ECKART LEMBERG. Born 1928. TRANSCRIPT of OH 1747V A-C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engineered Endurance Apparel

FALL/WINTER 2013 ENGINEERED ENDURANCE APPAREL www.cw-x.com CW-X® CONDITIONING WEAR® SUPPORT TECHNOLOGIES Scientists at the Wacoal Human Science Research Center in Biomechanical studies at the WHSRC using body-mapping sensors and high-speed video analysis have shown: Kyoto, Japan, have extensively studied kinesiology, the science of • Lower torso/leg stability and balance during running is human movement. They have come to understand the mechanics increased in CW-X® Support Web™ tights over standard stretch running tights. of joints and muscles in minute detail. This exhaustive study of • Knee impact during the foot-strike phase is reduced body movement has culminated in CW-X® Conditioning Wear® in CW-X® Support Web™ tights versus standard stretch running tights. and over 15 US patents. • Using electromyography testing technology to measure electrical pulse activity of the muscles, CW-X® Support Web™ tights show a reduced rate of fatigue during and after exercise than regular stretch tights or shorts. CW-X® US Patents Stabilyx Tights PAT. 5263923 Insulator Stabilyx PAT. 5263923 The CW-X® Conditioning Cycle PAT. 6186970 Tights PAT. 6186970 8 3/4 Length PAT. 5263923 3/4 Length Insulator PAT. 5263923 1 1 CW-X® Conditioning Wear® products Stabilyx Tights PAT. 6186970 Stabilyx Tights PAT. 6186970 are designed to optimize the 3 phases of CW-X® Patented Support Web™ technology provides Stabilyx Ventilator PAT. 404889 the conditioning cycle. Shorts Targeted Support and Xcelerated Recovery. Ventilator Tights PAT. 5263923 PAT. 6186970 Expert Tights PAT. 5367708 3/4 Length PAT. 5263923 1 ARGETED UPPORT T S PAT. 6186970 Ventilator Tights PAT. -

RANKING ISF 2013 International Skyrunning Federation

RANKING ISF 2013 International Skyrunning Federation SKY DISTANCE WOMEN OVERVIEW International Skyrunning Federation 216 ATHLETES SELECTED 29 NATIONS 21 RACES IN FIVE CONTINENTS RACES International Skyrunning Federation TRAIL DU VENTOUX (FRA) MONT-BLANC MARATHON (FRA) MARATHON DU MONT CALM (FRA) 3 PEAKS RACE (GBR) OLYMPUS MARATHON (GRE) PIKES PEAK MARATHON (USA) ELBRUS SKYMARATHON (RUS) KILIAN’S CLASSIK (FRA) MATTERHORN ULTRAKS 46K (SUI) ZEGAMA-AIZKORRI (ESP) MARATONA DEL CIELO (ITA) BEN NEVIS RACE (GBR) ZIRIA CROSS COUNTRY (GRE) DOLOMITES SKYRACE (ITA) WMRA WORLD CHAMPS (POL) INTERNATIONAL SKYRACE (ITA-SUI) GIIR DI MONT (ITA) SKYRUNNING EXTREME (ITA) MARATON ALPINO MADRILENO (ESP) SIERRE-ZINAL (SUI) MT KINABALU CLIMBATHON (MAS) PARAMETERS International Skyrunning Federation For each athlete in each event, the ISF alogorithm is based on the following: RACE POSITION TIME RELATIVE TO WINNER NUMBER OF ELITE ATHLETES AHEAD NUMBER OF ELITE ATHLETES BEHIND BEST THREE-SEASON PERFORMANCE TOP 50 ATHLETES International Skyrunning Federation 1 EMELIE FORSBERG SWE 315,000 11 DEBORA CARDONE ITA 194,116 2 STEVIE KREMER USA 288,664 12 ANNA LUPTON GBR 192,559 3 NURIA PICAS ALBETS ESP 287,982 13 RAGNA DEBATS NED 190,822 4 SILVIA SERAFINI ITA 261,145 14 DOMINIKA WISNIEWSKA POL 190,529 5 EMANUELA BRIZIO ITA 240,775 15 ANTONELLA CONFORTOLA ITA 187,886 6 MAITE MAYORA ELIZONDO ESP 234,240 16 LAIA ANDREU TRIAS ESP 181,923 7 NURIA DOMINGUEZ AZPELETA ESP 232,455 17 TESSA HILL GBR 178,468 8 UXUE FRAILE AZPEITIA ESP 213,823 18 LEIRE AGUIRREZABALA ESP 175,118 9 -

Pag. Kilian Nell'estate 2010 Su Quelle Che Sono Diventate

KILIAN NELL’ESTATE 2010 SU QUELLE CHE SONO DIVENTATE LE SUE MONTAGNE DI CASA. SULLO SFONDO IL GHIACCIO DELLA MER DE GLACE, CHAMONIX (FOTO P. TOURNAIRE) NELLA PAGINA A FRONTE KILIAN CON IN MANO LE SUE FEDELI COMPAGNE DA CORSA (FOTO ARCH. SALOMON) 280 / PAG. 48 48-58 ALP 280 Kilian.indd 48 06/04/12 11.18 crescere verso l’interno intervista di GIULIO CARESIO «Prima ancora che potessimo Uno dei più grandi atleti camminare io e mia sorella avevamo già percorso il nostro primo chilometro in sci» racconta Kilian, nato da genitori sulla piazza rivela che hanno le montagne nel sangue, in un paesino dei Pirenei catalani. «Lassù la sua grande sensibilità. lo sport era l’unico divertimento che avessimo a disposizione». Sono le emozioni A 5 anni ha già salito le due cime più alte dei Pirenei (Aneto e Posets) la sua benzina. entrambe oltre i 3000 m; a 10 ha attraversato gli stessi Pirenei e archiviato varie vette sopra i 4000 m. È a quest’età che gareggiando su una bici Visti i suoi incredibili risultati assaggia il gusto della competizione. nelle competizioni di questi ultimi anni Intorno ai 13 anni inizia a frequentare il Centro Tecnico della Catalunya per lo sci chi non lo conosce potrebbe pensare alpinismo, dove dice «ho iniziato ad che sia un uomo macchina, allenarmi davvero, tutti i giorni, grazie a votato all’allenamento sportivo e poco Maité Hernández che mi ha insegnato a lottare e Jordi Canals che mi ha sempre propenso a parlare di altri argomenti. sostenuto con la sua passione per lo Niente di più sbagliato. -

2005 Final Challenger Race, Tokyo, Apr 29

For Immediate Release – March 17, 2005 – Happy St. Patrick’s Day Contact: Nancy Hobbs, PO Box 9454 Colorado Springs, CO 80932 (719) 573-4133 Fax (719) 573-4408 E-mail: [email protected] US Mountain Runners to Compete on the Trails in Japan Six athletes will represent the United States in the inaugural 100-kilometer Japan mountain race, the “Challenger’s Race 2005,” which is to be held in the suburban mountains of Tokyo on April 29 2005. According to organizer and Japanese businessman Todd Itezono, “The event will be used as a tool to pinpoint and emphasize the wonderfulness of the natural and physical world and will serve to stress the importance of how human beings need to live symbiotically with nature, to preserve them by running through a trail, under trees, and next to plants and flowers, so to avoid any further man-made natural disasters. By inviting runners from other countries, we want to stress that such an action needs combined effort from everybody on earth, because nature does not belong to only one country but to all humanity.” The race will be run on the Okutama Mountain range outside Tokyo and will offer courses at 10km, 50km, and 100km as well as relay competition. More than 1500 runners are expected and an estimate of 10,000 spectators. US team members will compete in the 10km event, the 50km, and the 100km. The course ranges in elevations from 200 meters to more than 2000 meters. “On behalf of USA Track and Field and the World Mountain Running Association, I am delighted to be a part of this mission and look forward to competing on the trails in Japan. -

Pikes Peak Marathon: Aug

Pikes Peak Marathon: Aug. 19, 2007 Notes: 1. Acclimatization—Arriving on Wednesday for the race on Sunday worked out well, particularly since the house we rented was at 9200’. Germaine arrived on Friday and also did well. A minimum of two nights at altitude before the race is essential and our plans this year were pretty close to perfect. 2. Acclimatization Hikes—I did nothing on Wednesday, an easy 6-miler on Thursday, the top 2 miles of Pikes Peak on Friday and a very light 3-miler at Pancake Rocks on Saturday. I would have preferred to have gone all the way down to the A-Frame (3 miles) on Friday but we were pinched for time. Also, Germaine had to do this fresh off the plane, no easy task! The toll for the auto road to the summit was $10/person. 3. Clothing—I wore pure running gear and was glad I did. My biggest pre-race equipment choice was between running shoes and trail hikers. Running shoes proved the best choice. Unlike my experience at the Grand Canyon where the running shoes were completely destroyed, on Pikes Peak they were in perfect shape at the end. There is no reason to wear heavy, protective shoes on the Barr Trail. Also, depending on the weather, a short sleeved running shirt is fine. Even if it’s a bit chilly in the morning it is best to start with short sleeves. You warm up quickly once the race begins. Germaine started out with long sleeves but quickly stripped down. -

Pikes Peak Release Anita

For Immediate Release – August 24, 2004 CONTACT: Nancy Hobbs, (719) 573-4405 Fax (719) 573-4408 E-mail: [email protected] Teva U.S. Mountain Running Team Member Wins Fourth Pikes Peak Manitou Springs, Colorado ---- Three-time Teva US Mountain Running Team member Anita Ortiz set an age group record en route to her fourth victory at the Pikes Peak Ascent on Saturday, August 21. The race starts at an elevation of 6,295 feet (1,918 meters)with a summit elevation of 14,110 feet (4,299 meters) making the net elevation gain 7,815 feet (2,381 meters). The total distance is 13.32 miles with an average grade of 11%. The 40-year-old mother of four led from the start to post a 2:44:58 nearly eight minutes faster than her winning time from 2003 and close to her best time of 2:44:33 from 2002. “The footing was good most of the way, but there were some areas with ankle-deep water and some icy spots near the top. My legs felt great, my breathing was a bit off, probably related to the time off from my injury (in May Ortiz suffered a stress fracture in her hip),” said Ortiz. Second place finisher Leanne Whitesides, 34, Grand Junction, CO finished in 2:59:09 while Nancy L Citriglia, 30, Winter Park, CO placed third in 3:09:36. Scott Elliott won the men’s division in 2:23:31 earning the 40-year-old Boulder resident his eight victory. While most athletes who finish Pikes Peak reflect on their present race before thinking about the future, Ortiz was already thinking about 2005 when she plans to try the Pikes Peak Marathon. -

Volume 9 • Issue 3 • November 2010 Board of Directors Members Watch for the 2011 Renewal Form in the Next Newsletter

Discover Publications, 6797 N. High St., #213, Worthington, OH 43085 PRESORTED STANDARD U.S. POSTAGE Stats, New Members, Demographics . 3 Running and Cycling in Scenic WV . 12 PAID Finishers & Milestones . 4 Are You on the A Team or B Team. 13 DISCOVER PUBLICATIONS Member Profiles . 5 Grizzly Marathon & Shorts . 14 Member Profiles & Brookings. 6 Tupelo & ADT. 15 Destination Marathon & Shorts. 7 Germantown & Shorts. 16 Hooked on Marathoning & Shorts. 8 Running in Rio. 17 Omaha Reunion. 9 Doubles & Deals for Members . 18 Smowmaggedon Marathon. 10 Member Events . 19 Winthrop & Run with Horses. 11 Reunions & Advertising Info . 20 Volume 9 • Issue 3 • November 2010 DP #11101 NEWSLETTER 50 States Marathon Club • PO Box 15638, Houston, TX 77220 • www.50statesmarathonclub.com • Volume 9 • Issue 3 • November 2010 Board of Directors Members Watch for the 2011 renewal form in the next newsletter. • President • Tom Adair [email protected] What is the best finisher medal/award you have received? • Vice President/Reunions • (answers from the 2010 profile) Charles Sayles • Paris Marathon, Little Rock, First Light, Chicago—Randy Maugle,PA [email protected] • Taos, NM—Harry Hoffman, Jr.,FL • Secretary • • Barcelona Spain, March 1998—Jeannette Roostai,CA Susan Sinclair • Big Sur, Comrades and Antarctica—Tom Adair,GA [email protected] • Little Rock (huge) and Disney Goofy—Rick Crawshaw,NY • Treasurer • • A bottle of wine at the Medoc Marathon in France—Jodi Lee Alper,NJ Steve Boone • Marathon to Marathon—John Holland,PA [email protected] • Atlanta 1991 because it was the first—Ken Ott,CO • Membership • • My first marathon on 11/2/97 in New York City—Donald Arthur,NY Paula Boone • No favorites. -

Disciplina Geo Fuente Informativa Mes Sem Día

MES SEM DÍA DISCIPLINA GEO EVENTO ORGANIZADOR FUENTE INFORMATIVA RESULTADO Enero 1 SAB 02 DOM 03 2 SAB 09 Carrera Asfalto NAME Walt Disney World® Half Marathon. Orlando, Florida. E.U.A. Cygna http://www.rundisney.com/disneyworld-marathon/ DOM 10 Carrera Asfalto NAME Walt Disney World® Marathon. Orlando, Florida. E.U.A. Cygna http://www.rundisney.com/disneyworld-marathon/ Carrera Trail OCE Bogong to Hotham Trail Run. New Zealand https://sites.google.com/site/bogong2hotham/ Triatlón y Aventura SAME HERBALIFE IRONMAN 70.3 PUCON. Pucon, Chile IRONMAN 70.3 Events http://www.ironman.com/triathlon/events/americas/ironman- 3 SAB 16 Carrera Asfalto AFR Egyptian Marathon. Egipto http://www.egyptianmarathon.com/EgyptianMarathon/70.3/pucon.aspx#axzz3wJBCl0ZI DOM 17 4 SAB 23 DOM 24 Carrera Trail NAC Trail Manzanillo 12K Carrera de Montaña. Isla de Margarita. Nueva Esparta TRAIL VENEZUELA http://trailvenezuela.com/ Carrera Asfalto NAME Miami Marathon and Half Marathon. Florida, EUA. Miami Marathon http://www.themiamimarathon.com/ Carrera Trail NAME Arrowhead 135. Winter Ultra Marathon. Minnesota. E.U.A. http://www.arrowheadultra.com Triatlón y Aventura AFR Standard Bank IRONMAN 70.3 South Africa Buffalo City, East London IRONMAN 70.3 Events http://www.ironman.com/triathlon/events/emea/ironman- 5 SAB 30 Triatlón y Aventura ASI IRONMAN 70.3 DUBAI. Dubai, United Arab Emirates IRONMAN 70.3 Events http://www.ironman.com/triathlon/events/emea/ironman-70.3/south-africa.aspx#axzz3wJBCl0ZI DOM 31 Carrera Asfalto NAC Media Maratón San Sebastian. San Cristobal, Tachira FEVEATLETISMO http://www.feveatletismo.com/70.3/dubai.aspx#axzz3wJBCl0ZI Carrera Trail NAC Media Maratón de Montaña 21K La Fragua, San Antonio de Los Altos. -

The Bulletin of the Dolphin Swimming & Boating Club

WINTER 2018 DOLPHIN LOG THE BULLETIN OF THE DOLPHIN SWIMMING & BOATING CLUB • SAN FRANCISCO • ESTABLISHED 1877 Once ’Round the Cove News From the Archives ‘Were you ever a member of the Communist Party?’ Dolphin Log e are already in our fi fth year! Th ere made to appear on work days for horseplay - Keith Howell, Editor Whave been 46 scheduled 4-hour work breaking into lockers.” Joe Illick, Editor sessions from the start in 2014 through Dangers of card playing: In April, May Sunny McKee, Graphic Designer the end of 2017. A total of 42 members and June 1952, the Board voted to restrict Andrew Cassidy, Swim Stats have worked over 848 volunteer hours, card games to the galley and ban them Story Rafter, Proofreader not including time at home to input data. entirely from the Staib Room. In June, Club Archivist Th anks to all of you! members voted to rescind the ban (except Morgan Kulla In February, we received ten boxes of for minors), but with conditions. Th ere must very old club records plus research by late be “monitors,” players should “police their Published By Club historian, Walt Schneebeli. A real own games,” and those “who use profanity Th e Dolphin Swimming treasure trove! will be brought before Board of Governors.” & Boating Club Currently, we are digitizing and Saving Aquatic Park: In 1960 the Board 502 Jeff erson Street indexing old Board minutes, including the discussed a private group’s plan to rebuild San Francisco, CA 94109 handwritten minutes 1949-1960. Reading Aquatic Park into a “small boat harbor with www.dolphinclub.org them is full of surprises! For example: a series of land locked heated swimming Board of Governors Party bargains: Tickets for the April 1947 pools.” Th e Dolphin Club joined forces Diane Walton, Andrew Wynn, Installation Dinner Dance at the Sir Francis with the South End to object. -

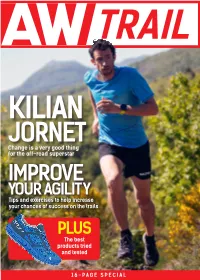

Trails PLUS the Best Products Tried and Tested

T R A I L KILIAN JORNET Change is a very good thing for the off-road superstar IMPROVE YOUR AGILIT Y Tips and exercises to help increase your chances of success on the trails PLUS The best products tried and tested 16-PAGE SPECIAL TRAIL KILIAN JORNET @ATHLETICSWEEKLY TRAIL CONTENTS 2 Kilan Jornet on setting targets and weighing up risks 6 Running the volcano at the VVX Experience in France 8 Tame the trails with exercises which will improve your agility 12 Kit yourself out for an off-road adventure with the best products Kilian Jornet: has won all three of the races he Changing set as his main targets DAM GEMILI goes into this meeting for the IAAF World as an individual, as well as in the – and to run the same time as him, weekend’s world trials in Championshipsman (see p42-45). 4x100m,” he says. “I went the closest I’m happy,” he said. great form after pushing Not bad for an athlete only that anyone from Britain has gone On doubling up at the world trials, former worldTRAIL champion AND MOUNTAINconsidered good RUNNING enough to be part SUPERSTAR to winning an KILIANOlympic 200m JORNET TALKShe added: “It’ll be a long weekend AYohan Blake to the wire at the of the relay squad when the last medal three years ago. Just three and then I’ll really start to sharpen TO EUAN CRUMLEY ABOUT BECOMING A FATHER AND ADOPTING Diamond League in Birmingham Aon DIFFERENTwave of Lottery fundingAPPROACH decisions TO thousandthsTHE SPORT of a second HE LOVEScame up before Doha. -

Zima 2018 Runandtravel.Pl Magazyn on Line

ZIMA 2018 RUNANDTRAVEL.PL MAGAZYN ON LINE ŚWIĘTA, POGODA DLA ŚWIĘTA BIEGACZY JAK TO SIĘ ROBI? Transgrancanaria Jak spędzają Bieganie w trudnych Boże Narodzenie warunkach - opowieści BIEGOWA MAPA ŚWIATA biegacze na całym biegaczy. świecie? Przegląd kurtek Biegi etapowe 2019 Zainspiruj się! wsze Najcieka biegi e trailow W POLSCE, EUROPIE, NA ŚWIECIE... ZNAJDZIESZ NA... JESIEŃ, ZIMA, WIOSNA, LATO... Właśnie rytm pór roku będzie wyznaczał zarówno termin publikacji kolejnych wydań naszego Magazynu on-line, jak i poruszane w nim tematy wiodące. Swoje miejsce w Magazynie znajdą jednak nie tylko tematy związane z konkretną porą roku, ale również takie, które będą "magazynowym" rozszerzeniem tego, co już od kilku lat robimy w ramach portalu www.runandtravel.pl. Zapraszamy do lektury wydania zimowego! Zdjęcie na okładce: Zimowy Janosik 2018 / Monika Dratwa 14 24 6 38 28 6 Festiwal biegów, filmów i spotkań 28 Na biegaczu kurtka... Gore "Biegun Zimna" / Suwalszczyzna Wywiad z Jakubem Dyrlico 8 ISPO Munich 2019 12 Czytaj i biegaj! 32 Kurtki wodoodporne/ Przegląd 14 ŚWIĘTA, ŚWIĘTA! 36 Membrany Jak biegacze spędzają Boże Narodzenie. 38 Czy puch grzeje? Wywiad z Wojciechem Kłapcią 23 POGODA DLA BIEGACZY... Trigger Race 2016 40 Kurtki puchowe/ Przegląd 24 Jacob Snochowski Kurtki z syntetycznymi ocieplinami Ronda dels Cims 2018 42 / Przegląd 25 Andrzej Kowalik Prezentujemy: Columbia / Kurtka 44 27 Ciepłolubna, która kocha zimę! Caldorado II Insulated Monia Wsuł 46 Syntetyczne ociepliny 48 73 61 96 65 48 ¡VAMOS! ¡VAMOS! 73 DEBIUTANCI Wywiad z José Antonio -

100 Marathon Club Roster 08-01-20

100 MARATHON CLUB NORTH AMERICA Founded March 31, 2001 by Bob and Lenore Dolphin MEMBERSHIP ROSTER Updated: August 1, 2020 ! Director: Ron Fowler EMail roster updates to: [email protected] NOTICE: Given the on-going, worldwide Covid-19 pandemic, we are suspending updating of the club's on-line roster and production of the monthly newsletter. Ron Fowler, August 1, 2020 NAME ST CITY AGE M # EVENT LOCATION DATE ACHIEVEMENTS Adair, Tom GA Alpharetta 68 1 Atlanta Marathon Atlanta, GA 11/19/1994 Past President 50 States Marathon Club 100 Atlanta Marathon Atlanta, GA 11/23/2000 Past VP 100 Marathon Club – Japan 200 Hot to Trot 8 Hour Run Atlanta, GA 8/6/2005 7 continents finisher 300 Darkside Marathon Peachtree City, GA 5/25/2009 3 time 50 states finisher 11-2008 in DE Raced 149 consecutive months 1995-2008 Total = 308 marathons as of 12-31-13 Adams, Ron BC North 65 1 Vancouver International Vancouver, BC 5/3/1981 Completed 6 ironman triathlons, Western Vancouver 100 Diez Vista 50K Coquitlam, BC 4/7/2007 States 100 Mile, Knee Knackering North Shore Trail Run 23 times (tied for most) Race director Whistler 50 Mile Ultra PR 2:49:03 set in 1990 at age 41 Aguirre, Andrew OK Tulsa 37 1 Route 66 Marathon Tulsa, OK 11/21/2010 50 states & DC finisher 2017 Honolulu 100 Honolulu Marathon Honolulu, HI 12/10/2017 PR 4:02:30 set in 2015 at age 35 Current total = 77 marathons and 23 ultras Aldous, David CO Denver 59 1 Houston Marathon Houston, TX 1/15/1995 50 states & DC finisher 2015 Maui 100 Salt Lake City Marathon Salt Lake City, UT 4/18/2015 PR 3:51 set in 1996 at age 39 Allen, Herb WA Bainbridge 71 1 Island 100 Yakima River Canyon M.