A View from Pakistan Clark B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

Ebrahim E. I. Moosa

January 2016 Ebrahim E. I. Moosa Keough School of Global Affairs Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies University of Notre Dame 100 Hesburgh Center for International Studies, Notre Dame, Indiana, USA 46556-5677 [email protected] www.ebrahimmoosa.com Education Degrees and Diplomas 1995 Ph.D, University of Cape Town Dissertation Title: The Legal Philosophy of al-Ghazali: Law, Language and Theology in al-Mustasfa 1989 M.A. University of Cape Town Thesis Title: The Application of Muslim Personal and Family Law in South Africa: Law, Ideology and Socio-Political Implications. 1983 Post-graduate diploma (Journalism) The City University London, United Kingdom 1982 B.A. (Pass) Kanpur University Kanpur, India 1981 ‘Alimiyya Degree Darul ʿUlum Nadwatul ʿUlama Lucknow, India Professional History Fall 2014 Professor of Islamic Studies University of Notre Dame Keough School for Global Affairs 1 Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies & Department of History Co-director, Contending Modernities Previously employed at the University of Cape Town (1989-2001), Stanford University (visiting professor 1998-2001) and Duke University (2001-2014) Major Research Interests Historical Studies: law, moral philosophy, juristic theology– medieval studies, with special reference to al-Ghazali; Qur’anic exegesis and hermeneutics Muslim Intellectual Traditions of South Asia: Madrasas of India and Pakistan; intellectual trends in Deoband school Muslim Ethics medical ethics and bioethics, Muslim family law, Islam and constitutional law; modern Islamic law Critical Thought: law and identity; religion and modernity, with special attention to human rights and pluralism Minor Research Interests history of religions; sociology of knowledge; philosophy of religion Publications Monographs Published Books What is a Madrasa? University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015): 290. -

„Marzy Mi Się Lew Boży”. Kryzys Ustrojowy W Pakistanie 1953–1955

Dzieje Najnowsze, Rocznik L – 2018, 1 PL ISSN 0419–8824 Tomasz Flasiński Instytut Historii Polskiej Akademii Nauk w Warszawie „Marzy mi się Lew Boży”. Kryzys ustrojowy w Pakistanie 1953–1955 Abstrakt: Artykuł omawia przesilenie ustrojowe w Pakistanie, które trwało w latach 1953– 1955 i zakończyło się praktyczną likwidacją ustroju demokratycznego w tym państwie. Wła- dza wykonawcza (gubernator generalny) w sojuszu z sądowniczą (Sąd Najwyższy) i wojskiem odrzuciła przejęte po Brytyjczykach niepisane zasady regulujące parlamentaryzm, a w końcu rozpędziła i sam parlament. W ostatecznym rozrachunku droga ta powiodła kraj ku autokracji. S ł owa kluczowe: Pakistan, system westminsterski, Hans Kelsen. Abstract: The article describes the crisis of Pakistani policy between 1953 and 1955, which resulted de facto in the liquidation of democracy. The executive power (Governor-General) allied with the judicial one (Supreme Court) and the army to get rid of the unwritten princi- ples, taken over from the British, regulating the parliamentary order, and fi nally dissolved the Parliament itself. Ultimately, it led the country to autocracy. Keywords: Pakistan, Westminster system, Hans Kelsen. 12 VII 1967 r. do willi Mohammada Ayuba Khana w górskim kurorcie Murree przyszedł na kolację Muhammad Munir. Pierwszy z wymienionych, od dziewięciu lat – dokładniej od 27 X 1958 r., gdy obalił swego poprzed- nika Iskandra Mirzę – sprawujący dyktatorską władzę nad Pakistanem, powoli tracił w kraju mir po niedawnej, przegranej wojnie z Indiami; drugi, w 1962 r. minister prawa w jego rządzie, a przedtem (1954–1960) prezes Sądu Najwyższego, był już politycznym emerytem, gnębionym przez choroby. Konwersacja zeszła na temat, o którym w tej sytuacji obaj panowie mogli już rozmawiać zupełnie szczerze: zamach stanu Iskandra Mirzy, który 8 X 1958 r. -

Emergence of Women's Organizations and the Resistance Movement In

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 19 | Issue 6 Article 9 Aug-2018 Defying Marginalization: Emergence of Women’s Organizations and the Resistance Movement in Pakistan: A Historical Overview Rahat Imran Imran Munir Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Imran, Rahat and Munir, Imran (2018). Defying Marginalization: Emergence of Women’s Organizations and the Resistance Movement in Pakistan: A Historical Overview. Journal of International Women's Studies, 19(6), 132-156. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol19/iss6/9 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2018 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Defying Marginalization: Emergence of Women’s Organizations and the Resistance Movement in Pakistan: A Historical Overview By Rahat Imran1 and Imran Munir2 Abstract In the wake of Pakistani dictator General-Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamization process (1977-1988), the country experienced an unprecedented tilt towards religious fundamentalism. This initiated judicial transformations that brought in rigid Islamic Sharia laws that impacted women’s freedoms and participation in the public sphere, and gender-specific curbs and policies on the pretext of implementing a religious identity. This suffocating environment that eroded women’s rights in particular through a recourse to politicization of religion also saw the emergence of equally strong resistance, particularly by women who, for the first time in Pakistan’s history, grouped and mobilized an organized activist women’s movement to challenge Zia’s oppressive laws and authoritarian regime. -

In the Supreme Court of Bangladesh High Court Division (Special Original Jurisdiction)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BANGLADESH HIGH COURT DIVISION (SPECIAL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION) Writ Petition No. 696 of 2010 In the matter of: An application under Article 102(2)(a)(ii) of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh And In the matter of: Siddique Ahmed. ... Petitioner -Versus- Bangladesh, represented by the Secretary Ministry of law, justice and Parliamentary Affairs, Bangladesh Secretariat, P.S.-Ramna and District-Dhaka and others. ....Respondents Mr. Mirza Ali Mahmood, Advocate. ...For the petitioner Mr. Mahbubey Alam, Attorney General Mr.Akram Hossain Chowdhury Mr.Karunamoy Chakma Mr.Bhisma Dev Chakravarty Ms.Promila Biswas Ms.Shakila Rowshan Jahan Deputy Attorneys General Mr.Ekramul Haque Md.Diliruzzaman Ms. Kasifa Hossain Assistant Attorneys General And Mr.M.K.Rahman, Additional Attorney General with Mr.Mostafa Zaman Islam Deputy Attorney General Mr.S.M.Nazmul Huq Assistant Attorney General ... For respondent no.1. Mr. Murad Reza, Additional Attorney General with Mr. Md. Nazrul Islam Talukder Mr. Md. Motaher Hossain Sazu, =2= Mr. M. Khurshid Alam sarker, Mr. Mahammad Selim .... Deputy Attorneys General Mr. Delowar Hossain Samaddar, A.A.G Mr. A.B.M. Altaf Hossain, A.A.G Mr. Amit Talukder, A.A.G Mr. Md. Shahidul Islam Khan, A.A.G Ms. Purabi Saha, A.A.G Ms. Fazilatunessa Bappy, A.A.G ... For the respondents No.2 Mr. M. Amir-Ul Islam, Senior Advocate Mr. A.F.M. Mesbahuddin, Senior Advocate Mr. Abdul Matin Khasru, Senior Advocate Mr. Yusuf Hossain Humayun, Advocate ......As Amicus Curiae Heard on 08.07.10, 26.07.10, 27.07.10, 10.08.10, 16.08.10, 25.8.10 and Judgment on 26.08.2010 . -

Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: a Study Of

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 19, Issue 1 1995 Article 5 Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud∗ ∗ Copyright c 1995 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud Abstract Pakistan’s successive constitutions, which enumerate guaranteed fundamental rights and pro- vide for the separation of state power and judicial review, contemplate judicial protection of vul- nerable sections of society against unlawful executive and legislative actions. This Article focuses upon the remarkably divergent pronouncements of Pakistan’s judiciary regarding the religious status and freedom of religion of one particular religious minority, the Ahmadis. The superior judiciary of Pakistan has visited the issue of religious freedom for the Ahmadis repeatedly since the establishment of the State, each time with a different result. The point of departure for this ex- amination is furnished by the recent pronouncement of the Supreme Court of Pakistan (”Supreme Court” or “Court”) in Zaheeruddin v. State,’ wherein the Court decided that Ordinance XX of 1984 (”Ordinance XX” or ”Ordinance”), which amended Pakistan’s Penal Code to make the public prac- tice by the Ahmadis of their religion a crime, does not violate freedom of religion as mandated by the Pakistan Constitution. This Article argues that Zaheeruddin is at an impermissible variance with the implied covenant of freedom of religion between religious minorities and the Founding Fathers of Pakistan, the foundational constitutional jurisprudence of the country, and the dictates of international human rights law. -

Judicial Law-Making: an Analysis of Case Law on Khul' in Pakistan

Judicial Law-Making: An Analysis of Case Law on Khul‘ in Pakistan Muhammad Munir* Abstract This work analyses case law regarding khul‘ in Pakistan. It is argued that Balqis Fatima and Khurshid Bibi cases are the best examples of judicial law- making for protecting the rights of women in the domain of personal law in Pakistan. The Courts have established that when the husband is the cause of marital discord, then he should not be given any compensation; and that the mere filing of a suit for khul‘ by the wife means that hatred and aversion have reached a degree sufficient for courts to grant her the separation she is seeking by resorting to her right of khul‘. The new interpretation of section 10(4) of the West Pakistan Family Courts Act, 1964 by Courts in Pakistan is highly commendable. Key words: khul‘, Pakistan, Muslim personal law, judicial khul‘, case law. * [email protected] The author, is Associate Professor at Faculty of Shari‘a & Law, International Islamic University, Islamabad, and Visiting Professor of Jurisprudence and Islamic Law at the University College, Islamabad. He wishes to thank Yaser Aman Khan and Hafiz Muhammad Usman for their help. He is very thankful to Professor Brady Coleman and Muhammad Zaheer Abbas for editing this work. The quotations from the Qur’an in this work are taken, unless otherwise indicated, from the English translation by Muhammad Asad, The Message of the Qur’an (Wiltshire: Dar Al-Andalus, 1984, reprinted 1997). Islamabad Law Review Introduction The superior Courts in Pakistan have pioneered judicial activism1 regarding khul‘. -

Law Review Islamabad

Islamabad Law Review ISSN 1992-5018 Volume 1, Number 1 January – March 2017 Title Quarterly Research Journal of the Faculty of Shariah & Law International Islamic University, Islamabad ISSN 1992-5018 Islamabad Law Review Quarterly Research Journal of Faculty of Shariah& Law, International Islamic University, Islamabad Volume 1, Number 1, January – March 2017 Islamabad Law Review ISSN 1992-5018 Volume 1, Number 1 January – March 2017 The Islamabad Law Review (ISSN 1992-5018) is a high quality open access peer reviewed quarterly research journal of the Faculty of Shariah & Law, International Islamic University Islamabad. The Law Review provides a platform for the researchers, academicians, professionals, practitioners and students of law and allied fields from all over the world to impart and share knowledge in the form of high quality empirical and theoretical research papers, essays, short notes/case comments, and book reviews. The Law Review also seeks to improve the law and its administration by providing a forum that identifies contemporary issues, proposes concrete means to accomplish change, and evaluates the impact of law reform, especially within the context of Islamic law. The Islamabad Law Review publishes research in the field of law and allied fields like political science, international relations, policy studies, and gender studies. Local and foreign writers are welcomed to write on Islamic law, international law, criminal law, administrative law, constitutional law, human rights law, intellectual property law, corporate law, competition law, consumer protection law, cyber law, trade law, investment law, family law, comparative law, conflict of laws, jurisprudence, environmental law, tax law, media law or any other issues that interest lawyers the world over. -

Defining Shariʿa the Politics of Islamic Judicial Review by Shoaib

Defining Shariʿa The Politics of Islamic Judicial Review By Shoaib A. Ghias A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Malcolm M. Feeley, Chair Professor Martin M. Shapiro Professor Asad Q. Ahmed Summer 2015 Defining Shariʿa The Politics of Islamic Judicial Review © 2015 By Shoaib A. Ghias Abstract Defining Shariʿa: The Politics of Islamic Judicial Review by Shoaib A. Ghias Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy University of California, Berkeley Professor Malcolm M. Feeley, Chair Since the Islamic resurgence of the 1970s, many Muslim postcolonial countries have established and empowered constitutional courts to declare laws conflicting with shariʿa as unconstitutional. The central question explored in this dissertation is whether and to what extent constitutional doctrine developed in shariʿa review is contingent on the ruling regime or represents lasting trends in interpretations of shariʿa. Using the case of Pakistan, this dissertation contends that the long-term discursive trends in shariʿa are determined in the religio-political space and only reflected in state law through the interaction of shariʿa politics, regime politics, and judicial politics. The research is based on materials gathered during fieldwork in Pakistan and datasets of Federal Shariat Court and Supreme Court cases and judges. In particular, the dissertation offers a political-institutional framework to study shariʿa review in a British postcolonial court system through exploring the role of professional and scholar judges, the discretion of the chief justice, the system of judicial appointments and tenure, and the political structure of appeal that combine to make courts agents of the political regime. -

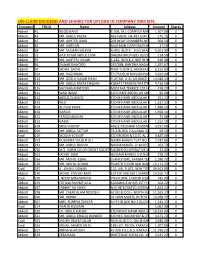

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

Legal, Judicial and Interpretive Trends in Pakistan

Development of Khul‘ Law: Legal, Judicial and Interpretive Trends in Pakistan Muhammad Ahmad Munir Institute of Islamic Studies McGill University, Montreal January 2020 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Muhammad Ahmad Munir, 2020 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Résumé .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. 6 A Note on Transliteration .................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 9 The Question of Ijtihād: What is Ijtihād? ........................................................................................... 13 The ‘Ulamā’ in Modern Pakistan......................................................................................................... 19 Literature Review ................................................................................................................................. 26 Chapter Outline ................................................................................................................................... -

Constitutional Order in Pakistan: the Dynamics of Exception

CONSTITUTIONAL ORDER IN PAKISTAN: THE DYNAMICS OF EXCEPTION, VIOLENCE AND HIGH TREASON A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I OF MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE May 2012 By Syed Sami Raza Dissertation Committee: Michael J. Shapiro, Chairperson Roger Ames Manfred Henningsen Sankaran Krishna Nevzat Soguk TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………………………………………iii Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… v Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...1 I. Disruption of the Constitutional Order and the State of Exception 1. Disruption of Pakistan’s and other Post-Colonial States’ Constitutional Order: Courts and Constitutional Theory……………………..24 2. Disruption of Constitutional Order in Pakistan: Figuring the Locus of the State of (Religious) Exception…………………………………………………..72 II. Disruption of the Constitutional Order and the Law of High Treason 3. Disruption of the Constitutional Order in Pakistan: A Critique of the Law of High Treason…………………………………………………………………………100 4. Law of High Treason, Anti-Terrorism Legal Regime in Pakistan, and Global Paradigm of Security………………………………………………………..148 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...196 191 Table of Cases …………………………………………………………………………………………………………203 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………………………………206 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my adviser—Michael J. Shapiro—for being friendly and supportive throughout the program. Without his continuous support, it would have been difficult to finish the program in four and a half years. As I appreciate Mike’s moral support, I also appreciate his academic and intellectual mentoring. In his classes and lectures, I acquired the taste for micro-politics, cinematic political thought, and critical methods. The reader will notice that the methodology of the dissertation is informed of critical methods, albeit the subject matter revolves around constitutional politics and theory.