which the U.S. Government can acquire foreign currencies for official expenditures as reported by disbursing officers for each post on the last business day of the month prior to the date of the published report. Example: The quarterly report as of December 31, will reflect exchange rates reported by disbursing offices as of November 30. -

Assessing the Attractiveness of Cryptocurrencies in Relation to Traditional Investments in South Africa

Assessing the attractiveness of cryptocurrencies in relation to traditional investments in South Africa A Dissertation presented to The Development Finance Centre (DEFIC) Graduate School of Business University of Cape Town In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Commerce in Development FinanceTown by LehlohonoloCape Letho LTHLEH001of February 2019 Supervisor: Dr Grieve Chelwa University The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derivedTown from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes Capeonly. of Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University i PLAGIARISM DECLARATION I know that plagiarism is wrong. Plagiarism is to use another’s work and pretend that it is one’s own. I have used the American Psychological Association 6th edition convention for citation and referencing. Each contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work(s) of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. This dissertation is my own work. I have not allowed, and will not allow, anyone to copy my work with the intention of passing it off as his or her own work. I acknowledge that copying someone else’s assignment or essay, or part of it, is wrong, and declare that this is my own work. Signature________________ Date ____8 February 2019 _____________ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge my supervisor, Dr Grieve Chelwa for the thorough reviews that he provided me with on my research. -

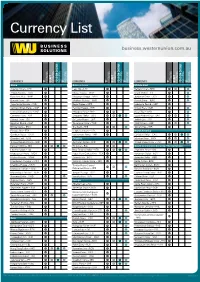

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Purchasing Power Parity Theory for Pula/Rand and Pula/Us Dollar

2020-3704-AJBE – 18 MAY 2020 1 Purchasing Power Parity Theory For Pula/Rand and 2 Pula/Us Dollar Exchange Rates In Botswana 3 * ± 4 By Sethunya Sejoe , Narain Sinha and Zibanani Kahaka 5 6 7 Botswana is heavily dependent on mineral exports which are influenced by 8 Pula Dollar exchange rate. On the otherhand, imports in Botswana are 9 influenced by the Pula Rand exchange rate. This paper attempts to examine 10 the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) theory considering both exchange rates 11 namely Pula/Rand and Pula/US dollar in Botswana for a period of 1976- 12 2016. Five cointegration methods have been employed to determine the 13 validity of the theory between these two exchange rates. The analysis of the 14 results showed that there was no long-run relationship between the variables 15 in both cases of Pula/Rand and Pula/US dollar exchange rates when using 16 the Engle-Granger cointegration method. Johansen cointegration test 17 inidicates one cointegrating vector. However, error correction model (ECM) 18 showed rapid deviation of the variables to the long-run equilibrium, 19 indicating a short-run cointegration relationship for Pula/Rand and Pula/US 20 dollar exchange rates. A further investigation of a long-run PPP was 21 conducted using the autoregressive distribution lag model (ARDL) bond 22 approach. The results showed that the variables were cointegrated with each 23 other for both Botswana and South Africa and between Botswana and 24 United States of America. This indicated a long-run association between the 25 variables and validated the long-run PPP theory between Botswana and 26 South Africa and between Botswana and United States of America. -

BTA Annual Report 2009 English.Pdf

regulation in a liBeralised market Botswana telecommunications authority annual rePort 2009 09 CONTENTS 2 Chairman’s Statement 4 Chief Executive’s Statement 6 Board of Directors 8 Management 10 Corporate Governance 14 Engineering Review 16 Broadcasting Regulation Issues 18 Market Development 24 Compliance and Consumer Affairs 26 Public Relations 30 Corporate Strategy 34 Financial Review 37 Conclusion 40 Annual Financial Statements Botswana telecommunications authority Annual Report 2009 Surplus for the year (Pula) Revenue v Expenditure 80 70 60 50 40 Pula Million 30 20 6,563,953 10 18,173,982 12,037,490 - 2009 2008 2007 2009 2008 2007 Revenue Expenditure Cash from Revenue Source operations v Capex 30 25 20 15 Pula Million 10 Turnover fees 81% 5 Radio Licence fees 13% System Licence fees 5% - Service Licence fees 1% 2007 2008 2009 Cash from operations Capex BotSwana telecommunIcatIonS authorIty Annual Report 2009 results for the year ended 31 march 2009 the members of the Board of Botswana telecommunications authority have pleasure in announcing the audited financial results of the authority for the year ended 31 march 2009. 2009 2008 2009 2008 Income Statement Pula Pula cashflow Statement Pula Pula Revenue 71,247,170 61,085,480 Cashflow from Operating Other income 1,851,509 1,113,034 Activities 22,184,767 29,217,251 Contribution to Universal Service Fund (4,000,000 ) — Cash generated from operations 16,575,960 25,124,109 Operating expenses (56,533,504 ) (54,254,166 ) Finance income 5,608,807 4,093,142 Finance income 5,608,807 4,093,142 -

South Africans, Cryptocurrencies and Taxation

May 2018 Research report South Africans, Cryptocurrencies and Taxation Page 1 of 46 Page 2 of 46 CONTENTS Introduction 4 Hypotheses 5 Methodology 5 Findings 7 1. Market size 7 2. Forecast growth 9 3. Motivations for buying cryptocurrencies 11 2017: the year of “get rich quick” 11 Long term HODLers & professional curiosity 13 High-frequency traders 16 Emergency funds and goal-based savings 16 Untraceable transactions 17 4. Portfolio size and diversification 18 5. Platforms, exchanges, apps and tools 21 6. Perceptions of cryptocurrency taxation amongst investors 25 7. Perceptions of cryptocurrency taxation amongst tax professionals 28 Levels of comfort advising around tax and cryptocurrency 28 Opinions on cryptocurrency taxation 29 Risks for tax professionals 31 Data wrangling is a major pain point 32 Creating a paper trail 32 8. Taxation: the evolving regulatory framework 35 Conclusion 37 9. Demographics 38 Conclusion 42 Appendices 43 Appendix A: Research Limitations 43 Appendix B: Survey questions 44 Page 3 of 46 INTRODUCTION Introduction Although Satoshi Nakamoto’s white paper introducing the concept of Bitcoin to the world was first published a full decade ago, South African interest in cryptocurrencies was mostly confined to niche tech and finance communities. This all changed during 2017, when local interest in cryptocurrencies became stratospheric. In fact, over the past 12 months, South Africa had the highest search interest in “Bitcoin” on Google for any region in the world1. But beyond the interest, little substantive research has been done into how many South Africans are actually buying, trading and “hodling” cryptocurrencies, and why, and public understanding about how cryptocurrency behaviour is taxed.