The Vatican Secret Archives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Guide Vatican City

Information Guide Vatican City A guide to information sources on the Vatican City State and the Holy See. Contents Information sources in the ESO database .......................................................... 2 General information ........................................................................................ 2 Culture and language information..................................................................... 2 Defence and security information ..................................................................... 2 Economic information ..................................................................................... 3 Education information ..................................................................................... 3 Employment information ................................................................................. 3 European policies and relations with the European Union .................................... 3 Geographic information and maps .................................................................... 3 Health information ......................................................................................... 3 Human rights information ................................................................................ 4 Intellectual property information ...................................................................... 4 Justice and home affairs information................................................................. 4 Media information ......................................................................................... -

The Holy See

The Holy See I GENERAL NORMS Notion of Roman Curia Art. 1 — The Roman Curia is the complex of dicasteries and institutes which help the Roman Pontiff in the exercise of his supreme pastoral office for the good and service of the whole Church and of the particular Churches. It thus strengthens the unity of the faith and the communion of the people of God and promotes the mission proper to the Church in the world. Structure of the Dicasteries Art. 2 — § 1. By the word "dicasteries" are understood the Secretariat of State, Congregations, Tribunals, Councils and Offices, namely the Apostolic Camera, the Administration of the Patrimony of the Apostolic See, and the Prefecture for the Economic Affairs of the Holy See. § 2. The dicasteries are juridically equal among themselves. § 3. Among the institutes of the Roman Curia are the Prefecture of the Papal Household and the Office for the Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff. Art. 3 — § 1. Unless they have a different structure in virtue of their specific nature or some special law, the dicasteries are composed of the cardinal prefect or the presiding archbishop, a body of cardinals and of some bishops, assisted by a secretary, consultors, senior administrators, and a suitable number of officials. § 2. According to the specific nature of certain dicasteries, clerics and other faithful can be added to the body of cardinals and bishops. § 3. Strictly speaking, the members of a congregation are the cardinals and the bishops. 2 Art. 4. — The prefect or president acts as moderator of the dicastery, directs it and acts in its name. -

The Holy See (Including Vatican City State)

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE EVALUATION OF ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING MEASURES AND THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM (MONEYVAL) MONEYVAL(2012)17 Mutual Evaluation Report Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism THE HOLY SEE (INCLUDING VATICAN CITY STATE) 4 July 2012 The Holy See (including Vatican City State) is evaluated by MONEYVAL pursuant to Resolution CM/Res(2011)5 of the Committee of Ministers of 6 April 2011. This evaluation was conducted by MONEYVAL and the report was adopted as a third round mutual evaluation report at its 39 th Plenary (Strasbourg, 2-6 July 2012). © [2012] Committee of experts on the evaluation of anti-money laundering measures and the financing of terrorism (MONEYVAL). All rights reserved. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. For any use for commercial purposes, no part of this publication may be translated, reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic (CD-Rom, Internet, etc) or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the MONEYVAL Secretariat, Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law, Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg or [email protected] ). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PREFACE AND SCOPE OF EVALUATION............................................................................................ 5 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................... -

Patronage and Dynasty

PATRONAGE AND DYNASTY Habent sua fata libelli SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES SERIES General Editor MICHAEL WOLFE Pennsylvania State University–Altoona EDITORIAL BOARD OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES ELAINE BEILIN HELEN NADER Framingham State College University of Arizona MIRIAM U. CHRISMAN CHARLES G. NAUERT University of Massachusetts, Emerita University of Missouri, Emeritus BARBARA B. DIEFENDORF MAX REINHART Boston University University of Georgia PAULA FINDLEN SHERYL E. REISS Stanford University Cornell University SCOTT H. HENDRIX ROBERT V. SCHNUCKER Princeton Theological Seminary Truman State University, Emeritus JANE CAMPBELL HUTCHISON NICHOLAS TERPSTRA University of Wisconsin–Madison University of Toronto ROBERT M. KINGDON MARGO TODD University of Wisconsin, Emeritus University of Pennsylvania MARY B. MCKINLEY MERRY WIESNER-HANKS University of Virginia University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Copyright 2007 by Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri All rights reserved. Published 2007. Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies Series, volume 77 tsup.truman.edu Cover illustration: Melozzo da Forlì, The Founding of the Vatican Library: Sixtus IV and Members of His Family with Bartolomeo Platina, 1477–78. Formerly in the Vatican Library, now Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana. Photo courtesy of the Pinacoteca Vaticana. Cover and title page design: Shaun Hoffeditz Type: Perpetua, Adobe Systems Inc, The Monotype Corp. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patronage and dynasty : the rise of the della Rovere in Renaissance Italy / edited by Ian F. Verstegen. p. cm. — (Sixteenth century essays & studies ; v. 77) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-931112-60-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-931112-60-6 (alk. paper) 1. -

A. Brief Overview of the Administrative History of the Holy See

A. Brief Overview of the Administrative History of the Holy See The historical documentation generated by the Holy See over the course of its history constitutes one of the most important sources for research on the history of Christianity, the history of the evolution of the modern state, the history of Western culture and institutions, the history of exploration and colonization, and much more. Though important, it has been difficult to grasp the extent of this documentation. This guide represents the first attempt to describe in a single work the totality of historical documentation that might properly be considered Vatican archives. Although there are Vatican archival records in a number of repositories that have been included in this publication, this guide is designed primarily to provide useful information to English-speaking scholars who have an interest in using that portion of the papal archives housed in the Vatican Archives or Archivio Segreto Vaticano (ASV). As explained more fully below, it the result of a project conducted by archivists and historians affiliated with the University of Michigan. The project, initiated at the request of the prefect of the ASV, focused on using modem computer database technology to present information in a standardized format on surviving documentation generated by the Holy See. This documentation is housed principally in the ASV but is also found in a variety of other repositories. This guide is, in essence, the final report of the results of this project. What follows is a complete printout of the database that was constructed. The database structure used in compiling the information was predicated on principles that form the basis for the organization of the archives of most modem state bureaucracies (e.g., provenance). -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC LETTER ISSUED MOTU PROPRIO NORMAS NONNULLAS OF THE SUPREME PONTIFF BENEDICT XVI ON CERTAIN MODIFICATIONS TO THE NORMS GOVERNING THE ELECTION OF THE ROMAN PONTIFF With the Apostolic Letter De Aliquibus Mutationibus in Normis de Electione Romani Pontificis, issued Motu Proprio in Rome on 11 June 2007, the third year of my Pontificate, I established certain norms which, by abrogating those laid down in No. 75 of the Apostolic Constitution Universi Dominici Gregis, promulgated on 22 February 1996 by my Predecessor Blessed John Paul II, reinstated the traditional norm whereby a majority vote of two thirds of the Cardinal electors present is always necessary for the valid election of a Roman Pontiff.Given the importance of ensuring that the entire process of electing the Roman Pontiff is carried out in the best possible way at every level, especially with regard to the sound interpretation and enactment of certain provisions, I hereby establish and decree that several norms of the Apostolic Constitution Universi Dominici Gregis, as well as the changes which I myself introduced in the aforementioned Apostolic Letter, are to be replaced by the following norms:No. 35. "No Cardinal elector can be excluded from active or passive voice in the election of the Supreme Pontiff, for any reason or pretext, with due regard for the provisions of Nos. 40 and 75 of this Constitution."No. 37. "I furthermore decree that, from the moment when the Apostolic See is lawfully vacant, fifteen full days must elapse before the Conclave begins, in order to await those who are absent; nonetheless, the College of Cardinals is granted the faculty to move forward the start of the Conclave if it is clear that all the Cardinal electors are present; they can also defer, for serious reasons, the beginning of the election for a few days more. -

New Vatican Library Website Aims to Serve Scholars, Entice Curious

New Vatican Library website aims to serve scholars, entice curious VATICAN CITY (CNS) — The Vatican Library has revamped its website to serve scholars better and facilitate navigation for the curious. “Because of the pandemic, physical presence has become more difficult and, therefore, the website aims to be a place for welcoming, collaboration and openness,” Msgr. Cesare Pasini, the library’s prefect, told Vatican News July 22. With a fresh look, easier and more intuitive navigation, and greater online services for researchers, the updated site, www.vaticanlibrary.va, went live in mid-July, right when the library closed for the summer months. Along with many other Vatican institutions open to the public, the library had shut down during Italy’s nationwide lockdown, then reopened June 1 to limited numbers of scholars and with the required restrictions and safety measures to curb the spread of the coronavirus. Plans for the “restyling” ended up being especially opportune given the continued restrictions and that the pandemic in other parts of the world may be preventing other scholars from traveling to Italy to do research at the library. Some of the new features, the monsignor said, include more powerful and expanded search functions, and registered researchers can now easily ask staff questions and order digital reproductions of manuscripts, texts and other materials from the libraries collections. “We are the pope’s librarians,” he said, and every pope over the centuries has wanted the library to be open to the world. “That is why we want to truly be at the service of our visitors with a modern and up-to-date tool that immediately provides what people are searching for or even offers them something more,” he said. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC CONSTITUTION PASTOR BONUS JOHN PAUL, BISHOP SERVANT OF THE SERVANTS OF GOD FOR AN EVERLASTING MEMORIAL TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction I GENERAL NORMS Notion of Roman Curia (art. 1) Structure of the Dicasteries (arts. 2-10) Procedure (arts. 11-21) Meetings of Cardinals (arts. 22-23) Council of Cardinals for the Study of Organizational and Economic Questions of the Apostolic See (arts. 24-25) Relations with Particular Churches (arts. 26-27) Ad limina Visits (arts. 28-32) Pastoral Character of the Activity of the Roman Curia (arts. 33-35) Central Labour Office (art. 36) Regulations (arts. 37-38) II SECRETARIAT OF STATE (Arts. 39-47) 2 First Section (arts. 41-44) Second Section (arts. 45-47) III CONGREGATIONS Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (arts. 48-55) Congregation for the Oriental Churches (arts. 56-61) Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments (arts. 62-70) Congregation for the Causes of Saints (arts. 71-74) Congregation for Bishops (arts. 75-84) Pontifical Commission for Latin America (arts. 83-84) Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples (arts. 85-92) Congregation for the Clergy (arts. 93-104) Pontifical Commission Preserving the Patrimony of Art and History (arts. 99-104) Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and for Societies of Apostolic Life (arts. 105-111) Congregation of Seminaries and Educational Institutions (arts. 112-116) IV TRIBUNALS Apostolic Penitentiary (arts. 117-120) Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura (arts. 121-125) Tribunal of the Roman Rota (arts. 126-130) V PONTIFICAL COUNCILS Pontifical Council for the Laity (arts. -

Pdf (Accessed January 21, 2011)

Notes Introduction 1. Moon, a Presbyterian from North Korea, founded the Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity in Korea on May 1, 1954. 2. Benedict XVI, post- synodal apostolic exhortation Saramen- tum Caritatis (February 22, 2007), http://www.vatican.va/holy _father/benedict_xvi/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_ben-xvi _exh_20070222_sacramentum-caritatis_en.html (accessed January 26, 2011). 3. Patrician Friesen, Rose Hudson, and Elsie McGrath were subjects of a formal decree of excommunication by Archbishop Burke, now a Cardinal Prefect of the Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signa- tura (the Roman Catholic Church’s Supreme Court). Burke left St. Louis nearly immediately following his actions. See St. Louis Review, “Declaration of Excommunication of Patricia Friesen, Rose Hud- son, and Elsie McGrath,” March 12, 2008, http://stlouisreview .com/article/2008-03-12/declaration-0 (accessed February 8, 2011). Part I 1. S. L. Hansen, “Vatican Affirms Excommunication of Call to Action Members in Lincoln,” Catholic News Service (December 8, 2006), http://www.catholicnews.com/data/stories/cns/0606995.htm (accessed November 2, 2010). 2. Weakland had previously served in Rome as fifth Abbot Primate of the Benedictine Confederation (1967– 1977) and is now retired. See Rembert G. Weakland, A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church: Memoirs of a Catholic Archbishop (Grand Rapids, MI: W. B. Eerdmans, 2009). 3. Facts are from Bruskewitz’s curriculum vitae at http://www .dioceseoflincoln.org/Archives/about_curriculum-vitae.aspx (accessed February 10, 2011). 138 Notes to pages 4– 6 4. The office is now called Vicar General. 5. His principal consecrator was the late Daniel E. Sheehan, then Arch- bishop of Omaha; his co- consecrators were the late Leo J. -

The Secret Vatican Archives by FRANCIS J

The Secret Vatican Archives By FRANCIS J. WEBER* Chancery Archives Archdiocese of Los Angeles Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/27/1/63/2744560/aarc_27_1_6800776812016243.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 F all the relations between Europe and America that from time to time have been reflected in European archives, per- O haps the most continuous have been relations involving the Catholic Church. As one scholar has phrased it, "The records of that church are, therefore, organic archives for Canada and for the larger portion of the United States during their entire history."1 This author recently had occasion to work in the Archivio Segreto Vaticano in search of materials dealing with the history of the Catholic Church in California. And it was while searching through the numberless indexes that he realized that the precious collection has not been exploited by English-speaking scholars to any great extent. The following observations are limited to that part of the greater collection of Vatican Archives known as "secret" but the reader should not overlook the other holdings of the Vatican, which can only be mentioned here in passing. The Archivio Segreto Vaticano is really not "secret" at all, even though the archivist occasionally restricts the use of materials of a private nature (carattere riservato) "which cannot be given pub- licity for reasons of public interest, religious and social."2 Any serious scholar will be admitted upon addressing a written request to the Prefetto dell'Archivio Segreto Vaticano, Citta del Vaticano.3 Two small photographs of the petitioner are required along with a statement of his qualifications or letters of recommendation and a general description of the documentations he wishes to consult.4 The idea of grouping the archives of the various congregations or departments of the Holy See into one general collection had long been contemplated but it was Pope Paul V who actually initiated the archivio in 1611. -

Communication Bilancio 2020

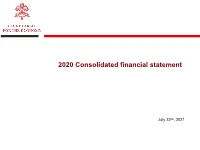

2020 Consolidated financial statement July 22nd, 2021 The Vatican and the Roman Curia are not the same. We are presenting ONLY the balance of the Roman Curia 2020 Total Vatican 2020 Consolidation Perimeter (Net Equity %) Income 248M€ Expenses 315M€ Net Equity 1.379M€ # of Entities 60 2 2 2020 Consolidated Financial Statement – Balance Sheet Variance vs COMMENTS M€ 2020 Actual 2019 Actual Actual 2019 Assets 2.203,2 2.154,0 49,2 ▪ Cash and Cash Equivalents (+148,4M€) – strategy to maintain as much liquidity as possible due to the Current Assets 1.186,3 949,5 236,8 uncertainties cause by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Cash and cash equivalents 521,3 372,9 148,4 Opposite impact in long term financial investments. Receivables (+83,5M€) – mainly due to a loan agreement Receivables 165,1 81,5 83,5 ▪ between APSA and SdS to refinance investment of 60SA Current Financial Investments 495,7 491,1 4,6 (London) at much better conditions (+127M€), partially offset by the collection of the credits to Papal Funds (30 Others 4,2 4,0 0,2 M€) and to CFIC (10 M€). Non - Current Assets 1.016,9 1.204,4 (187,6) ▪ Non current Financial Investments (-180,3M€) – due to Tangile and Intangible Assets 14,6 14,4 0,2 divestments on long term instruments to increase liquidity (see first point) and to decrease short term financial Investments Properties 618,5 625,9 (7,4) liabilities. Non - Current Financial Investments 383,8 564,1 (180,3) ▪ Current Financial Liabilities (-26,5M€) – driven by the Liabilities and Net Equity 2.203,2 2.154,0 49,2 repayment of APSA debt to Bambin Gesù Hospital (19 M€) and the net short term financial position of APSA versus Current Liabilities 467,5 489,2 (21,8) other Holy See’s depository entities. -

Vatican Library 2002 Report to CENL

Vatican Library 2002 Report to CENL 1. Management of the Library The Vatican Library is an Institution whose main task is research and the promotion of studies. That mission concretely leads to a specialization, determined by the treasures it preserves: the large collections of manuscripts. The major efforts of the management are actually concentrated on those treasures, with a precise action on the ancient documents and on the spaces where they are preserved. 2. Digital publications Jus Commune , reproduction in CD-Rom of several ancient printed law books (in coedition with “Sub Signo Stellae”) 3. Legislation According to the rules instituted by the “Law on the guardianship of the cultural goods” (25 July 2001), requesting the administrative inventory of all the cultural goods of the Holy See, the Library is finishing the work on its property, archival materials, manuscripts, and it will have soon another tool for the reference work, the General Inventory of non-catalogued manuscripts that will be in the future available on-line; it will certainly help the research work on our manuscripts. 4. Buildings Space is a big worry. The building is ancient and very difficult to make it be in accordance with the regulations in force; besides, the space available is absolutely insufficient. We have recently transferred the store of the Printing House out of Vatican City; the Vatican School of Library Science was also placed outside, in a beautiful building not far from St. Peter’s, and we hope to transfer soon, to be catalogued, a collection of 100,000 volumes (De Luca Collection).