Open August 1 2013 a Ftp File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intermediate Unit Reporting

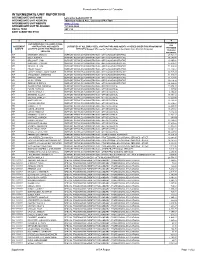

Pennsylvania Department of Education INTERMEDIATE UNIT REPORTING INTERMEDIATE UNIT NAME Lancaster-Lebanon IU 13 INTERMEDIATE UNIT ADDRESS 1020 New Holland Ave., Lancaster PA 17601 INTERMEDIATE UNIT WEBSITE www.iu13.org INTERMEDIATE UNIT TELEPHONE 717-606-1600 FISCAL YEAR 2011-12 DATE SUBMITTED BY IU 2 4 4 4 REMUNERAT LIST INDIVIDUALLY ALL EMPLOYEES, ION AGREEMENT CONTRACTORS AND AGENTS LIST DUTIES OF ALL EMPLOYEES, CONTRACTORS AND AGENTS COVERED UNDER THIS PROGRAM OR PROVIDED NUMBER COVERED UNDER THIS PROGRAM OR SERVICES (Suggest IU's use the Function/Object description from Chart of Accounts) TO EACH SERVICES INDIVIDUAL 954 BARNHART, BRIAN D SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 27,721.14 954 BILLY, SUSAN A SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 38,546.40 954 BRILLHART, GINA SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 13,695.84 954 BURKHART, CYNTHIA SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 35,839.01 954 FIGURELLE, LISA SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 71,929.68 954 FINLEY, MOLLY SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 118,130.64 954 JANNEY SCHALL, DIANE MARIE SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 34,727.28 954 SKRODINSKY, CHRISTINE SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 51,545.33 954 SPINNER, ANN SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 16,728.48 954 WILEY, DEBRA SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION - OFFICIAL/ADMINISTRATIVE 39,116.16 954 ZUBECK, SHERRY D SUPPORT SERVICES-ADMINISTRATION -

Notices Governor's Office

4493 NOTICES • Calabro v. Department of Aging, 689 A.2d 34 (Pa GOVERNOR’S OFFICE Commw. 1997). Catalog of Nonregulatory Documents • Calabro v. Department of Aging, 698 A.2d 596 (Pa. 1997). Under Executive Order 1996-1, agencies under the • Schaffren v. Philadelphia Corporation for Aging, 1997 jurisdiction of the Governor must catalog and publish U.S. Dist. Lexis 17493 (M.D. Pa., 1997). nonregulatory documents such as policy statements, guid- • ance manuals, decisions, rules and other written materi- Scanlon v. Department of Aging, 739 A.2d 635 (Pa. als that provide compliance related information. The Commw. 1999). following compilation is the nineteenth list of the • Nixon v. Comm. of PA, 789 A.2d 376 (Pa. Commw. nonregulatory documents. This list is updated and pub- 2001), affirmed by 576 Pa. 385 (Pa. 2003). lished annually on the first Saturday in August. • Peek v. Department of Aging, 873 A.2d (Pa. Commw. This catalog is being provided to ensure that the public 2005). has complete access to the information necessary to • Silo v. Commonwealth, 886 A.2d 1193 (Pa. Commw. understand and comply with State regulations. We have 2005). made every effort to ensure that the catalog includes all • documents in effect as of July 22, 2015; however, due to Commonwealth v. TAP Pharmaceutical Products, Inc., the breadth and changing nature of these documents, we 885 A.2d 1127 (Pa. Commw. 2005). cannot guarantee absolute accuracy. Facilitating access to • Christian Street Pharmacy v. Department of Aging— information is important to enhancing the partnership unreported Commonwealth Court Opinion—May 30, between the regulated community and the State. -

Solanco School District Lancaster County, Pennsylvania ______

LIMITED PROCEDURES ENGAGEMENT ____________ Solanco School District Lancaster County, Pennsylvania ____________ December 2017 Dr. Brian A. Bliss, Superintendent Mr. Steven P. Risk, Board President Solanco School District Solanco School District 121 South Hess Street 121 South Hess Street Quarryville, Pennsylvania 17566 Quarryville, Pennsylvania 17566 Dear Dr. Bliss and Mr. Risk: We conducted a Limited Procedures Engagement (LPE) of the Solanco School District (District) to determine its compliance with certain relevant state laws, regulations, policies, and administrative procedures (relevant requirements). The LPE covers the period July 1, 2012, through June 30, 2016, except for any areas of compliance that may have required an alternative to this period. The engagement was conducted pursuant to authority derived from Article VIII, Section 10 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and The Fiscal Code (72 P.S. §§ 402 and 403), but was not conducted in accordance with Government Auditing Standards issued by the Comptroller General of the United States. As we conducted our LPE procedures, we sought to determine answers to the following questions, which serve as our LPE objectives: • Did the District have documented board policies and administrative procedures related to the following? o Internal controls o Budgeting practices o The Right-to-Know Law o The Sunshine Act • Were the policies and procedures adequate and appropriate, and have they been properly implemented? • Did the District comply with the relevant requirements in the Right-to-Know Law and the Sunshine Act? Our engagement found that the District properly implemented policies and procedures for the areas mentioned above and complied, in all significant respects, with relevant requirements. -

LAMPETER-STRASBURG SCHOOL DISTRICT Lampeter, Pennsylvania 17537 April 4, 2016

LAMPETER-STRASBURG SCHOOL DISTRICT Lampeter, Pennsylvania 17537 April 4, 2016 A G E N D A Meeting Called to Order Introduction of Guests Opportunity for Public Comment regarding Agenda Items Approval of Minutes of Previous Meetings Communications and Recognition Treasurer's Report – Mr. Terry L. Sweigart Academic Committee – Mrs. Patricia M. Pontz, Chairperson Buildings and Grounds Committee – Mrs. Melissa S. Herr, Chairperson Board of Review Committee – Mr. Jeffrey A. Mills, Chairperson Finance Committee – Mr. Scott J. Kimmel, Chairperson Personnel Committee – Mr. Scott M. Arnst, Chairperson Federal Programs – Dr. Andrew M. Godfrey, Representative Liaison Reports Student Representatives – Miss Chelsea Hancock, Miss McKenna Kimmel Superintendent's Report Old Business New Business Opportunity for Public Comment Adjournment LAMPETER-STRASBURG SCHOOL DISTRICT Lampeter, Pennsylvania 17537 April 4, 2016 LAMPETER-STRASBURG HIGH SCHOOL – Mr. Eric D. Spencer, Principal A. AGRICULTURE The Garden Spot FFA would like to thank the Board for all that they do for the School District and for the students of agriculture courses. The Garden Spot FFA held its annual banquet on March 17, 2016, in the Martin Meylin Middle School cafeteria with approximately 216 members, parents, and guests present. Awards were given to a number of FFA members and community members. PA Secretary of Agriculture Russell Redding and PA State FFA Chaplain Johnathan Noss each gave a speech at the beginning of the banquet. Students also presented speeches on what they have accomplished -

Honors and Awards Convocation

Honors and Awards Convocation MILLERSVILLE UNIVERSITY FIFTY-NINTH ANNUAL SATURDAY THE TWENTY-EIGHTH OF OCTOBER TWO THOUSAND SEVENTEEN AT ELEVEN A.M. STUDENT Memorial CENTER Marauder Courts MILLERSVILLE UNIVERSITY MILLERSVILLE, Pennsylvania 1 Honors and Awards Convocation Vilas A. Prabhu, Ph.D., Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs Presiding PRELUDE MARAUDER MEN’S GLEE CLUB ALLEN C. HOWELL, Ph.D. Director WELCOME DR. PRABHU SALUTATIONS From the Faculty MEHMET I. GOKSU, Ph.D. Professor of Physics From Student Senate KIEFER R. LUCKENBILL ’18 President RECOGNITION OF ALUMNI AWARDS MICHAEL K. HENRY ’83 President Millersville University Alumni Association Distinguished Alumnus Award DUANE E. HAGELGANS ’98, J.D. Honorary Alumnus Award JOHN R. WRIGHT JR., Ph.D., CSTM, F.ATMAE Outstanding Volunteer Service Award LORI LAZARCHICK DIEROLF ’91 Young Alumni Achievement Award ERIN L. BAKER ’03 Young Alumni Achievement Award ASHLEA RINEER-HERSHEY ’03, Ph.D. Young Alumni Achievement Award MICHAEL J. ZDILLA ’00, Ph.D. Please silence cell phones and all electronic devices during the ceremony. Thank you. 2 PRESENTATION OF ACADEMIC HONORS & AWARDS BRANT D. SCHULLER, MFA Professor of Art and Design LAURIE B. HANICH, Ph.D. Professor of Educational Foundations STEVEN M. KENNEDY, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Chemistry MICHELE B. SANTAMARIA Assistant Professor of Learning Design Librarian REMARKS JOHN M. ANDERSON, Ph.D. President, Millersville University CONCLUSION DR. PRABHU *THE ALMA MATER MARAUDER MEN’S GLEE CLUB *Audience will stand Audience Note: For a full listing of the awards presented today, please visit www.millersville.edu/ha-program. Those students who receive more than one award will be presented with all their awards at one time. -

Lancaster Law Review the Official Legal Periodical of Lancaster County ______Vol

Lancaster Law Review The Official Legal Periodical of Lancaster County _____________________________________________________________________ Vol. 95 LANCASTER, PA JUNE 18, 2021 No. 25 _____________________________________________________________________ CASES REPORTED Commonwealth v. Rajeem Brown —No. 2722-2019 — Ashworth, P.J. — May 14, 2021 — Motion to Suppress — Search Warrant — Probable Cause — Staleness — Totality of the Circumstances LEGAL NEWS LEGAL NOTICES Calendar of Events.........................4 Articles of Incorporation Continuing Legal Education Notices............................................31 Calendar...........................................5 Change of Name Notices..............31 LBA Updates...................................7 Estate and Trust Notices...............20 Notice of Volunteer Fictitious Name Notices...............31 Opportunity.....................................9 Miscellaneous Legal Notices.......32 Suits Entered..................................33 LANCASTER LAW REVIEW (USPS 304-080) The Official Legal Periodical of Lancaster County— Reporting the Decisions of the Courts of Lancaster County OWNED AND PUBLISHED BY LANCASTER BAR ASSOCIATION 2021 2021 LBA CONTACTS, SECTION & COMMITTEE CHAIRS Lancaster Bar Association www.lancasterbar.org 28 East Orange Street Phone: 717-393-0737 Lancaster, PA 17602 Fax: 717-393-0221 LANCASTER BAR ASSOCIATION - STAFF Executive Director Lawyer Referral Service Coordinator Lisa Driendl-Miller Cambrie Miller [email protected] [email protected] Managing Editor -

SOLANCO REGIONAL COMPREHENSIVE PLAN August 2009

SOLANCO REGIONAL COMPREHENSIVE PLAN August 2009 DRUMORE TOWNSHIP EAST DRUMORE TOWNSHIP FULTON TOWNSHIP LITTLE BRITAIN TOWNSHIP Prepared by: SOLANCO REGIONAL COMPREHENSIVE PLAN ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Drumore Township Board of Supervisors Drumore Township Planning Commission Kolin D. McCauley, Chairman David Nichols, Chairman James L. Tollinger, Vice-Chairman Robert Currey, Vice-Chairman James A Wingler Ann Zemsky, Secretary Karen McComsey East Drumore Township Board of Thomas Smith Supervisors East Drumore Township Planning V. Merril Carter, Chairman Commission Scott Kreider, Vice-Chairman James E. Landis, Secretary-Treasurer P. Robert Wenger, Chairman Ruth Gentry, Vice-Chair Fulton Township Board of Supervisors Denise Mellott Gary Akers Glenn D. Aument, Chairman Carl Troop Paul Hannum, Vice Chairman William H. Taylor Fulton Township Planning Commission Little Britain Township Board of Gary Kennedy, Chairman Supervisors Carole Huber, Secretary Roy Falcone Gregory D. Culler, Chairman David Spangler, Jr. Randy Jackson, Vice-Chairman Donald Tucker David I. Eller Jerry Emling Little Britain Township Planning Jeffrey O. Wood Commission Solanco Regional Comprehensive Plan Matt Young, Chairman Steering Committee Elaine Craig, Vice-Chair Jim Bullitt Lancaster County Planning Commission Clark Coates Ronald Criswell RETTEW Associates, Consultant William Mingle John Sensenig Acknowledgements August 2009 SOLANCO REGIONAL COMPREHENSIVE PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1: Executive Summary Overview …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Implementation ……………………………………………………………………………………………. -

2019 PURTA Properties

parcel_number status owner address1 address2 city state_code zip_code land_use school district municipality assessed_value 0101463900000 ACTIVE DENVER & EPHRATA TELEPHONE C 130 E MAIN ST EPHRATA PA 17522 TELEPHONE&TELEGRAPH COCALICO SCHOOL DISTRICT ADAMSTOWN BORO 71600 0208075000000 ACTIVE DENVER & EPHRATA TELEPHONE C 130 E MAIN ST EPHRATA PA 17522 TELEPHONE&TELEGRAPH EPHRATA AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT AKRON BORO 162100 0301296700000 ACTIVE PECO ENERGY COMPANY 46 PUBLIC SQUARE P O BOX 8699 PHILADELPHIA PA 19101 ELECTRIC UTILITY SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 50400 0303171300000 ACTIVE PECO ENERGY COMPANY 46 PUBLIC SQUARE P O BOX 8699 PHILADELPHIA PA 19101 TRANS/UTILITY VACANT SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 90400 0304136600000 ACTIVE PECO ENERGY COMPANY 46 PUBLIC SQUARE P O BOX 8699 PHILADELPHIA PA 19101 ELECTRIC UTILITY SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 6400 0304326300000 ACTIVE P P & L INC 2 N 9TH ST ALLENTOWN PA 18101 ELECTRIC UTILITY SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 104000 0304375100000 ACTIVE P P & L INC 2 N 9TH ST ALLENTOWN PA 18101 TRANS/UTILITY VACANT SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 77000 0304721400000 ACTIVE PECO ENERGY COMPANY 46 PUBLIC SQUARE P O BOX 8699 PHILADELPHIA PA 19101 ELECTRIC UTILITY SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 105000 0304939100000 ACTIVE P P & L INC 2 N 9TH ST ALLENTOWN PA 18101 ELECTRIC UTILITY SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 99800 0304939800000 ACTIVE P P & L INC 2 N 9TH ST ALLENTOWN PA 18101 ELECTRIC UTILITY SOLANCO SCHOOL DISTRICT BART TWP 112000 0305093400000 ACTIVE P P & L INC 2 N 9TH ST ALLENTOWN PA 18101 -

Assistance for Students and Families Without Home Internet April 2020

Assistance for Students and Families without Home Internet April 2020 The Steinman Foundation and Lancaster STEM Alliance have partnered with Lancaster-Lebanon Intermediate Unit 13 (IU13), school district Technology Coordinators, Comcast and other Internet providers to offer home Internet assistance at no cost for up to six months! DON’T LET YOUR CHILDREN FALL BEHIND ACADEMICALLY BECAUSE THEY CAN’T ATTEND SCHOOL ONLINE! Here’s how you can apply: Step 1: If you live in an area served by Comcast, sign up for the Internet Essentials program before June 30, 2020. You can do this today at InternetEssentials.com or by calling 855-846-8376. If you are eligible for this program, you will receive six months of free broadband Internet plus an additional six months of Internet for $9.95 a month! This will give you a full year of broadband Internet for under $60. Families in Columbia School District, the School District of Lancaster, La Academia Partnership Charter School, Leola Elementary School, Donegal Intermediate School and Lampeter Elementary School automatically meet income guidelines. Step 2: If, for any reason, you do not qualify for the Internet Essentials program, contact your local school district Technology Coordinator who has funds to help you find another Internet solution. Names and contact numbers are included on the back of this flyer. Please keep documentation that you have been rejected for the Internet Essentials program or that you live in an area not served by Comcast. MAKE SURE YOUR CHILDREN HAVE THE TOOLS THEY NEED TO LEARN -

Part 2 11-07-07 30-07-07 03-07-09 14-07-06 31-07-20 08-07-15 24-07-14 32-07-07 09-07-14 27-07-09 Ch

4285 NOTICES • Peek v. Department of Aging, 873 A.2d (Pa. Commw. GOVERNOR’S OFFICE 2005). Catalog of Nonregulatory Documents • Silo v. Commonwealth, 886 A.2d 1193 (Pa. Commw. 2005). Under Executive Order 1996-1, agencies under the • jurisdiction of the Governor must catalog and publish Commonwealth v. TAP Pharmaceutical Products, Inc., nonregulatory documents such as policy statements, guid- 885 A.2d 1127 (Pa. Commw. 2005). ance manuals, decisions, rules and other written materi- • Christian Street Pharmacy v. Department of Aging— als that provide compliance related information. The unreported Commonwealth Court Opinion—May 30, following compilation is the fifteenth list of the 2007. nonregulatory documents. This list is updated and pub- • lished annually on the first Saturday in August. Christian Street Pharmacy v. Pa. Department of Aging, 946 A.2d 798 (Pa. Commonwealth Court, April 10, This catalog is being provided to ensure that the public 2008). has complete access to the information necessary to • understand and comply with state regulations. We have Commonwealth v. TAP Pharmaceutical Products, et al., made every effort to ensure that the catalog includes all 212 MD 2004 documents in effect as of August 7, 2010; however, due to • Commonwealth v. Janssen Pharmaceutical Inc. Phila- the breadth and changing nature of these documents, we delphia Court of Common Pleas, Case #002181 cannot guarantee absolute accuracy. Facilitating access to information is important to enhancing the partnership INTERNAL GUIDELINES: between the regulated -

October 4, 2014 (Pages 6195-6542)

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 44 (2014) Repository 10-4-2014 October 4, 2014 (Pages 6195-6542) Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2014 Recommended Citation Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, "October 4, 2014 (Pages 6195-6542)" (2014). Volume 44 (2014). 40. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2014/40 This October is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Bulletin Repository at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 44 (2014) by an authorized administrator of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Volume 44 Number 40 Saturday, October 4, 2014 • Harrisburg, PA Pages 6195—6542 See Part II page 6315 for the Governor’s Office’s Part I Catalog of Nonregulatory Agencies in this issue Documents Notice The Courts Department of Banking and Securities See Part III page 6473 Department of Education for the Subject Index for Department of Environmental Protection January—September 2014 Department of Health Department of Revenue Department of State Department of Transportation Executive Board Governor’s Office Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Office of Attorney General Office of Open Records Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission Detailed list of contents appears inside. Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporter (Master Transmittal Sheet): Pennsylvania Bulletin Pennsylvania No. 479, October -

School Board Minutes

UPPER ST CLAIR SCHOOL DISTRICT BOARD OF SCHOOL DIRECTORS Mr. Patrick A. Hewitt, President • Mr. Phillip J. Elias, Vice President • Mrs. Amy L Billerbeck Mrs. Barbara L. Bolas • Mrs. Jennifer L. Bowen • Dr. Daphna Gans • Mr. Louis P. Mafrice, Jr. Mrs. Angela B. Petersen • Mrs. Jennifer A. Schnore Dr. John T. Rozzo, Superintendent • Mrs. Jocelyn P. Kramer, Solicitor SCHOOL BOARD MEETING MINUTES Monday, January 25, 2021 @ 7:00pm Executive Session @ 6:00pm (Personnel and Legal Matters) District Administration Building Board Room Notice having been advertised and posted and members duly notified, a Board Meeting of the Board of School Directors was held on January 25, 2021 in the District Administration Room. School Board Members in Attendance: Mr. Phillip J. Elias, Vice President (in-person) Mrs. Amy Billerbeck (virtual) Mrs. Barbara L. Bolas (in-person) Mrs. Jennifer L. Bowen (virtual) Dr. Daphna Gans (virtual) Mr. Louis P. Mafrice Jr. (virtual) Mrs. Angela Petersen (in-person) Mrs. Jennifer Schnore (virtual) School Personnel in Attendance: Dr. John T. Rozzo, Superintendent (in-person) Dr. Sharon K. Suritsky, Assistant/Deputy Superintendent (virtual) Mrs. Amy Pfender, Assistant to the Superintendent (in-person) Mr. Ray Carson, Senior Director of Operations & Administrative Services (in-person) Mr. Scott Burchill, Director of Business & Finance (in-person) Dr. Lou Angelo, Director of Facilities and Operations (virtual) Mr. Raymond Berrott, Director of Technology (in-person) Dr. Judith Bulazo, Director of Curriculum and Development (virtual) Mrs. Cassandra Doggrell, Director of Student Support Services (virtual) Mrs. Lauren Madia, Assistant Director of Student Support Services (in-person) Mr. Bradley Wilson, Director of Strategic Initiatives (virtual) Mrs.