Making Machines Learn. Applications of Cultural Analytics to the Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos Nº 337-338, Julio-Agosto 1978

CUADERNOS HISPANOAMERICANOS MADRID JULIO-AGOSTO 1978 337-338 CUADERNOS HISPANO AMERICANOS DIRECTOR JOSÉ ANTONIO MARAVALL JEFE DE REDACCIÓN FÉLIX GRANDE HAN DIRIGIDO CON ANTERIORIDAD ESTA REVISTA PEDRO LAIN ENTRALGO LUIS ROSALES DIRECCIÓN, SECRETARIA LITERARIA Y ADMINISTRACIÓN Centro Iberoamericano de Cooperación Avenida de los Reyes Católicos Teléfono 244 06 00 MADRID CUADERNOS HISPANOAMERICANOS Revista mensual de Cultura Hispánica Depósito legal: M 3875/1958 DIRECTOR JOSÉ ANTONIO MARAVALL JEFE DE REDACCIÓN FÉLIX GRANDE 337-338 DIRECCIÓN, ADMINISTRACIÓN Y SECRETARIA Centro Iberoamericano de Cooperación Avda. de los Reyes Católicos Teléfono 244 06 00 MADRID INDICE NUMEROS 337-338 (JULIO-AGOSTO 1978) HOMENAJE A CAMILO JOSE CELA Páginas JOSE GARCIA NIETO: Carta mediterránea a Camilo José Cela ... 5 FERNANDO QUIÑONES: Lo de Casasana 13 HORACIO SALAS: San Camilo 1936-Madrid. San Rómulo 1976-Bue- nos Aires 17 PEDRO LAIN ENTRALGO: Carta de un pedantón a un vagabundo por tierras de España 20 JOSE MARIA MARTINEZ CACHERO: El septenio 1940-1946 en la bi bliografia de Camilo José Cela : 34 ROBERT KIRSNER: Camilo José Cela: la conciencia literaria de su sociedad • 51 PAUL ILIE: La lectura del «vagabundaje» de Cela en la época pos franquista 61 EDMOND VANDERCAMMEN: Cinco ejemplos del ímpetu narrativo de Camilo José Cela 81 JUAN MARIA MARIN MARTINEZ: Sentido último de «La familia de Píí ^C'tirii DtJ3tt&¡> Qn JESUS SANCHEZ LOBATO: La adjetivación "en «La familia de Pas cual Duarte» 99 GONZALO SOBEJANO: «La Colmena»: olor a miseria 113 VICENTE CABRERA: En busca de tres personajes perdidos en «La Colmena» 127 D. W. McPHEETERS: Tremendismo y casticismo 137 CARMEN CONDE: Camilo José Cela: «Viaje a la Alcarria» 147 CHARLES V. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Brad a Mante

B radA mante Revista de Letras, 1 (2020) Hablo de aquella célebre doncella la cual abatió en duelo a Sacripante. Hija del duque Amón y de Beatriz, era muy digna hermana de Rinaldo. Con su audacia y valor asombra a Carlos y Francia entera aplaude su coraje, que en más de una ocasión quedó probado, en todo comparable al de su hermano. Orlando furioso II, 31 B radA mante Revista de Letras, 1 (2020) | issn 2695-9151 BradAmante. Revista de Letras Dirección Basilio Rodríguez Cañada - Grupo Editorial Sial Pigmalión José Ramón Trujillo - Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Comité científico internacional M.ª José Alonso Veloso - Universidade de Santiago de Compostela Carlos Alvar - Université de Genève (Suiza) José Luis Bernal Salgado - Universidad de Extremadura Justo Bolekia Boleká - Universidad de Salamanca Rafael Bonilla Cerezo - Universidad de Córdoba Randi Lise Davenport - Universidad de Tromsø (Noruega) J. Ignacio Díez - Universidad Complutense de Madrid Ángel Gómez Moreno - Universidad Complutense de Madrid Fernando González García - Universidad de Salamanca Francisco Gutiérrez Carbajo - Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia Javier Huerta Calvo - Universidad Complutense de Madrid José Manuel Lucía Megías - Universidad Complutense de Madrid Karla Xiomara Luna Mariscal - El Colegio de México (México) Ridha Mami - Université La Manouba (Túnez) Fabio Martínez - Universidad del Valle (Colombia) Carmiña Navia Velasco - Universidad del Valle (Colombia) José María Paz Gago - Universidade da Coruña José Antonio Pascual Rodríguez - Real Academia -

The New Urban Success: How Culture Pays

The New Urban Success: How Culture Pays DESISLAVA HRISTOVA, Cambridge University, Cambridge, UK LUCA MARIA AIELLO, Nokia Bell Labs, Cambridge, UK DANIELE QUERCIA, Nokia Bell Labs, Cambridge, UK Urban economists have put forward the idea that cities that are culturally interesting tend to attract “the creative class” and, as a result, end up being economically successful. Yet it is still unclear how economic and cultural dynamics mutually influence each other. By contrast, that has been extensively studied inthecase of individuals. Over decades, the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu showed that people’s success and their positions in society mainly depend on how much they can spend (their economic capital) and what their interests are (their cultural capital). For the first time, we adapt Bourdieu’s framework to the city context. We operationalize a neighborhood’s cultural capital in terms of the cultural interests that pictures geo-referenced 27 in the neighborhood tend to express. This is made possible by the mining of what users of the photo-sharing site of Flickr have posted in the cities of London and New York over 5 years. In so doing, we are able to show that economic capital alone does not explain urban development. The combination of cultural capital and economic capital, instead, is more indicative of neighborhood growth in terms of house prices and improvements of socio-economic conditions. Culture pays, but only up to a point as it comes with one of the most vexing urban challenges: that of gentrification. Additional Key Words and Phrases: culture, cultural capital, Pierre Bourdieu, hysteresis effect, Flickr Original paper published on Frontiers: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2018.00027 1 INTRODUCTION The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu argued that we all possess certain forms of social capital. -

Hybridizing Learning, Performing Interdisciplinarity: Teaching Digitally in a Posthuman Age

Hybridizing Learning, Performing Interdisciplinarity: Teaching Digitally in a Posthuman Age Elizabeth Losh University of California, Irvine Humanities Instructional Building 188 U.C. Irvine, Irvine, CA 92697 USA 01-949-824-8130 [email protected] ABSTRACT students and learners perform knowledge work that appeals to the This paper discusses how Southern California serves as a site of broader public. regional advantage for developing new hybridized forms of Although many examples of interdisciplinary pedagogy come interdisciplinary pedagogy, because networks of educators in from studio art or computer science programs that combine art higher education are connected by local hubs created by and science paradigms of technê rather than epistêmê, there are intercampus working groups, multidisciplinary institutes funded also a number of notable local efforts in the “digital humanities” by government agencies, and philanthropic organizations that that bring students and teachers from many departments and fund projects that encourage implementation of instructional majors together from disciplines traditionally associated with print technologies that radically re-imagine curricula, student culture and the classical trivium. interaction, and the spaces and interfaces of learning. It describes ten trends in interdisciplinary pedagogy and case studies from For example, archeology and architecture students have explored four college campuses that show how these trends are being a life-sized computer-generated 3-D model of ancient Rome in a manifested. -

Catalogoqueleopedrodevaldivia40.Pdf

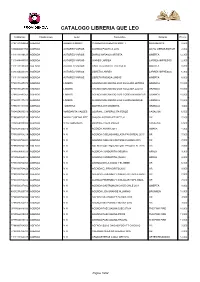

CATALOGO LIBRERIA QUE LEO CodBarras Clasificacion Autor Titulo Libro Editorial Precio 7798141020454 AGENDA ALBERTO MONTT CUADERNO ALBERTO MONTT MONOBLOCK 8,500 1000000001709 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS AGENDA POLITICA 2012 OCHO LIBROS EDITOR 2,900 1111111199121 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS DIARIO NARANJA ARTISTA OMERTA 12,300 1111444445551 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS IMANES LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 2,900 1111111198988 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA GRANATE CALCULO OMERTA 8,200 3333344443330 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 6,900 1111111198995 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA ROSADA LINEAS OMERTA 8,500 7798071447376 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LETRAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447390 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LLUVIA GRANICA 10,000 7798071447352 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BANDERAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447338 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BOSQUE GRANICA 10,000 7798071444399 AGENDA . MAITENA MAITENA 007 MAGENTA GRANICA 1,000 7804654930019 AGENDA MARGARITA VALDES JOURNAL, CAPERUCITA FEROZ VASALISA 6,500 7798083702128 AGENDA MARIA EUGENIA PITE CHUICK AGENDA PERPETUA VR 7,200 7804654930002 AGENDA NICO GONZALES JOURNAL PIZZA PALIZA VASALISA 6,500 7804634920016 AGENDA N N AGENDA AMAKA 2011 AMAKA 4,900 7798083704214 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO ANILLADA PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704221 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE FLORES 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704238 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 9789568069025 AGENDA N N AGENDA CONDORITO (NEGRA) ORIGO 9,900 9789568069032 AGENDA -

What Is Cultural History? Free

FREE WHAT IS CULTURAL HISTORY? PDF Peter Burke | 168 pages | 09 Sep 2008 | Polity Press | 9780745644103 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom What is cultural heritage? – Smarthistory Programs Ph. Cultural History Cultural history brings to life a past time and place. In this search, cultural historians study beliefs and ideas, much as What is Cultural History? historians do. In addition to the writings of intellectual elites, they consider the notions sometimes unwritten of the less privileged and less educated. These are reflected in the products of deliberately artistic culture, but also include the objects and experiences of everyday life, such as clothing or cuisine. In this sense, our instincts, thoughts, and acts have an ancestry which cultural history can illuminate and examine critically. Historians of culture at Yale study all these aspects of the past in their global interconnectedness, and explore how they relate to our many understandings of our varied presents. Cultural history is an effort to inhabit the minds of the people of different worlds. This journey is, like great literature, thrilling in itself. It is also invaluable for rethinking our own historical moment. Like the air we breathe, the cultural context that shapes our understanding of the world is often invisible for those who are surrounded by it; cultural history What is Cultural History? us to take a step back, and recognize that some of what we take for granted is remarkable, and that some of what we have thought immutable and What is Cultural History? is contingent and open to change. Studying how mental categories have shifted inspires us to What is Cultural History? how our own cultures and societies can evolve, and to ask what we can do as individuals to shape that process. -

PDF Download Intercultural Communication for Global

INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION FOR GLOBAL ENGAGEMENT 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Regina Williams Davis | 9781465277664 | | | | | Intercultural Communication for Global Engagement 1st edition PDF Book Resilience, on the other hand, includes having an internal locus of control, persistence, tolerance for ambiguity, and resourcefulness. This textbook is suitable for the following courses: Communication and Intercultural Communication. Along with these attributes, verbal communication is also accompanied with non-verbal cues. Create lists, bibliographies and reviews: or. Linked Data More info about Linked Data. A critical analysis of intercultural communication in engineering education". Cross-cultural business communication is very helpful in building cultural intelligence through coaching and training in cross-cultural communication management and facilitation, cross-cultural negotiation, multicultural conflict resolution, customer service, business and organizational communication. September Lewis Value personal and cultural. Inquiry, as the first step of the Intercultural Praxis Model, is an overall interest in learning about and understanding individuals with different cultural backgrounds and world- views, while challenging one's own perceptions. Need assistance in supplementing your quizzes and tests? However, when the receiver of the message is a person from a different culture, the receiver uses information from his or her culture to interpret the message. Acculturation Cultural appropriation Cultural area Cultural artifact Cultural -

What Is Cultural Value?

Understanding the Changing Cultural Value of the BBC World Service Interim Report The Open University th 26 March 2014 Table of Contents The Cultural Value Project: Executive Summary ................................................................. 3 The Project Team .............................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 4 Going Digital with Legacy .................................................................................................. 5 The Cultural Value Project................................................................................................. 6 The Changing Cultural Value of the BBC World Service: Research Questions ...................... 7 Which publics does and should the WS serve? .......................................................................... 7 What is distinctive about WS? .................................................................................................. 7 Why Now?........................................................................................................................ 8 What is Cultural Value? ..................................................................................................... 9 Is international news ‘culture’? ................................................................................................ 9 Why ”Cultural Value”? ............................................................................................................ -

CV Alberto Acerbi

Alberto Acerbi Gaskell Building 206 email: [email protected] Brunel University London web: acerbialberto.com Uxbridge, UB8 3PH GitHub: albertoacerbi United Kingdom twitter: @acerbialberto phone: +44 (0)1895 265925 Current position Lecturer / Assistant professor Centre for Culture and Evolution, Department of Psychology, Brunel University London 2019 - current Areas of specialization Cultural evolution, Cognitive anthropology, digital media, individual-based modelling, cultural analytics. Education PhD, Anthropology, University of Siena (Italy) November 2007 MA, Philosophy (cum laude), University of Siena (Italy) October 2002 Previous positions School of Innovation Science, Eindhoven University of Technology 2015 - 2019 Researcher Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, Bristol University (UK) 2013 - 2014 Newton Research Fellow Centre for the study of cultural evolution 2008 - 2012 Stockholm University (Sweden) & University of Bologna (Italy) Post-doctoral researcher Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig (Germany) 2007 - 2008 Post-doctoral researcher Institute of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies, CNR, Rome (Italy) 2004 - 2007 Research assistant Last updated: August 14, 2021 CV Alberto Acerbi Publications BOOKS: 1. Acerbi A (2020), Cultural Evolution in the Digital Age, Oxford: Oxford University Press. - translation in Arabic, Arab Scientifc Publishers, Inc., forthcoming 2. Acerbi A, Mesoudi A, Smolla M (2020), Individual-based models of cultural evolution. A step-by-step guide using R, doi:110.31219/osf.io/32v6a. Open access manual, available at: https://acerbialberto.com/IBM- cultevo PREPRINTS: 1. Acerbi A, Sacco PL (2021), The self-control vs. self-indulgence dilemma: A culturomic analysis of 20th century trends, available at: https://osf.io/xgqt5/ 2. Acerbi A (2021), From storytelling to Facebook. Content biases when retelling or sharing a story, available at: https://osf.io/br56y/ 3. -

Measuring the Effects of Bias in Training Data for Literary Classification

Measuring the Effects of Bias in Training Data for Literary Classification Sunyam Bagga Andrew Piper .txtLAB Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures McGill University McGill University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Downstream effects of biased training data have become a major concern of the NLP community. How this may impact the automated curation and annotation of cultural heritage material is cur- rently not well known. In this work, we create an experimental framework to measure the effects of different types of stylistic and social bias within training data for the purposes of literary clas- sification, as one important subclass of cultural material. Because historical collections are often sparsely annotated, much like our knowledge of history is incomplete, researchers often can- not know the underlying distributions of different document types and their various sub-classes. This means that bias is likely to be an intrinsic feature of training data when it comes to cultural heritage material. Our aim in this study is to investigate which classification methods may help mitigate the effects of different types of bias within curated samples of training data. We find that machine learning techniques such as BERT or SVM are robust against reproducing certain kinds of social and stylistic bias within our test data, except in the most extreme cases. We hope that this work will spur further research into the potential effects of bias within training data for other cultural heritage material beyond the study of literature. 1 Introduction One of the challenges facing researchers working with cultural heritage data is the difficulty of producing historically representative samples of data (Bode, 2020). -

Managing Facilitation in Cross-Cultural Contexts March 2014

Managing Facilitation in Cross-Cultural Contexts March 2014 Managing Facilitation in Cross-Cultural Contexts: The Application of National Cultural Dimensions to Groups in Learning Organisations Matthew Jelavic, Dawn Salter Durham College Authors’ Contact Information Matthew Jelavic Durham College 2000 Simcoe Street North Oshawa, Ontario, L1H 7K4 phone: 905-721-2000 email: [email protected] Dawn Salter email: [email protected] Abstract: This paper provides an evaluation of the literature pertaining to national culture as it relates to pedagogy and the management of facilitation processes within groups in learning organisations. National culture plays a pivotal role influencing the cognitive processes of individuals and their comfort levels with various methods of facilitation management. By incorporating cultural analytics into the preparation of cross-cultural facilitative processes, facilitators can ensure management methods meet the unique needs of the participants. Key Words: Facilitation management, pedagogy, learning organisations, groups, training, national culture. Introduction The following paper explores a pedagogical approach to managing facilitation in relation to the theoretical concepts of national culture as originally developed by Geert Hofstede in his book Culture’s Consequences (Hofstede, 1980). Facilitation management is considered a core competency for those seeking to create and manage learning groups effectively and thus has become a popular pedagogical approach in the field of adult education