Suffragists Picketing the White House, 1917

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

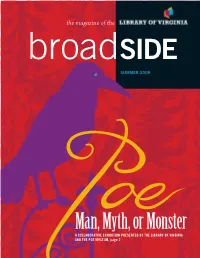

Man, Myth, Or Monster

the magazine of the broadSIDE SUMMER 2009 Man, Myth, or Monster A COLLABORATIVE EXHIBITION PRESENTED BY THE LIBRARY OF VIRGINIA AND THE POE MUSEUM, page 2 broadSIDE THE INSIDE STORY the magazine of the LIBRARY OF VIRGINIA Nurture Your Spirit at a Library SUMMER 2009 Take time this summer to relax, recharge, and dream l i b r a r i a n o f v i r g i n i a Sandra G. Treadway hatever happened to the “lazy, hazy, crazy days of l i b r a r y b o a r d c h a i r Wsummer” that Nat King Cole celebrated in song John S. DiYorio when I was growing up? As a child I looked forward to summer with great anticipation because I knew that the e d i t o r i a l b o a r d rhythm of life—for me and everyone else in the world Janice M. Hathcock around me—slowed down. I could count on having plenty Ann E. Henderson of time to do what I wanted, at whatever pace I chose. Gregg D. Kimball It was a heady, exciting feeling—to have days and days Mary Beth McIntire Suzy Szasz Palmer stretched out before me with few obligations or organized activities. I was free to relax, recharge, enjoy, explore, and e d i t o r dream, because that was what summer was all about. Ann E. Henderson My feeling that summer was a special time c o p y e d i t o r continued well into adulthood, then gradually diminished Emily J. -

American Women's Suffrage Movement

RESOURCE GUIDE: AMERICAN WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT On July 18, 1848, women and men gathered to launch the women’s suffrage movement in the United States at the Seneca Falls Convention, held in Seneca Falls, New York. This struggle would last seven decades, with women gaining the right to vote in 1920. The women’s suffrage movement, also called woman suffrage, gave women the opportunity to express themselves to the general public, which had rarely been done prior. Not all women supported women’s suffrage. Women who opposed suffrage believed that it would take them away from their families and homes, and that women would be tainted by “dirty” politics. In 1909, the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia formed to campaign for women to gain the right to vote in the Commonwealth of Virginia. Founding members included Lila Meade Valentine, who would be elected as the organization’s leader; artists Adele Clarke and Nora Houston; writers Ellen Glasgow and Mary Johnston; and physician Kate Waller Barrett. These women traveled throughout Virginia handing out literature, giving speeches, hosting suffrage teas, and lobbying men and General Assembly members to grant women the right to vote. Following the formation of the Equal Suffrage League, its members decided to become a part of the national suffrage movement by joining the National American Woman Suffrage Association. The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia and National American Woman Suffrage Association members supported the fight for women’s suffrage on a state level, while other suffrage organizations supported a constitutional amendment. While the National American Woman Suffrage Association and its affiliated groups were making progress in their individual states, some suffragists became frustrated by the slow pace of the movement. -

How Women Won the Vote

Equality Day is August 26 March is Women's History Month National Women's History Project How Women Won the Vote 1920 Celebrating the Centennial of Women's Suffrage 2020 Volume Two A Call to Action Now is the Time to Plan for 2020 Honor the Successful Drive for Votes for Women in Your State ENS OF THOUSANDS of organizations and individuals are finalizing plans for extensive celebrations for 2020 in honor Tof the 100 th anniversary U.S. women winning the right to vote. Throughout the country, students, activists, civic groups, artists, government agen- cies, individuals and countless others are prepar- ing to recognize women's great political victory as never before. Their efforts include museum shows, publica- tions, theater experiences, films, songs, dramatic readings, videos, books, exhibitions, fairs, pa- rades, re-enactments, musicals and much more. The National Women's History Project is one of the leaders in celebrating America's women's suffrage history and we are encouraging every- one to recognize the remarkable, historic success of suffragists one hundred years ago. Here we pay tribute to these women and to the great cause to which they were dedicated. These women overcame unbelievable odds to win their own civil rights, with the key support of male voters and lawmakers. This is a celebration for both women and men. Join us wherever you are. There will be many special exhibits and obser- vances in Washington D.C. and throughout the WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE nation, some starting in 2019. Keep your eyes open; new things are starting up every day. -

Equal Suffrage League of Virginia Records: Selected Timeline

Equal Suffrage League of Virginia Records: Selected Timeline ESL BRIEF TIMELINE Nov. 1909 Equal Suffrage League of Virginia (ESL) organized 1910 ESL members began circulating a petition to present to the 1912 session of the General Assembly (“to propose and submit to the qualified voters for ratification an amendment to the Constitution of Virginia, whereby women shall have the right of suffrage….”) Dec. 1910 ESL state convention held in Richmond Dec. 1911 ESL state convention held in Richmond Jan.–Feb. 1912 ESL members spoke to General Assembly committees in favor of woman suffrage, but House of Delegates defeats a proposed amendment by a vote of 85 to 12 Feb. 1912 Virginia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (VAOWS) organized Oct. 1912 ESL state convention held in Norfolk 1912–1915 ESL officers, especially president Lila Meade Valentine, vice president Elizabeth D. Lewis, and novelist Mary Johnston, speak in localities around the state and help organize local leagues Mar. 1913 ESL members and more than 100 Virginians participate in the national suffrage parade in Washington, D.C. Oct. 1913 ESL state convention held in Lynchburg Feb. 1914 ESL members speak to General Assembly committees, but House of Delegates rejects a suffrage resolution by vote of 74 to 13 May 1914 ESL Suffrage Day demonstration held at Capitol Square Oct.–Dec. 1914 ESL publishes Virginia Suffrage News Nov. 1914 ESL state convention held in Roanoke May 1915 ESL Suffrage Day celebration at Capitol Square June 1915 Virginia branch of Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage organized (later becomes the National Woman’s Party) Dec. 1915 ESL state convention held in Richmond; also participates in meeting of the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference Jan.–Feb. -

Bibliography of Petersburg Research Resources

Toward an Online Listing of Research Resources for Petersburg This listing was developed by Dulaney Ward about 2008 in connection with the Atlantic World Initiative at Virginia State University. As with all bibliographies, it remains a "work in progress." It is being made available for use by those who recognize and wish to learn more about Petersburg's rich history. _____. Acts of the General Assembly Relative to Jurisdictions and Powers of the Town of Petersburg To Which Are Added the Ordinances, Bye-Laws, and Regulations of the Corporation. Petersburg: Edward Pescud, 1824. _____. Act to Incorporate the Petersburg Rail Road Company. Petersburg, 1830. _____. A Guide to the Fortifications and Battlefields around Petersburg. Petersburg: Daily Index Job Print, for Jarratt’s Hotel, 1866. [CW; Postbellum.] _____. Annual Register and Virginian Repository for the Year 1800. Petersburg, 1801. _____. Charter and By-Laws of the Petersburg Benevolent Mechanic Association. Revised October, 1900. Petersburg: Fenn & Owen, 1900. _____. Charter, Constitution snd By-Laws. Petersburg Benevolent Mechanic Association. Petersburg, 1858, 1877. _____. City of Petersburg, Virginia: The Book of Its Chamber of Commerce. Petersburg: George W. Englehardt, 1894. Rare. PPL. [Photographs and etchings of local businessmen and their buildings, with brief company history.] _____. Civil War Documents, Granville County, N.C. 2 vols. Oxford, North Carolina: Granville County His- torical Society, n.d. [CW.] _____. Contributions to a History of the Richmond Howitzer Battalion.Baltimore: Butternut and Blue, 2000. [CW.] _____. Cottom’s New Virginia and North Carolina Almanack, for the Year of Our Lord 1820, Calculated by Joseph Case, of Orange County, Virginia.; Adapted to the Latitude and Meridian of Richmond. -

None) Building Names Be Landmarks/Locations Combined Name from a White & Black Leader in Civil Rights Movement

# Times Suggested Name Rationale Mascot Suggested 18 (None) building names be landmarks/locations combined name from a white & black leader in civil rights movement do not name school after a person name all schools w/numbers because someone will now be offended by any name name indicating locale of the school name school by location, numbers, but not people name schools after geographical area in which they reside pick a generic name that will bring peace & unity, not a historical name refrain from naming after a person, but choose a name that does not cause undo distraction but empowers all to focus on education start naming schools after things other than people this is a waste of money to taxpayers and unnecessary - schools have been integrated - this issue was solved years ago 1 A Number 1 Adele Goodman Clarke Va. suffragist and artist 2 Alice Jackson Stuart Richmonder and advocate for education Attended VUU 1 Alicia Rasin late Richmond advocate for peace 1626 Alysia C. Burton Byrd alumni who lost her life on 9/11 Petition submitted – 100 signatures her name is the right choice & will serve students well into the future name suggested by Alysia's husband to honor friend & classmate and to give her family a positive association with her name instead of tragedy Petition submitted – 1,506 signatures 1 American Flag 1 Ann Spencer African-American Harlem Renaissance Poet in 20th century 1 Anything Goes 1 Arrohattoc Indian tribe who predates any English settlement 2 Arthur Ashe 1 Bach after an achiever in science, math or art 13 Barack H. -

After Committee Meeting #6) Significant Contribution to Alexandria - Living

WEST END ELEMENTARY SCHOOL NAMES RECOMMENDED TO SCHOOL BOARD (after committee meeting #6) Significant Contribution to Alexandria - Living Significant Contribution to Alexandria - Deceased Virginia Historical Figures - Living ˃ Katherine Johnson Virginia Historical Figures - Deceased National Historical Figures - Living ˃ Barack & Michelle Obama ˃ Sonia Sotomayor National Historical Figures - Deceased Places/Entities/Historical Events Related to School Location Cross-Category Names ˃ Day-Ochoa (Ferdinand T. Day & Dr. Ellen Ochoa) Names NO LONGER Under Consideration (after committee meeting #6) 1 Abigail Adams 2 Abraham Lincoln 3 Abyssinia 4 Alexander Hamilton 5 Alexandria 6 Alonzo Bumbry 7 A. Melvin Miller (or Melvin/Eula Miller) 8 Anne Spencer 9 Arlene Moore 10 Barack Obama-Guzman 11 Barbara Rose Johns 12 Beacon 13 Beauregard 2/8/18 ALEXANDRIA CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS 1 14 Bill Clinton 15 Bill Euille (William D. Euille) 16 Blue Diamonds Paradise 17 Booker T. Washington 18 Bynum 19 Cardinal 20 Catherine Winkler Herman 21 Chief Powhatan 22 Clifford 23 Crawley 24 Crystal River 25 Dave Grohl *COMMITTEE NOTE: FUTURE CONSIDERATION FOR MUSIC ROOM?* 26 Day-Miller 27 Day-Sotomayor (or Sotomayor-Day) 28 Do not name after a person 29 Dorothy Vaughn 30 Douglas E. Wilder 31 Dr. Seuss 32 Duke Ellington 33 Dwayne Johnson 34 Edmonson 35 Edwin B. Henderson 36 Eleanor Roosevelt 37 Elizabeth Guzman 38 Ella Fitzgerald 39 Ellen Ochoa 40 Elmer E. Ellsworth 41 Ferdinand T. Day 42 Fitzhugh Lee 43 Francis 44 Freedom 45 Funn-Day (Carlton Funn & Ferdinand T. Day) 46 Future Legends of Alexandria 47 George Lewis Seaton 48 Gerry Bertier 49 Gloria E Anzaldúa 50 H.J. -

1/11/18 Alexandria City Public Schools 1 Recommended

RECOMMENDED NAMES FOR NEW WEST END ELEMENTARY SCHOOL STILL UNDER CONSIDERATION (after committee meeting #4) Significant Contribution to Alexandria - Living 1 Arlene Moore Significant Contribution to Alexandria - Deceased 2 A. Melvin Miller 3 Edmonson 4 Ferdinand T. Day 5 Funn-Day (Carlton Funn & Ferdinand T. Day) 6 Harriet Ann Jacobs 7 Margaret Brent 8 Mary E. Randolph 9 Rocky Versace or Humbert Roque Versace 10 Sarah A. Gray Virginia Historical Figures - Living 11 Douglas E. Wilder 12 Katherine Johnson 13 Johnson-Vaughn-Jackson STEM School or the Johnson-Vaughn-Jackson Elementary School Virginia Historical Figures - Deceased 14 Barbara Rose Johns 15 Mary Jackson 16 Mildred and Richard Loving National & International Historical Figures - Living 17 Barack/Michelle Obama 18 Ellen Ochoa 19 Ruth Bader Ginsburg 20 Sonia Sotomayor 21 Sylvia Mendez 1/11/18 ALEXANDRIA CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS 1 Names NO LONGER Under Consideration (after committee meeting #4) 1 Abigail Adams 2 Abraham Lincoln 3 Abyssinia 4 Alexander Hamilton 5 Alexandria 6 Alonzo Bumbry 7 Anne Spencer 8 Barack Obama-Guzman 9 Beacon 10 Beauregard 11 Bill Clinton 12 Bill Euille (William D. Euille) 13 Blue Diamonds Paradise 14 Booker T. Washington 15 Bynum 16 Cardinal 17 Catherine Winkler Herman 18 Chief Powhatan 19 Clifford 20 Crawley 21 Crystal River 22 Dave Grohl *COMMITTEE NOTE: FUTURE CONSIDERATION FOR MUSIC ROOM?* 23 Do not name after a person 24 Dr. Seuss 25 Duke Ellington 26 Dwayne Johnson 27 Edwin B. Henderson 28 Eleanor Roosevelt 29 Elizabeth Guzman 30 Ella Fitzgerald 31 Elmer E. Ellsworth 32 Fitzhugh Lee 33 Francis 34 Freedom 35 Future Legends of Alexandria 36 George Lewis Seaton 37 Gerry Bertier 38 Gloria E Anzaldúa 39 H.J. -

Alexandria Celebrates Women 100 Years of Women’S Right to Vote

Alexandria Celebrates Women 100 Years of Women’s Right to Vote April 2020 Newsletter Editor: Gayle Converse Media Relations, [email protected] 404.989.0534 “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” - 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution Welcome to the April 2020 newsletter of Alexandria Celebrates Women -- 100 Years of Women’s Right to Vote. A Special Message 1 Alexandria Celebrates Women (ACW) sends its wishes for health and happiness to you and your family during the COVID 19 outbreak. All women are concerned about health and wellbeing, isolation and economic stability at this time. Many of us are able to work from home during this crisis. Others have experienced the temporary or permanent loss of their jobs. Our hearts go out to all. We extend our sincere thanks to those brave professionals who are risking their lives to safeguard our health, feed our populations, protect us from harm, ensure the delivery of the U.S. Mail and essential items, and other vital services. The COVID19 crisis reminds us of another time when Alexandria’s women were looked to as a source of social and economic fortitude during one of the world’s deadliest pandemics. More than 100 years ago – before the 19th Amendment was ratified – women nursed U.S. soldiers and others fallen victim to the 1918 Influenza outbreak and stepped in to fill military and civilian jobs traditionally held by men who were now sick or away fighting in World War I. -

NPS Form 10 900 OMB No. 1024 0018

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012} United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use In nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions. architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative Items on continuation sheets If needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Crenshaw House other names/site number Younger House; Clay House; DHR # 127-0228-0029 2. Location street & number 919 West Franklin Street 0 not for publication city or town -----'---'--------------------Richmond ------- D vicinity state Vir inia code VA county --------N/A code __76_ 0_ zip code _2_3_22_0__ _ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated author~y under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _X_ nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _L meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local --..::_ ..L - ~~ Signature of certifying offici~ Date y?~./d t__f/~c:? nue State or Federal agenc y/bureau or Tribal Govemment In my opinion , the property _ meels _does not meet the National Register crileria. -

Virginia State History -- Reconstruction to 1900

Virginia State History -- Reconstruction to 1900 Freedmen Schools Richmond Destroyed 1865 Virginia History Series #14 © 2010 Civil War Destruction in Virginia (Grant’s Army Shown Destroying a RR Line during his Overland Campaign) The Civil War took its toll on many bridges across the Potomac River and C&O Canal. At 4am on June 14, 1861, Stonewall Jackson's Confederate Army blew up Harpers Ferry bridge. The railroad and turnpike bridge was rebuilt nine times during the Civil War, although it was never rebuilt as a covered wooden bridge. The Union Army destroyed the bridge in July 1863. Besides the 1861 demolition, the Confederate Army destroyed the bridge in September 1862 and again in July 1864. The piers of the old covered bridge and its subsequent bridges can still be seen in the Potomac River. Ruins of RR Bridge at Harper’s Ferry In the spring of 1862, Gen. Johnston withdrew his Confederate army south to defend Richmond. According to the book Fairfax Virginia: A City Traveling Through Time, the withdrawal of thousands of soldiers revealed the magnitude of destruction to Centreville, Virginia. “In less than one year, the devastation wreaked by soldiers living in primitive camps and relying mostly on their immediate surroundings for survival left the region a stark and hollow image of its former self.” A Union soldier described Centreville and surrounding areas in a letter home to Pennsylvania in April.…”The Rebels have spent immense labor in fortifying that position. It is surrounded on all sides by forts and Earth works of great size and strength, between the Junction and Bull Run nothing but one Fortification after another is to be seen. -

Select Bibliography of Virginia Women's History

GENERAL AND REFERENCE James, Edward T., Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, eds. Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary. 3 vols. 1971. Kneebone, John T., et al., eds. Dictionary of Virginia Biography. 1998– . Lebsock, Suzanne. “A Share of Honour”: Virginia Women, 1600–1945. 1984; 2d ed., Virginia Women, 1600–1945: "A Share of Honour." 1987. Scott, Anne Firor. Natural Allies: Women's Associations in American History. 1991. Sicherman, Barbara, and Carol Hurd Green, eds. Notable American Women: The Modern Period. 1980. Strasser, Susan. Never Done: A History of American Housework. 1982. Tarter, Brent. "When 'Kind and Thrifty Husbands' Are Not Enough: Some Thoughts on the Legal Status of Women in Virginia." Magazine of Virginia Genealogy 33 (1995): 79–101. Treadway, Sandra Gioia. "New Directions in Virginia Women's History." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 100 (1992): 5–28. Wallenstein, Peter. Tell The Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage, and Law: An American History. 2002. 1 NATIVE AMERICANS Axtell, James, ed. The Indian Peoples of Eastern America: A Documentary History of the Sexes. 1981. Barbour, Philip L. Pocahontas and Her World. 1970. Green, Rayna. "The Pocahontas Perplex: The Image of Indian Women in American Culture." Massachusetts Review 16 (1975): 698–714. Lurie, Nancy Oestreich. "Indian Cultural Adjustment to European Civilization." In Seventeenth-Century America: Essays in Colonial History, edited by James Morton Smith. 1959. Rountree, Helen C. The Powhatan Indians of Virginia: Their Traditional Culture. 1989. Rountree, Helen C. Pocahontas's People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia through Four Centuries. 1990. Smits, David D. "'Abominable Mixture': Toward the Repudiation of Anglo-Indian Intermarriage in Seventeenth-Century Virginia." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 95 (1987): 157–192.