Regeldokument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Not Worth the Risk” Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’S 2017 Elections

“Not Worth the Risk” Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’s 2017 Elections HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH “Not Worth the Risk” Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’s 2017 Elections Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34761 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa is an independent not-for profit organization that promotes freedom of expression and access to information as a fundamental human right as well as an empowerment right. ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa was registered in Kenya in 2007 as an affiliate of ARTICLE 19 international. ARTICLE 19 Eastern African has over the past 10 years implemented projects that included policy and legislative advocacy on media and access to information laws and review of public service media policies and regulations. The organization has also implemented capacity building programmes for journalists on safety and protection and for a select civil society organisation to engage with United Nations (UN) and African Union (AU) mechanisms in 14 countries in Eastern Africa. -

Kenya Briefing Packet

KENYA PROVIDING COMMUNITY HEALTH TO POPULATIONS MOST IN NEED se P RE-FIELD BRIEFING PACKET KENYA 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org KENYA Country Briefing Packet Contents ABOUT THIS PACKET 3 BACKGROUND 4 EXTENDING YOUR STAY? 5 PUBLIC HEALTH OVERVIEW 7 NATIONAL FLAG 15 COUNTRY OVERVIEW 15 OVERVIEW 16 BRIEF HISTORY OF KENYA 17 GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE AND WEATHER 19 DEMOGRAPHICS 21 ECONOMY 26 EDUCATION 27 RELIGION 29 POVERTY 30 CULTURE 31 USEFUL SWAHILI PHRASES 36 SAFETY 39 CURRENCY 40 IMR RECOMMENDATIONS ON PERSONAL FUNDS 42 TIME IN KENYA 42 EMBASSY INFORMATION 43 WEBSITES 43 !2 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org KENYA Country Briefing Packet ABOUT THIS PACKET This packet has been created to serve as a resource for the KENYA Medical/Dental Team. This packet is information about the country and can be read at your leisure or on the airplane. The first section of this booklet is specific to the areas we will be working near (however, not the actual clinic locations) and contains information you may want to know before the trip. The contents herein are not for distributional purposes and are intended for the use of the team and their families. Sources of the information all come from public record and documentation. You may access any of the information and more updates directly from the World Wide Web and other public sources. !3 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org KENYA Country Briefing Packet BACKGROUND Kenya, located in East Africa, spans more than 224,000 sq. -

KENYA Prep COMMUNICATIONS LANDSCAPE ANALYSIS What Do We Know and What Do We Need to Know?

KENYA PrEP COMMUNICATIONS LANDSCAPE ANALYSIS What do we know and what do we need to know? McCann Global Health Prepared for the Technical Working Group January 27, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS About the 5Cs 8 Culture 12 Consumer 37 Serodiscordant Couples 39 Adolescent Girls & Young Women 57 Men Who Have Sex With Men 81 Female Sex Workers 101 People Who Inject Drugs 120 Health Care Workers 137 Category 159 Connections 186 Company 214 The Competitive Set 240 2 OVERVIEW The Optimizing Prevention Technology Introduction on With support from PrEP TWG, McCann Global Health will Schedule (OPTIONS) consortium is one of five projects conduct a national market intelligence study and support funded by USAID, in partnership with the PEPFAR to the development of a national market preparation and expedite and sustain access to antiretroviral-based HIV communications strategy to support demand creation prevention products by providing technical assistance for efforts of PrEP in Kenya. This strategy aims to offer a investment scenarios, market preparation strategies, cohesive, strategic, and coordinated launch of PrEP as well country-level support, implementation science and health as forthcoming ARV prevention products in Kenya. systems strengthening in countries and among populations Prior to the start of the market intelligence, McCann has where most needed. conducted a landscape analysis of all available A key aim within OPTIONS is to develop a market communications about the target audiences, HIV preparation and communications guide for the prevention, and PrEP in Kenya, to identify key knowledge introduction and uptake of PrEP in Kenya, led by the gaps for further exploration in the market intelligence. -

Urbanization and Adaptation a Reorganization Process of Social

!\ URBANIZATION AND ADAPTATION A Reorganization Process of Social Relations Among The Maragoli Migrants In Their Urban Colony, Kangemi, Nairobi Kenya. By Motoji UDA B . A. , M . A. University of Kyoto, Japan. A Thesis submitted in fulfullment of the requrements for the degree of Master of Arts (SOCIOLOGY) in the University of Nairobi. 1984 . (i) D K C L A R A T I 0 N This Thesis is my original work and had not been presented for a degree in any other University Motoji MATSUDA This Thesis has been submitted for examination with our approval as University Supervisors. DR. B.E. KIPKORIR Former Director of Institute of African Studies . UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI. DR. E. MBOlRyCU DEPARTMENT OF S(3CI0L0GY UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI . (ii) Abstract African urban studies of Anthropology have their origin in one ideal model, the dyachronic model. This model assumes that African urbanization can be regarded as a gradual process of detribali- zation in consequence of direct contact with heterogeneous and powerful Western Cultures. In the 1950's, however, members of Rhodes-Livingstone School advocated a new approach for African urban studies. They criticized the detribalization model and put forward the situational analysis which emphasized synchronic social relations. This approach had a decided superiority because it high lighted the migrant's personal strategy in situafional selection. It cannot, however, explain the retribalization phenomenon which prevails in the most of African larger cities today. It cannot resolve the paradox of retaining tribal relations in a strikingly urban context. There are several points of the situational analysis that requires to be modified. -

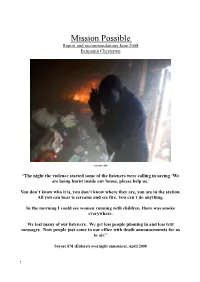

Mission Possible Report and Recommendations June 2008 Benjamin Chesterton

Mission Possible Report and recommendations June 2008 Benjamin Chesterton copyright Chiba “The night the violence started some of the listeners were calling in saying ‘We are being burnt inside our house, please help us.’ You don’t know who it is, you don’t know where they are, you are in the station. All you can hear is screams and see fire. You can’t do anything. In the morning I could see women running with children, there was smoke everywhere. We lost many of our listeners. We get less people phoning in and less text messages. Now people just come to our office with death announcements for us to air.” Sayare FM (Eldoret) overnight announcer, April 2008 1 Contents Part one – The Roundtables 1. Introduction 2. What is Mission Possible? 3. Round tables: Unpacking Kenya. Frameworks for understanding and reporting conflict. Editors’ Seminar Who Turns them On? Presentation for peace. A take on truth. The use, abuse and power of image in the media. 4. Analysis 5. Recommendations Part Two – Mission Possible in the field 1. Introduction 2. Defining and designing the Mission Possible field training 3. Selection of stations 4. Overview of training 5. The Mission Possible training objectives 6. Recommendations 2 Introduction The following report is a write up of Mission Possible, INTERNEWS’ PACT-funded media intervention launched in February 2008, following the post-election violence that gripped Kenya. The title reflects the positive role the media needs to play if a lasting and just peace is to be secured for Kenya. “The media has failed Kenya. -

The Challenges of Reinvigorating Democracy Through Visual Art in 21St Century Nairobi

The challenges of reinvigorating democracy through visual art in 21st century Nairobi Craig Campbell Halliday 30 September 2019 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sainsbury Research Unit for the Arts of Africa, Oceania & the Americas School of Art, Media and American Studies University of East Anglia, Norwich This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 1 Abstract This study examines the potential for contemporary visual art to reinvigorate democracy in 21st century Nairobi, Kenya, through an interdisciplinary investigation. The new millennium ushered in fresh hope for democratisation in the postcolonial East African country. In 2002, Daniel arap Moi’s 24 years of authoritarian rule ended. The opposition were victorious at the ballot box, instilling a belief amongst the electorate that formal political processes could bring change. However, the post-election violence of 2007/8 shattered such convictions. But, from this election result came a progressive Constitution and with it possibilities for creating change. These momentous events underscore Kenya’s topsy-turvy path towards democracy – a path whose trajectory is charted in the experience of ordinary Kenyans who believe in democracy’s value and their right to participate in politics and civil life. Artists, too, have been at the forefront of this ongoing struggle. This study draws on empirical research to demonstrate contemporary visual art’s capacity to expand ways of practising, experiencing and understanding democracy. -

CHEROTICH MUNG'ou.Pdf

THE ROLE OF INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES IN PEACEBUILDING IN MOUNT ELGON REGION, KENYA BY CHEROTICH MUNG’OU A Thesis submitted to the Institute of Postgraduate Studies and Research, in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies of Kabarak University June, 2016 DECLARATION PAGE Declaration I hereby declare that this research thesis is my own original work and to the best of my knowledge has not been presented for the award of a degree in any university or college. Student’s Signature: Student’s Name: Cherotich Mung’ou Registration No: GDE/M/1265/09/11 Date: 30thJune, 2016 i RECOMMENDATION PAGE To the Institute of Postgraduate Studies and Research: The thesis entitled “The Role of Information and Communication Technologies in Peacebuilding in Mt Elgon Region, Kenya” and written by Cherotich Mung’ou is presented to the Institute of Postgraduate Studies and Research of Kabarak University. We have reviewed the thesis and recommend it be accepted in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies. 24th June, 2016 Dr. Tom Kwanya Senior Lecturer, The Technical University of Kenya 30th June, 2016 ____________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Joseph Osodo Lecturer, Maseno University ii Acknowledgement I am greatly indebted to various individuals for the great roles they played throughout my research undertaking. Most importantly, I thank God for the far He has brought me. My first gratitude goes to my supervisors Dr Tom Kwanya and Dr Joseph Osodo for their tireless effort in reviewing my work. I appreciate your intellectual advice and patience. -

NMG-2013-Annual-Report.Pdf

& 2013 Annual Report & Financial Statements 2013 1 Nation Media Group 2 The Nation Media Group, the largest independent media house in East and Central Africa with operations in print, broadcast and digital media, attracts and serves unparalleled audiences in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda Published in 2014 Copyrights © 2013 Nation Media Group Limited All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrivial system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of the copyright holder. 90.4 Omuziki N’ebikuzimba Head Oce P.O. Box 49010 Tel. +254 20 3288000 Nation House 00100, GPO +254 20 221101 Kimathi Street Nairobi, Kenya www.nationmedia.com Browse, download or print our annual report at View our 2013 results presentation at http://www.nationmedia.com/2013 annualreport.pdf http://www.nationmedia.com/docs/2013_Results_Investor_Brieng.pdf Annual Report & Financial Statements 2013 3 BRANDS The Nation Media Group, the largest independent media house in East and Central Africa with operations in print, broadcast and digital media, attracts and serves unparalleled audiences in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda Published in 2014 Copyrights © 2013 Nation Media Group Limited All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrivial system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of the copyright holder. 90.4 -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA Woman As Mother And

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Woman as Mother and Wife in the African Context of the Family in the Light of John Paul II’s Anthropological and Theological Foundation: The Case Reflected within the Bantu and Nilotic Tribes of Kenya A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America For the Degree Doctor of Sacred Theology © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Joseph Okech Adhunga Washington, D. C. 2012 Woman as Mother and Wife in the African Context of the Family in the Light of John Paul II’s Anthropological and Theological Foundation: The Case reflected within the Bantu and Nilotic Tribes of Kenya Joseph Okech Adhunga, S.T.D. Director: Brian V. Johnstone, S.T.D. This study examines the theological and anthropological foundations of the understanding of the dignity and vocation of woman as mother and wife, gifts given by God that expresses the riches of the African concept of family. There are two approaches to inculturation theology in Africa, namely, that which attempts to construct African theology by starting from the biblical ecclesial teachings and finds from them what features of African are relevant to the Christian theological and anthropological values, and the other one takes the African cultural background as the point of departure. The first section examines the cultural concept of woman as a mother and wife in the African context of the family, focusing mainly on the Bantu and Nilotic tribes of Kenya. This presentation examines African creation myths, oral stories, some key concepts, namely life, family, clan and community, marriage and procreation, and considers the understandings of African theologians and bishops relating to the “the Church as Family.” The second section examines the theological anthropology of John Paul II focusing mainly on his Theology of the Body and Mulieris Dignitatem. -

March 27, 2018

March 27, 2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ================ Nation Media Group’s statement on withdrawal by columnists Nation Media Group notes with regret the position taken by columnists who have been writing for NMG platforms and have decided to stop writing for our publications. We respect their right to take a collective decision, although each of them had an individual contract that we have diligently honoured over the years we have worked with them. We wish to reiterate that overall we have honoured our obligation to respect their views and did not tamper with their positions except to correct basic errors. NMG was founded more than half a century ago on the bedrock of independent voices, diversity and freedom of expression. It is in this regard that we developed, through a process of public participation and published our editorial policy to guide our conduct and journalism. We believe that the principles of independence, fairness and balance, as espoused in our editorial policy, are key to promoting the democratic space whilst being mindful of the impact that information in the public space plays in shaping opinions. We wish to reassure our readers and stakeholders that we continue to be committed to media freedom whilst delivering value in line with their expectations. - Ends - For further details contact: Clifford Machoka Head of Corporate & Regulatory Affairs Email: [email protected] About Nation Media Group Nation Media Group (NMG) was founded by His Highness the Aga Khan in 1959. It was publicly-listed in the Nairobi Stock Exchange since the early 1970s and is the most successful media company in East and Central Africa that currently boasts the largest digital footprint with visitors reaching more than 30 million monthly. -

Climate Change and the Media

THE HEAT IS ON CLIMATE CHanGE anD THE MEDIA PROGRAM INTERNATIONAL ConFerence 3-5 JUNE 2009 INTERNATIONALWorl CONFERENCED CONFERENCE CENTER BONN 21-23 JUNE 2010 WORLD CONFERENCE CENTER BONN 3 WE KEEP THINGS MOving – AND AN EYE ON THE ENVIRONMENT. TABLE OF CONTENTS THAt’s hoW WE GOGREEN. MESSAGE FROM THE ORGANIZERS 4 HOSTS AND SuppORTING ORGANIZATIONS 11 PROTECTING THE ENVIRONMENT 15 GLOBAL STudY ON CLIMATE CHANGE 19 PROGRAM OVERVIEw 22 SITE PLAN 28 PROGRAM: MONDAY, 21 JUNE 2010 33 PROGRAM: TuESDAY, 22 JUNE 2010 82 PROGRAM: WEDNESDAY, 23 JUNE 2010 144 SidE EVENTS 164 GENERAL INFORMATION 172 ALPHABETICAL LIST OF PARTICipANTS 178 For more information go to MAp 192 www.dhl-gogreen.com IMPRINT 193 21–23 JUNE 2010 · BONN, GERMANY GoGreen_Anz_DHL_e_Deutsche Welle_GlobalMediaForum_148x210.indd 1 30.03.2010 12:51:02 Uhr 4 5 MESSAGE FROM THE MESSAGE FROM THE HOST FEDERAL MiNISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS Nothing is currently together more than 50 partners, sponsors, Extreme weather, With its manifold commitment, Germany being debated more media representatives, NGOs, government crop failure, fam- has demonstrated that it is willing to accept than climate change. and inter-government institutions. Co-host ine – the poten- responsibility for climate protection at an It has truly captured of the Deutsche Welle Global Media Forum tially catastrophic international level. Our nation is known for the world’s atten- is the Foundation for International Dialogue consequences that its clean technology and ideas, and for cham- tion. Do we still have of the Sparkasse in Bonn. The convention is climate change will pioning sustainable economic structures that enough time to avoid also supported by Germany’s Federal Foreign have for millions of pursue both economic and ecological aims. -

Section 3: China's Strategic Aims in Africa

SECTION 3: CHINA’S STRATEGIC AIMS IN AFRICA Key Findings • Beijing has long viewed African countries as occupying a cen- tral position in its efforts to increase China’s global influence and revise the international order. Over the last two decades, and especially under General Secretary of the Chinese Com- munist Party (CCP) Xi Jinping’s leadership since 2012, Beijing has launched new initiatives to transform Africa into a testing ground for the export of its governance system of state-led eco- nomic growth under one-party, authoritarian rule. • Beijing uses its influence in Africa to gain preferential access to Africa’s natural resources, open up markets for Chinese exports, and enlist African support for Chinese diplomatic priorities on and beyond the continent. The CCP flexibly tailors its approach to different African countries with the goal of instilling admira- tion and at times emulation of China’s alternative political and governance regime. • China is dependent on Africa for imports of fossil fuels and commodities constituting critical inputs in emerging technology products. Beijing has increased its control of African commodi- ties through strategic direct investment in oil fields, mines, and production facilities, as well as through resource-backed loans that call for in-kind payments of commodities. This control threatens the ability of U.S. companies to access key supplies. • As the top bilateral financier of infrastructure projects across Africa, China plays an important role in addressing the short- age of infrastructure on the continent. China’s financing is opaque and often comes with onerous terms, however, leading to rising concerns of economic exploitation, dependency, and po- litical coercion.