Hasbro Interactive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Monopolists Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the Worlds Favorite Board Game 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE MONOPOLISTS OBSESSION, FURY, AND THE SCANDAL BEHIND THE WORLDS FAVORITE BOARD GAME 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mary Pilon | 9781608199631 | | | | | The Monopolists Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the Worlds Favorite Board Game 1st edition PDF Book The Monopolists reveals the unknown story of how Monopoly came into existence, the reinvention of its history by Parker Brothers and multiple media outlets, the lost female originator of the game, and one man's lifelong obsession to tell the true story about the game's questionable origins. Expand the sub menu Film. Determined though her research may be, Pilon seems to make a point of protecting the reader from the grind of engaging these truths. More From Our Brands. We logged you out. This book allows a darker side of Monopoly. Cannot recommend it enough! Part journalist, part sleuth, Pilon exhausted five years researching the game's origin. Mary Pilon's page-turning narrative unravels the innocent beginnings, the corporate shenanigans, and the big lie at the center of this iconic boxed board game. For additional info see pbs. Courts slapped Parker Brothers down on those two games, ruling that the games were clearly in the public domain. Subscribe now Return to the free version of the site. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. After reading The Monopolists -part parable on the perils facing inventors, part legal odyssey, and part detective story-you'll never look at spry Mr. Open Preview See a Problem? The book is superlative journalism. Ralph Anspach, a professor fighting to sell his Anti-Monopoly board game decades later, unearthed the real story, which traces back to Abraham Lincoln, the Quakers, and a forgotten feminist named Lizzie Magie who invented her nearly identical Landlord's Game more than thirty years before Parker Brothers sold their version of Monopoly. -

History of the World Rulebook

TM RULES OF PLAY Introduction Components “With bronze as a mirror, one can correct one’s appearance; with history as a mirror, one can understand the rise and fall of a state; with good men as a mirror, one can distinguish right from wrong.” – Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty History of the World takes 3–6 players on an epic ride through humankind’s history. From the dawn of civilization to the twentieth century, you will witness humanity in all its majesty. Great minds work toward technological advances, ambitious leaders inspire their 1 Game Board 150 Armies citizens, and unpredictable calamities occur—all amid the rise and fall (6 colors, 25 of each) of empires. A game consists of five epochs of time, in which players command various empires at the height of their power. During your turn, you expand your empire across the globe, gaining points for your conquests. Forge many a prosperous empire and defeat your adversaries, for at the end of the game, only the player with the most 24 Capitols/Cities 20 Monuments (double-sided) points will have his or her immortal name etched into the annals of history! Catapult and Fort Assembly Note: The lighter-colored sides of the catapult should always face upward and outward. 14 Forts 1 Catapult Egyptians Ramesses II (1279–1213 BCE) WEAPONRY I EPOCH 4 1500–450 BCE NILE Sumerians 3 Tigris – Empty Quarter Egyptians 4 Nile Minoans 3 Crete – Mediterranean Sea Hittites 4 Anatolia During this turn, when you fight a battle, Assyrians 6 Pyramids: Build 1 monument for every Mesopotamia – Empty Quarter 1 resource icon (instead of every 2). -

P Small and See a �Igger Communit

New toy hatches similar ‘must have’ fury Nineties parents were no much as 1,000 percent situation. The stuffed Heather stranger to the “hot toy” more than its purchase dolls were one of the most Harmon craze, after having lived price. popular toy fads of the Staff Reporter through “Elmo-mania” two Today, many of the parents decade, and at the toy’s years prior in 1996. There searching for a Hatchimal height in popularity, parents ne does not have were one millions units may have wanted Cabbage physically fought in stores, to look far to released during the holiday Patch Kids for themselves causing chaos over the find a frantic season, and at the end of in the 1980s, which put cherub-faced dolls. parent searching December the entire stock their parents in a similar The manufacturers of Ofor a Hatchimal for their has been sold-out. Due to Hatchimals have responded child for Christmas. The limited quantities of the to the limited supplies of toy is going for as much School board votes in product, stampedes and the toys and their resale as $500 on Ebay, and have fights broke out at retailers value. been seen on online local who sold the Elmos. The statement reads, swap social media sites for design for visitor stands Beanie babies “ This is a special $300, while they retail for hit the shelves in season and we don’t $59-$69. Heather Harmon 1995, and due to want anyone to be Staff Reporter Although the generation a particularly disappointed, nor of parents and the “hot clever marketing do we support uring their monthly board meeting, the toy of the season” may strategy, the inflated prices from Weatherford Public Schools Board of have changed over the stuffed animals non-authorized Education voted to approve an architect’s years, parents hunting for were highly resellers. -

Speech Sounds Vowels HOPE

This is the Cochlear™ promise to you. As the global leader in hearing solutions, Cochlear is dedicated to bringing the gift of sound to people all over the world. With our hearing solutions, Cochlear has reconnected over 250,000 cochlear implant and Baha® users to their families, friends and communities in more than 100 countries. Along with the industry’s largest investment in research and development, we continue to partner with leading international Speech Sounds:Vowels researchers and hearing professionals, ensuring that we are at the forefront in the science of hearing. A Guide for Parents and Professionals For the person with hearing loss receiving any one of the Cochlear hearing solutions, our commitment is that for the rest of your life in English and Spanish we will be here to support you Hear now. And always Ideas compiled by CASTLE staff, Department of Otolaryngology As your partner in hearing for life, Cochlear believes it is important that you understand University of North Carolina — Chapel Hill not only the benefits, but also the potential risks associated with any cochlear implant. You should talk to your hearing healthcare provider about who is a candidate for cochlear implantation. Before any cochlear implant surgery, it is important to talk to your doctor about CDC guidelines for pre-surgical vaccinations. Cochlear implants are contraindicated for patients with lesions of the auditory nerve, active ear infections or active disease of the middle ear. Cochlear implantation is a surgical procedure, and carries with it the risks typical for surgery. You may lose residual hearing in the implanted ear. -

Taking Intelligence on Board Remembering the “Color” Days I Tama

Childhood toys have touched the lives of many. Some children are even shaped by them as Blast from the games brings back Taking Intelligence On Board memories of precious time For many of us, some of our best childhood moments were defined by spent with loved ones. playing a board game with family members, as we slowly advanced our way through the games. The laughter, sheer joy and closer bonds that each game elicited kept these memories valuable. Throughout the years, board games have become venues the Past through which our genuine selves are revealed, as we respond emotionally and physi- cally to friendly competition. I Tama Got You The oldest known board game, The Royal Game of Ur, was discovered by Sir Leon- Childhood fads come and go, but the memories last forever. An example is Tama- ard Woolley between 1926 and 1927, after a search in the royal tombs of present- gotchi, a convenient pocket-sized digital pet that was first released in Japan in 1996. day Iraq. Today, many board games provide hands-on practice for children, allowing This simple egg-shaped toy became very popular and was mass-produced in the 1990s. In just youngsters to encompass learning experiences before they start kindergarten. Clas- How Much Do You Know over a decade, more than 78 million Tamagotchis were sold worldwide. Nowadays, there are sic board games enable potential students to gain intelligence as they are exposed variations of this handheld gadget with more functions on the market, including the new app to basic reading and math skills, as well as problem solving and critical thinking About Childhood Toys? that was launched by Android in February, shortly followed by Apple and Google Play. -

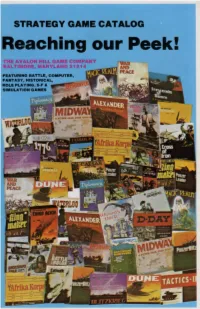

Ah-80Catalog-Alt

STRATEGY GAME CATALOG I Reaching our Peek! FEATURING BATTLE, COMPUTER, FANTASY, HISTORICAL, ROLE PLAYING, S·F & ......\Ci l\\a'C:O: SIMULATION GAMES REACHING OUR PEEK Complexity ratings of one to three are introduc tory level games Ratings of four to six are in Wargaming can be a dece1v1ng term Wargamers termediate levels, and ratings of seven to ten are the are not warmongers People play wargames for one advanced levels Many games actually have more of three reasons . One , they are interested 1n history, than one level in the game Itself. having a basic game partlcularly m1l11ary history Two. they enroy the and one or more advanced games as well. In other challenge and compet111on strategy games afford words. the advance up the complexity scale can be Three. and most important. playing games is FUN accomplished within the game and wargaming is their hobby The listed playing times can be dece1v1ng though Indeed. wargaming 1s an expanding hobby they too are presented as a guide for the buyer Most Though 11 has been around for over twenty years. 11 games have more than one game w1th1n them In the has only recently begun to boom . It's no [onger called hobby, these games w1th1n the game are called JUSt wargam1ng It has other names like strategy gam scenarios. part of the total campaign or battle the ing, adventure gaming, and simulation gaming It game 1s about Scenarios give the game and the isn 't another hoola hoop though. By any name, players variety Some games are completely open wargam1ng 1s here to stay ended These are actually a game system. -

View from the Trenches Avalon Hill Sold!

VIEW FROM THE TRENCHES Britain's Premier ASL Journal Issue 21 September '98 UK £2.00 US $4.00 AVALON HILL SOLD! IN THIS ISSUE HIT THE BEACHES RUNNING - Seaborne assaults for beginners SAVING PRIVATE RYAN - Spielberg's New WW2 Movie LANDING CRAFT FLOWCHART - LC damage determination made easy GOLD BEACH - UK D-Day Convention report IN THIS ISSUE PREP FIRE Hello and welcome the latest issue of View From The Trenches. PREP FIRE 2 The issue is slightly bigger than normal due to Greg Dahl’s AVALON HILL SOLD 3 excellent but rather large article and accompanying flowchart dealing with beach assaults. Four extra pages for the same price. Can’t be INCOMING 4 bad. SCOTLAND THE BRAVE 5 In keeping with the seaborne theme there is also a report on the replaying of the Monster Scenarios ‘Gold Beach’ scenario in the D-DAY AT GOLD BEACH 6 D-Day museum in June, and a review of the new Steve Spielberg WW2 movie, Saving Private Ryan. HIT THE BEACHES RUNNING! 7 I hope to be attending ASLOK this year, so I’m not sure if the “THIS IS THE CALL TO ARMS!” 9 next issue will be out at INTENSIVE FIRE yet. If not, it’ll be out soon after IF’98. THE CRUSADERS 12 While on the subject of conventions, if anyone is planning on SAVING PRIVATE RYAN 18 attending the German convention GRENADIER ’98 please get in touch with me. If we can get enough of us to go as a group, David ON THE CONVENTION TRAIL 19 Schofield may be able to organise transport for all us. -

Playing Purple in Avalon Hill Britannia

Sweep of History Games Magazine #2 Page 1 Sweep of History Games Magazine #2, Spring 2006. Published and edited by Dr. Lewis Pulsipher, [email protected]. This approximately quarterly electronic magazine is distributed free via http://www.pulsipher.net/sweepofhistory/index.htm, and via other outlets. The purpose of the magazine is to entertain and educate those interested in games related to Britannia ("Britannia-like games"), and other games that cover a large geographical area and centuries of time ("sweep of history games"). Articles are copyrighted by the individual authors. Game titles are trademarks of their respective publishers. As this is a free magazine, contributors earn only my thanks and the thanks of those who read their articles. This magazine is about games, but we will use historical articles that are related to the games we cover. This copyrighted magazine may be freely distributed (without alteration) by any not-for-profit mechanism. If you are in doubt, write to the editor/publisher. The “home” format is PDF (saved from WordPerfect); it is also available as unformatted HTML (again saved from WP) at www.pulsipher.net/sweepofhistory/index.htm. Table of Contents strategy article in Issue 1, is one of the “sharks” from the World Boardgaming Championships. 1 Introduction Nick has twice won the Britannia tournament 1 Playing Purple in Avalon Hill there, and is also (not surprisingly) successful at Britannia by Nick Benedict WBC Diplomacy. 7 Britannia by E-mail by Jaakko Kankaanpaa 11 Review of game Mesopotamia: I confess, I’m fascinated to see what strategies the “sharks” will devise for the Second Edition, which by George Van Voorn Birth of Civilisation I understand will be used at this year’s 12 Trying to Define Sweep of History tournament. -

Parker Brothers Real Estate Trading Game in 1934, Charles B

Parker Brothers Real Estate Trading Game In 1934, Charles B. Darrow of Germantown, Pennsylvania, presented a game called MONOPOLY to the executives of Parker Brothers. Mr. Darrow, like many other Americans, was unemployed at the time and often played this game to amuse himself and pass the time. It was the game’s exciting promise of fame and fortune that initially prompted Darrow to produce this game on his own. With help from a friend who was a printer, Darrow sold 5,000 sets of the MONOPOLY game to a Philadelphia department store. As the demand for the game grew, Darrow could not keep up with the orders and arranged for Parker Brothers to take over the game. Since 1935, when Parker Brothers acquired the rights to the game, it has become the leading proprietary game not only in the United States but throughout the Western World. As of 1994, the game is published under license in 43 countries, and in 26 languages; in addition, the U.S. Spanish edition is sold in another 11 countries. OBJECT…The object of the game is to become the wealthiest player through buying, renting and selling property. EQUIPMENT…The equipment consists of a board, 2 dice, tokens, 32 houses and 12 hotels. There are Chance and Community Chest cards, a Title Deed card for each property and play money. PREPARATION…Place the board on a table and put the Chance and Community Chest cards face down on their allotted spaces on the board. Each player chooses one token to represent him/her while traveling around the board. -

Christmas Bureau Distribution Toy Drive Wish List

CHRISTMAS BUREAU DISTRIBUTION TOY DRIVE WISH LIST Newborn - 2 Years VTech Pull and Sing Puppy Sassy Developmental Bumpy Ball Nuby Octopus Hoopla Bathtime Fun Toys, Purple Mega Bloks Caterpillar Lil' Dump Truck Fisher-Price Rock-a-Stack VTech Touch & Swipe Baby Phone VTech Baby Lil' Critters Moosical Beads Oball Shaker Baby Banana Infant Training Toothbrush and Teether, Yellow Fisher - Pri ce Rattle 'n Rock Maracas, Pink/Purple VTech Busy Learners Activity Cube VTech Musical Rhymes Book Bright Baby colors, abc, & numbers first words (First 100) Bright Starts Grab and Spin Rattle First 100 Words Mega Bloks 80-Piece Big Building Bag, Classic Sassy Wonder Wheel Activity Center First 100 Numbers The First Years Stack Up Cups Baby Einstein Take Along Tunes Musical Toy Nuby IcyBite Keys Teether - BPA Free Girls 2 - 5 Years Boys 2 - 5 Years Melissa & Doug Scratch Art Rainbow Mini Notes (125 ct) Fisher-Price Bright Beats Dance & Move BeatBox With Wooden Stylus Kids Bowling Play Set, Safe Foam Bowling Ball Toy LeapFrog Shapes And Sharing Picnic Basket Fisher-Price Rock-a-Stack and Baby's 1st Blocks Bundle Playkidz My First Purse Little Tikes T-Ball Set Play-Doh Sparkle Compound Collection Mega Bloks Block Scooping Wagon Building Set Red ALEX Toys Rub a Dub Princesses in the Tub VTech Busy Learners Activity Cube Lam Wooden Number Puzzle Board Toy Little Tikes Easy Score Basketball Set Puzzled Alphabet Raised Wooden Puzzle for Children Mega Bloks 80-Piece Big Building Bag Aurora World Fancy Pals Plush Pink Pet Carrier Purse with VTech Sit-to-Stand Learning Walker White Pony LEGO Juniors Batman & Superman vs. -

For Immediate Release More Than 400 Word Experts To

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contacts: John D. Williams Jr. (631) 477-0033 ext. 14 (516) 658-7583 (cell) [email protected] Katie Schulz (631) 477-0033 ext. 15 (631) 291-1033 (cell) [email protected] MORE THAN 400 WORD EXPERTS TO COMPETE FOR $10,000 FIRST PRIZE AT NATIONAL SCRABBLE® CHAMPIONSHIP IN DALLAS AUGUST 7-11TH Dallas, TX – They say everything is bigger in Texas, and beginning August 7th, more than 400 people with some of the largest vocabularies in the world will gather at the 2010 National SCRABBLE® Championship (NSC) at the Hotel InterContinental Dallas. These word wizards will come from 42 states and four countries and range from School SCRABBLE prodigies to multiple National and World SCRABBLE® champions. First prize is $10,000 and “bragging rights” for the hundreds of SCRABBLE aficionados who will be descending upon Dallas. “Approximately 40 million people play the SCRABBLE game on a leisurely basis, however SCRABBLE is a lifestyle for our competitors,” says Chris Cree, a veteran top expert and co-president of the North American SCRABBLE® Players Association (NASPA), organizers of this year’s event. There are 200 official SCRABBLE tournaments every year that are overseen by NASPA. -more- Players at the highest level memorize the 120,000 word Official SCRABBLE® Players Dictionary and often devote several hours a day to studying. All the competitors know that the championship will be a marathon, not a sprint. There is no elimination, and everyone plays a staggering 31 games over four and a half days. SCRABBLE experts and enthusiasts everywhere are encouraged to follow the live online coverage at www.scrabbleplayers.org. -

Hasbro, Inc. $300,000,000 2.600% Notes Due 2022 $500,000,000 3.000% Notes Due 2024 $675,000,000 3.550% Notes Due 2026 $900,000,000 3.900% Notes Due 2029

424B2 424B2http://www.oblible.com 1 d823125d424b2.htm 424B2 Table of Contents CALCULATION OF REGISTRATION FEE Title of Each Class of Securities Amount to be Maximum Offering Maximum Aggregate Amount of to be Registered Registered Price Per Unit Offering Price Registration Fee(1) 2.600% Notes due 2022 $300,000,000 99.989% $299,967,000 $38,935.72 3.000% Notes due 2024 $500,000,000 99.811% $499,055,000 $64,777.34 3.550% Notes due 2026 $675,000,000 99.705% $673,008,750 $87,356.54 3.900% Notes due 2029 $900,000,000 99.680% $897,120,000 $116,446.18 Total $2,375,000,000 — $2,369,150,750 $307,515.77 (1) Calculated in accordance with Rule 457(r) under the Securities Act of 1933. Table of Contents Filed pursuant to Rule 424(b)(2) Registration No. 333-220331 PROSPECTUS SUPPLEMENT (To Prospectus dated September 5, 2017) $2,375,000,000 Hasbro, Inc. $300,000,000 2.600% Notes due 2022 $500,000,000 3.000% Notes due 2024 $675,000,000 3.550% Notes due 2026 $900,000,000 3.900% Notes due 2029 Hasbro, Inc. (“Hasbro,” the “Company,” “we” or “us”) is offering $300,000,000 aggregate principal amount of our 2.600% notes due 2022 (the “2022 notes”), $500,000,000 aggregate principal amount of our 3.000% notes due 2024 (the “2024 notes”), $675,000,000 aggregate principal amount of our 3.550% notes due 2026 (the “2026 notes”) and $900,000,000 aggregate principal amount of our 3.900% notes due 2029 (the “2029 notes”).