Reviews Marvels & Tales Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Popular British Ballads : Ancient and Modern

11 3 A! LA ' ! I I VICTORIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SHELF NUMBER V STUDIA IN / SOURCE: The bequest of the late Sir Joseph Flavelle, 1939. Popular British Ballads BRioky Johnson rcuvsrKAceo BY CVBICt COOKe LONDON w J- M. DENT 5" CO. Aldine House 69 Great Eastern Street E.G. PHILADELPHIA w J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY MDCCCXCIV Dedication Life is all sunshine, dear, If you are here : Loss cannot daunt me, sweet, If we may meet. As you have smiled on all my hours of play, Now take the tribute of my working-day. Aug. 3, 1894. eooccoc PAGE LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS xxvii THE PREFACE /. Melismata : Musical/ Phansies, Fitting the Court, Cittie, and Countrey Humours. London, 1 6 1 i . THE THREE RAVENS [MelisMtata, No. 20.] This ballad has retained its hold on the country people for many centuries, and is still known in some parts. I have received a version from a gentleman in Lincolnshire, which his father (born Dec. 1793) had heard as a boy from an old labouring man, " who could not read and had learnt it from his " fore-elders." Here the " fallow doe has become " a lady full of woe." See also The Tiua Corbies. II. Wit Restored. 1658. LITTLE MUSGRAVE AND LADY BARNARD . \Wit Restored, reprint Facetix, I. 293.] Percy notices that this ballad was quoted in many old plays viz., Beaumont and Fletcher's Knight of the xi xii -^ Popular British Ballads v. The a Act IV. Burning Pestle, 3 ; Varietie, Comedy, (1649); anc^ Sir William Davenant's The Wits, Act in. Prof. Child also suggests that some stanzas in Beaumont and Fletcher's Bonduca (v. -

Download PDF Booklet

LIZZIE HIGGINS UP AND AWA’ WI’ THE LAVEROCK 1 Up and Awa Wi’ the Laverock 2 Lord Lovat 3 Soo Sewin’ Silk 4 Lady Mary Ann 5 MacDonald of Glencoe 6 The Forester 7 Tammy Toddles 8 Aul’ Roguie Gray 9 The Twa Brothers 10 The Cruel Mother 11 The Lassie Gathering Nuts First published by Topic 1975 Recorded and produced by Tony Engle, Aberdeen, January 1975 Notes by Peter Hall Sleeve design by Tony Engle Photographs by Peter Hall and Popperfoto Topic would like to thank Peter Hall for his help in making this record. This is the second solo record featuring the singing of Lizzie The Singer Higgins, one of our finest traditional singers, now at the height Good traditional singers depend to a considerable extent upon of her powers. The north-east of Scotland has been known for their background to equip them with the necessary artistic 200 years as a region rich in tradition, and recent collecting experience and skill, accumulated by preceding generations. has shown this still to be the case. Lizzie features on this It is not surprising then to find in Lizzie Higgins a superb record some of the big ballads for which the area is famed, exponent of Scots folk song, for she has all the advantages of such as The Twa Brothers, The Cruel Mother and The Forester. being born in the right region, the right community and, Like her famous mother, the late Jeannie Robertson, she has most important of all, the right family. The singing of her the grandeur to give these pieces their full majestic impact. -

The Gilchrist Collection

The Gilchrist Collection This collection consists of correspondence, songs, tunes, and miscellaneous materials that belonged to Anne Geddes Gilchrist, a long-time member of the Folk-Song Society and then the English Folk Dance and Song Society. Gilchrist served the societies in many ways—as vice-president, as annotator and tune expert extraordinaire for the journals, and as ‘Aunt Anne,’ a mentor to many people in the societies and in the scholarly folklore community. The items range in date from 1894 to 1951. When the collection was given to the EFDSS after Gilchrist’s death, Margaret Dean-Smith was the librarian at the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. She began sorting and categorizing the papers, labeling the envelopes with the contents. However, whether that project was interrupted or just never finished, the notes on many of the envelopes do not match what is in the envelopes. Also, although Dean-Smith did seem to be trying to put together physically those items that were on the same topic, often the same song or same subject appears in several places in the collection. The index must be used in order to find all relevant materials on a topic, song, or person. AGG = Anne Geddes Gilchrist LEB = Lucy E. Broadwood MDS = Margaret Dean-Smith FH = Frank Howes FK = Frank Kidson CSJ = Cecil J. Sharp PSS = Pat Shuldham-Shaw RVW = Ralph Vaughan Williams Box 1 1 [The contents of the boxes originally numbered Gilchrist 1 and Gilchrist 8 are now in the box numbered Gilchrist 1.] All the tunes in the tune books are in AGG’s handwriting unless otherwise noted. -

Oral Tradition 29.1

_____________________________________________________________ Volume 29 March 2014 Number 1 _____________________________________________________________ Founding Editor John Miles Foley () Editor Managing Editor John Zemke Justin Arft Editorial Assistants Rebecca Benson Elise Broaddus Katy Chenoweth Christopher Dobbs Ruth Knezevich IT Manager Associate Editor for ISSOT Mark Jarvis Darcy Holtgrave Please direct inquiries to: Center for Studies in Oral Tradition University of Missouri 21 Parker Hall Columbia, MO 65211 USA +573.882.9720 (ph) +573.884.0291 (fax) [email protected] E-ISSN: 1542-4308 Each contribution copyright © 2014 by its author. All rights reserved. The editors and the publisher assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion by the authors. Oral Tradition (http://journal.oraltradition.org) seeks to provide a comparative and interdisciplinary focus for studies in oral tradition and related fields by publishing research and scholarship on the creation, transmission, and interpretation of all forms of oral traditional expression. In addition to essays treating certifiably oral traditions, OT presents investigations of the relationships between oral and written traditions, as well as brief accounts of important fieldwork, and occasional transcriptions and translations of oral texts. In addition, issues will include the annual Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lecture on Oral Tradition. Submissions should follow the list-of-reference format (http:// journal.oraltradition.org/files/misc/oral_tradition_formatting_guide.pdf) and may be sent via e-mail ([email protected]); all quotations of primary materials must be made in the original language(s) with following English translations. If appropriate, please describe any supporting materials that could be used to illustrate the article, such as photographs, audio recordings, or video recordings. -

The Songs of Scotland

«& • - ' m¥Hi m THE GLEN COLLECTION OF SCOTTISH MUSIC Presented by Lady DOROTHEA RUGGLES-BRISE to the National Library of Scotland, in memory of her brother, Major Lord George Stewart Murray, Black Watch, killed in action in France in 1914. 28th January 1927. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/songsofscotland02grah A THE SONGS OF SCOTLAND ADAPTED TO THEIR APPROPRIATE MELODIES ARRANGED WITH PIANOFORTE ACCOMPANIMENTS BY G. F. GRAHAM, T. M. MTJDIE, J. T. SURENNE,, H. E. DIBDIN, FINLAY DUN, &c. 3Hu8ttateb n»it^» historical, 55iogra:pfjical, anb Sritical Notices BY GEORGE FARQUHAR GRAHAM, AUTHOR OF THE ARTICLE "MUSIC" IN THE SEVENTH EDITION OP THE ENCYCLOPEDIA EE.ITANNICA, ETC. ETO. VOL III. WOOD AND CO., 12, WATERLOO PLACE, EDINBURGH; J. MUIR CO., BUCHANAN STREET, GLASGOW WOOD AND 42, ; OLIVER & BOYD, EDINBURGH; CRAMER, BEALE, & CHAPPELL, REGENT STREET; CHAPPELL, NEW BOND STREET ; ADDISON & HODSON, REGENT STREET ; J. ALFRED NOVELLO, DEAN STREET; AND SLMPKIN, MARSHALL, & CO., LONDON. MDCCCXLIX. EDINBURGH : PRINTED BY T. CONSTABLE, PRINTER TO IIER MAJESTT. INDEX TO THE FIRST LINES OP THE SONGS IN THE THIRD VOLUME. FAGB - PAGE Accuse me not, inconstant fair, 48 On Cessnock banks, .... 146 Again rejoicing Nature sees, 62 } On Ettrick banks, ae simmer nicht, (App. 168, 169,) 52 And we're a' noddin', nid, nid, noddin', 38 ) O once my thyme was young, (note,) . 85 why leaves thou thy Nelly to ? 56 A piper came to our town, (note and App.) 7,167 \ O Sandy, mourn A rosebud by my early walk, 86 O speed, Lord Nithsdale, .. -

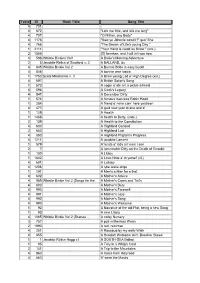

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4 701 - 4 672 "Lo'e me little, and lo'e me lang" 4 707 "O Mither, ony Body" 4 1176 "Saw ye Johnnie comin'?" quo' She 4 766 "The Dream of Life's young Day " 1 2111 "Your Hand is cauld as Snaw " (xxx.) 2 1555 [O] hearken, and I will tell you how 4 596 Whistle Binkies Vol1 A Bailie's Morning Adventure 2 5 Jacobite Relics of Scotland v. 2 A BALLAND, &c 4 845 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 A Bonnie Bride is easy buskit 4 846 A bonnie wee lassie 1 1753 Scots Minstrelsie v. 3 A Braw young Lad o' High Degree (xxi.) 4 597 A British Sailor's Song 1 573 A cogie o' ale an' a pickle aitmeal 4 598 A Cook's Legacy 4 847 A December Dirty 1 574 A famous man was Robin Hood 1 284 A friend o' mine cam' here yestreen 4 477 A guid new year to ane and a' 1 129 A Health 1 1468 A health to Betty, (note,) 2 139 A Health to the Constitution 4 600 A Highland Garland 2 653 A Highland Lad 4 850 A Highland Pilgram's Progress 4 1211 A jacobite Lament 1 579 A' kinds o' lads an' men I see 2 7 A lamentable Ditty on the Death of Geordie 1 130 A Litany 1 1842 A Love-Note a' to yersel' (xi.) 4 601 A Lullaby 4 1206 A lyke wake dirge 1 291 A Man's a Man for a that 4 602 A Mother's Advice 4 989 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Songs for the A Mother's Cares and Toil's 4 603 Nursery) A Mother's Duty 4 990 A Mother's Farewell 4 991 A Mother's Joys 4 992 A Mother's Song 4 993 A Mother's Welcome 1 92 A Narrative of the old Plot; being a new Song 1 93 A new Litany 4 1065 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Scenes … A noisy Nursery 3 757 Nursery) A puir mitherless Wean 2 1990 A red, red rose 4 251 A Rosebud by my early Walk 4 855 A Scottish Welcome to H. -

A Book of Old Ballads

ECLECTIC ENGLISH CLASSICS A BOOK OF O LD BALLAD S EDITED BY O R A /l O RTO N M A C {t , . NORWOOD HIGH SCHOOL NOR O W OD, OHIO AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY NEW YO RK PRE FACE £ 9 T h rs a reed o a eac e of English are generally g that the—l gic l t im e t o use ballads is in the early adolescent period in the l n of first years of the high school , or perhaps the last year the { — grammar grades yet the st andard ballad anthologies are t oo f m l o full and too unsifted or such use . Fro these larger col ecti ns not only the best known and the most typical examples have been chosen but also the best version of each . As the ballads were unwritten in the beginning and were m for m o n orally trans itted any generati ns , the spelli g of the fif f early manuscripts is the spelling of the transcriber. The t eent h and sixteenth century ballad lovers knew the sounds Of wo nl o m the rds o y, and the written f r s in which they have been preserved are merely makeshift devices for visualizing m n t he m o . th se sounds The ore u obtrusive akeshift, the less is o m the attenti n distracted fro the sound and the sense, and the nearer are we to receiving the story as the early listeners m r in received it . For this reason fa iliar wo ds the ballads in this book are printed in the familiar spelling of to- day except where rhyme or rhythm demanded the retention of an older m of a for . -

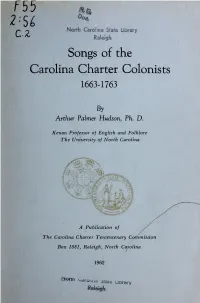

Songs of the Carolina Charter Colonists, 1663-1763 Digitized by the Internet Archive

F55 j North Carolina State Library Raleigh Songs of the Carolina Charter Colonists 16634763 By Arthur Palmer Hudson, Ph. D. Kenan Professor of English and Folklore The University of North Carolina <-*roma orafe Library Relei§h Songs of the Carolina Charter Colonists, 1663-1763 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/songsofcarolinac1962huds Songs of the Carolina Charter Colonists 16634763 By Arthur Palmer Hudson, Ph. D. Kenan Professor of English and Folklore The University of North Carolina A Publication of The Carolina Charter Tercentenary Commission Box 1881, Raleigh, North Carolina 1962 ttortft Carolina Sfare Library THE CAROLINA CHARTER TERCENTENARY COMMISSION Hon. Francis E. Winslow, Chairman Henry Belk Mrs. Kauno A. Lehto Mrs. Doris Betts James G. W. MacLamroc Dr. Chalmers G. Davidson Mrs. Harry McMullan Mrs. Everett L. Durham Dr. Paul Murray William C. Fields Dan M. Paul William Carrington Gretter, Jr. Dr. Robert H. Spiro, Jr. Grayson Harding David Stick Mrs. James M. Harper, Jr. J. P. Strother Mrs. Ernest L. Ives Mrs. J. O. Tally, Jr. Dr. Henry W. Jordan Rt. Rev. Thomas H. Wright Ex-Officio Dr. Charles F. Carroll, Robert L. Stallings, Superintendent of Director, Department of Public Instruction Conservation and Developm Dr. Christopher Crittenden, Director, Department of Archives and History Secretary The Carolina Charter Tercentenary Commission was established by the North Carolina General Assembly to "make plans and develop a program for celebration of the tercentenary of the granting of the ." Carolina Charter of 1663 . As part of this program the Com- mission arranged for the publication of a number of historical pamphlets for use in stimulating interest in the study of North Carolina history during the period 1663-1763. -

Francis James Child and William Macmath Working Together for Ballads

THE CAUSE Francis James Child and William Macmath Working Together for Ballads Mary Ellen Brown• • , Editor Contents Acknowledgements The Cause The Letters Index Acknowledgments The letters between Francis James Child and William Macmath reproduced here belong to the permanent collections of the Houghton Library, Harvard University and the Hornel Library, Broughton House, Kirkcudbright, a National Trust for Scotland property. I gratefully acknowledge the help and hospitality given me by the staffs of both institutions and their willingness to allow me to make these materials more widely available. My visits to both facilities in search of data, transcribing hundreds of letters to bring home and analyze, was initially provided by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial and Andrew W. Mellon foundations and subsequently—for checking my transcriptions and gathering additional material--by the Office of the Provost for Research at Indiana University Bloomington. This serial support has made my work possible. Quite unexpectedly, two colleagues/friends met me the last time I was in Kirkcudbright (2014) and spent time helping me correct several difficult letters and sharing their own perspectives on these and other materials—John MacQueen and the late Ronnie Clark. Robert E. Lewis helped me transcribe more accurately Child’s reference and quotation from Chaucer; that help reminded me that many of the letters would benefit from copious explanatory notes in the future. Much earlier I benefitted from conversations with Sigrid Rieuwerts and throughout the research process with Emily Lyle. Both of their published and anticipated research touches on related publications as they have sought to explore and make known the rich past of Scots and the study of ballads. -

The Persistence of Fairy Culture in Scotland, 1572-1703 and 1811-1927

“What are ye, little mannie?”: The Persistence of Fairy Culture in Scotland, 1572-1703 and 1811-1927 Alison Marie Hight Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Danna Agmon (Co-Chair) David Cline (Co-Chair) Matthew Gabriele May 5, 2014 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: Scotland, fairy, national identity, cultural heritage, witchcraft, escapism, class culture “What are ye, little mannie?”: The Persistence of Fairy Culture in Scotland, 1572-1703 and 1811-1927 Alison Marie Hight ABSTRACT This thesis is a chronologically comparative study of fairy culture and belief in early modern and Victorian Scotland. Using fairy culture as a case study, I examine the adaptability of folk culture by exploring whether beliefs and legends surrounding fairies in the early modern era continued into the nineteenth and early twentieth as a single culture system, or whether the Victorian fairy revival was a distinct cultural phenomenon. Based on contextual, physical, and behavioral comparisons, this thesis argues the former; while select aspects of fairy culture developed and adapted to serve the needs and values of Victorian society, its resurgence and popularization was largely predicated on the notion that it was a remnant of the past, therefore directly linking the nineteenth century interpretation to the early modern. In each era, fairy culture serves as a window into the major tensions complicating Scottish identity formation. In the early modern era, these largely centered around witchcraft, theology, and the Reformation, while notions of cultural heritage, national mythology, and escapist fantasy dominated Victorian fairy discourse. -

Minstrelsy, Music, and the Dance in the English and Scottish Popular Ballads

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism English, Department of January 1921 Minstrelsy, Music, and the Dance in the English and Scottish Popular Ballads Lowry Charles Wimberly University of Nebraska Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishunsllc Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Wimberly, Lowry Charles, "Minstrelsy, Music, and the Dance in the English and Scottish Popular Ballads" (1921). University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism. 10. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishunsllc/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA. STUDIES IN LANGUAGE, LITERATURE, AND CRITICISM NUMBER 4. MINSTRELSY, MUSIC, AND THE DANCE IN THE ENGLISH AND SCOTTISH POPULAR BALLADS BY LOWRY CHARLES WIMBERLY, A. M. EDITORIAL COMMITTEE LOUISE POUND, Ph. D., Department of English H. B. ALEXANDER, Ph. D., Department of Philosophy H. H. VAUGHAN, Ph. D., Department of Romance Languages LINCOLN 1 9 2 1 CONTENTS I INTRODUCTION The pastimes of the ballad in relation to the theme of the ballad. -The ballad narrative rather than descriptive.-Rapid action in the ballad.-Pastimes not ordinarily an essential part of the action.-Minstrelsy, music, and the dance in King Estmere and The Bonny Lass 01 Anglesey.-Pastimes usually portrayed in casual descriptive touches.-Purpose of the present study. Importance of recreational interests in the ballad.-The place of music in the present study. -

The Medieval British Ballads Their Age, Origins and Authenticity

1 The Medieval British Ballads Their Age, Origins and Authenticity By Garry Victor Hill 2 3 The Medieval British Ballads: Their Age, Origins and Authenticity By Garry Victor Hill Frisky Press Armidale Australia 2015 4 Contents Dedication: Page 5 Copyright: Page 6 Acknowledgements: Page 7 Author’s Note: Page 8 Introduction: Page 9 Part One: Problems with Sources and Methods Page 9 Part Two: The Origins of the Ballads Page 22 Part Three: Depictions of the world of Medieval Music Page 33 Part Four: The Ballad and the End of Medieval Society Page 40 Part Five: The Songs Page 56 Part Six The Robin Hood Ballads Page 233 Afterword: Page 306 About the Author Page 307 5 Dedication To the balladeers who inspired: Joan Baez Rusty MacKenzie Harry Belafonte Jacki MacShee Theo Bikel Ewan McColl Eric Bogle Loreena McKennitt Arthur Bower Jane Modrick Isla Cameron Margret Monks Alex Campbell Derek Moule Ian Campbell David Nolan Judy Collins Pentangle Sandy Denny Maddy Prior Cara Dillon Jean Redpath Donovan John Renborn Judith Durham Jean Ritchie Marianne Faithful Kate Rusby Fairport Convention The Seekers Athol De Fugard Pete Seeger Arlo Guthrie Gary Shearston Woody Guthrie Steeleye Span Emmylou Harris Bill Staines Tim Hart Martha Tilston Faye Held Ian and Sylvia Tyson Mike Heron Robin Williamson Alex Hood and Peter, Paul and Mary Burl Ives Roger Illott and Penny Davies 6 Copyright © The text written by the author may be quoted from for purposes of study or review if proper acknowledgement is made. For the whole book storage in electronic systems or bound printed out copies for library research is also allowed.