Henry Namesakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September/October 2019 Issue

Archibald and MACOA East Friends September/October 2 0 1 9 Come Travel With Us! (not just for members) Lancaster, PA and Historic Philadelphia! September 29 - October 5, 2019 $1300 per person single occupancy; $1050 per person double or triple occupancy Your 7 days/6 nights package includes 6 nights of hotel accommodations, 6 breakfasts at your hotel, 1 wonderful lunch and 3 dinners to include 2 Amish style dinner feasts, and 2 evening receptions at your hotel including hot food and beverages. We will watch the production of “Noah - Two by Two, The Voyage Began” at the fabulous Sight and Sound Theater, have a guided tour of Amish Farmlands in Lancaster County, a guided tour of Historic Philadelphia, a guided tour of the Gettysburg National Military Park, we will enjoy a visit to the Kitchen Kettle Village, take a 45 minute ride through the tranquil Amish countryside on the Strasburg Rail Road, and a visit to Hershey’s Chocolate World. Standard taxes, meal gratuities, baggage handling and motor coach transportation is included. WE STILL HAVE ROOM FOR TRAVELERS Full payment is due now. Make your reservation TODAY by calling the Archibald Center (334) 240-6767. (Travel Protection can be purchased at $92.00/person for double and triple occupancy; $119.00 for single occupancy. If you wish to purchase Travel Protection, please send in a separate check made payable to PML Travel & Tours.) The Archibald Senior Center is headed to the Shenandoah Valley and the Blue Ridge Mountains April 19 – April 24, 2020 for 6 days and 5 nights. -

National Speleologi'c-Al Society

Bulletin Number Five NATIONAL SPELEOLOGI'C-AL SOCIETY n this Issue: CAVES IN WORLD HISTORY . B ~ BERT MORGAN THE GEM OF CAVES' . .. .. • B DALE WHITE CA VE FAUN A, with Recent Additions to the Lit ture Bl J. A. FOWLER CAT ALOG OF THE SOCIETY LJBR R . B)' ROBERT S. BRAY OCTOBER, 1943 PRJ E 1.0 0 . ------------------------------------------- .-'~ BULLETIN OF THE NATIONAL SPELEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Issue Number Five October, 1943 750 Copies. 64 Pages Published sporadically by THE NATIONAL SPELEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, 510 Scar Building, Washington, D. c., ac $1.00 per copy. Copyrighc, 1943, by THE NATIONAL SPELEOLOGICAL SOCIETY. EDITOR: DON BLOCH 5606 Sonoma Road, Bethesda-14, Maryland ASSOCIATE EDITORS: ROBERT BRAY WILLIAM J. STEPHENSON J. S. PETRIE OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN *WM. ]. STEPHENSON J. S. PETR'IE *LEROY FOOTE F. DURR President Vice·Prcsidet1l & Secretary Treasurer Pina~iaJ Sect'eIM"J 7108 Prospect Avenue 400 S. Glebe Road R. D. 3 2005 Kansas Avenue Richmond, Va. Arlin-glon, Va. Waterbury, Conn. Richmond, Va. Archeology Fauna Hydrology Programs &. Activities FLOYD BARLOGA JAMES FOWLER DR. WM. M. MCGILL DR. JAMES BENN 202·8 Lee Boulevard 6420 14th Street 6 Wayside Place, University U. S. Nat. Museum Arlington, Va. Washington, D . C. Charlottesville, Va. Washington, D. C. Bibliography &. Library Finance Mapping PubliCity *ROBERT BRAY *l.EROY FOOTB GBORGE CRABB *·Lou KLBWEJ.t R. F. D. 2 R. F. D. 3 P. O. Box 791 Toledo Blade Herndon, Va. Waterbury, Conn. Blacksburg, Va. Toledo, Ohio BuIletin &. Publications Folklore Metnbership DON BLOCH "'CLAY PERRY SAM ALLBN RECORDS 5606 Sonoma Road East Acres 1226 Wel.Jesley Avenue *FLORENCE WHITLI!Y Deorhesda, Md. -

NCA Cave Talk Route 9, Box 106 NATIONAL CAVES ASSOCIATION Mcminnville, TN 37110 (615) 668-3925 June 26, 1991

BARBARA MUNSON, Coordinator NCA Cave Talk Route 9, Box 106 NATIONAL CAVES ASSOCIATION McMinnville, TN 37110 (615) 668-3925 June 26, 1991 NCAIN PUERTORICO November 4th through 7th, 1991 Pedro Hernandez-Purcell and the folks at RIO CAllUYCAVEPARKare putting together an exciting 1991 UCAAnnual Convention for us. Activities lIill start first thing the morning of November 4th from San Juan, and continue through the evening of the 7th in Arecibo. In addition to our regular Business lIeetings and the Roundtable discussions, lie lIill be visiting interesting places and lIill also be hosted at numerous delightful activities. Airline and car rental discounts are being arranged. Registration \lill be through the NCAoffice. All this information, and mOle, lIill be included in the Illr'ORJIATIONREGIS1'RATIONPACKETIlhich lIill be available shortly. NCAINSllilANCEPROGRAlf Our National Caves Association Risk Management & Insurance Coverage Program is nml in place. This is the culmination of lots of study and hard 1I0rk by Harrison Terk, our NCAInsurance Steering Committee, the Executive Committee, and Keith Dobrolinsky of the Arthur J. Gallagher Co. Fireman's Fund lIill be the carrier. Excellent coverage and some special featul"eS are offered at rates IIhich lIill benefit both our members and the NCA. He've sent Premium Quotation Applications to members IIhose liability insurance \lill be up for rene\lal in the near future. A booklet outlining the entire program is being prepared and \lill be mailed to all our members in mid-July. Application forms l/ill be included Ilith the booklet. This is a great insurance program, it is also an example of the NCAassuming a leadership role in the shall cave industry. -

Luray & Page County

DESTINATION GUIDE Visit LURAY & PAGE COUNTY VIRGINIA Virginia’s Home to the Shenandoah National Park WELCOME Luray-Page County Chamber of Commerce & Visitor Center Page County is nestled between the Blue Ridge and Massanutten Mountains in a portion of the Shenandoah Valley known as the Page Valley. The County is comprised of the three towns of Luray, Stanley, and Shenandoah, each with its own downtown, boutique shops, mom-and-pop restaurants, and outdoor recreation. Home to picturesque farms, historic inns, and country roads, winding their ways to the base of the mountain ranges, there are breathtaking views around every turn. Outdoor recreation lovers will find everything they need for true peace and relaxation in the valley. Escape from the city to the Shenandoah River for canoeing, kayaking, or leisurely tubing. Discover the Shenandoah National Park for a hike along the Appalachian Trail or any number of other trails. Sit horseback or astride an ATV and as a guide points out tracks and views not attainable by foot or car. Head underground in the Luray Caverns to explore the limestone caves the Shenandoah Valley is known for or hop on your bike and cruise through the countryside; whatever your preference, Luray-Page has the paths that will take you to one-of-a-kind experiences and memories. Visit us online at visitluraypage.com 18 Campbell Street, Luray, VA 22835 Tel: (540) 743-3915 • Fax: (540) 743-3944 • Email: [email protected] • Open Daily 9 AM to 5 PM Marketing and editorial by Gina Hilliard, President, and Clancey Arnold, Membership Development & Investment Administrator; design by Page Marketing Solutions; printing by Progress Printing Plus; sunrise photo by Neal Lewis, SNP 2 540.743.3915 WELCOME 2 ATTRACTIONS 4 DINING 11 LODGING 14 SHOPPING 25 SUPPORT SERVICES 28 SPECIAL OCCASIONS 30 EVENTS 33 VisitLurayPage.com 3 ATTRACTIONS, RECREATIONS & ARTS Appalachian Adventures Caverns Country Club 3095 US Highway 211 East, Luray, VA 22835; (540) 743-7311 910 T.C. -

AIP Grants Awarded by State: FY 2014 AIP Grants Awarded in FY 2014 by State

FAA Airports AIP Grants Awarded by State: FY 2014 AIP Grants Awarded in FY 2014 by State Service Grant Federal City Airport/Project Location Description of Project Level No. Funds Alabama General Abbeville Abbeville Municipal 8 420,944 Construct Building, Improve Airport Drainage Aviation General Alabaster Shelby County 17 37,800 Construct Building Aviation Albertville Regional-Thomas General Albertville 24 525,542 Rehabilitate Apron J Brumlik Field Aviation General Aliceville George Downer 12 41,400 Construct Fuel Farm Aviation South Alabama Regional at General Andalusia 19 290,345 Improve Airport Erosion Control Bill Benton Field Aviation General Anniston Anniston Regional 30 203,422 Install Guidance Signs Aviation General Bay Minette Bay Minette Municipal 10 2,316,930 Construct Taxiway Aviation Bessemer Bessemer Reliever 13 67,500 Rehabilitate Apron, Rehabilitate Taxiway Birmingham-Shuttlesworth Birmingham Primary 92 3,607,326 Expand Terminal Building International Birmingham-Shuttlesworth Improve Airport Miscellaneous Improvements, Birmingham Primary 93 1,982,389 International Improve Runway Safety Area, Rehabilitate Taxiway Total AIP Grant Funds Awarded 11/13/2017 Page 1 of 133 FY 2014 APP-500 Service Grant Federal City Airport/Project Location Description of Project Level No. Funds Birmingham-Shuttlesworth Birmingham Primary 94 600,000 Update Airport Master Plan Study International Birmingham-Shuttlesworth Acquire Land for Noise Compatibility within 65 - 69 Birmingham Primary 95 1,904,891 International DNL General Brewton Brewton -

Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District

Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District Belle Grove Plantation Burwell-Morgan Mill 336 Belle Grove Road 15 Tannery Lane Middletown, VA 22645 Millwood, VA 22646 540-869-2028/[email protected] 540-837-1799/[email protected] www.bellegrove.org Open May-November, Friday Noon-5pm, Saturday 10am-5pm, Open late March-early November; Sunday Noon-5pm Monday-Saturday 10am-4pm, Sunday 1-5pm Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park Clarke County Historical Association and Museum Visitor Contact Station 32 East Main Street 7712 Main Street Berryville, VA 22611 Middletown, VA 22645 540-955-2600/[email protected] 540-869-3051 www.clarkehistory.org www.nps.gov/cebe Open Tuesday-Saturday, 11am - 4pm Open Daily 8:30am-4:30pm Edinburg Mill Grand Caverns 214 South Main St. 5 Grand Caverns Drive Edinburg, VA 22824 Grottoes, VA 24441 540-984-8400 540-249-5705/[email protected] www.edinburgmill.com www.grandcaverns.com Open Monday- Saturday, 10am-5pm; Sunday, Noon-5pm Open 9am-5pm daily Hardesty-Higgins House Visitor Center and The Heritage Museum Civil War Orientation Center 382 High Street 212 S. Main Street Dayton, VA Harrisonburg, VA 22801 540-879-2681 540-432-8935 www.heritagecenter.com/[email protected] www.harrisonburgtourism.com Open Tuesday-Saturday, 10am-4pm Open daily, 9am-5pm Highland County Museum Kernstown Battlefield on Pritchard-Grim Farm Highland Museum & Heritage Center and Civil War Orientation 610 Battle Park Drive Center Winchester, VA 22601 161 Mansion House Road 540-869-2896/[email protected] McDowell, VA 24458 www.kernstownbattle.org 540-396-4478/[email protected] Open May-October; Sat 10am-4pm, Sun Noon-4pm www.highlandcountyhistory.com Open March 1 - Oct. -

Geologic Site of the Month: Maine's Enchanted Cave

Maine's Enchanted Cave Maine Geological Survey Maine Geologic Facts and Localities February, 2007 Maine's Enchanted Cave Text by Daniel B. Locke Maine Geological Survey Maine Geological Survey, Department of Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry 1 Maine's Enchanted Cave Maine Geological Survey Maine Caves Maine caves are generally categorized as sea caves, talus/fissure caves, and solution caves. Sea caves form along zones of weakness in the rock which may include areas of cracks or where there are differences in abrasive resistance. Since the action of waves is concentrated at the base of cliffs, an overhang forms (Figure 1). The Ovens of Mount Desert Island are examples of Maine sea caves. Figure by Daniel Locke B. by Daniel Figure Figure 1. Sea caves created by wave action along zones of weakness in the rock. Maine Geological Survey, Department of Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry 2 Maine's Enchanted Cave Maine Geological Survey Maine Caves Talus or fissure caves are typically found in various types of granite and are caused by large slabs of rock and boulders which have shifted as a result of slides and collapses (Figure 2). An example of a Maine talus cave includes the Allagash Ice Cave which is noted for being the longest of its type in New England. Figure by Daniel Locke B. by Daniel Figure Figure 2. Talus cave formed by the collapse of large slabs of rock. Maine Geological Survey, Department of Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry 3 Maine's Enchanted Cave Maine Geological Survey Maine Caves Solution caves in Maine are formed in carbonate rocks, such as limestone and marble, by the action of moving water. -

Notable Caves of the World

NOTABLE CAVES OF THE WORLD Name Location Interesting Facts • ceiling paintings discovered in 1879 by an eight-year- Spain Altamira old girl 43.377 °N, 4.123 °W • noted for its many cave paintings New Mexico • altitude and insulating effects of lava cave walls Bandera Volcano Ice Cave 34.991 °N, 108.083 °W maintain blue-green ice formations year-round Italy • sea cave that seems to be lit from underwater giving Blue Grotto 40.561 °N, 14.206 °E it its beautiful blue color • largest cavern in the United States (One chamber, the New Mexico Carlsbad Caverns Big Room, could hold an aircraft carrier!) 32.177 °N, 104.441 °W • contains Indian wall paintings Austria Eisriesenwelt • world’s largest ice cave—42 km in length 47.503 °N, 13.189 °E • cave paintings discovered in 1940 France • famous Hall of Bulls Grotto de Lascaux 45.054 °N, 1.168 °E • original caves closed due to deterioration caused by visitors Abkhazia, Georgia Krubera Cave • deepest known cave in the world at 2197 m 43.409 °N, 40.361 °E California Lava Beds National Monument • world’s largest collection of volcanic caves 41.707 °N, 121.514 °W • many spectacular formations Virginia Luray Caverns • a stalacpipe organ that creates musical notes by 38.664 °N, 78.484 °W striking hollow stalactites Kentucky • most extensive known cave in the world, with Mammoth Cave 37.186 °N, 86.101 °W 652 km of passages and rooms China Miao Room of the Gebihe Cave • large cave chamber—852 m × 191 m × 66 m 25.677 °N, 106.265 °E Mexico Ox Bel Ha • most extensive known underwater cave—270 km 20.160 °N, 87.488 °W • desert caves near the Dead Sea where ancient scrolls Israel Qumran Caves were found, including parts of all Old Testament 31.741 °N, 35.459 °E books except Esther Borneo • world’s largest known cave chamber by area— Sarawak Chamber 4.024 °N, 114.824 °E 600 m × 435 m × 115 m New Zealand • Glowworms cling to the ceiling, giving the Waitomo Caves 38.261 °S, 175.103 °E appearance of stars in a night sky. -

An Example from Recrystallized Speleothems from Wadi Sannur Cavern, Egypt

L. Bruce Railsback, Adel A. Dabous, J.K. Osmond, and C.J. Fleisher - Petrographic and geochemical screening of speleothems for U-series dating: An example from recrystallized speleothems from Wadi Sannur Cavern, Egypt. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies 64(2): 108-116. PETROGRAPHIC AND GEOCHEMICAL SCREENING OF SPELEOTHEMS FOR U-SERIES DATING: AN EXAMPLE FROM RECRYSTALLIZED SPELEOTHEMS FROM WADI SANNUR CAVERN, EGYPT L. BRUCE RAILSBACK1, ADEL A. DABOUS2, J.K. OSMOND2, AND C.J. FLEISHER1 1Department of Geology, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602-2501 USA 2Department of Geological Sciences, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida 32306-4100 USA Petrographic and geochemical analyses of four speleothems from Wadi Sannur Cavern in eastern Egypt show that petrography and geochemistry can provide a useful way to screen speleothems prior to dating via U-series analysis. The speleothems vary from inclusion-rich zoned calcite to clear featureless calcite. U concentrations (ranging from 0.01-2.65 ppm) and Sr concentrations (ranging from 0.00-0.11 wt%) are greater in inclusion-rich zoned calcite. U concentrations are also greater in speleothems with small (<1.2 mm wide) columnar calcite crystals than in speleothems with larger crystals. Mg concentrations in the speleothems range from 0.2-2.3 mol% MgCO3 and show no significant relationship to petrogra- phy at the microscopic scale. Geochemical considerations suggest that the Wadi Sannur speleothems were originally mostly aragonite, and that all four have undergone recrystallization. More generally, they suggest that coarse clear columnar calcite and large (>1.0 ppm) ranges of U concentration are warning signs of recrystallization and U loss. -

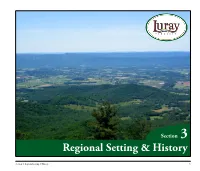

Regional Setting & History

Section 3 Regional Setting & History Section 3: Regional Setting & History 9 Regional Setting The Town of Luray is located in Page County, and is situated near the geographic center of the County.. This location has contributed favorably to Luray’s function as a cultural and economic center for the surrounding region. The 2010 U.S. Census reported that the Town of Luray had a population of 4,895 residents. Page County lies in the eastern half of the Shenandoah Valley. On its eastern border are the Blue Ridge Mountains; on its western border is the Massanutten Mountain range; and in between flows the South Fork of the Shenandoah River. The mountains and Topography & Climate valley area abound in scenic beauty and offer a multitude of natural Luray’s topography is primarily rolling hills with elevations varying outdoor recreational opportunities. Shenandoah National Park, from 800 feet to 1,000 feet. The surrounding landscape in Page with its mountain crest of Skyline Drive, extends along the Blue County is mountainous terrain with elevations as high as 4,000 Ridge Mountains to the east. Additionally, the Town of Luray is feet at the Hawksbill Mountain. The Hawksbill Creek flows the location of the internationally-known “Luray Caverns.” through the Town, and is a tributary of the South Fork of the Because of these and other attractions, visitors are drawn to the Shenandoah River. The Creek and the South Fork merge Luray area year-round. approximately six miles to the north of Luray. The headwaters of the Hawksbill Creek begin on the steep, wooded slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains. -

Luray Caverns—"Eighth Wonder of the World"

• VoL. LII WASHINGTON, D. C., SEPTEMBER 13, 1904 No. 37 of the existence of the Caverns, than they began limestone rocks, weathers them very rapidly. litigation to regain the property. They failed in All, doubtless, are familiar with the fact that the lower courts, but finally succeeded in getting there exist many underground streams, rivers, their claims sustained by a higher court. Mr. and lakes, and that flowing water exerts a stu- Stebbins lost heavily by the transaction; but pendous power in eroding, or wearing away and Luray Caverns—"Eighth Wonder of the later on he came into possession of the rich mine removing, great masses of rock. World" of truth embraced in the third angel's message. Now a cave is but an underground valley — a IN the beautiful Luray Valley, which forms Had he succeeded in realizing the anticipated pro- system of large ravines. If the cave hill is sub- Page County, Virginia, are found the great fits from his discovery, perhaps he would not have ject to rain torrents flowing from the surrounding limestone caverns that are said to excel all other been so ready to accept of the new-found truth. mountains, and if its strata are inclined, water known caves of the world, surpassing in beauty and variety of ornamentation, though not equaling in size, the world-famed Mam- moth Cave of Kentucky. The Luray Valley is hemmed in on every side with a rim of mountains, ranging from two thousand to four thousand feet in height. The Blue Ridge begins on the north, swings completely around the valley to the west, then the Massanutten Mountains com- plete the circle. -

Luray Caverns Blind Cave Millipede

Conservation Assessment for Luray Caverns Blind Cave Milliped (Trichopetalum whitei) (From Barr, 1973) USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region December 2001 Julian J. Lewis, Ph.D. J. Lewis & Associates, Biological Consulting 217 W. Carter Avenue Clarksville, IN 47129 [email protected] This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on the Trichopetalum whitei (Luray Caverns Blind Cave Milliped). It does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if you have information that will assist in conserving the subject community and associated taxa, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. Conservation Assessment for Luray Caverns Blind Cave Milliped (Trichopetalum whitei) 2 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................. 4 NOMENCLATURE AND TAXONOMY ......................................................... 4 DESCRIPTION OF SPECIES ........................................................................... 4 LIFE HISTORY................................................................................................... 5 HABITAT ............................................................................................................