Survival and Change in the Paintings of Winston S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Leeds Arts Club and the New Age: Art and Ideas in a Time of War by Tom Steele Thank You Very Much Nigel, That's a Very Generous Introduction

TRANSCRIPT Into the Vortex: The Leeds Arts Club and the New Age: Art and Ideas in a Time of War by Tom Steele Thank you very much Nigel, that's a very generous introduction. Thank you for inviting me back to the Leeds Art Gallery where I spent so many happy hours. As Nigel said, the book was actually published in 1990, but it was a process of about 5 or 6 year work, in fact it's turned into a PHD. I've not done a lot of other work on it since, I have to say some very very good work has been done on Tom Perry and other peoples in the meantime, and it's grievously in danger of being the new edition, which I might or might not get around to, but maybe somebody else will. Anyway, what I'm going to do is to read a text. I'm not very good at talking extensively, and it should take about 40 minutes, 45 minutes. This should leave us some time for a discussion afterwards, I hope. Right, I wish I'd thought about the title and raw text before I offered the loan up to the gallery, because it makes more sense, and you'll see why as we go along. I want to take the liberty of extending the idea of war to cover the entire decade 1910-1920, one of the most rebellious and innovative periods in the history of British art. By contrast, in cultural terms, we now live in a comparatively quiet period. -

The Atlanta Preservation Center's

THE ATLANTA PRESERVATION CENTER’S Phoenix2017 Flies A CELEBRATION OF ATLANTA’S HISTORIC SITES FREE CITY-WIDE EVENTS PRESERVEATLANTA.COM Welcome to Phoenix Flies ust as the Grant Mansion, the home of the Atlanta Preservation Center, was being constructed in the mid-1850s, the idea of historic preservation in America was being formulated. It was the invention of women, specifically, the ladies who came J together to preserve George Washington’s Mount Vernon. The motives behind their efforts were rich and complicated and they sought nothing less than to exemplify American character and to illustrate a national identity. In the ensuing decades examples of historic preservation emerged along with the expanding roles for women in American life: The Ladies Hermitage Association in Nashville, Stratford in Virginia, the D.A.R., and the Colonial Dames all promoted preservation as a mission and as vehicles for teaching contributive citizenship. The 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition held in Piedmont Park here in Atlanta featured not only the first Pavilion in an international fair to be designed by a woman architect, but also a Colonial Kitchen and exhibits of historic artifacts as well as the promotion of education and the arts. Women were leaders in the nurture of the arts to enrich American culture. Here in Atlanta they were a force in the establishment of the Opera, Ballet, and Visual arts. Early efforts to preserve old Atlanta, such as the Leyden Columns and the Wren’s Nest were the initiatives of women. The Atlanta Preservation Center, founded in 1979, was championed by the Junior League and headed by Eileen Rhea Brown. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Winston Churchill, the Morning Post and the End of the Imperial Romance Journal Item How to cite: Griffiths, Andrew (2013). Winston Churchill, the Morning Post and the End of the Imperial Romance. Victorian Periodicals Review, 46(2) pp. 163–183. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2013 The Research Society for Victorian Periodicals https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1353/vpr.2013.0016 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Winston Churchill, the Morning Post and the End of the Imperial Romance. Brief Biography: Andrew Griffiths studied at the University of Exeter and teaches at Plymouth University and the Open University. His research addresses the relationship between New Imperialism, New Journalism and fiction in the late nineteenth century. He is currently working on a project which focuses on the role of the special correspondent at the heart of this relationship. Abstract: Winston Churchill’s Morning Post correspondence from Kitchener’s 1898 Sudan expedition documents a shift in the practice and reportage of imperialism. Sensational New Journalism and aggressive New Imperialism had been locked in a mutually-supportive relationship. Special correspondents, including Churchill, emphasised the romance of empire. -

The Female Art of War: to What Extent Did the Female Artists of the First World War Con- Tribute to a Change in the Position of Women in Society

University of Bristol Department of History of Art Best undergraduate dissertations of 2015 Grace Devlin The Female Art of War: To what extent did the female artists of the First World War con- tribute to a change in the position of women in society The Department of History of Art at the University of Bristol is commit- ted to the advancement of historical knowledge and understanding, and to research of the highest order. We believe that our undergraduates are part of that endeavour. For several years, the Department has published the best of the annual dis- sertations produced by the final year undergraduates in recognition of the excellent research work being undertaken by our students. This was one of the best of this year’s final year undergraduate disserta- tions. Please note: this dissertation is published in the state it was submitted for examination. Thus the author has not been able to correct errors and/or departures from departmental guidelines for the presentation of dissertations (e.g. in the formatting of its footnotes and bibliography). © The author, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the prior permission in writing of the author, or as expressly permitted by law. All citations of this work must be properly acknowledged. Candidate Number 53468 THE FEMALE ART OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR 1914-1918 To what extent did the female artists of the First World War contribute to a change in the position of women in society? Dissertation submitted for the Degree of B.A. -

Interview with Lady Soames “FATHER ALWAYS CAME FIRST, SECOND and THIRD”

! An Interview with Lady Soames “FATHER ALWAYS CAME FIRST, SECOND AND THIRD” Finest Hour 116, Autumn 2002 As Churchill’s daughter, Mary Soames had the run of 10 Downing Street and helped arrange dinner with Stalin. She talks to Graham Turner about eighty rich and varied years. Graham Turner is a journalist whom we knew years ago when he covered the motor industry and wrote a penetrating, oft-quoted book, The Leyland Papers. He has since moved to weightier subjects for the Daily Telegraph, by whose kind permission this article is reprinted. “I don’t think I was necessarily intended,” said Mary Soames, Winston and Clementine Churchill’s youngest daughter, “but I suppose I was the child of consolation. My parents were shattered when their third daughter, Marigold—who was only two and a half years old—died in 1921. It’s clear from letters my father wrote to my mother that, when I arrived the following year, he was delighted that the nursery had started again.” ! Mary Soames The way in which Marigold died was to have a decisive influence on Lady Soames’s own life. “Mummy had left her in the charge of a French nursery governess, Mademoiselle Rose, while she went to stay with the Duke and Duchess of Westminster at their home in Cheshire. Marigold, who was known as “Duckadilly” in the family, developed a very sore throat but, even when she became really ill, the governess still waited a day or two before sending for my mother. By that time, there was nothing even a specialist could do for her. -

First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill Free Ebook

FREEFIRST LADY: THE LIFE AND WARS OF CLEMENTINE CHURCHILL EBOOK Sonia Purnell | 400 pages | 14 May 2015 | Aurum Press Ltd | 9781781313060 | English | London, United Kingdom Biography of Clementine Churchill, Britain's First Lady First Lady is a bold biography of a bold woman; at last Purnell has put Clementine Churchill at the centre of her own extraordinary story, rather than in the shadow of her husband's.' 'From the influence she wielded to the secrets she kept, a new book looks at the extraordinary role of Winston Churchill's wife Clementine who proved that behind. First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill, review: 'fascinating account of an under appreciated woman' Geoffrey Lyons reviews Sonia Purnell’s enthralling new biography of one of Britain’s most misunderstood figures. Keeping silent was, Purnell argues, Clementines most decisive and courageous action of the war. Anne Sebba is the author of American Jennie, The Remarkable Life of Lady Randolph Churchill (WW Norton ) and is currently writing Les Parisiennes: how Women lived, loved and died in Paris from for publication in First Lady: The Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill, review: 'fascinating account of an under appreciated woman' Geoffrey Lyons reviews Sonia Purnell’s enthralling new biography of one of Britain’s most misunderstood figures. Royal Oak lecturer Sonia Purnell’s new book, “First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill,” is out to rave reviews. Examining Clementine’s role in some of the critical events of the 20th century, Purnell retells a history that has largely marginalized Sir Winston’s wife. -

Copyright Statement

COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. i ii REX WHISTLER (1905 – 1944): PATRONAGE AND ARTISTIC IDENTITY by NIKKI FRATER A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Humanities & Performing Arts Faculty of Arts and Humanities September 2014 iii Nikki Frater REX WHISTLER (1905-1944): PATRONAGE AND ARTISTIC IDENTITY Abstract This thesis explores the life and work of Rex Whistler, from his first commissions whilst at the Slade up until the time he enlisted for active service in World War Two. His death in that conflict meant that this was a career that lasted barely twenty years; however it comprised a large range of creative endeavours. Although all these facets of Whistler’s career are touched upon, the main focus is on his work in murals and the fields of advertising and commercial design. The thesis goes beyond the remit of a purely biographical stance and places Whistler’s career in context by looking at the contemporary art world in which he worked, and the private, commercial and public commissions he secured. In doing so, it aims to provide a more comprehensive account of Whistler’s achievement than has been afforded in any of the existing literature or biographies. This deeper examination of the artist’s practice has been made possible by considerable amounts of new factual information derived from the Whistler Archive and other archival sources. -

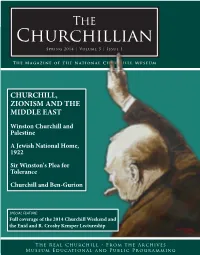

Spring 2014 | Volume 5 | Issue 1

The Churchillian Spring 2014 | Volume 5 | Issue 1 The Magazine of the National Churchill Museum CHURCHILL, ZIONISM AND THE MIDDLE EAST Winston Churchill and Palestine A Jewish National Home, 1922 Sir Winston's Plea for Tolerance Churchill and Ben-Gurion SPECIAL FEATURE: Full coverage of the 2014 Churchill Weekend and the Enid and R. Crosby Kemper Lectureship The Real Churchill • From the Archives Museum Educational and Public Programming Board of Governors of the Association of Churchill Fellows FROM THE Jean-Paul Montupet MESSAGE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Chairman & Senior Fellow St. Louis, Missouri A.V. L. Brokaw, III Warm greetings from the campus of St. Louis, Missouri Westminster College. As I write, we are Robert L. DeFer still recovering from a wonderful Churchill th Weekend. Tis weekend, marking the 68 Earle H. Harbison, Jr. St. Louis, Missouri anniversary of Churchill’s visit here and his William C. Ives Sinews of Peace address, was a special one for Chapel Hill, North Carolina several reasons. Firstly, because of the threat R. Crosby Kemper, III of bad weather which, while unpleasant, Kansas City, Missouri never realized the forecast’s dismal potential Barbara D. Lewington and because of the presence of members of St. Louis, Missouri the Churchill family, Randolph, Catherine St. Louis, Missouri and Jennie Churchill for a frst ever visit. William R. Piper Tis, in tandem with a wonderful Enid St. Louis, Missouri PHOTO BY DAK DILLON and R. Crosby Kemper Lecture delivered by Paul Reid, defed the weather and entertained a bumper crowd of St. Louis, Missouri Churchillians at both dinner, in the Museum, and at a special ‘ask the experts’ brunch. -

Abstract the Power of Place in the Fiction of E.M. Forster

ABSTRACT THE POWER OF PLACE IN THE FICTION OF E.M. FORSTER Ashley Diedrich, M.A. Department of English Northern Illinois University, 2014 Brian May, Director By taking a close look at each of E.M. Forster's novels, readers can learn that he, like other authors, appears to be telling the same story over and over again. It is the story of the human desire to connect, even if it means having to adjust that desire to social reality. In each of his novels, he creates characters who struggle through a series of events and complications to reconcile their unique identities with the norms of society, the purpose being to attain significant relationship. But in addition to exploring this theme of authentic connection in the face of countervailing pressures, Forster is also exploring the idea of place and the difference it makes. In all of the novels, place is significant in bringing about different opportunities for connection: Italy in Where Angels Fear to Tread and A Room with a View; pastoral England in The Longest Journey and Howards End; the "greenwood" in Maurice; and India, his most exotic location, in A Passage to India. In this thesis I emphasize the essential element of place in Forster’s characters' quests to develop their hearts and connect. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DE KALB, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2014 THE POWER OF PLACE IN THE FICTION OF E.M. FORSTER BY ASHLEY DIEDRICH ©2014 Ashley Diedrich A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Thesis Director: Brian May TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1. -

Post-War & Contemporary

post-wAr & contemporAry Art Sale Wednesday, november 21, 2018 · 4 Pm · toronto i ii Post-wAr & contemPorAry Art Auction Wednesday, November 21, 2018 4 PM Post-War & Contemporary Art 7 PM Canadian, Impressionist & Modern Art Design Exchange The Historic Trading Floor (2nd floor) 234 Bay Street, Toronto Located within TD Centre Previews Heffel Gallery, Calgary 888 4th Avenue SW, Unit 609 Friday, October 19 through Saturday, October 20, 11 am to 6 pm Heffel Gallery, Vancouver 2247 Granville Street Saturday, October 27 through Tuesday, October 30, 11 am to 6 pm Galerie Heffel, Montreal 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest Thursday, November 8 through Saturday, November 10, 11 am to 6 pm Design Exchange, Toronto The Exhibition Hall (3rd floor), 234 Bay Street Located within TD Centre Saturday, November 17 through Tuesday, November 20, 10 am to 6 pm Wednesday, November 21, 10 am to noon Heffel Gallery Limited Heffel.com Departments Additionally herein referred to as “Heffel” consignments or “Auction House” [email protected] APPrAisAls CONTACT [email protected] Toll Free 1-888-818-6505 [email protected], www.heffel.com Absentee And telePhone bidding [email protected] toronto 13 Hazelton Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5R 2E1 shiPPing Telephone 416-961-6505, Fax 416-961-4245 [email protected] ottAwA subscriPtions 451 Daly Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K1N 6H6 [email protected] Telephone 613-230-6505, Fax 613-230-8884 montreAl CatAlogue subscriPtions 1840 rue Sherbrooke Ouest, Montreal, Quebec H3H 1E4 Heffel Gallery Limited regularly publishes a variety of materials Telephone 514-939-6505, Fax 514-939-1100 beneficial to the art collector. -

The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870

The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Dzanic, Dzavid. 2016. The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33840734 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870 A dissertation presented by Dzavid Dzanic to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2016 © 2016 - Dzavid Dzanic All rights reserved. Advisor: David Armitage Author: Dzavid Dzanic The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870 Abstract This dissertation examines the religious, diplomatic, legal, and intellectual history of French imperialism in Italy, Egypt, and Algeria between the 1789 French Revolution and the beginning of the French Third Republic in 1870. In examining the wider logic of French imperial expansion around the Mediterranean, this dissertation bridges the Revolutionary, Napoleonic, Restoration (1815-30), July Monarchy (1830-48), Second Republic (1848-52), and Second Empire (1852-70) periods. Moreover, this study represents the first comprehensive study of interactions between imperial officers and local actors around the Mediterranean. -

Sir John Lavery's the Dentist

Sir John Lavery’s The Dentist IN BRIEF • Sir John Lavery’s portrait of The Dentist (Conrad Ackner and his Patient) is an GENERAL unusual departure for a painter renowned (Conrad Ackner and his Patient) for his portraits of the contemporary celebrities. K. McConkey1 • It shows its subject in action. His patient, Hazel Lavery, one of the great beauties of the day, is partially obscured. • Lavery’s depiction of dentists’ equipment gives us an almost unprecedented view of a surgery of the 1920s. The rise of the dental profession coinciding with the invention and rapid spread of photography means that there are very few paintings of dentists in action. The present article describes Sir John Lavery’s unusual depiction of The Dentist (Conrad Ackner and his Patient) in which the conventions of contemporary society portraiture are set aside. The resulting canvas has much to tell us about the up-to-date equipment used in a surgery of the late twenties by a successful practitioner who pioneered the use of X‑rays. In 1929, Sir John Lavery exhibited one of in 1926, one commentator dubbed the com- His career blossomed after he moved his most striking portraits – The Dentist missions Lavery received in New York, Long to London and purchased 5 Cromwell (Conrad Ackner and his Patient) (Fig. 1). Island and Boston as portraits of ‘million- Famed for his pictures of society host- aires surrounded by their millions’.2 esses, political leaders and members of the The artist was 70 when this new genre Royal Family, Lavery had recently devel- emerged.