To Purify the Bar: a Constitutional Approach to Non-Professional Misconduct

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judicial Acquiescence in the Forfeiture of Constitutional Rights Through Expansion of the Conditioned Privilege Doctrine

Indiana Law Journal Volume 28 Issue 4 Article 4 Summer 1953 Judicial Acquiescence in the Forfeiture of Constitutional Rights through Expansion of the Conditioned Privilege Doctrine Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation (1953) "Judicial Acquiescence in the Forfeiture of Constitutional Rights through Expansion of the Conditioned Privilege Doctrine," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 28 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol28/iss4/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INDIANA LAW JOURNAL from detruction by Communism, there is vital need to salvage consti- tutionally guaranteed rights from annihilation by these same efforts. Both courts and legislatures should re-examine the Communist threat and should then determine whether recent laws do themselves present more of a threat to our freedom than does subversion. JUDICIAL ACQUIESCENCE IN THE FORFEITURE OF CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS THROUGH EXPANSION OF THE CONDITIONED PRIVILEGE DOCTRINE Mr. Justice Douglas, dissenting in Adler v. Board of Education of the City of New York, declared: "I have not been able to accept the recent doctrine that a citizen who enters the public service can be forced to sacrifice his civil rights. I cannot for example find in our constitutional scheme the power of the state to place its employees in the category of second class citizens by denying them freedom of thought and expres- sion."' It is both surprising and noteworthy that Mr. -

Entanglements Between Church and State in America

2~ CHAPTER SEVEN THE SUPREME COURT AS A GUARDIAN The Supreme Court addressed the great issues of religious faith and practice only rarely during its first century of operation. It usually let state law and local custom prevail except where some larger constitutional value was at stake. Even in the first decades of this century, the Court was circumspect in its treatment of religious controversies. Most of the cases that directly implicated the religion clauses in these early years involved members of religious minorities, particularly Mormons and Catholics. The Court weighed the religious issues~~which often played only a minor part in the Court's final determination~-on the scales of a generalized Christian standard of personal morality and public expression without explicitly defining religion. Specific cultic practices that threatened to disturb public peace and order simply fell outside the pale of free exercise protections. This early period is covered in Chapter Seven. The justices began to negotiate more precise constitutional metes and bounds in earnest during the 1940s after the Court decided that the Fourteenth Amendment made the free exercise and establishment provisions of the First Amendment applicable to the states and localities. A rough sketch of acceptable practices and legitimate regulations began to emerge. With a few exceptions, such as the polygamy cases, the Court had until then carefully avoided taking an activist role in the area of 259 religion. But in its efforts to correct some definite abuses and constitutional problems in the local regulation of religious proselytism, the Court perhaps needlessly broadened its jurisdiction, leaving it open to a myriad of competing claims and counterclaims. -

Admission to the Bar: a Constitutional Analysis

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Issue 3 - April 1981 Article 4 4-1981 Admission to the Bar: A Constitutional Analysis Ben C. Adams Edward H. Benton David A. Beyer Harrison L. Marshall, Jr. Carter R. Todd See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Ben C. Adams; Edward H. Benton; David A. Beyer; Harrison L. Marshall, Jr.; Carter R. Todd; and Jane G. Allen Special Projects Editor, Admission to the Bar: A Constitutional Analysis, 34 Vanderbilt Law Review 655 (1981) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol34/iss3/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Admission to the Bar: A Constitutional Analysis Authors Ben C. Adams; Edward H. Benton; David A. Beyer; Harrison L. Marshall, Jr.; Carter R. Todd; and Jane G. Allen Special Projects Editor This note is available in Vanderbilt Law Review: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol34/iss3/4 SPECIAL PROJECT Admission to the Bar: A Constitutional Analysis I. INTRODUCTION .................................... 657 II. PERMANENT ADMISSION TO THE BAR ................. 661 A. Good Moral Character ....................... 664 1. Due Process--The Analytical Framework... 666 (a) Patterns of Conduct Resulting in a Finding of Bad Moral Character:Due Process Review of Individual Deter- minations ........................ -

First Amendment

FIRST AMENDMENT RELIGION AND FREE EXPRESSION CONTENTS Page Religion ....................................................................................................................................... 1063 An Overview ....................................................................................................................... 1063 Scholarly Commentary ................................................................................................ 1064 Court Tests Applied to Legislation Affecting Religion ............................................. 1066 Government Neutrality in Religious Disputes ......................................................... 1070 Establishment of Religion .................................................................................................. 1072 Financial Assistance to Church-Related Institutions ............................................... 1073 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Released Time ...... 1093 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Prayers and Bible Reading ..................................................................................................................... 1094 Governmental Encouragement of Religion in Public Schools: Curriculum Restriction ................................................................................................................ 1098 Access of Religious Groups to Public Property ......................................................... 1098 Tax Exemptions of Religious Property ..................................................................... -

Constitutional Law - Due Process - Denial of Admission to the Bar Based on Unwarranted Inferences of Bad Moral Character

Michigan Law Review Volume 56 Issue 3 1958 Constitutional Law - Due Process - Denial of Admission to the Bar Based on Unwarranted Inferences of Bad Moral Character Jerome B. Libin University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Fourteenth Amendment Commons, Jurisdiction Commons, Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Jerome B. Libin, Constitutional Law - Due Process - Denial of Admission to the Bar Based on Unwarranted Inferences of Bad Moral Character, 56 MICH. L. REV. 415 (1958). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol56/iss3/5 This Response or Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-DUE PROCESS-DENIAL OF ADMISSION TO THE BAR BASED ON UNWARRANTED INFERENCES OF BAD MORAL CHARACTER-Power over admission to the bar has long been vest- 416 MICHIGAN LAW REVIEW [ Vol. 56 ed in the judiciary of each state. While the legislature may pre scribe certain standards, the state court alone is responsible for the determination of those qualified for the practice of law with in its jurisdiction. The application of these standards often de mands the exercise of meticulous judgment by the court in reaching its conclusion as to an applicant's fitness. -

Consequences of Supreme Court Decisions Upholding Individual Constitutional Rights

Michigan Law Review Volume 83 Issue 1 1984 Consequences of Supreme Court Decisions Upholding individual Constitutional Rights Jesse H. Choper University of California, Berkeley Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Jesse H. Choper, Consequences of Supreme Court Decisions Upholding individual Constitutional Rights, 83 MICH. L. REV. 1 (1984). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol83/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSEQUENCES OF SUPREME COURT DECISIONS UPHOLDING INDIVIDUAL CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS Jesse H. Choper* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .•••...••••••••.••••.••• •'. • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • • . 4 I. COMPLEXITIES OF MEASUREMENT • • • • . • • . • • . • • • • . 7 II. SOME ILLUSTRATIONS PRIOR TO 1935.................. 12 A. The Post-Civil War Period . 12 B. The "Lochner" Era . 13 III. THE HUGHES, STONE, AND VINSON COURTS........... 14 A. Rights of the Accused. 15 1. Coerced Confessions . 15 2. Appointed Counsel . 15 a. Federal prosecutions . 15 b. State prosecutions. 16 B. Free Speech: Labor Picketing . 17 C. Religious Freedom: Jehovah's Witnesses............. 18 D. Company Towns................................... 19 E. Racial Discrimination . 19 1. Voting......................................... 19 2. Housing....................................... 21 3. Education . 22 IV. THE WARREN COURT................................... 25 A. Racial Separation . 25 1. Segregation . 25 2. Miscegenation . 28 * Dean and Professor of Law, University of California, Berkeley. -

A Passion for Justice

Touro Law Review Volume 26 Number 2 Article 3 September 2012 A Passion for Justice Charles A. Reich Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Judges Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Reich, Charles A. (2012) "A Passion for Justice," Touro Law Review: Vol. 26 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol26/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Passion for Justice Cover Page Footnote 26-2 This article is available in Touro Law Review: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol26/iss2/3 Reich: A Passion for Justice A PASSION FOR JUSTICE Charles A. Reich* Justice Hugo L. Black and CharlesReich February 27, 1966 * Copyright C 2010 by Charles A Reich. A.B. Oberlin 1949, LL.B. Yale 1952. This Article began with a letter from Professor Todd Peppers of Roanoke College, who was preparing a book of experiences by Supreme Court law clerks. He asked me if I would contribute a description of my year with Justice Black, and I agreed. Later it was Professor Peppers who suggested the Post-Clerkship section. I started with what I expected to be a short piece in the spring of 2009. Greg Marriner worked with me on every draft from the earliest effort to the final page proof. -

The “Communist Question” Cases Reconsidered

The “Communist Question” Cases Reconsidered Daniel C. Auten Moundsville, WV B.A., West Virginia University, 2015 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Virginia May 2018 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 I. PRELUDE: “OFFICERS OF THE COURT,” THE FIRST BAR ADMISSION CASE, AND THE LOOMING THREAT OF COMMUNISM ..............................................................................4 II. BACKGROUND: THE MCCARTHY ERA .........................................................................11 III. THE BAR AND COMMUNISM .........................................................................................16 A. The Internal Regulation of the Bar: The Proposed “Loyalty Oath” and the Communist Resolutions ..................................................................................................................19 B. The Bar’s External Relationships: Criticism of the Supreme Court and The Bar’s Place in the Legal System ...........................................................................................31 IV. BAR ADMISSION AND THE “COMMUNIST QUESTION” ....................................................40 A. Konigsberg I & II, Schware, and Anastaplo ................................................................41 B. Baird, Stolar, & Wadmond .........................................................................................44 -

THE SUPREME COURT UNDER FIRE Louis H. Pollak

Role of the Supreme Court Symposium, No. 7 THE SUPREME COURT UNDER FIRE Louis H. Pollak- I "NOT SINCE THE Nine Old Men shot down Franklin Roosevelt's Blue Eagle in 1935 has the Supreme Court been the center of such general commo- tion... ."1 The reasons are plain. In the closing weeks of the October term, 1956, the Court handed down a spate of opinions boldly reasserting its authority to review and overturn federal and state action-judicial, legis- lative and executive--of the highest sensitivity: the Court upset Smith Act convictions; 2 curbed federal3 and state4 legislative investigations of "un-American" or "subversive" activity; limited state authority to refuse admission to the bar on the basis of alleged past Communist belief;5 vindi- cated the exercise of the privilege against self-incrimination by one charged with conspiring to defraud the government of taxes; 6 protected the right of a fugitive Communist and his abettors to be free from unlawful search and seizure;7 required that a defendant charged with filing a false non-Commu- nist affidavit be furnished access to government witnesses' reports to the FBI;8 cast grave doubt on federal authority to court-martial civilian depend- ents of American military personnel stationed abroad;9 and gave renewed evidence that the principles declared in the School Segregation Cases'0 would not be compromised." * Associate Professor of Law, Yale Law School. The writer wishes to acknowledge, with gratitude, the assistance of Louise E. Farr, Research Associate, Yale Law School. The writer also wishes to point out, as bearing on his bias in favor of the decision in the School Segre- gation Cases, that he worked peripherally on the briefs in those cases as a member of tho NAACP's National Legal Committee, and has been of counsel for plaintiffs in the Girard College Case, note 11 infra. -

Hugo Black's Vision of the Lawyer, the First Amendment, and the Duty of the Judiciary: the Bar Applicant Cases in a National Security State

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 20 (2011-2012) Issue 3 Article 3 March 2012 Hugo Black's Vision of the Lawyer, the First Amendment, and the Duty of the Judiciary: The Bar Applicant Cases in a National Security State Joshua E. Kastenberg Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Repository Citation Joshua E. Kastenberg, Hugo Black's Vision of the Lawyer, the First Amendment, and the Duty of the Judiciary: The Bar Applicant Cases in a National Security State, 20 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 691 (2012), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol20/iss3/3 Copyright c 2012 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj HUGO BLACK’S VISION OF THE LAWYER, THE FIRST AMENDMENT, AND THE DUTY OF THE JUDICIARY: THE BAR APPLICANT CASES IN A NATIONAL SECURITY STATE Joshua E. Kastenberg* INTRODUCTION .................................................691 I. THE COURT AND ATTORNEY GOVERNANCE ........................698 II. THE COURT, THE COLD WAR, AND CHALLENGES TO THE HISTORIC MODEL OF ATTORNEY GOVERNANCE ...................................712 A. Anticommunist Legislation .................................715 B. Federal Law on Economic Regulation and the Criminalization of Speech ...............................................718 C. Dennis v. United States....................................721 D. The Court Under Attack ...................................727 E. United States v. Sacher....................................728 F. In re Isserman ...........................................738 G. Other Prosecutions: Black’s Fears of a Double Standard .........742 1. Rosenberg Trial ......................................743 2. Cammer v. United States ...............................744 H. State Loyalty Programs Affecting Public Employment ............745 III. -

Constitutional Right Or Legislative Grace? the Status of Conscientious Objection Exemptions

Florida State University Law Review Volume 19 Issue 1 Article 7 Summer 1991 Constitutional Right or Legislative Grace? The Status of Conscientious Objection Exemptions Spencer E. Davis, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Spencer E. Davis, Jr., Constitutional Right or Legislative Grace? The Status of Conscientious Objection Exemptions, 19 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 191 (1991) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol19/iss1/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT OR LEGISLATIVE GRACE? THE STATUS OF CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTION EXEMPTIONS SPENCER E. DAVIS, JR. C ONSCRIPTION is not currently used to fill the ranks of the United States military,' but the mechanism necessary to imple- ment the draft stands ready to be set in motion. Males between the ages of eighteen and twenty-six are required to register with Selective Service. 2 The Code of FederalRegulations contains provisions for the induction of registered males to be used in the event that the draft is reactivated.' These regulations and the portions of the United States Code authorizing them4 contain express provisions concerning the ex- emption of conscientious objectors from compulsory military service.' 1. The draft ended on July 1, 1973. Act of Sept. 28, 1971, Pub. L. No. 92-129, § 101(a)(35), 85 Stat. -

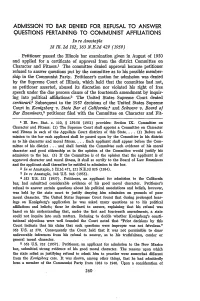

ADMISSION to BAR DENIED for REFUSAL to ANSWER QUESTIONS PERTAINING to COMMUNIST AFFILIATIONS in Re Anastaplo 18 II

ADMISSION TO BAR DENIED FOR REFUSAL TO ANSWER QUESTIONS PERTAINING TO COMMUNIST AFFILIATIONS In re Anastaplo 18 II. 2d 182, 163 N.E.2d 429 (1959) Petitioner passed the Illinois bar examination given in August of 1950 and applied for a certificate of approval from the district Committee on Character and Fitness.' The committee denied approval because petitioner refused to answer questions put by the committee as to his possible member- ship in the Communist Party. Petitioner's motion for admission was denied by the Supreme Court of Illinois, which held that the committee had not, as petitioner asserted, abused its discretion nor violated his right of free speech under the due process clause of the fourteenth amendment by inquir- ing into political affiliations.2 The United States Supreme Court denied certiorari.3 Subsequent to the 1957 decisions of the United States Supreme Court in Konigsberg v. State Bar of California,4 and Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners,5 petitioner filed with the Committee on Character and Fit- 1 Ill.Rev. Stat. c. 110, § 259.58 (1951) provides: Section IX. Committee on Character and Fitness: (1) The Supreme Court shall appoint a Committee on Character and Fitness in each of the Appellate Court districts of this State.... (2) Before ad- mission to the bar each applicant shall be passed upon by the Committee in his district as to his character and moral fitness .... Each applicant shall appear before the Com- mittee of his district ...and shall furnish the Committee such evidence of his moral character and good citizenship as in the opinion of the Committee would justify his admission to the bar.