Human Rights and Jainism—A Comparative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Antiquty of Jainism

Jainism : An Image of Antiquity Published by Shri Jain Swetamber Khartargachha Sangha, Kolkata An analytical study of the historicity, antiquity and originality Chaturmass Prabandh Samiti of the religion of Jainism of a global perspective Sheetal Nath Bhawan Gauribari Lane Kolkata - 700 004 c Dr. Lata Bothra Printed in October 2006 by : Dr. Lata Bothra Type Setting Jain Bhawan Computer Centre P-25, Kalakar Street Kolkata - 700 007 Phone : 2268-2655 Printed by Shri Bivas Datta Arunima Printing Works 81, Simla Street Kolkata - 700 006 Shri Jain Swetamber Khartargachha Sangha, Kolkata Chaturmas Prabandh Samiti Price Kolkata Rupees Fifty only continents of the worlds, regarding Jainism. Jainism is a religion which is basically revolving within the PREFACE centrifugal force of Non-violence (Ahimsa), Non- receipt (Aparigraha) and the multizonal view Through the centuries, Jainism has been the (Anekantvad), through which the concept of global mainstay of almost every religion practiced on this planet. tolerance bloomed forth. Culturally, the evidences put forward by the There was a time splendour of Jainism, as a archaeological remnants almost all over the world starting religion and an ethical lifestyle was highly prevalent in from Egypt and Babylon to Greece and Russia inevitably the early days of our continental history. The remnants prove that Jainism in its asceticism was practiced from of antiquity portray a vivid image of the global purview prehistoric days. For what reason, till today, the Jaina whereby one can conclude that Jainism in different researchers have not raised their voice and kept mum forms and images was observed in different parts of about these facts, is but a mystery to me. -

JAINISM 101 a Scientific Approach

JAINISM 101 A Scientific Approach !!Jai Jinedra !! (Greetings) Hemendra Mehta Original by Sudhir M. Shah nmae Airh<ta[<. namo arihant˜õaÕ. nmae isÏa[<. namo siddh˜õaÕ. nmae Aayirya[<. namo ˜yariy˜õaÕ. nmae %vJHaya[<. namo uvajjh˜y˜õaÕ. nmae lae@ sVv£ sahU[<. namo loae savva s˜huõaÕ. Two Beliefs 1. Taught in Indian Schools 1. Hinduism is an ancient religion 2. Jainism is an off-shoot of Hinduism 3. Mahavir and Buddha started their religions as a protest to Vedic practices Two Beliefs 2. Jain Belief 1. Jainism is millions of year old 2. Jain religion has cycles of 24 Tirthankaras 1st Rishabhdev 24th Mahavirswami 3. Rishabhdev established agriculture, family system, moral standards, law, & religion Time Chart ARYANS ARRIVE RIKHAVDEV PERIOD MAHAVIR / BUDDHA INDUS VALLEY PERIOD CHRIST 6500 BCE 500 CE 1000 BCE 000 8,500 Yrs. ago 1500 Yrs. ago 3000 Yrs. ago 2000 Yrs. ago 2500 BCE 1500 BCE 500 BCE 4500 Yrs. ago 3500 Yrs. ago 2500 Yrs. ago Jain Religion Basic Information: • 10 million followers • Two major branches ¾ Digambar ¾ Shwetamber What is Religion? According to Mahavir swami “The true nature of a substance is a religion” Religion reveals • the true nature of our soul, and • the inherent qualities of our soul Inherent Qualities of our Soul Infinite Knowledge Infinite Perception Infinite Energy Infinite Bliss What is Jainism? A Philosophy of Living – Jains: Follow JINA, the conqueror of Inner Enemies – Inner Enemies (Kashays): • Anger (Krodh) • Greed (lobh) • Ego (maan) • Deceit (maya) – Causes: Attachment (Raag) and Aversion (Dwesh) -

Nonviolence in the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist Traditions Dr

1 Nonviolence in the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist traditions Dr. Vincent Sekhar, SJ Arrupe Illam Arul Anandar College Karumathur – 625514 Madurai Dt. INDIA E-mail: [email protected] Introduction: Religion is a human institution that makes sense to human life and society as it is situated in a specific human context. It operates from ultimate perspectives, in terms of meaning and goal of life. Religion does not merely provide a set of beliefs, but offers at the level of behaviour certain principles by which the believing community seeks to reach the proposed goals and ideals. One of the tasks of religion is to orient life and the common good of humanity, etc. In history, religion and society have shaped each other. Society with its cultural and other changes do affect the external structure of any religion. And accordingly, there might be adaptations, even renewals. For instance, religions like Buddhism and Christianity had adapted local cultural and traditional elements into their religious rituals and practices. But the basic outlook of Buddhism or Christianity has not changed. Their central figures, tenets and adherence to their precepts, etc. have by and large remained the same down the history. There is a basic ethos in the religious traditions of India, in Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism. Buddhism may not believe in a permanent entity called the Soul (Atman), but it believes in the Act (karma), the prime cause for the wells or the ills of this world and of human beings. 1 Indian religions uphold the sanctity of life in all its forms and urge its protection. -

Jain World Brochure.Indd

Jainism is the science of living . Jainworld presents Jainism in a Unique Way Jainworld is a registered Foundation (Non- www.JainWorld.com JAINISM profit, Tax exempt, Trust. IRS # 501(c) (3) Jainism is one of the oldest living religions. Most envi- 48-1266905 ) in USA & other countries. All ronmentally friendly, ecology protecting and indepen- donations in USA are tax exempt. Your entry point dent religion with intrinsic respect and equality for all living beings (including animals). There is a provision for www.jainworld.com the highest level of enlightment for all in a scientific way. to the exciting world www.jainworld.net Man himself, and he alone, is responsible for all that is good or bad in his life. Actions, thought and speech along www.jainworld.org of Jainism with passions result in karmas. He must remove karmas or bear their consequences at maturity. (… one of the oldest living religion) Every soul is capable of attaining perfection (i.e. infinite perception, infinite knowledge, infinite power and infi- nite bliss) if it willfully exerts in that direction. This world in full of sorrow and trouble and it is quite necessary to achieve the aim of transcendental bliss by a sure method. No God, nor His prophet or beloved can interfere with life of others. The soul, and that alone is directly and nec- essarily responsible for all that it does. God is regarded as completely unconcerned with cre- ation of the universe or with any happening in the uni- verse. The universe goes of its own accord i.e. if follows laws of nature. -

Jain Values, Worship and the Tirthankara Image

JAIN VALUES, WORSHIP AND THE TIRTHANKARA IMAGE B.A., University of Washington, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard / THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1980 (c)Roy L. Leavitt In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology & Sociology The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date 14 October 1980 The main purpose of the thesis is to examine Jain worship and the role of the Jains1 Tirthankara images in worship. The thesis argues that the worshipper emulates the Tirthankara image which embodies Jain values and that these values define and, in part, dictate proper behavior. In becoming like the image, the worshipper's actions ex• press the common concerns of the Jains and follow a pattern that is prized because it is believed to be especially Jain. The basic orientation or line of thought is that culture is a system of symbols. These symbols are implicit agreements among the community's members, agreements which entail values and which permit the Jains to meaningfully interpret their experiences and guide their actions. -

Notes on Modern Jainism

'J UN11 JUI .UBRARYQr c? IEUNIVER%. fHONVSOV | I ! 1 I i r^ 5, 3 ? \E-UNIVER. <~> **- 1 S 'OUJMVJ'iU ' il g i i i I s fc i<^ vvlOS-ANCELfX^ " - ^ <tx-N__^ # = =3 1( ^ Af-UNIVfl% il I fe ^'^ t $ ^ ^*-~- ^ ^ NOTES ON MODERN JAINISM WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE S'VETA'MBARA, DIGAMBARA AND STHA'NAKAVA'SI SECTS. BY MRS. SINCLAIR STEVENSON, M.A. (T.C.D.) SOMETIME SCHOLAR OF SOMERVILLE COLLEGE, OXFORD. OXFORD S i B. H. BLACKWELL, 50 & 51 BROAD REET LONDON SIMPKIN, MARSHALL & Co, LIMITED SURAT : IRISH MISSION PRESS 1910. Stack Annfv r 333 HVNC LIBELLVM DE TRISTS VITAE SEVERITATE CVM MEAE TVM MARITI MATR! MEMORiAE MONVMENTVM DEDICO QVAE EXEMPLVM LONGE ALIVM SECVTAE NOMEN MATERNVM TAM FELICITER ORNAVERVNT. ** 2029268 PREFACE. THESE notes on Jain ism have been compiled mainly from information supplied to me by Gujarati speaking Jaina, so it has seemed advisable to use the Gujarati forms of their technical terms. It would be impossible to issue this little book without expressing my indebtedness to the Rev. G. P. Taylor, D. D., Principal of the Fleming Stevenson Divinity College, Ahmedabad, who placed all the resources of his valuable library at my disposal, and also to the various Jaina friends who so courteously bore with my interminable questionings. I am specially grateful to a learned Jaina gentleman who read through all the MS. with me, and thereby saved me, I hope, from some of the numerous pitfalls which beset the pathway of anyone who ventures to explore an alien faith. MARGARET STEVENSON. Irish Mission, Rajkot. India. -

Living Landscapes

Introduction Yoga and Landscapes This book explores the practice of Yoga in regard to a systematic technique of performing concentration on the five elements. It examines some ideas that also concerned the pre-Socratic philosophers of Greece. Just as Thales mused about water and Heraclitus extolled the power of fire, Indian thinkers, theologians, and liturgists reflected on how the elements interweave with one another and within the human body to create the raw material for the experience of life. In a real and metaphorical sense, according to Indian thought, we live in landscapes and landscapes live in us. For more than 3,500 years, India has identified earth, water, fire, air, and space as the foundational building blocks of external reality. Starting with literary praise of these elements in the Vedas, by the time of the Buddha, the Upaniṣads, and early Jainism, this acknowledgment had grown into a systematic reflection. This book examines both the descriptions of the elements and the very technical training tools that emerged so that human beings might develop regard and consideration for them. Hindus, Buddhists, and Jain Yogis explore the human-earth relationship each in their own way. For Hindus, nature emerges as a theme in the Vedas, the Upaniṣads, the Yoga literature, the epics, and the Purāṇas. The Yogis develop a mental discipline of sustained interiorization, known as pañca mahābhūta dhāraṇā (concentration on the five great elements) and as bhūta śuddhi (purification of the elements). The Buddha himself also taught a sequential meditation on the five elements. The Jains developed their own unique reflections on nature, finding life in particles of earth, water, fire, and air. -

Jain Vishva Bharati Institute, Ladnun (Deemed University) Research Eligibility Test (Ret) - 2017 Paper – Ii Jainology and Comparative Religion & Philosophy

JAIN VISHVA BHARATI INSTITUTE, LADNUN (DEEMED UNIVERSITY) RESEARCH ELIGIBILITY TEST (RET) - 2017 PAPER – II JAINOLOGY AND COMPARATIVE RELIGION & PHILOSOPHY DATE OF EXAMINATION : JULY 27, 2017 ROLL NO. : SIG. OF INVIGILATOR TIME : 01.30 HOURS MARKS : 75 X 2 = 150 NOTE : 1. All questions are compulsory and of objective type. / lHkh iz'u vfuok;Z ,oa oLrqfu"B gSaA lHkh iz'uksa ds vad leku gaSA 2. All questions carry equal marks. / izR;sd iz'u dk ,d gh mÙkj nsuk gSA 3. Only one answer is to be given for each question. / 4. If more than one answer is marked, it would be treated as wrong answer. / ,d ls vf/kd mÙkj nsus dh n'kk esa iz'u ds mÙkj dks xyr ekuk tk;sxkA 1- tSu n'kZu ds vuqlkj bZ'oj gS&@ God is, according to Jainisim- ¼v½ txr~ dk drkZ@Creator of the world ¼c½ txr~ dk HkksDrk@Bhokta of the world ¼l½ Kkrk n`"Vk@Knower and viewer ¼n½ buesa ls dksbZ ugha@None of these ( ) 2- i pkfLrdk; dk ys[kd dkSu gS\@ Ä Who is the writer of the Panchatikaya? ¼v½ leUrHknz@Samantbhadra ¼c½ mekLokfr@Umaswati ¼l½ dqUndqUn@Kundkund ¼n½ egkizK@Mahaprajna ( ) 1 P.T.O. 3- tSu U;k; dk izFke lw= xzUFk dkSu lk gS\ / Which is the first sutra book of the Jain Nyay? ¼v½ rŸokFkZ lw=@Tattvarth Sutra ¼c½ izek.ku;rŸokyksd@Pramannayatattvalok ¼l½ ijh{kkeq[k lw=@Parikshamukh Sutra ¼n½ fHk{kqU;k;df.kZdk@Bhikshu-nyaykarnika ( ) 4- dkSu T;knk izkphu gS\@ Who is more ancient? ¼v½ ik'oZukFk@Parshwanath ¼c½ egkohj@Mahaveer ¼l½ gfjHknz@Haribhadra ¼n½ gsepUnz@Hemchandra ( ) 5- buesa ls fnxEcj vkpk;Z dkSu gaS\@ Which one is Digambar Acharya? ¼v½ LFkwfyHknz@Sthoolibhadra ¼c½ leUrHknz@Samantbhadra ¼l½ gsepUnz@Hemchandra ¼n½ {kekJe.k@Kshamasraman ( ) 6- buesa ls 'osrkEcj vkpk;Z dkSu gSa\@ Which one is Swetamber Acharya? ¼v½ vdyad@Aklank ¼c½ iwT;ikn@Poojyapaad ¼l½ okfnnso@Vadidev ¼n½ fo|kuUn@Vidyanand ( ) 7- fnxEcj vkxe fdl Hkk"kk esa jps x;s\@ In which language Digambar canons were composed? ¼v½ laLd`r@Sanskrit ¼c½ 'kkSjlsuh izkd`r@Shourseni Prakrit ¼l½ v/kZekx/kh izkd`r@Ardhmagdhi Prakrit ¼n½ viHkza'k@Apbhransh ( ) 2 P.T.O. -

Why Must There Be an Omniscient in Jainism?

5 WHY MUST THERE BE AN OMNISCIENT IN JAINISM? Sin Fujinaga 1. It is a well-known fact that the Jains deny the existence of God as a creator of this universe while the Hindus admit such existence. According to Jainism this universe has no beginning and no end, so no being has created it. On the other hand, the Jains are very eager to establish the existence of an omniscient person. Such a person is denied in the Hindu tradition. The Jain saviors or tirthaÅkaras are sometimes called bhagavan, a Lord. This word does not indicate a creator but rather means a respected person with all-pervading knowledge. Generally speaking, the omniscience of the tirthaÅkaras is such that they grasp each and every thing of the universe not only in the present time, but in the past and the future also. The view on the omniscience of tirthaÅkaras, however, is not ubiquitous in the Jaina tradition. Kundakunda remarks, “From the practical point of view an omniscient Lord perceives and knows all, while from the real point of view he perceives and knows his own soul.”1 Buddhism, another non-Hindu school of Indian philosophy, maintains that the founder Buddha is omniscient. In the Pali canon, the Buddha is sometimes described with the word savvaññu or sabbavid, both of which mean omniscient.2 But he is also said to recognize only the religious truth of dharma, more precisely, the four noble truths, caturaryasatya. This means that the omniscient Buddha does not need to know details of matters such as the number of insects in this world. -

The Heart of Jainism

;c\j -co THE RELIGIOUS QUEST OF INDIA EDITED BY J. N. FARQUHAR, MA. LITERARY SECRETARY, NATIONAL COUNCIL OF YOUNG MEN S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATIONS, INDIA AND CEYLON AND H. D. GRISWOLD, MA., PH.D. SECRETARY OF THE COUNCIL OF THE AMERICAN PRESBYTERIAN MISSIONS IN INDIA si 7 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME ALREADY PUBLISHED INDIAN THEISM, FROM By NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., THE VEDIC TO THE D.Litt. Pp.xvi + 292. Price MUHAMMADAN 6s. net. PERIOD. IN PREPARATION THE RELIGIOUS LITERA By J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A. TURE OF INDIA. THE RELIGION OF THE By H. D. GRISWOLD, M.A., RIGVEDA. PH.D. THE VEDANTA By A. G. HOGG, M.A., Chris tian College, Madras. HINDU ETHICS By JOHN MCKENZIE, M.A., Wilson College, Bombay. BUDDHISM By K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., Literary Secretary, National Council of Y.M.C.A., India and Ceylon. ISLAM IN INDIA By H. A. WALTER, M.A., Literary Secretary, National Council of Y.M.C.A., India and Ceylon. JAN 9 1986 EDITORIAL PREFACE THE writers of this series of volumes on the variant forms of religious life in India are governed in their work by two impelling motives. I. They endeavour to work in the sincere and sympathetic spirit of science. They desire to understand the perplexingly involved developments of thought and life in India and dis passionately to estimate their value. They recognize the futility of any such attempt to understand and evaluate, unless it is grounded in a thorough historical study of the phenomena investigated. In recognizing this fact they do no more than share what is common ground among all modern students of religion of any repute. -

Into the Future with Knowledge from Our Past

Into The Future With Knowledge from Our Past A Sourcebook for ‘VTT Scholar Quiz Competition 2007-08’ • Lessons from the Panchatantra • Potential of Ayurveda • Ancient Indian Technology • Srimad Bhagavad Gita & Lessons for Modern Management • Siri Bhoovalaya – A Unique Kannada Work of Cryptology • India’s Contribution to Linguistics • Yoga & Leadership Sponsors • Dakshinamnaya Sri Sharada Peetham, Sringeri • BMS College for Women, Bangalore • Sri Tirunarayana Trust, Bangalore For free distribution only. Not for Sale. Sourcebook and some of the presentations are also available at www.tirunarayana.org CONTENTS Preface 1 A Note to Students 2 A Brief Profile of Our Speakers at the Seminar 3 Into the Future with Knowledge from Our Past Lessons from the Panchatantra 5 Potential of Ayurveda 9 Ancient Indian Technology 13 Srimad Bhagavad Gita and Lessons for Modern Management 16 Siri Bhoovalaya – A Unique Kannada Work of Cryptology 19 India’s Contribution to Linguistics 25 Yoga & Leadership 28 PREFACE Students from twenty-two colleges and pre-university colleges, other than the BMS College for Women, which co-sponsored the programme, participated in the sixth annual Into the Future with Knowledge from Our Past seminar. A majority of the students (51.3%) was from the Commerce stream followed by Science (30.68%). However, it was encouraging to find that students from all educational streams, including professional courses like engineering, business management and computer applications, attended the seminar. While each of the topics dealt with in the seminar was rated the “most liked” by at least ten per cent of the students, Lessons from the Panchatantra (73.02%) and Srimad Bhagavad Gita and Lessons for Modern Management (30.68) appear to have been the most popular among students. -

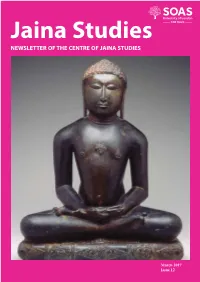

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2017 Issue 12 CoJS Newsletter • March 2017 • Issue 12 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christine Chojnacki Muni Mahendra Kumar Ratnakumar Shah Professor J. Clifford Wright (University of Lyon) (Jain Vishva Bharati Institute, India) (Pune) Chair/Director of the Centre Dr Anne Clavel Dr James Laidlaw Dr Kanubhai Sheth Dr Peter Flügel (Aix en Province) (University of Cambridge) (LD Institute, Ahmedabad) Dr Crispin Branfoot Professor John E. Cort Dr Basile Leclère Dr Kalpana Sheth Department of the History of Art (Denison University) (University of Lyon) (Ahmedabad) and Archaeology Dr Eva De Clercq Dr Jeffery Long Dr Kamala Canda Sogani Professor Rachel Dwyer (University of Ghent) (Elizabethtown College) (Apapramśa Sāhitya Academy, Jaipur) South Asia Department Dr Robert J. Del Bontà Dr Andrea Luithle-Hardenberg Dr Jayandra Soni Dr Sean Gaffney (Independent Scholar) (University of Tübingen) (University of Marburg) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Saryu V. Doshi Professor Adelheid Mette Dr Luitgard Soni Dr Erica Hunter (Mumbai) (University of Munich) (University of Marburg) Department of the Study of Religions Professor Christoph Emmrich Gerd Mevissen Dr Herman Tieken Dr James Mallinson (University of Toronto) (Berliner Indologische Studien) (Institut Kern, Universiteit Leiden) South Asia Department Dr Anna Aurelia Esposito Professor Anne E. Monius Professor Maruti Nandan P. Tiwari Professor Werner Menski (University of Würzburg) (Harvard Divinity School) (Banaras Hindu University) School of Law Dr Sherry Fohr Dr Andrew More Dr Himal Trikha Professor Francesca Orsini (Converse College) (University of Toronto) (Austrian Academy of Sciences) South Asia Department Janet Leigh Foster Catherine Morice-Singh Dr Tomoyuki Uno Dr Ulrich Pagel (SOAS Alumna) (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris) (Chikushi Jogakuen University) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Lynn Foulston Professor Hampa P.