Critical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inspire Antarctica Expedition (Iae) 2011 March 3-18, 2011

INSPIRE ANTARCTICA EXPEDITION (IAE) 2011 MARCH 3-18, 2011 RECYCLING COUNCIL OF ALBERTA OCTOBER 7, 2011 PRESENTED BY: GAVIN SCOTT & TYLER BARKHOUSE Who is Robert Swan and why the heck did we go all the way to Antarctica to meet him?? WHAT IS 2041? • Organization created by Robert Swan, OBE • Global mission to help reduce environmental damage through global and local initiatives The Mission of 2041 is to: TO CHALLENGE INDUSTRY & BUSINESS TO USE CLEANER ENERGY AND INSPIRE CHAMPIONS WITHIN ORGANISATIONS TO CARRY THE MESSAGE FORWARDS Linking Leadership with Sustainability Signatories on the Antarctic Treaty GLOBAL MISSION ACCOMPLISHED 1500 TONS OF SOLID WASTE REMOVED JAN 2002 10 Things Most People (Including Us) Didn’t Know About Antarctica: 1. It’s a CONTINENT – not a country (ok we knew that) 2. It is 1.7 times the size of Australia 3. It contains 90% of the world ice…. 4. … and 70% of the world’s freshwater 5. 180 million years ago, Antarctica was attached to South America… and was tropical! 10 Things Most People (Including Us) Didn’t Know about Antarctica: 6. Three major oceans, (Atlantic, Indian and Pacific) merge in a 40 km strip on the outer edge of Antarctica 7. If all of the ice in Antarctica melted, sea levels would rise between 50 and 60 m. 8. Antarctica is the coldest, windiest, and driest place on earth . In some places like the Dry Valleys, it has not rained for thousands of years. 10 Things Most People (Including Us) Didn’t Know about Antarctica: 9. The ozone hole above Antarctica covers 27 million km2. -

British Team to Head to Antarctica to Complete Captain Scott's Terra

STRICTLY UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL WED 5 JUNE, 2013, 11.00 (GMT – London) MEDIA RELEASE, 5 June 2013 British Team To Head to Antarctica to Complete Captain Scott’s Terra Nova Expedition • Two Brits to honour the legacy of iconic British explorer, Captain Robert Falcon Scott by setting out to complete his ill-fated Terra Nova expedition for the first time, more than 100 years after it was first attempted. • The Scott Expedition will be the longest unsupported polar journey in history and a landmark expedition in terms of technical innovation • The expedition will depart in October 2013 On the eve of Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s birthday, two British polar explorers Ben Saunders and Tarka L’Herpiniere, in partnership with Intel and Land Rover today announced their intention to depart in October 2013 to complete Scott’s ill-fated 1910-1912 Terra Nova expedition – an unsupported return journey from the edge of Antarctica to the South Pole. Historically significant, it will be the first time in more than 100 years that Scott’s journey has been attempted and is being undertaken under the patronage of Scott’s grandson, Falcon Scott. At 1,800 miles (equivalent to 69 back-to-back marathons) it will be the longest unsupported polar journey in history and set a new benchmark in terms of expedition technology. Ben and Tarka will use new 4th Generation Intel® Core™ Processor technology to upload videos, photos, blogs and key data in near real-time as the trip progresses. The expedition will also have its own YouTube channel (www.youtube.com/scottexpedition). -

The Antarctican Society 905 North Jacksonville Street Arlington, Virginia 22205 Honorary President — Ambassador Paul C

THE ANTARCTICAN SOCIETY 905 NORTH JACKSONVILLE STREET ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA 22205 HONORARY PRESIDENT — AMBASSADOR PAUL C. DANIELS ________________________________________________________________ Presidents: Vol. 85-86 November No. 2 Dr. Carl R. Eklund, 1959-61 Dr. Paul A. Siple, 1961-2 Mr. Gordon D. Cartwright, 1962-3 RADM David M. Tyree (Ret.) 1963-4 Mr. George R. Toney, 1964-5 A PRE-THANKSGIVING TREAT Mr. Morton J. Rubin, 1965-6 Dr. Albert P. Crary, 1966-8 Dr. Henry M. Dater, 1968-70 Mr. George A. Doumani, 1970-1 MODERN ICEBREAKER OPERATIONS Dr. William J. L. Sladen, 1971-3 Mr. Peter F. Bermel, 1973-5 by Dr. Kenneth J. Bertrand, 1975-7 Mrs. Paul A. Siple, 1977-8 Dr. Paul C. Dalrymple, 1978-80 Commander Lawson W. Brigham Dr. Meredith F. Burrill, 1980-82 United States Coast Guard Dr. Mort D. Turner, 1982-84 Dr. Edward P. Todd, 1984-86 Liaison Officer to Chief of Naval Operations Washington, D.C. Honorary Members: Ambassador Paul C. Daniels on Dr. Laurence McKiniey Gould Count Emilio Pucci Tuesday evening, November 26, 1985 Sir Charles S. Wright Mr. Hugh Blackwell Evans 8 PM Dr. Henry M. Dater Mr. August Howard National Science Foundation Memorial Lecturers: 18th and G Streets NW Dr. William J. L. Sladen, 1964 RADM David M. Tyree (Ret.), 1965 Room 543 Dr. Roger Tory Peterson, 1966 Dr. J. Campbell Craddock, 1967 Mr. James Pranke, 1968 - Light Refreshments - Dr. Henry M. Dater, 1970 Sir Peter M. Scott, 1971 Dr. Frank T. Davies, 1972 Mr. Scott McVay, 1973 Mr. Joseph O. Fletcher, 1974 Mr. Herman R. Friis, 1975 This presentation by one of this country's foremost experts on ice- Dr. -

Operational Meteorology Program, Deep Freeze 81

a r \ )! 9 i ji ii! _-4 - -• - - -.---$ -: Figure 2. USNS Maumee moored at the McMurdo ice wharf dis- charging fuel. (U.S. Navy photo) Figure 3. USNS Southern Cross, on her voyage, arriving at the Zealand. Southern Cross arrived at Port Lyttelton on 18 January, McMurdo ice wharf. (U.S. Navy photo) discharged and loaded cargo, and departed on 21 January (see figure 3). Polar Star escorted Southern Cross into Winter Quar- ters Bay on 27 January, and offloading and retrograde loading nel embarked. The ship sailed for New Zealand on 16 Febru- was accomplished by 1 February. On 7 February Southern Cross ary. M/V World Discoverer (Singapore) moored at the ice wharf arrived Port Lyttelton, and on 10 February departed for Port on 11 February and discharged passengers for tours of Hueneme, California, where she arrived on 23 February. McMurdo and Scott Base. World Discoverer sailed for Capes Three other ships called at McMurdo Station during the Royds and Evans on the 12th to visit the historic huts and 1980-81 season. RJV Benjamin Bowring (United Kingdom), the rookeries and returned to McMurdo during the afternoon to Transglobe Expedition ship under charter to the New Zealand drop off "guides" prior to departing for Port Lyttelton, New Zealand. M/V Lindblad Explorer (Panama) arrived 18 February Department of Science and Industrial Research (osm), operated and departed on the 19th. Navy personnel conducted tours of in the Ross Sea and McMurdo Sound areas. The Bowring moored at the ice wharf on 20 January to offload Transglobe the local area. -

Who Is Sir Ranulph Fiennes?

Who Is Sir Ranulph Fiennes? Sir Ranulph Fiennes is a British expedition leader who has broken world records, won many awards and completed expeditions on a range of different modes of transport. These include hovercraft, riverboat, manhaul sledge, snowmobile, skis and a four-wheel drive vehicle. He is also the only living person who has travelled around the Earth’s circumpolar surface. Did You Know…? Circumpolar means Sir Ranulph does not call himself to go around the an explorer as he says he has only Earth’s North Pole once mapped an unknown area. and South Pole. The Beginning of an Expedition Leader Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes was born on 7th March 1944 in Windsor, UK. His father was killed during the Second World War and after the war, Ranulph’s mother moved the family to South Africa. He lived there until he was 12 years old. He returned to the UK where he continued his education, later attending Eton College. Ranulph joined the British army, where he served for eight years in the same regiment that his father had served in, the Royal Scots Greys. While in the army, Ranulph taught soldiers how to ski and canoe. After leaving the army, Ranulph and his wife decided to earn money by leading expeditions. A World of Expeditions North Pole Arctic Mount Everest The Eiger The River Nile South Pole Antarctic The Transglobe Expedition In 1979, Ranulph, his wife Ginny and friends Charles Burton and Oliver Shepherd embarked on an expedition to the Antarctic which was planned by Ginny, an explorer in her own right. -

Flnitflrclid

flNiTflRClID A NEWS BULLETIN published quarterly by the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY (INC) A New Zealand geochemist, Dr W. F. Giggenbach, descends into the inner crater of Mt Erebus on December 23 last year in an unsuccessful attempt to take gas samples. Behind him in the lava lake of the volcano where the temperature is 1000deg Celsius. On his rucksack he carries titanium gas sampling rods. Photo by Colin Monteath VOl. 8, NO. 1 1 . Wellington, New Zealand, as a magazine. o6pt61*11061% I 979I ' . SOUTH SANDWICH Is SOUTH GEORGIA f S O U T H O R K N E Y I s x \ *#****t ■ /o Orcadas arg \ - aanae s» Novolazarevskaya ussr XJ FALKLAND Is /*Signyl.uK ,,'\ V\60-W / -'' \ Syowa japan SOUTH AMERICA /'' /^ y Borga 7 s a "Molodezhnaya A SOUTH , .a /WEDDELL T\USSR SHETLAND DRONNING MAUD LAND ENOERBY \] / Halley Bay^ ununn n mMUU / I s 'SEA uk'v? COATS Ld LAND JJ Druzhnaya ^General Belgrano arg ANTARCTIC %V USSR *» -» /\ ^ Mawson MAC ROBERTSON LANO\ '■ aust /PENINSULA,' "*■ (see map below) /Sohral arg _ ■ = Davis aust /_Siple — USA Amundsen-Scott / queen MARY LAND gMirny [ELLSWORTH u s a / ; t h u s s i " LANO K / ° V o s t o k u s s r / k . MARIE BYRD > LAND WILKES LAND Scott kOSS|nzk SEA I ,*$V /VICTORIA TERRE ' •|Py»/ LAND AOEilE ,y Leningradskaya X' USSR,''' \ 1 3 -------"';BALLENYIs ANTARCTIC PENINSULA ^ v . : 1 Teniente Matienzo arg 2 Esperanza arc 3 Almirante Brown arg 4 Petrel arg 5 Decepcion arg 6 Vicecomodoro Marambio arg ' ANTARCTICA 7 Arturo Prat chile 8 Bernardo O'Higgins chile 1000 Miles 9 Presidents Frei chile * ? 500 1000 Kilometres 10 Stonington I. -

HN.Tflrcitiici

HN.TflRCiTiICi A NEWS BULLETIN published quarterly by the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY (INC) 4 !*y/. A New Zealand/West German/American geological field party in Northern Victoria Land unloads equipment from a United States Navy ski-equipped Hercules at Crosscut Peak in the Millen Range. Antarctic Division photo \/nl»«• ■ 1ftIU, blf\I1U. ftO RegisteredWellington, Newat PostZealand, Office as Headquarters,a magazine. UCV/CII nfiromhor lUCI , 1 I Qfl/1oOH SOUTH GEORGIA SOUTH SANDWICH li' / S O U T H O R K N E Y I s ' \ e#2?KS /o Orcadas arg v rt FALKLAND Ij /6SignyluK y SajiMsA^^^qyoUiarevilaya > K 6 0 " W / SOUTH AMERICA * /' ,\ {/ Boiga / nJ^L^T. \w\ 4 s o u t h , * / w e d d e l l \ 3 S A / % T ^ & * ^ V SHETLAND J J!*, ,' / Hallev Bavof DRONNING MAUD LANO ENDERBY ^ / , s A V V ' ' / S E A u k T J C O A T S L d I / L A N D , , - Druzhnaya ^General Belgrano arg u s s r , < 6 V > ^ - " ^ ~ ^ I / K \ M a w s o n ANTARCTIC -tSS^ MAC ROBERTSON LAND\ '. *usi /PENINSULA'^ (sn map belowl ' 'Sobral arg Davis ausi L Siple. USA Amundsen-Scon OUEEN MARY LAND <!MimY ELLSWORTH i , J j U S S R LAND /x. ' / vostok° Vo s t o kussr/ u s s r / rrv > . MARIE BYRD Ice Shelf V>^ \^ / * L LAND \ W I L K E S L A N D ^ - / ' Rossr?#Vanda?' / y^\/ SEA IV^r/VICTORIA .TERRE A 7 ■ 4F&/ LMO \/ kOtU^y/ Ax ( G E O R G E V \ A . -

ANTARCTIC BOOKS—A READING LIST the AAD Library at Kingston Has a Comprehensive Collection of Polar Material

ANTARCTIC BOOKS—A READING LIST The AAD Library at Kingston has a comprehensive collection of polar material. The books listed below have been selected for general interest. They are available in the library and should also be available in the larger Australian libraries. Most are available in the station libraries. Douglas Mawson, the Survivor, by David Parer and Elizabeth Parer-Cook (Morwell, Victoria: Allela Books and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 1983). Antarctic Odyssey, by Phillip Law (Melbourne: Heinemann, 1983). Antarctic Resources Policy: Scientific, Legal and Political Issues, edited by Francisco Orrego Vicuna (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983). Antarctic Days with Mawson: A Personal Account of the British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition of 1929-31, by Harold Fletcher (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1984). Antarctic Ecology, edited by R M Laws (London: Academic Press, 1984). Australia's Antarctic Policy Options, edited by Stuart Harris (Canberra: Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies, Australian National University, 1984 - CRES Monograph 11). Antarctica: Great Stories from the Frozen Continent (Sydney: Reader's Digest, 1985). Antarctica: Our Last Great Wilderness, by Geoff Mosley (Hawthorn, Victoria Australian Conservation Foundation, 1986. Women on the Ice: A History of Women in the Far South, by Elizabeth Chipman (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1986). Going to Extremes: Project Blizzard and Australia's Antarctic Heritage by (Sydney: Doubleday, 1986). International Law and Australian Sovereignty in Antarctica, by Gillian Triggs (Sydney: Legal Books Pty Ltd, 1986). In the Footsteps of Scott, by Roger Mear and Robert Swan (London: Jonathan Cape, 1987). Antarctic Science, edited by DWH Walton, with contributions by CSM Doake, JR Dudley, I Everson and RM Laws (Cambridge; Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1987). -

Flnitflrcililcl

flNiTflRCililCl A NEWS BULLETIN published quarterly by the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY (INC) svs-r^s* ■jffim Nine noses pointing home. A team of New Zealand huskies on the way back to Scott Base after a run on the sea ice of McMurdo Sound. Black Island is in the background. Pholo by Colin Monteath \f**lVOL Oy, KUNO. O OHegisierea Wellington, atNew kosi Zealand, uttice asHeadquarters, a magazine. n-.._.u—December, -*r\n*1981 SOUTH GEORGIA SOUTH SANDWICH Is- / SOUTH ORKNEY Is £ \ ^c-c--- /o Orcadas arg \ XJ FALKLAND Is /«Signy I.uk > SOUTH AMERICA / /A #Borga ) S y o w a j a p a n \ £\ ^> Molodezhnaya 4 S O U T H Q . f t / ' W E D D E L L \ f * * / ts\ xr\ussR & SHETLAND>.Ra / / lj/ n,. a nn\J c y DDRONNING d y ^ j MAUD LAND E N D E R B Y \ ) y ^ / Is J C^x. ' S/ E A /CCA« « • * C",.,/? O AT S LrriATCN d I / LAND TV^ ANTARCTIC \V DrushsnRY,a«feneral Be|!rano ARG y\\ Mawson MAC ROBERTSON LAND\ \ aust /PENINSULA'5^ *^Rcjnne J <S\ (see map below) VliAr^PSobral arg \ ^ \ V D a v i s a u s t . 3_ Siple _ South Pole • | U SA l V M I IAmundsen-Scott I U I I U i L ' l I QUEEN MARY LAND ^Mir"Y {ViELLSWORTHTTH \ -^ USA / j ,pt USSR. ND \ *, \ Vfrs'L LAND *; / °VoStOk USSR./ ft' /"^/ A\ /■■"j■ - D:':-V ^%. J ^ , MARIE BYRD\Jx^:/ce She/f-V^ WILKES LAND ,-TERRE , LAND \y ADELIE ,'J GEORGE VLrJ --Dumont d'Urville france Leningradskaya USSR ,- 'BALLENY Is ANTARCTIC PENIMSULA 1 Teniente Matienzo arg 2 Esperanza arg 3 Almirante Brown arg 4 Petrel arg 5 Deception arg 6 Vicecomodoro Marambio arg ' ANTARCTICA 7 Arturo Prat chile 8 Bernardo O'Higgins chile 9 P r e s i d e n t e F r e i c h i l e : O 5 0 0 1 0 0 0 K i l o m e t r e s 10 Stonington I. -

Biographical Records

Usage Comments Term list controlled? Repeatable? ObjectIdentity Number Expedition name in standard format (matches term list) *Mandatory field Yes: "expedition-names". *In format 'Official name YYYY-YY (Ship)', e.g. 'British National Antarctic Expedition 1901-04 (Discovery)' Administration ItemCategory Type "expedition" Progress Type "BIO" Keyword Whether image/record is to be suppressed on the web, e.g. "P" or "R" *P = picture suppressed on the web Yes: "SPRI WebRecordRepression" (termlist) - leave blank if not to be repressed *R = record suppressed on the web Content Event Type "Arctic expedition" or "Antarctic expedition" *Repeat if necessary (i.e. Transglobe expedition is Arctic and Yes: If an expedition is both Arctic and Antarctic Antarctic) *Focus on polar events/associations - expeditions, involvement in SPRI, Antarctic Treaty EventName Expedition name in standard format (matches term list) *In format 'Official name YYYY-YY (Ship)', e.g. 'British National Yes: Controlled by the 'ObjectIdentity/Number' - must be the same Antarctic Expedition 1901-04 (Discovery)' Date DateBegin Expedition start date (year only) *Expedition start date from expedition name, in format YYYY DateEnd Expedition start date (year only) *Expedition end date from expedition name, in format YYYY Note Place PlaceName Location of expedition *Free text field *N.B. Not been used much yet - just fill in to broad level Continent Location of expedition *Free text field SummaryText *Free text field *Overarching description of the expedition - aims, events and achievements, -

Until Covid-19, Isolation For

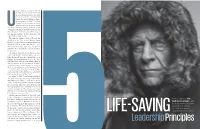

ntil covid-19, isolation for sir Ranulph Fiennes meant the 90 days he spent floating around in the Arctic Ocean on an ice floe in minus 20°C during the 160,000 kilometer Trans- globe Expedition (1979–82). Food had virtually run out and every so often a U half-ton polar bear, the world’s deadli- est predator with sharp claws, big teeth and capable of running at 60km/h, would climb onto his icy raft. The only means of defending himself was banging two saucepans together. “It drove them nuts. And they usually ran away,” he says. The man the Guinness Book of Records has described as the “The World’s Greatest Living Explorer” says his solution to mental isolation, then and in the current global lockdown, is to “keep telling yourself to stay patient. Stay cheerful. And remember there are millions of people elsewhere far worse off.” The trial of Anne Boleyn, The Battle of Agin- court, Lady Godiva, Finsbury Square and actor Ralph Fiennes all have direct family links to Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes, Bt., DSO, OBE (aka “Ran”). He is an extraordinary character and a good friend. We meet in Dubai at the much- acclaimed Emirates Airline Festival of Literature where he is promoting his 25th book—his autobi- ography Mad, Bad and Dangerous To Know. That was how the father of his childhood sweetheart and first wife, Ginny, described him. Is he? He admits to “Bad” from having misbehaved and spent time in various prisons, “but the Mad and Dangerous to Know … well, they’re up for debate,” he says. -

23 English Pages

Vol 23, May 2007 NEWSLETTER FOR THE Canadian Antarctic Research Network BOOMERANG: Exploring the Universe from the Antarctic Sky Carrie MacTavish Inside In January of 2003, the BOOMERANG telescope completed a second successful Antarctic mission, probing the oldest light in the Universe, addressing the most BOOMERANG: fundamental of cosmological questions and testing the parameters of Big Bang Exploring the Universe Theory. The BOOMERANG group is an international collaboration of 35 scientists from the Antarctic Sky 1 from Canada, Italy, the United States and the U.K. The Canadian contingent is from the University of Toronto (Departments of Physics and Astronomy) and First Light for the the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics. The latter played the lead South Pole Telescope 5 role in data analysis, while the former took the lead on the telescope motion control and pointing instrumentation. Part of the team is shown in Figure 1. The First Research Cruise to Study Adaptations and Evolution results from this mission were published in 2006 (Jones and others, 2006; Mac- of Fauna after the Collapse of Tavish and others, 2006; Masi and others, 2006; Montroy and others, 2006; Pia- the Larsen A and B Ice Shelves 8 centini and others, 2006). BOOMERANG is a balloon-borne, microwave telescope designed to measure Restoration of Shackleton’s the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). The CMB is one of the firm predictions Nimrod Hut at Cape Royds 12 of Big Bang theory and is a field of electromagnetic radiation that is cosmic in origin, that is originating from the Universe itself. It radiates in the microwave News in Brief 13 (0.3–630 GHz), with a near perfect black-body spectrum which peaks at 160.4 GHz, corresponding to a temperature of 2.725 K.