Student Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide Nage No Kata

SOMMAIRE Qu’est ce que le Nage No Kata ? 4 Illustrations et commentaires du guide 5 Généralités sur le Nage No Kata 6 Le Nage No Kata 7 Tableau « le Nage No Kata et son intérêt pour la pratique du Judo » 24 Conclusion 28 Lexique 29 Planche Nage No Kata Ont participé à la réalisation de cet ouvrage : Michel Algisi : 7e dan, cadre technique, responsable national des katas Patrice Berthoux : 6e dan, cadre technique André Boutin : 7e dan, cadre technique Laurent Dosne : 5e dan, professeur de judo Michèle Lionnet : 6e dan, cadre technique, coordonnatrice de l’ouvrage André Parent : 5e dan, professeur de judo Louis Renelleau : 7e dan, professeur de judo Ce document a été validé par la Direction Technique Nationale et pour la Commission des Hauts Gradés : Frédérico Sanchis. L’ouvrage s’est inspiré de la cassette vidéo fédérale sur le Nage No Kata et des commentaires de Georges Beaudot. Il vient en complément de la planche du Nage No Kata (coopérative de documents FFJudo). Conception et réalisation - Boulogne-Billancourt - © FFJUDO Mars 2007 2 Crédit photo : D. Boulanger - Kodokan - D. Chowanek (Lines-Art) - R. Danis - DPPI. PRÉFACE Ce guide est destiné à tous les judokas, jeunes ou moins jeunes, qui souhaitent apprendre le Nage No Kata ou se perfectionner dans sa pratique. Le choix du format permettra à chacun de pouvoir le glisser facilement dans son sac de judo, et ainsi, l’avoir toujours à portée de main. Cet ouvrage, qui fait suite à la planche du Nage No Kata, vous apportera des précisions techniques et des conseils vous permettant de mieux effectuer le kata. -

Northern Virginia Ki-Aikido Instructor/Student Handbook

NORTHERN VIRGINIA KI-AIKIDO INSTRUCTOR/STUDENT HANDBOOK MEMBER DOJO OF THE EASTERN KI FEDERATION NORTHERN VIRGINIA KI-AIKIDO HEAD INSTRUCTORS STEVE WOLF SENSEI GREGORY FORD-KOHNE SENSEI EASTERN KI FEDERATION DAVID SHANER SENSEI – CHIEF INSTRUCTOR EASTERN KI FEDERATION TERRY PIERCE SENSEI – CHIEF INSTRUCTOR NEW JERSEY KI SOCIETY CHUCK AUSTER SENSEI – CHIEF INSTRUCTOR VIRGINIA KI SOCIETY February 2005 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME HOW TO GET STARTED UNIFORM CURRICULUM FOUR BASIC PRINCIPLES TO UNIFY MIND AND BODY FIVE PRINCIPLES OF SHINSHIN TOITSU AIKIDO FIVE DISCIPLINES OF SHINSHIN TOITSU AIKIDO TYPICAL ATTACKS AND THROWS DOJO ETIQUETTE TESTING NORTHERN VIRGINIA KI-AIKIDO THE EASTERN KI FEDERATION THE KI SOCIETY INTERNATIONAL PARTS OF THE BODY GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN AIKIDO APPENDICES CLASS SCHEDULE (See website, http://www.vakisociety.org/merrifield/schedule.cfm) PRACTICE FEE SCHEDULE (See website, http://www.vakisociety.org/merrifield/fees.cfm) DUES AND TESTING FEES EKF STRUCTURE and GUIDELINES SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT TO EKF WAIVER and RELEASE STUDENT PROFILE APPLICATION FOR DAN and KYU GRADES SHINSHIN TOITSU AIKIDO HITORI WAZA (AIKI TAISO) CRITERIA FOR EXAMINATION TAIGI February 2005 2 WELCOME! Northern Virginia Ki-Aikido strives to promote personal well-being and harmony in daily life for all its members through martial arts training, specifically Ki Development and Shinshin Toitsu Aikido as taught by Master Koichi Tohei, Tochigi, Japan. NVKA seeks to provide the means by which students can benefit realizing the principles of mind and body unification. HOW TO GET STARTED • Before beginning training all students must sign a Northern Virginia Ki-Aikido waiver. • Students should pay dues for the first month(s) and a one-time $25 NVKA initiation fee at the beginning of their training. -

Kids Proficiency Test

AIKIDO SHINRYUKAN CANTERBURY PROFICIENCY TEST Semi 10th &10th Kyu YELLOW WHITE TIP/YELLOW NAME: Updated Jan 14 ITEM Shikko Aiki undo [aiki exercises] * kiri ake kiri sage * fune kogi Reiho [respect, etiquette] * bowing correctly * standing correctly * tying belt Tai sabaki: * irimi: okuri ashi * irimi: tsugi ashi * ayumi ashi irimi * tenkan * irimi tenkan * tenshin [hantai tenkan] * tenkai Shomen uchi [front face strike] Katate tori [single wrist grip] Kosa dori [cross hand grip] Tai no henka: tenkan exercise Ukemi: * mai ukemi [forwards] * ushiro ukemi [backwards] Tachi waza [standing techniques] Kosa dori ikkyo omote Kosa dori ikkyo ura Katate tori shihonage omote Katate tori shihonage ura Suwari waza kokkyu ho Total Average Common errors: 1. Footwork [sabaki] 2.Hand change 3.Grabbing or catching 4.Kiiza AIKIDO SHINRYUKAN CANTERBURY PROFICIENCY TEST Semi 9th & 9th Kyu ORANGE WHITE TIP/ORANGE NAME: Updated Jan 14 ITEM Shikko Aiki undo [aiki exercises] * kiri ake kiri sage * fune kogi Reiho [respect, etiquette] * bowing correctly * standing correctly * tying belt Tai sabaki: * irimi: okuri ashi * irimi: tsugi ashi * ayumi ashi irimi * tenkan * irimi tenkan * tenshin [hantai tenkan] * tenkai Shomen uchi [front face strike] Katate tori [single wrist grip] Kosa dori [cross hand grip] Tai no henka: tenkan exercise Ukemi: Critical * mai ukemi [forwards] * ushiro ukemi [backwards] Tachi waza [standing techniques] Kosa dori ikkyo omote Kosa dori ikkyo ura Shomen uchi ikkyo omote Shomen uchi ikkyo ura Katate tori shihonage omote Katate tori shihonage -

Martial Arts from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for Other Uses, See Martial Arts (Disambiguation)

Martial arts From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses, see Martial arts (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2011) Martial arts are extensive systems of codified practices and traditions of combat, practiced for a variety of reasons, including self-defense, competition, physical health and fitness, as well as mental and spiritual development. The term martial art has become heavily associated with the fighting arts of eastern Asia, but was originally used in regard to the combat systems of Europe as early as the 1550s. An English fencing manual of 1639 used the term in reference specifically to the "Science and Art" of swordplay. The term is ultimately derived from Latin, martial arts being the "Arts of Mars," the Roman god of war.[1] Some martial arts are considered 'traditional' and tied to an ethnic, cultural or religious background, while others are modern systems developed either by a founder or an association. Contents [hide] • 1 Variation and scope ○ 1.1 By technical focus ○ 1.2 By application or intent • 2 History ○ 2.1 Historical martial arts ○ 2.2 Folk styles ○ 2.3 Modern history • 3 Testing and competition ○ 3.1 Light- and medium-contact ○ 3.2 Full-contact ○ 3.3 Martial Sport • 4 Health and fitness benefits • 5 Self-defense, military and law enforcement applications • 6 Martial arts industry • 7 See also ○ 7.1 Equipment • 8 References • 9 External links [edit] Variation and scope Martial arts may be categorized along a variety of criteria, including: • Traditional or historical arts and contemporary styles of folk wrestling vs. -

Contemporary Seniors 1: Similar but Different

Contemporary Seniors 1: Similar but Different Over 50 years of training in budo, I have been lucky enough to meet or train under many notable martial artists. This year, I want to share my impressions, some deep set, some fleeting, about the men and women I met on the way. There are several senior martial artists who I have trained with, beside, or under, albeit for a short time, separate articles about whom I have not as yet created. That is not a judgment of their worthiness or my respect for them, but that, since they are still active, I hope I can still train with or beside them. In Aiki, Miguel Ibarra and Roy Goldberg, two former partners have taken different paths, the first toward street-style ju-jutsu and aiki-ju-jutsu, the second toward a very refined and difficult aiki-no- jutsu. Both were former students of Anton Pereira. Having done seminars with them and having invited them to teach at my dojo, I can say that each represents his branch of aiki skillfully. Chronologically and in terms of time in the art, they are technically my juniors, but in their fields, their skills set a standard to which I aspire. I still reference Bruce Juchnik in a lot of the things I teach because we have found ourselves taking similar paths over the years even though he comes from a kempo and arnis background and I come from a karate and aiki background. He gets more relaxed and more effective every time I see him. If I can discover the details of a subtle movement he does—usually unconsciously—often it helps me refine some movements I am already doing consciously. -

One Circle Hold Harmless Agreement

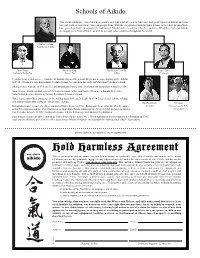

Schools of Aikido This is not a definitive list of Aikido schools/sensei, but a list of teachers who have had great impact on Aikido and who you will want to read about. You can google them. With the exception of Koichi Tohei Sensei, all teachers pictured here have passed on, but their school/style/tradition of Aikido has been continued by their students. All of these styles of Aikido are taught in the United States, as well as in many other countries throughout the world. Morihei Ueshiba Founder of Aikido Gozo Shioda Morihiro Saito Kisshomaru Ueshiba Koichi Tohei Yoshinkai/Yoshinkan Iwama Ryu Aikikai Ki Society Ueshiba Sensei (Ô-Sensei) … Founder of Aikido. Opened the school which has become known as the Aikikai in 1932. Ô-Sensei’s son, Kisshomaru Ueshiba Sensei, became kancho of the Aikikai upon Ô-Sensei’s death. Shioda Sensei was one of Ô-Sensei’s earliest students. Founded the Yoshinkai (or Yoshinkan) school in 1954. Saito Sensei was Head Instructor of Ô-Sensei’s school in the rural town of Iwama in Ibaraki Prefecture. Saito Sensei became kancho of Iwama Ryu upon Ô-Sensei’s death. Tohei Sensei was Chief Instructor of the Aikikai upon Ô-Sensei’s death. In 1974 Tohei Sensei left the Aikikai Shin-Shin Toitsu “Ki Society” and founded or Aikido. Rod Kobayashi Bill Sosa Kobayashi Sensei became the direct student of Tohei Sensei in 1961. Kobayashi Sensei was the Chief Lecturer Seidokan International Aikido of Ki Development and the Chief Instructor of Shin-Shin Toitsu Aikido for the Western USA Ki Society (under Association Koichi Tohei Sensei). -

CAA Guidelines, and All Content on the Website

California Aikido Association, LLC Guidelines California Aikido Association, LLC Guidelines (Revised and Approved by the Division Heads) March 2018) Last Update: March 2020 Table of Contents Article I: Statement of Purpose .............................................................................................................1 Article II: Membership Agreement ......................................................................................................1 A) Each member Dojo or club makes the following agreements with the Association: B) The Association makes the following agreements with its member organizations: Article III: Organizational Structure ....................................................................................................2 Article IV: Admittance Of New Members and Change of Location ...................................................2 A) Prospective Members B) Change of Location C) Transfer From Other Organizations D) Friends of the Association Article V: Annual Dues .........................................................................................................................3 Article VI: Administration ....................................................................................................................4 A) Divisions B) Executive Committee C) Guideline Review Committee D) Office of the President E) CAA Clerk/Rank Processor (RP) F) CAA Clerk/RP or Other Volunteer G) CAA Bookkeeper H) CAA Webmaster I) The CAA Website VII CAA Meetings .................................................................................................................................6 -

What Is Bigrock Aikikai?

Aikido A TRADITIONAL DISCIPLINE TO STRENGTHEN BODY, MIND & SPIRIT Instruction by What is Aikido? What is BigRock Aikikai? Bay G, 7004 – 5th Street SE Aikido is a dynamic modern Japa- BigRock Aikikai is a non-profit Sensei Steve: 403 617 6541 nese martial art, created in the 20th organization, incorporated in the www.bigrock-aikikai.com century and based on centuries of province of Alberta. Our volun- martial training. Aikido found- teer instructors have been commit- er, Morihei Ueshiba, formulated ted to teaching traditional Aikido a martial Way that merges effec- to all ages since 1998. We are lead tive technique with a mind set on by chief instructor Steve Erickson, peace. The power of an attack is 5th Dan, who has trained in Aiki- controlled and redirected not con- do since 1985. BigRock Aikikai is a fronted. The intent is not to de- member of the Alberta Aikido As- stroy an attacker but rather to ex- sociation, Canadian Aikido Feder- tinguish the violence. ation and the Aikikai Foundation (World Headquarters) in Japan. Programs Ranking Adult ranks below black belt are awarded classes without weapons Tai Jutsu by BigRock Aikikai and the Canadian Ai- Classes always begin with a light but vigor- kido Federation while black belt ranks are ous warm-up leading into drills designed awarded by Aikikai World Headquarters to work on specific skills such as tumbling in Tokyo, Japan. Students under the age of and basic body movements. Self-defense 18 progress through a colored belt ranking technique practice takes up a majority of system ranging from yellow belt through the training time and is typically done advanced black belt and if training in the with partners or in small groups. -

A Short Story of Ueshiba Morihei and His Philosophy of Life ‘Aikido’

A short story of Ueshiba Morihei And his philosophy of life ‘Aikido’ By Kim Mortensen This short essay is supposed to give the practitioner of Aikido an idea of the person behind Aikido and how Aikido was created both physically and mentally. If you have any questions or comments after reading this essay, contact me on following mail address: [email protected] ----- ,1752'8&7,21 This essay is about a man called Ueshiba Morihei, nicknamed O-sensei, and his philosophy of life; Aikido. When I first heard about Ueshiba Morihei I heard stories, which were so amazing that I thought they belonged in another age and not in this century. They were stories about a man who was able to disappear suddenly when he was attacked; something which one would expect to find in fairytales and old myths. I began to wonder who this man was and why he has been elevated into some kind of a God; there had to be an ordinary story behind the man Ueshiba Morihei. The first part of this essay will describe Ueshiba Morihei’s Biography. The second half will concern his philosophy of life, and what makes it so unique. In the biography part I will call Ueshiba Morihei by name whereas in the part on his philosophy and religion I will call him O-sensei as it was his religion and philosophy which gave him that nickname. I choose to do this because the biography part concerns a man and his achievements through his life. The second part concerns Ueshiba Morihei as a philosopher and a teacher and therefore it is more suitable to call him O-sensei in this part. -

Zenshinkan-Student-Handbook.Pdf

Zenshinkan Center for Japanese Martial, Spiritual,and Cultural Arts Student Handbook ZENSHINKAN DOJO STUDENT HANDBOOK CONTENTS The Way of Transformation .............................................................................................................. 2 Welcome to Zenshinkan Dojo ........................................................................................................... 3 Rules During Practice, Composed by the Founder ........................................................................... 5 Shugyo Policy .................................................................................................................................... 6 Basic Dojo Etiquette .......................................................................................................................... 7 Helpful Words and Phrases .............................................................................................................. 12 A History of Aikido ............................................................................................................................ 15 Zen Training ...................................................................................................................................... 17 For more information On: Our Lineage Test Requirements, Information and Applications Programs, Class Schedules and Upcoming Events Weapons Forms Techniques Zen Training Our website is a rich resource for our dojo’s current activities as well as our history. We also welcome and encourage your -

Yoshimitsu Yamada Est Né Le 1È Février 1938

Yoshimitsu Yamada est né le 1è février 1938. Il est actuellement 8è Dan Shihan. Son père est le cousin de Tadashi Abe ; c’est grâce à ce dernier que Yamada Senseï débute l’Aïkido. Uchi Deshi de Morihei Ueshiba depuis 1955 et pendant près de dix ans, Yamada Senseï se distingue par sa maîtrise de l’anglais qui le prédispose à enseigner l’Aïkido aux soldats américains. C’est tout naturellement qu’on l’envoie à New York en 1964, afin devenir professeur à l’Aïkikaï de New York. Il est reconnu pour sa pédagogie solide et claire des techniques de base. Il dirige des stages à travers le monde entier (France, Allemagne, Russie, Amérique…). Il est également à la tête de la Fédération américaine d’Aïkido, ainsi que la Fédération d’Amérique Latine. Yamada Senseï a édité de nombreux DVD pédagogiques. Beaucoup de ses élèves ont une réputation solide, et sont actuellement 7è Dan Yoshimitsu YAMADA est né le 17 février 1938 à Tokyo. Le jeune Yoshimitsu est originaire d'une famille proche de Maître UESHIBA. En effet, à la mort de ses parents, son père Ichiro YAMADA, a été adopté par la famille de Tadashi ABE, élève du fondateur. Cousins, les jeunes Ichiro et Tadashi sont élevés comme des frères. C’est à l’occasion d’une démonstration du fondateur, au sein de la famille, que le jeune Yoshimitsu découvre l’Aïkido. C’est encore un enfant mais il est déjà très attiré par la pratique du Maître. La situation préoccupante du Japon pendant la guerre, pousse les deux familles à émigrer en Corée pendant les années quarante. -

Aikido Glossary

Redlands Aikikai Glossary For a more indepth rendering of some of the terms below, please refer to the Student Handbook of the Aikido Schools of Ueshiba In general, each syllable in a Japanese word is pronounced with equal emphasis. Some syllables, though, are hardly pronounced at all (eg. Tsuki is pronounced as “tski”) Techniques The name of each technique is made up of (1) the attack, (2) the defense, and, if applicable, (3) the direction. There are four sets of directional references used in Aikido techniques (Some techniques do not have a specific “direction”): 1. Irimi (eereemee) refers to Yo (Chinese: Yang ) movement which enters through or behind the attacker and Tenkan (tehn-kahn) refers to In (Chinese: Yin ) movement which turns with the attacker’s energy. 2. Omote (ohmoeteh) refer to movements in which nage’s action is mostly in front of the attacker (also "above"), while Ura (oorah) movements take place mostly behind the attacker (also "below"). Omote and Ura also have the meanings of “exoteric” and “esoteric” (secret), respectively. 3. Uchi Mawari (oocheemahwahree) is a turn “inside” the attacker, i.e., within the compass of his arms, while Soto Mawari (sohtoemahwahree) is a turn “outside” the attacker, i.e., beyond the compass of his arms. Hence also Uchi Deshi : inside student, living in the dojo; and Soto Deshi : outside student. 4. Zenshin (zenshin), towards the front; Kotai (kohtie), towards the rear. Attacks: Japanese Word Approximate Pronunciation Approximate Meaning Eri Dori Ehree Doeree Collar Grab Gyakute Dori; Ai