GCAS Syndicate Topic 2003/2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biennial Review 1969/70 Bedford Institute Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Ocean Science Reviews 1969/70 A

(This page Blank in the original) ii Bedford Institute. ii Biennial Review 1969/70 Bedford Institute Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Ocean Science Reviews 1969/70 A Atlantic Oceanographic Laboratory Marine Sciences Branch Department of Energy, Mines and Resources’ B Marine Ecology Laboratory Fisheries Research Board of Canada C *As of June 11, 1971, Department of Environment (see forward), iii (This page Blank in the original) iv Foreword This Biennial Review continues our established practice of issuing a single document to report upon the work of the Bedford Institute as a whole. A new feature introduced in this edition is a section containing four essays: The HUDSON 70 Expedition by C.R. Mann Earth Sciences Studies in Arctic Marine Waters, 1970 by B.R. Pelletier Analysis of Marine Ecosystems by K.H. Mann Operation Oil by C.S. Mason and Wm. L. Ford They serve as an overview of the focal interests of the past two years in contrast to the body of the Review, which is basically a series of individual progress reports. The search for petroleum on the continental shelves of Eastern Canada and Arctic intensified considerably with several drilling rigs and many geophysical exploration teams in the field. To provide a regional depository for the mandatory core samples required from all drilling, the first stage of a core storage and archival laboratory was completed in 1970. This new addition to the Institute is operated by the Resource Administration Division of the Department of Energy, Mines & Resources. In a related move the Geological Survey of Canada undertook to establish at the Institute a new team whose primary function will be the stratigraphic mapping of the continental shelf. -

Antarctic Peninsula

Hucke-Gaete, R, Torres, D. & Vallejos, V. 1997c. Entanglement of Antarctic fur seals, Arctocephalus gazella, by marine debris at Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Islets, Livingston Island, Antarctica: 1998-1997. Serie Científica Instituto Antártico Chileno 47: 123-135. Hucke-Gaete, R., Osman, L.P., Moreno, C.A. & Torres, D. 2004. Examining natural population growth from near extinction: the case of the Antarctic fur seal at the South Shetlands, Antarctica. Polar Biology 27 (5): 304–311 Huckstadt, L., Costa, D. P., McDonald, B. I., Tremblay, Y., Crocker, D. E., Goebel, M. E. & Fedak, M. E. 2006. Habitat Selection and Foraging Behavior of Southern Elephant Seals in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006, abstract #OS33A-1684. INACH (Instituto Antártico Chileno) 2010. Chilean Antarctic Program of Scientific Research 2009-2010. Chilean Antarctic Institute Research Projects Department. Santiago, Chile. Kawaguchi, S., Nicol, S., Taki, K. & Naganobu, M. 2006. Fishing ground selection in the Antarctic krill fishery: Trends in patterns across years, seasons and nations. CCAMLR Science, 13: 117–141. Krause, D. J., Goebel, M. E., Marshall, G. J., & Abernathy, K. (2015). Novel foraging strategies observed in a growing leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) population at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Animal Biotelemetry, 3:24. Krause, D.J., Goebel, M.E., Marshall. G.J. & Abernathy, K. In Press. Summer diving and haul-out behavior of leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) near mesopredator breeding colonies at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Marine Mammal Science.Leppe, M., Fernandoy, F., Palma-Heldt, S. & Moisan, P 2004. Flora mesozoica en los depósitos morrénicos de cabo Shirreff, isla Livingston, Shetland del Sur, Península Antártica, in Actas del 10º Congreso Geológico Chileno. -

Hnitflrcitilc

HNiTflRCiTilC A NEWS BULLETIN published quarterly by the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY (INC) ,m — i * Halley, the British Antarctic Survey's station on the Brunt Ice Shelf, Coats Land,, was rebuilt last season for the third time since 1956-57. This picture taken in March shows one of the four wooden tubes, each of which houses a two-storey building, under construction in a pre-shaped and compacted snow hollow. BAS Copyngh! Registered at Post Office Headquarters, Vol. 10, No. 2 Wellington, New Zealand, as a magazine. SOUTH GEORGIA -.. SOUTH SANDWICH Is «C*2K SOUTH ORKNEY Is x \ 6SignyluK //o Orcadas arg SOUTH AMERICA / /\ ^ Borga T"^00Molodezhnaya \^' 4 south , * /weooEii \ ft SA ' r-\ *r\USSR --A if SHETLAND ,J£ / / ^^Jf ORONMIIDROWNING MAUD LAND' E N D E R B Y \ ] > * \ /' _ "iV**VlX" JN- S VDruzhnaya/General /SfA/ S f Auk/COATS ' " y C O A TBelirano SLd L d l arg L A N D p r \ ' — V&^y D««hjiaya/cenera.1 Beld ANTARCTIC •^W^fCN, uSS- fi?^^ /K\ Mawson \ MAC ROBERTSON LAN0\ \ *usi \ /PENINSULA' ^V^/^CRp^e J ^Vf (set mjp Mow) C^j V^^W^gSobralARG - Davis aust L Siple USA Amundsen-Scon OUEEN MARY LAND flMimy ELLSWORTH , U S A / ^ U S S R ') LAND °Vos1okussR/ r». / f c i i \ \ MARIE BYRO fee Shelf V\ . IAND WILKES LAND Scon ROSS|N2i? SEA jp>r/VICTORIAIj^V .TERRE ,; ' v / I ALAND n n \ \^S/ »ADEUL. n f i i f / / GEORGE V Ld .m^t Dumom d'Urville iranu Leningradskayra V' USSR,.'' \ -------"'•BAlLENYIs^ ANTARCTIC PENINSULA 1 Teniente Matienzo arc 2 Esperanza arg 3 Almirante Brown arg 4 Petrel arg 5 Decepcion arg 6 Vicecomodoro Marambio arg ' ANTARCTICA 7 Ariuro Prat chile 500 1000 Miles 8 Bernardo O'Higgms chile 9 Presidente Frei chile - • 1000 Kilomnre 10 Stonington I. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

2019 Weddell Sea Expedition

Initial Environmental Evaluation SA Agulhas II in sea ice. Image: Johan Viljoen 1 Submitted to the Polar Regions Department, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, as part of an application for a permit / approval under the UK Antarctic Act 1994. Submitted by: Mr. Oliver Plunket Director Maritime Archaeology Consultants Switzerland AG c/o: Maritime Archaeology Consultants Switzerland AG Baarerstrasse 8, Zug, 6300, Switzerland Final version submitted: September 2018 IEE Prepared by: Dr. Neil Gilbert Director Constantia Consulting Ltd. Christchurch New Zealand 2 Table of contents Table of contents ________________________________________________________________ 3 List of Figures ___________________________________________________________________ 6 List of Tables ___________________________________________________________________ 8 Non-Technical Summary __________________________________________________________ 9 1. Introduction _________________________________________________________________ 18 2. Environmental Impact Assessment Process ________________________________________ 20 2.1 International Requirements ________________________________________________________ 20 2.2 National Requirements ____________________________________________________________ 21 2.3 Applicable ATCM Measures and Resolutions __________________________________________ 22 2.3.1 Non-governmental activities and general operations in Antarctica _______________________________ 22 2.3.2 Scientific research in Antarctica __________________________________________________________ -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 78/Tuesday, April 23, 2019/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 78 / Tuesday, April 23, 2019 / Rules and Regulations 16791 U.S.C. 3501 et seq., nor does it require Agricultural commodities, Pesticides SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The any special considerations under and pests, Reporting and recordkeeping Antarctic Conservation Act of 1978, as Executive Order 12898, entitled requirements. amended (‘‘ACA’’) (16 U.S.C. 2401, et ‘‘Federal Actions to Address Dated: April 12, 2019. seq.) implements the Protocol on Environmental Justice in Minority Environmental Protection to the Richard P. Keigwin, Jr., Populations and Low-Income Antarctic Treaty (‘‘the Protocol’’). Populations’’ (59 FR 7629, February 16, Director, Office of Pesticide Programs. Annex V contains provisions for the 1994). Therefore, 40 CFR chapter I is protection of specially designated areas Since tolerances and exemptions that amended as follows: specially managed areas and historic are established on the basis of a petition sites and monuments. Section 2405 of under FFDCA section 408(d), such as PART 180—[AMENDED] title 16 of the ACA directs the Director the tolerance exemption in this action, of the National Science Foundation to ■ do not require the issuance of a 1. The authority citation for part 180 issue such regulations as are necessary proposed rule, the requirements of the continues to read as follows: and appropriate to implement Annex V Regulatory Flexibility Act (5 U.S.C. 601 Authority: 21 U.S.C. 321(q), 346a and 371. to the Protocol. et seq.) do not apply. ■ 2. Add § 180.1365 to subpart D to read The Antarctic Treaty Parties, which This action directly regulates growers, as follows: includes the United States, periodically food processors, food handlers, and food adopt measures to establish, consolidate retailers, not States or tribes. -

Waba Directory 2003

DIAMOND DX CLUB www.ddxc.net WABA DIRECTORY 2003 1 January 2003 DIAMOND DX CLUB WABA DIRECTORY 2003 ARGENTINA LU-01 Alférez de Navió José María Sobral Base (Army)1 Filchner Ice Shelf 81°04 S 40°31 W AN-016 LU-02 Almirante Brown Station (IAA)2 Coughtrey Peninsula, Paradise Harbour, 64°53 S 62°53 W AN-016 Danco Coast, Graham Land (West), Antarctic Peninsula LU-19 Byers Camp (IAA) Byers Peninsula, Livingston Island, South 62°39 S 61°00 W AN-010 Shetland Islands LU-04 Decepción Detachment (Navy)3 Primero de Mayo Bay, Port Foster, 62°59 S 60°43 W AN-010 Deception Island, South Shetland Islands LU-07 Ellsworth Station4 Filchner Ice Shelf 77°38 S 41°08 W AN-016 LU-06 Esperanza Base (Army)5 Seal Point, Hope Bay, Trinity Peninsula 63°24 S 56°59 W AN-016 (Antarctic Peninsula) LU- Francisco de Gurruchaga Refuge (Navy)6 Harmony Cove, Nelson Island, South 62°18 S 59°13 W AN-010 Shetland Islands LU-10 General Manuel Belgrano Base (Army)7 Filchner Ice Shelf 77°46 S 38°11 W AN-016 LU-08 General Manuel Belgrano II Base (Army)8 Bertrab Nunatak, Vahsel Bay, Luitpold 77°52 S 34°37 W AN-016 Coast, Coats Land LU-09 General Manuel Belgrano III Base (Army)9 Berkner Island, Filchner-Ronne Ice 77°34 S 45°59 W AN-014 Shelves LU-11 General San Martín Base (Army)10 Barry Island in Marguerite Bay, along 68°07 S 67°06 W AN-016 Fallières Coast of Graham Land (West), Antarctic Peninsula LU-21 Groussac Refuge (Navy)11 Petermann Island, off Graham Coast of 65°11 S 64°10 W AN-006 Graham Land (West); Antarctic Peninsula LU-05 Melchior Detachment (Navy)12 Isla Observatorio -

Antarctica and Isolate It Geographi- East Falkland

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd S o u t h e r n O c e a n Why Go? Ushuaia............................31 The southern parts of the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans Falkland Islands .............39 form the fifth ocean of the world, the Southern Ocean. Its Stanley ...........................42 wild waters surround Antarctica and isolate it geographi- East Falkland ..................46 cally, biologically and climatically from the rest of the world. Scattered around these waters are the islands that early ex- West Falkland .................48 plorers and sealers encountered before they actually found South Georgia ................50 Terra Australis Incognita. South Orkney Islands .... 59 Visit the rocky but fecund shores of the Falkland Islands South Shetland and South Georgia, with abundant wildlife and history. Islands .............................61 Most cruises from South America call in at the South Shet- Heard & McDonald land Islands or the South Orkney Islands, where people set Islands ............................69 up their first Antarctic outposts. Travelers from Australia, Macquarie Island ........... 70 New Zealand and South Africa approach the continent from New Zealand’s Sub- the Ross Sea side, with seabird-rich Heard and Macquarie Antarctic Islands .............71 islands. Sailing these waters and sighting these windswept isles Best Places to recreates the journeys of early adventurers. Spot Wildlife Top Resources » North coast of South » South Georgia & South Sandwich official site (www. Georgia (p 50 ) sgisland.gs) Loads of info, including permit requirements. » Livingston Island (p 65 ) » South Georgia Heritage Trust (www.sght.org) History/ » West Falkland (p 48 ) wildlife conservation group. » Deception Island (p 65 ) » Falkland Islands (www.falklandislands.com) Central source on the island group. -

National Science Foundation § 670.29

National Science Foundation § 670.29 the unique natural ecological system ASPA 115 Lagotellerie Island, Mar- in that area; and guerite Bay, Graham Land (c) Where a management plan exists, ASPA 116 New College Valley, information demonstrating the consist- Caughley Beach, Cape Bird, Ross Is- ency of the proposed actions with the land management plan. ASPA 117 Avian Island, Marguerite Bay, Antarctic Peninsula § 670.29 Designation of Antarctic Spe- ASPA 118 Summit of Mount Mel- cially Protected Areas, Specially bourne, Victoria Land Managed Areas and Historic Sites ASPA 119 Davis Valley and Forlidas and Monuments. Pond, Dufek Massif, Pensacola Moun- (a) The following areas have been tains designated by the Antarctic Treaty ASPA 120 Pointe-Geologie Parties for special protection and are Archipelego, Terre Adelie hereby designated as Antarctic Spe- ASPA 121 Cape Royds, Ross Island cially Protected Areas (ASPA). The ASPA 122 Arrival Heights, Hut Point Antarctic Conservation Act of 1978, as Peninsula, Ross Island amended, prohibits, unless authorized ASPA 123 Barwick and Balham Val- by a permit, any person from entering leys, Southern Victoria Land or engaging in activities within an ASPA 124 Cape Crozier, Ross Island ASPA. Detailed maps and descriptions ASPA 125 Fildes Peninsula, King of the sites and complete management George Island (25 de Mayo) plans can be obtained from the Na- ASPA 126 Byers Peninsula, Living- tional Science Foundation, Office of ston Island, South Shetland Islands Polar Programs, National Science ASPA 127 Haswell Island Foundation, Room 755, 4201 Wilson ASPA 128 Western shore of Admiralty Boulevard, Arlington, Virginia 22230. Bay, King George Island, South Shet- ASPA 101 Taylor Rookery, Mac. -

Antarctic Reader

ANTARCTICA: THE READER ................................................................ SECTION 1 3 Conserving Antarctica 4 Guidance for Visitors 5 Antarctica’s Historic Heritage SECTION 4 45 The Antarctic Treaty SECTION 2 9 Places You May Visit SECTION 5 9 Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) 49 The Physical Environment 11 South Georgia 49 The Southern Ocean 13 South Sandwich Islands 51 Antarctica 14 South Orkney Islands 53 Geology 14 Weddell Sea 54 Climate 16 South Shetland Islands 56 The Antarctic Circle 17 Antarctic Peninsula 57 Icebergs, Glaciers and Sea Ice 20 The Historic Ross Sea Sector 60 The Ozone Hole 24 New Zealand’s Subantarctic Islands 62 Global Warming SECTION 3 SECTION 6 29 Explorers and Scientists 65 The Biological Environment 29 Terra Australis Exploration 66 Life in Antarctica 30 The Age of Sealers (1780-1892) 67 Adapting to the Cold 34 The Heroic Age & Continental Penetration 70 The Kingdom of Krill 38 Mechanical Age and Whaling Period 72 The Wildlife 41 Permanent Stations 72 Antarctic Squids 42 Pax Antarctica: The Treaty Period 73 Antarctic Fishes 74 Antarctic Birds 83 Antarctic Seals 88 Antarctic Whales SECTION 7 97 Wildlife Checklist TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORIC HUT ........................................................... The first humans to spend a winter in Antarctica erected this hut in February 1899. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on Earth, a place that we believe must be preserved in its present pristine state. Many governments and non-governmental organizations and all the leading companies arranging expeditions to the region are working together to ensure that Antarctica’s spectacular scenery, unique wildlife and extraordinary wilderness will be protected for future generations to enjoy. -

World Climate Research Programme

WORLD CLIMATE RESEARCH PROGRAMME PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CLIVAR CONFERENCE (Paris, France, 2-4 December 1998) WCRP-109 WMO/TD No.954 ICPO No. 27 June 1999 ICSU WMO UNESCO The World Climate Programme launched by the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) includes four components: The World Climate Data and Monitoring Programme The World Climate Applications and Services Programme The World Climate Impact Assessment and Response Strategies Programme The World Climate Research Programme The World Climate Research Programme is jointly sponsored by the WMO, the International Council of Scientific Unions and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO. NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organisation concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CLIVAR CONFERENCE (Paris, France, 2-4 December 1998) WCRP-109 WMO/TD No.954 ICPO No. 27 June 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Preface by co-Chairs, Scientific Steering Group iii Foreword by Chairman, Conference Organising Committee 1 Conference Programme 3 Conference Statement 5 Opening Statement by Professor G.O.P. Obasi, Secretary General, WMO 7 Welcome Address by Patricio A. Bernal, Assistant Director General, UNESCO 9 SCIENTIFIC PRESENTATIONS Global environmental change and the need for international research programmes Dr. Bert Bolin, Sweden 11 Conference structure and objectives Dr. Allyn Clarke, CLIVAR SSG Co-Chair 15 The evolution of the CLIVAR Science Dr. -

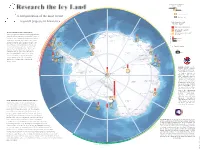

A Categorization of the Most Recent Research Projects in Antarctica

Percentage of seasonal population at the research station 25% 75% N o r w a y C Population in summer l a A categorization of the most recent i m Population in winter research projects in Antarctica Goals of research projects (based on describtion of NSF U.S. Antarctic Program) Projects that are trying to understand the region and its ecosystem Orcadas Station (Argentina) Projects that using the region as a platform to study the upper space i m Signy Station (UK) a and atomosphere l lf Fimbul Ice She Projects that are uncovering the regions’ BASIS OF THE CATEGORIZATION C La SANAE IV Station P r zar effect and repsonse to global processes i n ev a (South Africa) c e Ice such as climate This map categorizes the most recent research projects into three s s Sh n A s t elf i King Sejong Station r i d t (South Korea) Troll Station groups based on the goals of the projects. The three categories tha Syowa Station n Mar (Norway) Pr incess inc (Japan) e Pr ess 14 projects are: projects that are developed to understand the Antarctic g Rag nhi r d e ld Molodezhnaya n c a I Isl Station (Russia) 2 projects A lle n region and its ecosystems, projects that use the region as a oinvi e DRONNING MAUD J s R 3 projects r i a is n L er_Larse G Marambio Station - er R s platform to study the upper atmosphere and space, and (Argentina) ii A R H ENDERBY projects that are uncovering Antarctica’s effects on (and A d Number of research projects M n Mizuho Station sla Halley Station er I i Research stations L ss (Norway) p mes Ro (UK) Na responses to) global processes such as climate.