Mnemonic Devices and Natural Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory

The Integrated Nature of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky and Robert A. Bjork Introduction Memory has been of interest to scholars and laypeople alike for over 2,000 years. In a rather gruesome example from antiquity, Cicero tells the story of Simonides (557– 468 BC), who discovered the method of loci, which is a powerful mental mnemonic for enhancing one’s memory. Simonides was at a banquet of a nobleman, Scopas. To honor him, Simonides sang a poem, but to Scopas’s chagrin, the poem also honored two young men, Castor and Pollux. Being upset, Scopas told Simonides that he was to receive only half his wage. Simonides was later called from the banquet, and legend has it that the banquet room collapsed, and all those inside were crushed. To help bereaved families identify the victims, Simonides reportedly was able to name every- one according to the place where they sat at the table, which gave him the idea that order brings strength to our memories and that to employ this ability people “should choose localities, then form mental images of things they wanted to store in their memory, and place these in the localities” (Cicero, 2001). Tis example highlights an early discovery that has had important applied impli- cations for improving the functioning of memory (see, e.g., Yates, 1997). Memory theory was soon to follow. Aristotle (385–322 BC) claimed that memory arises from three processes: Events are associated (1) through their relative similarity or (2) rela- tive dissimilarity and (3) when they co-occur together in space and time. -

Mnemonics in a Mnutshell: 32 Aids to Psychiatric Diagnosis

Mnemonics in a mnutshell: 32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis Clever, irreverent, or amusing, a mnemonic you remember is a lifelong learning tool ® Dowden Health Media rom SIG: E CAPS to CAGE and WWHHHHIMPS, mnemonics help practitioners and trainees recall Fimportant lists (suchCopyright as criteriaFor for depression,personal use only screening questions for alcoholism, or life-threatening causes of delirium, respectively). Mnemonics’ effi cacy rests on the principle that grouped information is easi- er to remember than individual points of data. Not everyone loves mnemonics, but recollecting diagnostic criteria is useful in clinical practice and research, on board examinations, and for insurance reimbursement. Thus, tools that assist in recalling di- agnostic criteria have a role in psychiatric practice and IMAGES teaching. JUPITER In this article, we present 32 mnemonics to help cli- © nicians diagnose: • affective disorders (Box 1, page 28)1,2 Jason P. Caplan, MD Assistant clinical professor of psychiatry • anxiety disorders (Box 2, page 29)3-6 Creighton University School of Medicine 7,8 • medication adverse effects (Box 3, page 29) Omaha, NE • personality disorders (Box 4, page 30)9-11 Chief of psychiatry • addiction disorders (Box 5, page 32)12,13 St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center Phoenix, AZ • causes of delirium (Box 6, page 32).14 We also discuss how mnemonics improve one’s Theodore A. Stern, MD Professor of psychiatry memory, based on the principles of learning theory. Harvard Medical School Chief, psychiatric consultation service Massachusetts General Hospital How mnemonics work Boston, MA A mnemonic—from the Greek word “mnemonikos” (“of memory”)—links new data with previously learned information. -

Types of Memory and Models of Memory

Inf1: Intro to Cognive Science Types of memory and models of memory Alyssa Alcorn, Helen Pain and Henry Thompson March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 1 1. In the lecture today A review of short-term memory, and how much stuff fits in there anyway 1. Whether or not the number 7 is magic 2. Working memory 3. The Baddeley-Hitch model of memory hEp://www.cartoonstock.com/directory/s/ short_term_memory.asp March 21, 2012 Intro to Cognitive Science 2 2. Review of Short-Term Memory (STM) Short-term memory (STM) is responsible for storing small amounts of material over short periods of Nme A short Nme really means a SHORT Nme-- up to several seconds. Anything remembered for longer than this Nme is classified as long-term memory and involves different systems and processes. !!! Note that this is different that what we mean mean by short- term memory in everyday speech. If someone cannot remember what you told them five minutes ago, this is actually a problem with long-term memory. While much STM research discusses verbal or visuo-spaal informaon, the disNncNon of short vs. long-term applies to other types of sNmuli as well. 3/21/12 Intro to Cognitive Science 3 3. Memory span and magic numbers Amount of informaon varies with individual’s memory span = longest number of items (e.g. digits) that can be immediately repeated back in correct order. Classic research by George Miller (1956) described the apparent limits of short-term memory span in one of the most-cited papers in all of psychology. -

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory Richard Topolski ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Sarah R. Daniel ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Introduction methodology for measuring EM largely independent of semantic memory. Episodic memory (EM) is composed of personally experienced events in which ‘the what, where, and when’ Method are essential components while semantic memory is simply composed of accumulated facts about the world (Tulving, Happy, neutral, or sad mood states were induced in 88 2002). A wide variety of tasks have been used to tap students via a 20 minute long viewing of either a stand-up episodic memory including: recalling words from an early comedy routine, a documentary, or holocaust footage. learned list; yes-no recognition of previously presented Immediately following the mood induction, participants common objects or pictures; and free recall of past personal engaged in eight interactive tasks which involved both experiences. These tasks are used to evaluate episodic familiar objects (pennies and paperclips) and novel memory because in order to know which words, pictures, or geometric forms created by bending paper clips with blue experiences to retrieve, some contextual (episodic) beads into unique shapes, (Rock, Schreilber, and Ro, 1994). information must first be accessed (Mayes & Roberts, A four-item force-choice recognition test for the novel 2001). While all of these measures seem to share this geometric forms was employed, with the task name serving contextual component, none adequately examines the as the retrieval cue. -

Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Evolution of Metacognition

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 29 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Handbook of Metamemory and Memory John Dunlosky, Robert A. Bjork Evolution of Metacognition Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203805503.ch3 Janet Metcalfe Published online on: 28 May 2008 How to cite :- Janet Metcalfe. 28 May 2008, Evolution of Metacognition from: Handbook of Metamemory and Memory Routledge Accessed on: 29 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203805503.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Evolution of Metacognition Janet Metcalfe Introduction The importance of metacognition, in the evolution of human consciousness, has been emphasized by thinkers going back hundreds of years. While it is clear that people have metacognition, even when it is strictly defined as it is here, whether any other animals share this capability is the topic of this chapter. -

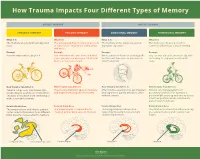

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Hippocampal–Caudate Nucleus Interactions Support Exceptional Memory Performance

Brain Struct Funct DOI 10.1007/s00429-017-1556-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Hippocampal–caudate nucleus interactions support exceptional memory performance Nils C. J. Müller1 · Boris N. Konrad1,2 · Nils Kohn1 · Monica Muñoz-López3 · Michael Czisch2 · Guillén Fernández1 · Martin Dresler1,2 Received: 1 December 2016 / Accepted: 24 October 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Participants of the annual World Memory competitive interaction between hippocampus and caudate Championships regularly demonstrate extraordinary mem- nucleus is often observed in normal memory function, our ory feats, such as memorising the order of 52 playing cards findings suggest that a hippocampal–caudate nucleus in 20 s or 1000 binary digits in 5 min. On a cognitive level, cooperation may enable exceptional memory performance. memory athletes use well-known mnemonic strategies, We speculate that this cooperation reflects an integration of such as the method of loci. However, whether these feats the two memory systems at issue-enabling optimal com- are enabled solely through the use of mnemonic strategies bination of stimulus-response learning and map-based or whether they benefit additionally from optimised neural learning when using mnemonic strategies as for example circuits is still not fully clarified. Investigating 23 leading the method of loci. memory athletes, we found volumes of their right hip- pocampus and caudate nucleus were stronger correlated Keywords Memory athletes · Method of loci · Stimulus with each other compared to matched controls; both these response learning · Cognitive map · Hippocampus · volumes positively correlated with their position in the Caudate nucleus memory sports world ranking. Furthermore, we observed larger volumes of the right anterior hippocampus in ath- letes. -

Memory-Modulation: Self-Improvement Or Self-Depletion?

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY published: 05 April 2018 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00469 Memory-Modulation: Self-Improvement or Self-Depletion? Andrea Lavazza* Neuroethics, Centro Universitario Internazionale, Arezzo, Italy Autobiographical memory is fundamental to the process of self-construction. Therefore, the possibility of modifying autobiographical memories, in particular with memory-modulation and memory-erasing, is a very important topic both from the theoretical and from the practical point of view. The aim of this paper is to illustrate the state of the art of some of the most promising areas of memory-modulation and memory-erasing, considering how they can affect the self and the overall balance of the “self and autobiographical memory” system. Indeed, different conceptualizations of the self and of personal identity in relation to autobiographical memory are what makes memory-modulation and memory-erasing more or less desirable. Because of the current limitations (both practical and ethical) to interventions on memory, I can Edited by: only sketch some hypotheses. However, it can be argued that the choice to mitigate Rossella Guerini, painful memories (or edit memories for other reasons) is somehow problematic, from an Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Italy ethical point of view, according to some of the theories of the self and personal identity Reviewed by: in relation to autobiographical memory, in particular for the so-called narrative theories Tillmann Vierkant, University of Edinburgh, of personal identity, chosen here as the main case of study. Other conceptualizations of United Kingdom the “self and autobiographical memory” system, namely the constructivist theories, do Antonella Marchetti, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, not have this sort of critical concerns. -

CHAPTER 6: MEMORY STRATEGIES: MNEMONIC DEVICES in Order to Remember Information, You First Have to Find It Somewhere in Your Memory

CHAPTER 6: MEMORY STRATEGIES: MNEMONIC DEVICES In order to remember information, you first have to find it somewhere in your memory. To be successful in college you need to use active learning strategies that help you store information and retrieve it. Mnemonic devices can help you do that. Mnemonics are techniques for remembering information that is otherwise difficult to recall. The idea behind using mnemonics is to encode complex information in a way that is much easier to remember. Two common types of mnemonic devices are acronyms and acrostics. Acronyms Acronyms are words made up of the first letters of other words. As a mnemonic device, acronyms help you remember the first letters of items in a list, which in turn helps you remember the list itself. Instructor OLC to accompany 100% Online Student Success 1 Examples The following are examples of popular mnemonic acronyms: HOMES Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior Names of the Great Lakes FACE The letters of the treble clef notes in the spaces from bottom to top spells “FACE”. ROY G. BIV Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Colors of the spectrum Violet MRS GREN Movement, Respiration, Sensitivity, Growth, Common attributes of living Reproduction, Excretion, Nutrition things Create Your Own Acronym Now think of a few words you need to remember. This could be related to your studies, your work, or just a subject of interest. Five steps to creating acronyms are*: 1. List the information you need to learn in meaningful phrases. 2. Circle or underline a keyword in each phrase. 3. Write down the first letter of each keyword. -

Episodic Memory-From Brain to Mind

HIPPOCAMPUS 16:691–703 (2006) Episodic Memory—From Brain to Mind Janina Ferbinteanu,* Pamela J. Kennedy, and Matthew L. Shapiro ABSTRACT: Neuronal mechanisms of episodic memory, the conscious by the rapid formation of relational representations of recollection of autobiographical events, are largely unknown because highly processed sensory information that are used electrophysiological studies in humans are conducted only in excep- tional circumstances. Unit recording studies in animals are thus crucial flexibly and are not necessarily expressed through overt for understanding the neurophysiological substrate that enables people motor behavior. Episodic memory is also sensitive to to remember their individual past. Two features of episodic memory— lesions of the prefrontal cortex (Wheeler et al., 1995; autonoetic consciousness, the self-aware ability to \travel through Nyberg et al., 2000; Burgess et al., 2002; Wheeler time", and one-trial learning, the acquisition of information in one and Stuss, 2003), develops later in an individual’s life, occurrence of the event—raise important questions about the validity of animal models and the ability of unit recording studies to capture essen- encodes events within a personal framework, and pos- tial aspects of memory for episodes. We argue that autonoetic experi- sesses a temporal dimension because it is oriented ence is a feature of human consciousness rather than an obligatory as- towards the past and the future (Tulving, 1972, 2001, pect of memory for episodes, and that episodic memory is reconstruc- 2002; Tulving and Markowitsch, 1998). Autobio- tive and thus its key features can be modeled in animal behavioral tasks graphic information contains memories about what that do not involve either autonoetic consciousness or one-trial learning. -

Learning Styles and Memory

Learning Styles and Memory Sandra E. Davis Auburn University Abstract The purpose of this article is to examine the relationship between learning styles and memory. Two learning styles were addressed in order to increase the understanding of learning styles and how they are applied to the individual. Specifically, memory phases and layers of memory will also be discussed. In conclusion, an increased understanding of the relationship between learning styles and memory seems to help the learner gain a better understanding of how to the maximize benefits for the preferred leaning style and how to retain the information in long-term memory. Introduction Learning styles, as identified in the Perpetual Learning Styles Theory and memory, as identified in the Memletics Accelerated Learning, will be overviewed. Factors involving information being retained into memory will then be discussed. This article will explain how the relationship between learning styles and memory can help the learner maximize his or her learning potential. Learning Styles The Perceptual Learning Styles Theory lists seven different styles. They are print, aural, interactive, visual, haptic, kinesthetic, and olfactory (Institute for Learning Styles Research, 2003). This theory says that most of what we learn comes from our five senses. The Perceptual Learning Style Theory defines the seven learning styles as follows: The print learning style individual prefers to see the written word (Institute for Learning Styles Research, 2003). They like taking notes, reading books, and seeing the written word, either on a chalk board or thru a media presentation such as Microsoft Powerpoint. The aural learner refers to listening (Institute for Learning Styles Research, 2003).