Money Demand and Seignorage Maximization Before the End of the Zimbabwean Dollar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Africa

339-370/428-S/80005 FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES 1969–1976 VOLUME XXVIII SOUTHERN AFRICA DEPARTMENT OF STATE Washington 339-370/428-S/80005 Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976 Volume XXVIII Southern Africa Editors Myra F. Burton General Editor Edward C. Keefer United States Government Printing Office Washington 2011 339-370/428-S/80005 DEPARTMENT OF STATE Office of the Historian Bureau of Public Affairs For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 339-370/428-S/80005 Preface The Foreign Relations of the United States series presents the official documentary historical record of major foreign policy decisions and significant diplomatic activity of the United States Government. The Historian of the Department of State is charged with the responsibility for the preparation of the Foreign Relations series. The staff of the Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, under the direction of the General Editor, plans, researches, compiles, and edits the volumes in the series. Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg first promulgated official regulations codifying specific standards for the selection and editing of documents for the series on March 26, 1925. Those regulations, with minor modifications, guided the series through 1991. Public Law 102–138, the Foreign Relations Authorization Act, es- tablished a new statutory charter for the preparation of the series which was signed by President George H.W. Bush on October 28, 1991. -

On the Measurement of Zimbabwe's Hyperinflation

18485_CATO-R2(pps.):Layout 1 8/7/09 3:55 PM Page 353 On the Measurement of Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflation Steve H. Hanke and Alex K. F. Kwok Zimbabwe experienced the first hyperinflation of the 21st centu- ry.1 The government terminated the reporting of official inflation sta- tistics, however, prior to the final explosive months of Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation. We demonstrate that standard economic theory can be applied to overcome this apparent insurmountable data problem. In consequence, we are able to produce the only reliable record of the second highest inflation in world history. The Rogues’ Gallery Hyperinflations have never occurred when a commodity served as money or when paper money was convertible into a commodity. The curse of hyperinflation has only reared its ugly head when the supply of money had no natural constraints and was governed by a discre- tionary paper money standard. The first hyperinflation was recorded during the French Revolution, when the monthly inflation rate peaked at 143 percent in December 1795 (Bernholz 2003: 67). More than a century elapsed before another hyperinflation occurred. Not coincidentally, the inter- Cato Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009). Copyright © Cato Institute. All rights reserved. Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics at The Johns Hopkins University and a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute. Alex K. F. Kwok is a Research Associate at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise at The Johns Hopkins University. 1In this article, we adopt Phillip Cagan’s (1956) definition of hyperinflation: a price level increase of at least 50 percent per month. -

“The Effects of Local Currency Absence to the Banking Market: the Case for Zimbabwe from 2008”

“The effects of local currency absence to the banking market: the case for Zimbabwe from 2008” AUTHORS Charles Nyoka Charles Nyoka (2015). The effects of local currency absence to the banking ARTICLE INFO market: the case for Zimbabwe from 2008. Banks and Bank Systems, 10(2), 15- 22 RELEASED ON Friday, 31 July 2015 JOURNAL "Banks and Bank Systems" FOUNDER LLC “Consulting Publishing Company “Business Perspectives” NUMBER OF REFERENCES NUMBER OF FIGURES NUMBER OF TABLES 0 0 0 © The author(s) 2021. This publication is an open access article. businessperspectives.org Banks and Bank Systems, Volume 10, Issue 2, 2015 Charles Nyoka (South Africa) The effects of local currency absence to the banking market: the case for Zimbabwe from 2008 Abstract Local currency based fee charges have always been one of the major contributors to bank profitability. A profitable banking market has more chances of stability compared to less profitable banking markets. The developments within the Zimbabwean on economy over the last six years merit more attention by researchers than has been given to it over the same period. Zimbabwe adopted a multicurrency approach to banking since the establishment of a government of national unity in 2008. To date the country has remained without a domestic currency a factor that seems to have con- tributed to the demise of some banks in Zimbabwe. Numerous press reports have indicated that Zimbabwean Banks are facing liquidity problems a factor that has culminated in the closer of and the surrendering of bank licences to authori- ties by at least nine banks to date. -

University of Cape Town

Investigating the effects of dollarization on economic growth in Zimbabwe (1990-2015) A Thesis presented to The Graduate School of Business University of Cape Town In partial fulfilment Town of the requirements for the Master of Commerce in Development Finance Degree Cape ofby NHONGERAI NEMARAMBA January 2018 Supervised by: DR. AILIE CHARTERIS University The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derivedTown from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes Capeonly. of Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University PLAGIARISM DECLARATION Declaration 1. I know that plagiarism is wrong. Plagiarism is to use another’s work and pretend that it is one’s own. 2. I have used the American Psychological Association (APA) convention for citation and referencing. Each contribution to, and quotation in, this project from the work(s) of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. 3. This project is my own work. 4. I have not allowed, and will not allow, anyone to copy my work with the intention of passing it off as his or her own work. 5. I acknowledge that copying someone else’s assignment or essay, or part of it, is wrong, and declare that this is my own work. NHONGERAI NEMARAMBA i ABSTRACT This research presents a comprehensive analysis of Zimbabwe’s adoption of a basket of foreign currencies as legal tender and the resultant economic effects of this move. -

Zimbabwe After Hyperinflation: in Dollars They Trust | the Economist

Zimbabwe after hyperinflation: In dollars they trust | The Economist http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21576665-grub... Zimbabwe after hyperinflation Grubby greenbacks, dear credit, full shops and empty factories Apr 27th 2013 | HARARE | From the print edition THE OK Mart store in Braeside, a suburb of Harare, is doing a brisk business on a sunny Saturday morning. The store, owned by OK Zimbabwe, a retail chain, is the country’s largest. It stocks as wide a range of groceries and household Small change, old and new goods as any large supermarket in America or Europe. Most are imports. For those who find the branded goods a little pricey, OK Zimbabwe offers its own-label Top Notch range of electrical goods made in China. The industrial district farther south of the city centre looks rather less prosperous. Food manufacturers and textile firms have down-at-heel outposts here. Half a dozen oilseed silos lie empty. Only a few local manufacturers are still spry enough to get their products into OK stores. One is Delta, a brewer that also bottles Coca-Cola. Another is BAT Zimbabwe, whose cigarette brands include Newbury and Madison. This lopsided economy is a legacy of the collapse of Zimbabwe’s currency. Inflation reached an absurd 231,000,000% in the summer of 2008. Output measured in dollars had halved in barely a decade. A hundred-trillion-dollar note was made ready for circulation, but no sane tradesman would accept local banknotes. A ban on foreign-currency trading was lifted in January 2009. By then the American dollar had become Zimbabwe’s main currency, a position it still holds today. -

Currency Considerations in the Zimbabwean Context 2018

PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS AND AUDITORS BOARD Currency considerations in the Zimbabwean context 26 February 2018 1 1. BACKGROUND 1.1. Zimbabwe witnessed significant monetary and exchange control policy changes in 2016 through to 2017. The changes were a result of continued economic challenges faced by the country that resulted in the liquidity crisis. In response, the RBZ promulgated a series of exchange control operational guidelines and compliance frameworks to alleviate the cash shortage and boost the economy. 1.2. The accountancy profession accepted the positive impact of these measures on entities but also noted some concerns that arose from this policy implementation on the financial reporting of entities in Zimbabwe, hence, this document. 1.3. The aim of this paper is to: I. lay out the functional currency considerations that preparers and auditors are having to make before year end reporting commences; II. outline the relevant International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) implications; and III. offer recommended guidance to preparers of financial statements with the intention of achieving fair and consistent presentation to the benefit of the users. 2. FUNCTIONAL CURRENCY CONSIDERATIONS 2.1. In 2009, Zimbabwe adopted the multi-currency system upon the abandonment of the Zimbabwean dollar (ZW$). For financial reporting purposes (presentation of the national budget and levying of taxes etc.) the government of Zimbabwe adopted the United States Dollars (“USD”) as the functional and reporting currency. Consequently, business also adopted the USD as the functional and reporting currency. 2.2. From the fourth quarter of 2015, there have been notable changes in the availability of foreign currency. This has resulted in a need to assess whether there has been a change in the functional currency. -

Dollarization of the Zimbabwean Economy: Cure Or Curse? the Case of the Teaching and Banking Sectors

CONFERENCE THE RENAISSANCE OF AFRICAN ECONOMIES Dar Es Salam, Tanzania, 20 – 21 / 12 / 2010 LA RENAISSANCE ET LA RELANCE DES ECONOMIES AFRICAINES Dollarization of the Zimbabwean Economy: Cure or Curse? The Case of the Teaching and Banking Sectors Tapiwa Chagonda Post-Doctoral Fellow, Department of Sociology University of Johannesburg 1 Dollarization of the Zimbabwean Economy: Cure or Curse? The Case of the Teaching and Banking Sectors. Tapiwa Chagonda Post-Doctoral Fellow, Department of Sociology University of Johannesburg ABSTRACT This paper analyses the effects of the dollarization of the Zimbabwean economy in 2009, in the wake of devastating hyper-inflation and a political crisis that reached its zenith with the electoral crisis of 2008. Efforts to revive the battered Zimbabwean economy, largely through the dollarization of the Zimbabwean economy are assessed through the lens of the teaching and banking sectors. During the peak of the Zimbabwean crisis in 2008, the teaching sector almost collapsed as partial disintegration at the physical level took its toll on the sector. Most of the primary and secondary school teachers responded to the hyper-inflation that had eroded their incomes by going into the diaspora or joining Zimbabwe’s burgeoning speculative informal economy. The establishment of the Government of National Unity (GNU) saw the dollarization of the Zimbabwean economy and the shelving of the Zimbabwean dollar in March 2009. The above developments saw the teaching sector beginning to show signs of re-integration, as some of the teachers who had left the profession re-joined the sector. This was largely because the dollarization of the Zimbabwean economy ‘killed off’ the speculative activities which were sustaining some of the teachers in the informal economy, during the period of crisis (2000- 2008). -

On the Measurement of Zimbabwe's Hyperinflation

18485_CATO-R2(pps.):Layout 1 8/7/09 3:55 PM Page 353 On the Measurement of Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflation Steve H. Hanke and Alex K. F. Kwok Zimbabwe experienced the first hyperinflation of the 21st centu - ry. 1 The government terminated the reporting of official inflation sta - tistics, however, prior to the final explosive months of Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation. We demonstrate that standard economic theory can be applied to overcome this apparent insurmountable data problem. In consequence, we are able to produce the only reliable record of the second highest inflation in world history. The Rogues’ Gallery Hyperinflations have never occurred when a commodity served as money or when paper money was convertible into a commodity. The curse of hyperinflation has only reared its ugly head when the supply of money had no natural constraints and was governed by a discre - tionary paper money standard. The first hyperinflation was recorded during the French Revolution, when the monthly inflation rate peaked at 143 percent in December 1795 (Bernholz 2003: 67). More than a century elapsed before another hyperinflation occurred. Not coincidentally, the inter- Cato Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009). Copyright © Cato Institute. All rights reserved. Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics at The Johns Hopkins University and a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute. Alex K. F. Kwok is a Research Associate at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise at The Johns Hopkins University. 1In this article, we adopt Phillip Cagan’s (1956) definition of hyperinflation: a price level increase of at least 50 percent per month. -

The Implications of Pegging the Botswana Pula to the U.S. Dollar

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. The Implications of Pegging the Botswana Pula to the U.S. Dollar O. Ochieng INTRODUCTION The practice of peg~ing the currency of one country to another is widespread in the world: of the 141 countries in the world considered as of March 31, 1979, only 32 (23%) national currencies were not pegRed to other currencies and in Africa only 3 out of 41 were unpegGed (Tahle 1); so that the fundamental question of whether to ~eg a currency or not is already a decided matter for many countries, and what often remains to be worked out is, to which currency one should pef one's currency. Judging from the way currencies are moved from one peg to another, it seems that this issue is far from being settled. Once one has decided to peg one's currency to another, there are three policy alternatives to select from: either a country pegs to a single currency; or pegs to a specific basket of currencies; or pegs to Special Drawing Rights (SDR). Pegging a wea~ currency to a single major currency seems to ~e the option that i~ most favoured by less developed countries. The ex-colonial countries generally pegged their currencies to that of their former colonial master at independence. -

ZIMBABWE's UNORTHODOX DOLLARIZATION Erik Bostrom

SAE./No.85/September 2017 Studies in Applied Economics ZIMBABWE'S UNORTHODOX DOLLARIZATION Erik Bostrom Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise Zimbabwe’s Unorthodox Dollarization By Erik Bostrom Copyright 2017 by Erik Bostrom. This work may be reproduced provided that no fee is charged and the original source is properly cited. About the Series The Studies in Applied Economics series is under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, Co-Director of The Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise ([email protected]). The author is mainly a student at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Some of his work was performed as research assistant at the Institute. About the Author Erik Bostrom ([email protected]) is a student at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland and is also a student in the BA/MA program at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) in Washington, D.C. Erik is a junior pursuing a Bachelor’s in International Studies and Economics and a Master’s in International Economics and Strategic Studies. He wrote this paper as an undergraduate researcher at the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and the Study of Business Enterprise during Summer 2017. Erik will graduate in May 2019 from Johns Hopkins University and in May 2020 from SAIS. Abstract From 2007-2009 Zimbabwe underwent a hyperinflation that culminated in an annual inflation rate of 89.7 sextillion (10^21) percent. Consequently, the government abandoned the local Zimbabwean dollar and adopted a multi-currency system in which several foreign currencies were accepted as legal tender. -

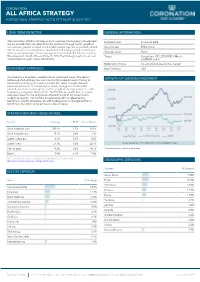

All Africa Strategy Institutional Strategy Fact Sheet As at 30 June 2017

CORONATION ALL AFRICA STRATEGY INSTITUTIONAL STRATEGY FACT SHEET AS AT 30 JUNE 2017 LONG TERM OBJECTIVE GENERAL INFORMATION The Coronation All Africa Strategy aims to maximise the long-term risk-adjusted Inception Date 01 August 2008 returns available from investments on the continent through capital growth of the underlying stocks selected. It is a flexible portfolio primarily invested in listed Strategy Size $78.4 million African equities or stocks listed on developed and emerging market exchanges Strategy Status Open where a substantial part of their earnings are derived from the African continent. The exposure to South Africa is limited to 50%. The Strategy may hold cash and Target Outperform ICE LIBOR USD 3 Month interest bearing assets where appropriate. (US0003M Index) Redemption Terms An anti-dilution levy will be charged INVESTMENT APPROACH Base Currency USD Coronation is a long-term, valuation-driven investment house, focused on GROWTH OF US$100M INVESTMENT bottom-up stock picking. Our aim is to identify mispriced assets trading at discounts to their long-term business value (fair value) through extensive proprietary research. In calculating fair values, through our fundamental research, we focus on through-the-cycle normalised earnings and/or free cash flows using a long-term time horizon. The Portfolio is constructed on a clean- slate basis based on the relative risk-adjusted upside to fair value of each underlying security. The Portfolio is constructed with no reference to a benchmark. We do not equate risk with tracking error, or divergence from a benchmark, but rather with a permanent loss of capital. STRATEGY RETURNS GROSS OF FEES Period Strategy LIBOR Active Return Since inception cum. -

Zimbabwe Crisis Reports Issue 16

ZIMBABWE CRISIS REPORTS Issue 16 ■ October 2007 Fresh insights into the Zimbabwean situation CENTRAL BANKER DISSENTS OVER NATIONALISATION The ZANU-PF administration presses ahead with a plan to take a controlling share in foreign-owned businesses, despite warnings about the consequences. By Mike Nyoni in Harare The Zimbabwean authorities are pressing ahead with a nationalisation scheme despite warnings from the country’s central banker that the economic effects will be ruinous. The dispute highlights the schism Lazele Credit: between politicians who place Main branch of Standard Chartered Bank in Harare. Picture taken October 17. ideological policies above pragmatism, and the technocrats in the administration. Zimbabweans. After the upper Mangwana likened the planned chamber, the Senate, passed the law takeover of foreign banks, mining and On September 26, the lower house of on October 2, only President Robert manufacturing firms to the parliament passed the Indigenisation Mugabe’s assent is required for it to government’s seizure of commercial and Empowerment Bill, which will enter into force. farms which started in 2000 — a move compel foreign-owned firms, including which critics say has been mining companies and banks, to cede Defending the bill in the lower counterproductive, destroying farming 51 per cent of their shares to black chamber, Indigenisation Minister Paul and ultimately the wider economy. NEWS IN BRIEF ■ Zimbabawe’s main opposition lobbying for a new constitution. At say Germany is opposed to the idea party, the Movement for Democratic least 20 students were arrested and while Nordic states agree with Change, said on October 15 that others were injured after being Brown.