'Inclusive Government' : Some Observations on Its First 100 Days

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada Sanctions Zimbabwe

Canadian Sanctions and Canadian charities operating in Zimbabwe: Be Very Careful! By Mark Blumberg (January 7, 2009) Canadian charities operating in Zimbabwe need to be extremely careful. It is not the place for a new and inexperienced charity to begin foreign operations. In fact, only Canadian charities with substantial experience in difficult international operations should even consider operating in Zimbabwe. It is one of the most difficult countries to carry out charitable operations by virtue of the very difficult political, security, human rights and economic situation and the resultant Canadian and international sanctions. This article will set out some information on the Zimbabwe Sanctions including the full text of the Act and Regulations governing the sanctions. It is not a bad idea when dealing with difficult legal issues to consult knowledgeable legal advisors. Summary On September 4, 2008, the Special Economic Measures (Zimbabwe) Regulations (SOR/2008-248) (the “Regulations”) came into force pursuant to subsections 4(1) to (3) of the Special Economic Measures Act. The Canadian sanctions against Zimbabwe are targeted sanctions dealing with weapons, technical support for weapons, assets of designated persons, and Zimbabwean aircraft landing in Canada. There is no humanitarian exception to these targeted sanctions. There are tremendous practical difficulties working in Zimbabwe and if a Canadian charity decides to continue operating in Zimbabwe it is important that the Canadian charity and its intermediaries (eg. Agents, contractor, partners) avoid providing any benefits, “directly or indirectly”, to a “designated person”. Canadian charities need to undertake rigorous due diligence and risk management to ensure that a “designated person” does not financially benefit from the program. -

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe – ZWE36759 – Movement for Democratic Change – Returnees – Spies – Traitors – Passports – Travel Restrictions 21 June 2010

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe – ZWE36759 – Movement for Democratic Change – Returnees – Spies – Traitors – Passports – Travel restrictions 21 June 2010 1. Deleted. 2. Deleted. 3. Please provide a general update on the situation for Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) members, both rank and file members and prominent leaders, in respect to their possible treatment and risk of serious harm in Zimbabwe. The situation for MDC members is precarious, as is borne out by the following reports which indicate that violence is perpetrated against them with impunity by Zimbabwean police and other Law and Order personnel such as the army and pro-Mugabe youth militias. Those who are deemed to be associated with the MDC party either by family ties or by employment are also adversely treated. The latest Country of Origin Information Report from the UK Home Office in December 2009 provides recent chronology of incidents from July 2009 to December 2009 where MDC members and those believed to be associated with them were adversely treated. It notes that there has been a decrease in violent incidents in some parts of the country; however, there was also a suspension of the production of the „Monthly Political Violence Reports‟ by the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum (ZHRF), so that there has not been a comprehensive accounting of incidents: POLITICALLY MOTIVATED VIOLENCE Some areas of Zimbabwe are hit harder by violence 5.06 Reporting on 30 June 2009, the Solidarity Peace Trust noted that: An uneasy calm prevails in some parts of the country, while in others tensions remain high in the wake of the horrific violence of 2008…. -

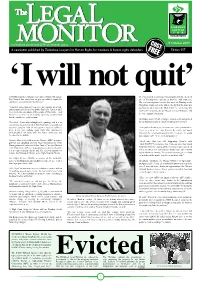

19 October 2009 Edition

19 October 2009 Edition 017 HARARE-Embattled‘I Deputy Agriculturewill Minister-Designate not quit’He was ordered to surrender his passport and title deeds of Roy Bennett has vowed not to give up politics despite his one of his properties and not to interfere with witnesses. continued ‘persecution and harassment.’ His trial was supposed to start last week on Tuesday at the Magistrate Court, only to be told on the day that the State was “I am here for as long as I can serve my country, my people applying to indict him to the High Court. The application was and my party to the best of my ability. Basically, I am here until granted the following day by Magistrate Lucy Mungwira and we achieve the aspirations of the people of Zimbabwe,” said he was committed to prison. Bennett in an interview on Saturday, quashing any likelihood that he would leave politics soon. On Friday, Justice Charles Hungwe reinstated his bail granted He added: “I have often thought of it (quitting) and it is an by the Supreme Court in March, resulting in his release. easiest thing to do, by the way. But if you have a constituency you have stood in front of and together you have suffered, “It is good to be out again, it is not a nice place (prison) to be. there is no easy walking away from that constituency. There are a lot of lice,” said Bennett. He said he had hoped So basically I am there until we return democracy and that with the transitional government in existence he would freedoms to Zimbabwe.” not continue to be ‘persecuted and harassed”. -

University of St. Thomas Presents Morgan Tsvangirai and Roy Bennett Walk with Me: ‘The Struggle for Freedom and Hope in Zimbabwe’

News Release Contact: Sandra Soliz 713-906-7912 [email protected] University of St. Thomas presents Morgan Tsvangirai and Roy Bennett Walk with Me: ‘The Struggle for Freedom and Hope in Zimbabwe’ WHAT: University of St. Thomas presents two of the most effective opposition leaders in Zimbabwe today, Morgan Tsvangirai and Roy Bennett, discussing the current political and social situation in Zimbabwe. WHEN: 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 9 WHERE: Cullen Hall, 4001 Mt. Vernon University of St. Thomas Parking available in the Moran Center, Graustark and West Alabama BACKGROUND: • Zimbabwe, 10 years ago the breadbasket of Africa, now faces mass starvation. Land seizures, slum “clearance” and price controls have left fields brown, stores empty and cities dark. People have no jobs, no transport, and no food. • Life expectancy for men has fallen from 60 to 37, lowest in the world. For women, it is lower, 34. Twelve million people once lived in Zimbabwe; more than three million have fled. • The Movement for Democratic Change, led by former union leader Morgan Tsvangirai, opposing these policies, won 58 of the 120 elected seats in Parliament in the last largely free elections of 2000. The Government of President Robert Mugabe closed newspapers, banned political meetings, arrested its opponents. • Today Zimbabwe’s African neighbors, as well as the nations of Europe and America are calling for free and fair elections, but Mugabe stubbornly clings to power. more University of St. Thomas… A Shining Star in the Heart of Houston since 1947 3800 Montrose Blvd. Houston, TX 77006 713.522.7911 www.stthom.edu University of St. -

The Colour of Murder: One Family's Horror Exposes a Nation's Anguish / Heidi Holland

The colour of murder: one family's horror exposes a nation's anguish / Heidi Holland 0143025120, 9780143025122 / 2006 / Heidi Holland / Penguin, 2006 / The colour of murder: one family's horror exposes a nation's anguish / 270 pages / file download rov.pdf Social Science / ISBN:9780143527855 / Sep 26, 2012 / Africa's traditional beliefs - including ancestor worship, divination and witchcraft - continue to dominate its spiritual influences. Readers in search of a better / African Magic / Heidi Holland colour family's horror anguish The colour of murder: one family's horror exposes a nation's anguish pdf download Born in Soweto / UCAL:B4104500 / Soweto (South Africa) / Inside the Heart of South Africa / 202 pages / Heidi Holland / Soweto, a sprawling urban city, home to four million people, became an icon of the apartheid era, infamous around the world for its violence, filthy streets and rickety shacks / 1994 pdf file 2002 / Stories about Africa's Infamous City / Heidi Holland, Adam Roberts / From Jo'burg to Jozi / 258 pages / History / STANFORD:36105112805622 / The authors approached about eighty journalists and writers based in Johannesburg and asked them to write short pieces about the city in which they work and live. They did not The murder: download Heidi Holland / Sep 28, 2012 / Despite the African National Congress being at the height of its powers, its future is today less certain than at any time in its long history. In the past, the liberation / 100 Years of Struggle - Mandela's ANC / ISBN:9780143529132 / 240 pages / Social Science nation's 280 pages / 'I don't make enemies. Others make me an enemy of theirs.' Robert Mugabe, exclusive interview The man behind the monster . -

Dealing with the Crisis in Zimbabwe: the Role of Economics, Diplomacy, and Regionalism

SMALL WARS JOURNAL smallwarsjournal.com Dealing with the Crisis in Zimbabwe: The Role of Economics, Diplomacy, and Regionalism Logan Cox and David A. Anderson Introduction Zimbabwe (formerly known as Rhodesia) shares a history common to most of Africa: years of colonization by a European power, followed by a war for independence and subsequent autocratic rule by a leader in that fight for independence. Zimbabwe is, however, unique in that it was once the most diverse and promising economy on the continent. In spite of its historical potential, today Zimbabwe ranks third worst in the world in “Indicators of Instability” leading the world in Human Flight, Uneven Development, and Economy, while ranking high in each of the remaining eight categories tracked (see figure below)1. Zimbabwe is experiencing a “brain drain” with the emigration of doctors, engineers, and agricultural experts, the professionals that are crucial to revitalizing the Zimbabwean economy2. If this was not enough, 2008 inflation was running at an annual rate of 231 million percent, with 80% of the population lives below the poverty line.3 Figure 1: Source: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=4350&page=0 1 Foreign Policy, “The Failed States Index 2008”, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=4350&page=0, (accessed August 29, 2008). 2 The Fund for Peace, “Zimbabwe 2007.” The Fund for Peace. http://www.fundforpeace.org/web/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=280&Itemid=432 (accessed September 30, 2008). 3 BBC News, “Zimbabwean bank issues new notes,” British Broadcasting Company. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7642046.stm (accessed October 3, 2008). -

On the Measurement of Zimbabwe's Hyperinflation

18485_CATO-R2(pps.):Layout 1 8/7/09 3:55 PM Page 353 On the Measurement of Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflation Steve H. Hanke and Alex K. F. Kwok Zimbabwe experienced the first hyperinflation of the 21st centu- ry.1 The government terminated the reporting of official inflation sta- tistics, however, prior to the final explosive months of Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation. We demonstrate that standard economic theory can be applied to overcome this apparent insurmountable data problem. In consequence, we are able to produce the only reliable record of the second highest inflation in world history. The Rogues’ Gallery Hyperinflations have never occurred when a commodity served as money or when paper money was convertible into a commodity. The curse of hyperinflation has only reared its ugly head when the supply of money had no natural constraints and was governed by a discre- tionary paper money standard. The first hyperinflation was recorded during the French Revolution, when the monthly inflation rate peaked at 143 percent in December 1795 (Bernholz 2003: 67). More than a century elapsed before another hyperinflation occurred. Not coincidentally, the inter- Cato Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009). Copyright © Cato Institute. All rights reserved. Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics at The Johns Hopkins University and a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute. Alex K. F. Kwok is a Research Associate at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise at The Johns Hopkins University. 1In this article, we adopt Phillip Cagan’s (1956) definition of hyperinflation: a price level increase of at least 50 percent per month. -

B COUNCIL DECISION 2011/101/CFSP of 15 February 2011 Concerning Restrictive Measures Against Zimbabwe (OJ L 42, 16.2.2011, P

2011D0101 — EN — 20.02.2014 — 004.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL DECISION 2011/101/CFSP of 15 February 2011 concerning restrictive measures against Zimbabwe (OJ L 42, 16.2.2011, p. 6) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Council Decision 2012/97/CFSP of 17 February 2012 L 47 50 18.2.2012 ►M2 Council Implementing Decision 2012/124/CFSP of 27 February 2012 L 54 20 28.2.2012 ►M3 Council Decision 2013/89/CFSP of 18 February 2013 L 46 37 19.2.2013 ►M4 Council Decision 2013/160/CFSP of 27 March 2013 L 90 95 28.3.2013 ►M5 Council Implementing Decision 2013/469/CFSP of 23 September 2013 L 252 31 24.9.2013 ►M6 Council Decision 2014/98/CFSP of 17 February 2014 L 50 20 20.2.2014 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 100, 14.4.2011, p. 74 (2011/101/CFSP) 2011D0101 — EN — 20.02.2014 — 004.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL DECISION 2011/101/CFSP of 15 February 2011 concerning restrictive measures against Zimbabwe THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in particular Article 29 thereof, Whereas: (1) On 19 February 2004, the Council adopted Common Position 2004/161/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Zimb abwe (1 ). (2) Council Decision 2010/92/CFSP (2 ), adopted on 15 February 2010, extended the restrictive measures provided for in Common Position 2004/161/CFSP until 20 February 2011. -

Zimbabwe After Hyperinflation: in Dollars They Trust | the Economist

Zimbabwe after hyperinflation: In dollars they trust | The Economist http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21576665-grub... Zimbabwe after hyperinflation Grubby greenbacks, dear credit, full shops and empty factories Apr 27th 2013 | HARARE | From the print edition THE OK Mart store in Braeside, a suburb of Harare, is doing a brisk business on a sunny Saturday morning. The store, owned by OK Zimbabwe, a retail chain, is the country’s largest. It stocks as wide a range of groceries and household Small change, old and new goods as any large supermarket in America or Europe. Most are imports. For those who find the branded goods a little pricey, OK Zimbabwe offers its own-label Top Notch range of electrical goods made in China. The industrial district farther south of the city centre looks rather less prosperous. Food manufacturers and textile firms have down-at-heel outposts here. Half a dozen oilseed silos lie empty. Only a few local manufacturers are still spry enough to get their products into OK stores. One is Delta, a brewer that also bottles Coca-Cola. Another is BAT Zimbabwe, whose cigarette brands include Newbury and Madison. This lopsided economy is a legacy of the collapse of Zimbabwe’s currency. Inflation reached an absurd 231,000,000% in the summer of 2008. Output measured in dollars had halved in barely a decade. A hundred-trillion-dollar note was made ready for circulation, but no sane tradesman would accept local banknotes. A ban on foreign-currency trading was lifted in January 2009. By then the American dollar had become Zimbabwe’s main currency, a position it still holds today. -

Political Leaders in Africa: Presidents, Patrons Or Profiteers?

Political Leaders in Africa: Presidents, Patrons or Profiteers? By Jo-Ansie van Wyk Occasional Paper Series: Volume 2, Number 1, 2007 The Occasional Paper Series is published by The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD). ACCORD is a non-governmental, non-aligned conflict resolution organisation based in Durban, South Africa. ACCORD is constituted as an education trust. Views expressed in this Occasional Paper are not necessarily those of ACCORD. While every attempt is made to ensure that the information published here is accurate, no responsibility is accepted for any loss or damage that may arise out of the reliance of any person upon any of the information this Occassional Paper contains. Copyright © ACCORD 2007 All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISSN 1608-3954 Unsolicited manuscripts may be submitted to: The Editor, Occasional Paper Series, c/o ACCORD, Private Bag X018, Umhlanga Rocks 4320, Durban, South Africa or email: [email protected] Manuscripts should be about 10 000 words in length. All references must be included. Abstract It is easy to experience a sense of déjà vu when analysing political lead- ership in Africa. The perception is that African leaders rule failed states that have acquired tags such as “corruptocracies”, “chaosocracies” or “terrorocracies”. Perspectives on political leadership in Africa vary from the “criminalisation” of the state to political leadership as “dispensing patrimony”, the “recycling” of elites and the use of state power and resources to consolidate political and economic power. -

African Union Election Observation Mission Report: Zimbabwe 2013

AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION REPORT OF AFRICAN UNION ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION TO THE 31 JULY 2013 HARMONISED ELECTIONS IN THE REPUBLIC OF ZIMBABWE DISTRIBUTED BY VERITAS Veritas makes every effort to ensure the provision of reliable information, but cannot take legal responsibility for information supplied. African Union Election Observation Mission Report: Zimbabwe 2013 CONTENTS List of Abbreviations ........................................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 3 II. OBJECTIVE AND METHODOLOGY OF THE MISSION ..................................................... 3 Objective ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Methodology .................................................................................................................................. 3 III. BACKGROUND TO THE 31 JULY 2013 ELECTIONS ...................................................... 5 IV. LEGAL CONTEXT ................................................................................................................ 9 The Constitution ............................................................................................................................. 9 The Zimbabwe Electoral Commission Act .................................................................................... 9 Political Parties -

The Mortal Remains: Succession and the Zanu Pf Body Politic

THE MORTAL REMAINS: SUCCESSION AND THE ZANU PF BODY POLITIC Report produced for the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum by the Research and Advocacy Unit [RAU] 14th July, 2014 1 CONTENTS Page No. Foreword 3 Succession and the Constitution 5 The New Constitution 5 The genealogy of the provisions 6 The presently effective law 7 Problems with the provisions 8 The ZANU PF Party Constitution 10 The Structure of ZANU PF 10 Elected Bodies 10 Administrative and Coordinating Bodies 13 Consultative For a 16 ZANU PF Succession Process in Practice 23 The Fault Lines 23 The Military Factor 24 Early Manoeuvring 25 The Tsholotsho Saga 26 The Dissolution of the DCCs 29 The Power of the Politburo 29 The Powers of the President 30 The Congress of 2009 32 The Provincial Executive Committee Elections of 2013 34 Conclusions 45 Annexures Annexure A: Provincial Co-ordinating Committee 47 Annexure B : History of the ZANU PF Presidium 51 2 Foreword* The somewhat provocative title of this report conceals an extremely serious issue with Zimbabwean politics. The theme of succession, both of the State Presidency and the leadership of ZANU PF, increasingly bedevils all matters relating to the political stability of Zimbabwe and any form of transition to democracy. The constitutional issues related to the death (or infirmity) of the President have been dealt with in several reports by the Research and Advocacy Unit (RAU). If ZANU PF is to select the nominee to replace Robert Mugabe, as the state constitution presently requires, several problems need to be considered. The ZANU PF nominee ought to be selected in terms of the ZANU PF constitution.