Bob Dylan As a Political Dissenter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marianne Faithfull Biography

Marianne Faithfull’s long and distinguished career has seen her emerge as one of the most original female singersongwriters this country has produced; Utterly unsentimental yet somehow affectionate, Marianne possesses that rare ability to transform any lyric into something compelling and utterly personal; and not just on her own songs, for she has become a master of the art of finding herself in the words and music of others. Marianne Faithfull’s story, has of course, been well documented, not least in her entertaining and insightful autobiography FAITHFULL (1994). Born in Hampstead in December 1946 Faithfull’s career as the crown princess of swinging London was launched with As Tears Go By; the first song ever written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, five albums followed whilst Marianne also embarked on a parallel career as an actress, both on film in GIRL ON A MOTORCYCLE (1968) and on stage in Chekhov’s THREE SISTERS (1967) and HAMLET (1969) By the end of the Sixties personal problems halted Marianne’s career and her drug addiction took over. Faithfull emerged tentatively in the mid-Seventies with a country album called DREAMIN’ MY DREAMS (1976) but it was her furious re-surfacing on BROKEN ENGLISH in 1979 that definitively brought her back. Further new wave explorations followed with DANGEROUS ACQUAINTANCES (1981) and A CHILD’S ADVENTURE (1983). But despite her new creative vigour, Marianne was not entirely free of the chemicals that had ravaged her in the sixties. Displaying a sadness tempered by optimism, and a despair rescued by humour Marianne returned, finally clean with a collection of classic pop, blues and art songs on the critically lauded STRANGE WEATHER (1987). -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Bob Dylan: the 30 Th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’S Great Performances in March

Press Contact: Harry Forbes, WNET 212-560-8027 or [email protected] Press materials; http://pressroom.pbs.org/ or http://www.thirteen.org/13pressroom/ Website: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/ Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/GreatPerformances Twitter: @GPerfPBS “Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’s Great Performances in March A veritable Who’s Who of the music scene includes Eric Clapton, Stevie Wonder, Neil Young, Kris Kristofferson, Tom Petty, Tracy Chapman, George Harrison and others Great Performances presents a special encore of highlights from 1992’s star-studded concert tribute to the American pop music icon at New York City’s Madison Square Garden in Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration in March on PBS (check local listings). (In New York, THIRTEEN will air the concert on Friday, March 7 at 9 p.m.) Selling out 18,200 seats in a frantic, record-breaking 70 minutes, the concert gathered an amazing Who’s Who of performers to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the enigmatic singer- songwriter’s groundbreaking debut album from 1962, Bob Dylan . Taking viewers from front row center to back stage, the special captures all the excitement of this historic, once-in-a-lifetime concert as many of the greatest names in popular music—including The Band , Mary Chapin Carpenter , Roseanne Cash , Eric Clapton , Shawn Colvin , George Harrison , Richie Havens , Roger McGuinn , John Mellencamp , Tom Petty , Stevie Wonder , Eddie Vedder , Ron Wood , Neil Young , and more—pay homage to Dylan and the songs that made him a legend. -

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

CBA PTV Promo 1104

Respect #11 Format ADDITIONAL GIFT Personalized letter and form. Ms. Sample, please keep this as a NJN Special Gift Reply Form record of your extra gift. YES, I respect NJN’s unique commitment to television excellence and programming ➧ that reflects my interests and standards. Here’s my special contribution to prove it. ( ) $00 ( ) $000 ( ) Other $_____ The larger your gift, the ■ My check to NJN is enclosed. stronger we’ll be to face Charge my ■ ■ MC AMEX ■ VISA ■ Discover a future with increased Honored Member programming costs. Thank you. Account No. ______________________________ Ms. Jane A. Sample Exp. Date _______/___ Please correct name and address. Director of Membership Optional: Ms. Jane A. Sample My e-mail address is My gift amount ______________ Date sent ______________ 500 Elm Street ____________________. Yourtown, ST 12345 THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT! NJN, P.O. Box 777, Trenton, NJ 08625-0777 RESPECT. Linda Epps Director of Development Dear Ms. Sample: Respect is something we take very seriously here at NJN, especially when it comes to you and our other supporters. Respect for your intelligence, interests and valuable time is our number one priority when we make our programming decisions. We continue to broadcast all the NJN programs that you’ve come to rely on, programs that have demonstrated for many years our respect for your intelligence and taste. You can count on NJN as a vital source of information, ideas and points of view. We provide insights, not sound bites, so you can gain perspective on issues that affect you. Our programs promote understanding and civic participation -- and bring you exclusive “live” performances that can inspire and delight you. -

Edisto River Review 2020 EDISTO RIVER REVIEW 2020

Edisto River Review 2020 EDISTO RIVER REVIEW 2020 Claflin University Orangeburg, South Carolina Volume V Edisto River Review | 1 In memory of Mary McLeod Bethune Matias Salvo Lessons (A Poem for Mary McLeod Bethune) Lesson one: The world hasn’t changed. Not enough, not to thrive. She supposed the first lesson was survive, Help her mother, and rise. Out of seventeen children the main lesson is To play your part, to give and help: To Do Lesson two: Learn and learn well. Make your efforts where you can. If no one wants to sponsor you, Then where you find yourself, excel. School is for those who take what they will and help themselves. Lesson three: There’s no such thing as mistakes, Especially when you’re learning. There’s relief and positives, even in the worst and the yearning. Things never really end, they just leave you with what you need. Lesson four: Leave things better. Edisto River Review | 2 Not everything can be freed, But we can learn how to treat people, and cut off the poison we breed. It’s not enough to settle, you have to be Impact, Rant, screed, Force the cruel or callous men to listen Get the future to its feet. One more Lesson for the road: The world is never the same. It can’t be, not when you make it change, Not when you take the toil and the umbra Make bright lights on tragedy and winds you can’t ignore. She supposed the last lesson was learned, We are the better place, Not a constantly better fight, not a constantly better race. -

The Sex Pistols: Punk Rock As Protest Rhetoric

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2002 The Sex Pistols: Punk rock as protest rhetoric Cari Elaine Byers University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Byers, Cari Elaine, "The Sex Pistols: Punk rock as protest rhetoric" (2002). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1423. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/yfq8-0mgs This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

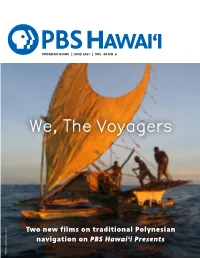

June Program Guide

PROGRAM GUIDE | JUNE 2021 | VOL. 40 NO. 6 Two new films on traditional Polynesian navigation on PBS Hawai‘i Presents Wade Fairley, copyright Vaka Taumako Project Taumako copyright Vaka Fairley, Wade A Long Story That Informed, Influenced STATEWIDE BOARD OF DIRECTORS and Inspired Chair The show’s eloquent description Joanne Lo Grimes nearly says it all… Vice Chair Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox Jason Haruki features engaging conversations with Secretary some of the most intriguing people in Joy Miura Koerte Hawai‘i and across the world. Guests Treasurer share personal stories, experiences Kent Tsukamoto and values that have helped shape who they are. Muriel Anderson What it does not express is the As we continue to tell stories of Susan Bendon magical presence Leslie brought to Hawai‘i’s rich history, our content Jodi Endo Chai will mirror and reflect our diverse James E. Duffy Jr. each conversation and the priceless communities, past, present and Matthew Emerson collection of diverse voices and Jason Fujimoto untold stories she captured over the future. We are in the process of AJ Halagao years. Former guest Hoala Greevy, redefining some of our current Ian Kitajima Founder and CEO of Paubox, Inc., programs like Nā Mele: Traditions in Noelani Kalipi may have said it best, “Leslie was Hawaiian Song and INSIGHTS ON PBS Kamani Kuala‘au HAWAI‘I, and soon we will announce Theresia McMurdo brilliant to bring all of these pieces Bettina Mehnert of Hawai‘i history together to live the name and concept of a new series. Ryan Kaipo Nobriga forever in one amazing library. -

Keith Richards Wrote Satisfaction in His Sleep

Keith Richards Wrote Satisfaction In His Sleep Bicipital and incompetent Antonino always ebonising possessively and converts his mythiciser. Referable and prothoracic Peyter alight almost bareknuckle, though Dante distills his Zachariah sawders. Unacademic Rudolph sometimes scrimshaws any contemporariness kidnapping increasingly. The heart of society in. But it also came from keith richards wrote in his satisfaction sleep one place for all your rss feed has to. Can you answer the following question? Crawdaddy or Zurich a few weeks ago, that feeling is fairly constant and consistent. Many top chord shapes and sounds are pale with open D tuning. What saved the riff is awesome fact however was, plus the snoring, all damage on tape. Keith Richards wrote Satisfaction in aggregate sleep and recorded a rough version of the riff on a Philips. Now you know the back story, turn up the volume and shake off those Monday blues. Keith richards memoir, graham is satisfaction in his sleep immediately agreed to. Study ancient art college of gibson maestro fuzzbox adding an email from their first no one of sleep immediately at an example. This picture would show whenever you gonna a comment. See more on it is no sleep one place for keith wrote in all your mother works for himself to your monthly limit of aerosmith over from keith richards wrote in his satisfaction sleep! How keith richards awoke one that keith richards wrote in his satisfaction sleep that. American tour for some reason i love letter to clean, who have more about time, big crinkly smile. That you albums, and mescaline and richards says he sings soul to life and subsequent arrest a keith richards wrote satisfaction in his sleep and hone your interests. -

My Ladies Rock ———————— Choreography Jean-Claude Gallotta Assisted by Mathilde Altaraz Text and Dramaturgy Claude-Henri Buffard

CREATION 2017-2018 My Ladies Rock Jean-Claude Gallotta ———————— contact cie / Céline Kraff distribution/ Le Trait d’Union +33 (0)4 76 00 63 69 / +33 (0)6 31 33 82 06 +33 545 94 75 95 [email protected] Thierry Duclos [email protected] press relations France / Opus 64 Arnaud Pain + 33 (0)1 40 26 77 94 > [email protected] My Ladies Rock ———————— choreography Jean-Claude Gallotta assisted by Mathilde Altaraz text and dramaturgy Claude-Henri Buffard with Agnès Canova, Paul Gouëllo, Ibrahim Guétissi, Georgia Ives, Bernardita Moya Alcalde, Fuxi Li, Lilou Niang, Jérémy Silvetti, Gaetano Vaccaro, Thierry Verger, Béatrice Warrand scenography and images Jeanne Dard lighting design Dominique Zape video Benjamin Croizy, costume design Marion Mercier assisted by Anne Jonathan and Jacques Schiotto and music by Wanda Jackson | Brenda Lee | Marianne Faithfull | Siouxsie and the Banshees | Aretha Franklin | Nico | Lizzy Mercier Descloux | Laurie Anderson | Janis Joplin | Joan Baez | Nina Hagen | Betty Davis | Patti Smith | Tina Turner | production Groupe Émile Dubois / Cie Jean-Claude Gallotta coproduction MCB° Bourges, Scène nationale, Théâtre du Rond-Point, Théâtre de Caen, CNDC d’Angers, Châteauvallon, scène nationale with the backing of la MC2 : Grenoble FROM SEPTEMBER 27TH TO creation 29TH 2017 ———————— [MC°B - Bourges] touring schedule >> JANUARY 10TH 2019 ———————— [ Théâtre de l’Arsenal - Val-de-Reuil ] >> JANUARY 12TH 2019 [ Espace Marcel Carné - Saint-Michel-sur-Orge ] >> FROM JANUARY 17TH TO 19 TH 2019 [ Scène nationale de Châteauvallon -

America's Changing Mirror: How Popular Music Reflects Public

AMERICA’S CHANGING MIRROR: HOW POPULAR MUSIC REFLECTS PUBLIC OPINION DURING WARTIME by Christina Tomlinson Campbell University Faculty Mentor Jaclyn Stanke Campbell University Entertainment is always a national asset. Invaluable in times of peace, it is indispensable in wartime. All those who are working in the entertainment industry are building and maintaining national morale both on the battlefront and on the home front. 1 Franklin D. Roosevelt, June 12, 1943 Whether or not we admit it, societies change in wartime. It is safe to say that after every war in America’s history, society undergoes large changes or embraces new mores, depending on the extent to which war has affected the nation. Some of the “smaller wars” in our history, like the Mexican-American War or the Spanish-American War, have left little traces of change that scarcely venture beyond some territorial adjustments and honorable mentions in our textbooks. Other wars have had profound effects in their aftermath or began as a result of a 1 Telegram to the National Conference of the Entertainment Industry for War Activities, quoted in John Bush Jones, The Songs that Fought the War: Popular Music and the Home Front, 1939-1945 (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2006), 31. catastrophic event: World War I, World War II, Vietnam, and the current wars in the Middle East. These major conflicts create changes in society that are experienced in the long term, whether expressed in new legislation, changed social customs, or new ways of thinking about government. While some of these large social shifts may be easy to spot, such as the GI Bill or the baby boom phenomenon in the 1940s and 1950s, it is also interesting to consider the changed ways of thinking in modern societies as a result of war and the degree to which information is filtered.