The Frontier Us Army and the Transition from the War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

Trade, War and Empire: British Merchants in Cuba, 1762-17961

Nikolaus Böttcher Trade, War and Empire: British Merchants in Cuba, 1762-17961 In the late afternoon of 4 March 1762 the British war fleet left the port of Spithead near Portsmouth with the order to attack and conquer “the Havanah”, Spain’s main port in the Caribbean. The decision for the conquest was taken after the new Spanish King, Charles III, had signed the Bourbon family pact with France in the summer of 1761. George III declared war on Spain on 2 January of the following year. The initiative for the campaign against Havana had been promoted by the British Prime Minister William Pitt, the idea, however, was not new. During the “long eighteenth century” from the Glorious Revolution to the end of the Napoleonic era Great Britain was in war during 87 out of 127 years. Europe’s history stood under the sign of Britain’s aggres sion and determined struggle for hegemony. The main enemy was France, but Spain became her major ally, after the Bourbons had obtained the Spanish Crown in the War of the Spanish Succession. It was in this period, that America became an arena for the conflict between Spain, France and England for the political leadership in Europe and economic predominance in the colonial markets. In this conflict, Cuba played a decisive role due to its geographic location and commercial significance. To the Spaniards, the island was the “key of the Indies”, which served as the entry to their mainland colonies with their rich resources of precious metals and as the meeting-point for the Spanish homeward-bound fleet. -

Not for Publication United States Court of Appeals

NOT FOR PUBLICATION FILED AUG 28 2020 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS MOLLY C. DWYER, CLERK FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT U.S. COURT OF APPEALS EHM PRODUCTIONS, INC., DBA TMZ, a No. 19-55288 California corporation; WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC., a Delaware D.C. No. corporation, 2:16-cv-02001-SJO-GJS Plaintiffs-Appellees, MEMORANDUM* v. STARLINE TOURS OF HOLLYWOOD, INC., a California corporation, Defendant-Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California S. James Otero, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted August 10, 2020 Pasadena, California Before: WARDLAW and CLIFTON, Circuit Judges, and HILLMAN,** District Judge. Starline Tours of Hollywood, Inc. (Starline) appeals the district court’s * This disposition is not appropriate for publication and is not precedent except as provided by Ninth Circuit Rule 36-3. ** The Honorable Timothy Hillman, United States District Judge for the District of Massachusetts, sitting by designation. orders dismissing its First Amended Counterclaim (FACC) and denying its motion for leave to amend. We dismiss this appeal for lack of appellate jurisdiction. 1. Under 28 U.S.C. § 1291, the courts of appeals have jurisdiction over “final decisions of the district court.” Nat’l Distrib. Agency v. Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co., 117 F.3d 432, 433 (9th Cir. 1997). Generally, “a voluntary dismissal without prejudice is ordinarily not a final judgment from which the plaintiff may appeal.” Galaza v. Wolf, 954 F.3d 1267, 1270 (9th Cir. 2020) (cleaned up). A limited exception to this rule—which Starline seeks to invoke—permits an appeal “when a party that has suffered an adverse partial judgment subsequently dismisses its remaining claims without prejudice with the approval of the district court, and the record reveals no evidence of intent to manipulate our appellate jurisdiction.” James v. -

Seeking David Fagen: the Search for a Black Rebel's Florida Roots

Sunland Tribune Volume 31 Article 5 2006 Seeking David Fagen: The Search for a Black Rebel's Florida Roots Frank Schubert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune Recommended Citation Schubert, Frank (2006) "Seeking David Fagen: The Search for a Black Rebel's Florida Roots," Sunland Tribune: Vol. 31 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune/vol31/iss1/5 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sunland Tribune by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Schubert: Seeking David Fagen: The Search for a Black Rebel's Florida Roots Seeking David Fagen: The Search for a Black Re bel's Florida Roots 1 Frank Schubert Miami, Fernandina, and Jacksonville. Among them were all four regiments of black regu avid Fagen was by far the best lars: three (the 9th Cavalry, and the 24th known of the twenty or so black and 25th Infantry regiments) in Tampa, and soldiers who deserted the U.S. a fourth, the 10th Cavalry, in Lakeland. Re DArmy in the Philippines at the cently the experience of these soldiers in turn of the twentieth century and went the Florida has been the subject of a growing next step and defected to the enemy. I !is number of books, articles, and dissertations.2 story fi lled newspapers great and small , Some Floridians joined regular units, from the New Yori? 11imes to the Crawford, and David Fagen was one of those. -

Fort Funston, Panama Mounts for 155Mm Golden Gate National

Fort Funston, Panama Mounts for 155mm Guns HAERNo. CA-193-A B8'•'■ANffiA. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Skyline Boulevard and Great Highway San Francisco San Francisco County California PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Department of the Interior San Francisco, California 38 ) HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD • FORT FUNSTON, PANAMA MOUNTS FOR 155mm GUNS HAERNo.CA-193-A Location: Fort Funston, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, City and County of San Francisco, California Fort Funston is located between Skyline Boulevard and the Pacific Ocean, west of Lake Merced. The Battery Bluff Panama mounts were located at Fort Funston, 1,200 feet north of Battery Davis' gun No. 1, close to the edge of the cliff overlooking the beach Date of Construction: 1937 Engineer: United States Army Corps of Engineers Builder: United States Army Corps of Engineers Present Owner: United States National Park Service Golden Gate National Recreation Area Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94123 Present Use: Not Currently Used Due to erosion, Battery Bluff Panama mounts have slipped to the beach below where they are still visible Significance: The Panama mounts of Battery Bluff are significant as they are a contributing feature to the Fort Funston Historic District which is considered eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. The Panama mounts were the only guns of its type to be emplaced in the San Francisco Harbor Defenses. Report Prepared By: Darlene Keyer Carey & Co. Inc., Historic Preservation Architects 123 Townsend Street, Suite 400 San Francisco, CA 94107 Date: February 26, 1998 r FORT FUNSTON, PANAMA MOUNTS FOR 155mm GUNS HAERNO.CA-193-A PAGE 2 HISTORY OF FORT FUNSTON Fort Funston Historic District Fort Funston, which is located in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 and is now considered the Fort Funston Historic District. -

COL. Theodore Roosevelt, the Rough Riders & Camp Wikoff

Transcript of Lecture Delivered by Jeff Heatley on Friday September 18, 1998 COL. Theodore Roosevelt, The Rough Riders & Camp Wikoff On August 7th, 1898, the transport Miami, with Gen. Joseph Wheeler, Col. Theodore Roosevelt, the Rough Riders and members of the Third Cavalry on board, pulled away from the dock at Santiago, Cuba to begin its voyage north. Anxious that his men not miss the sights, Col. Roosevelt urged them to stay on deck. As the ship approached Morro Castle, the Third Cavalry band began to play John Howard Payne's "Home, Sweet Home". The American soldiers stationed at the castle cheered wildly as the homeward-bound troops passed by. The Gate City, the first transport to start north, had left Santiago two days earlier. Over the next five weeks, nearly forty ships would bring a total of 22,500 soldiers of Gen. Shafter's Fifth Army Corps from Santiago de Cuba to Montauk, where a 4,200-acre military encampment had been hastily prepared for their rest and recuperation. The 2,000-mile, eight-day journey would prove a further test for the heroes of the Spanish-American War. Many suffered the ill effects of tropical diseases like malaria, typhoid, dysentery and, in a few cases, yellow fever. The ships were over-crowded and lacked adequate supplies for healthy men, let alone fever-stricken ones. Both the Mobile and Allegheny transports were called "death ships" on arrival at Fort Pond Bay. Thirteen soldiers had died on board the Mobile and been buried at sea; fourteen on the Allegheny suffered the same fate. -

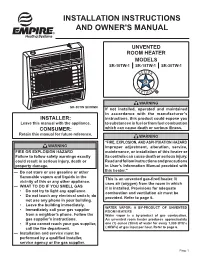

Installation INSTRUCTIONS and OWNER's MANUAL

Installation INSTRUCTIONS AND OWNER'S MANUAL UNVENTED ROOM HEATER MODELS SR-10TW-1 SR-18TW-1 SR-30TW-1 WARNING SR-30TW SHOWN If not installed, operated and maintained in accordance with the manufacturer’s INSTALLER: instructions, this product could expose you Leave this manual with the appliance. to substances in fuel or from fuel combustion CONSUMER: which can cause death or serious illness. Retain this manual for future reference. WARNING “FIRE, EXPLOSION, AND ASPHYXIATION HAZARD WARNING Improper adjustment, alteration, service, FIRE OR EXPLOSION HAZARD maintenance, or installation of this heater or Failure to follow safety warnings exactly its controls can cause death or serious injury. could result in serious injury, death or Read and follow instructions and precautions property damage. in User’s Information Manual provided with — Do not store or use gasoline or other this heater.” flammable vapors and liquids in the This is an unvented gas-fired heater. It vicinity of this or any other appliance. uses air (oxygen) from the room in which — WHAT TO DO IF YOU SMELL GAS it is installed. Provisions for adequate • Do not try to light any appliance. combustion and ventilation air must be • Do not touch any electrical switch; do provided. Refer to page 6. not use any phone in your building. • Leave the building immediately. WATER VAPOR: A BY-PRODUCT OF UNVENTED • Immediately call your gas supplier ROOM HEATERS from a neighbor’s phone. Follow the Water vapor is a by-product of gas combustion. gas supplier’s instructions. An unvented room heater produces approximately • If you cannot reach your gas supplier, one (1) ounce (30ml) of water for every 1,000 BTU’s call the fire department. -

Fioney Relting Has Not 7 Tar- ,Nessful Tn Yet Decided1 Rank Commensurate with the Importance 1Artllat.ES

SPECIAL NOTICES. RUSSIA AND CHINA MADE MAJOR GENERAL FINANCIAL. FINANCLAId. Cash.- ash for r stock of frnialhing.. shoves. clething. etc. jy19-4tf SALI BEHREND, Frednia Hotel. Garden Ft. A Declaration of War by the Former Ohafee's Rank to Be ommnnmin Very Reckless Hose, 6%c. per An Irislhman, ee one ltetto, grade at higher prices. We are Dot coo- the of who had been Saturday, July 21, fne.l to, any particular brand. but buy the beat In Would Alter Conditions. With Me Comman hanged. having been asked how his father died. -Li THE- the n.rk.-t for the muhoey. Give us a trial. Ii 4b tha eluded admitting the fact: "BSore. thin. my l14 1,112F & CO., Ruiser toods, 511 9th at. n.w. father, who was a very reckless man. was Jst j.1*-7St.6 atandin' on a platform barasgaing a mob. when a LAST DAY in a New Front OUR TROOPS WOULD BE WITHDRAWI part of the platform suddenly gave way, and he to secure stock in this Put SATITACTIOI AT TE BLC fell and thin it was hi neck company It will Inre..se your business this fall- through, found that -AT give Yem a tter Ir.d..w show. etc. This was broken. ba _air busines. Estiuates and plans fur- 'Iat was reckless of him, but It is altmost as recklem $6.00 GEl6. W. V RIIET, 5'.l 10th t. 'Phone 17A6-3. of How the Provisions of the Law muy4-3t-7 Appointment Special Diplomatic Fully worth par. which is $1o per When youwant acarpenter Agent Discussed. -

THE ARIZONA ROUGH RIDERS by Harlan C. Herner a Thesis

The Arizona rough riders Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Herner, Charles Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 02:07:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551769 THE ARIZONA ROUGH RIDERS b y Harlan C. Herner A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1965 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of require ments for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under the rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of this material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: MsA* J'73^, APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: G > Harwood P. -

Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines

Title: Comparison of Spanish Colonization—Latin America and the Philippines Teacher: Anne Sharkey, Huntley High School Summary: This lesson took part as a comparison of the different aspects of the Spanish maritime empires with a comparison of Spanish colonization of Mexico & Cuba to that of the Philippines. The lessons in this unit begin with a basic understanding of each land based empire of the time period 1450-1750 (Russia, Ottomans, China) and then with a movement to the maritime transoceanic empires (Spain, Portugal, France, Britain). This lesson will come after the students already have been introduced to the Spanish colonial empire and the Spanish trade systems through the Atlantic and Pacific. Through this lesson the students will gain an understanding of Spanish systems of colonial rule and control of the peoples and the territories. The evaluation of causes of actions of the Spanish, reactions to native populations, and consequences of Spanish involvement will be discussed with the direct correlation between the social systems and structures created, the influence of the Christian missionaries, the rebellions and conflicts with native populations between the two locations in the Latin American Spanish colonies and the Philippines. Level: High School Content Area: AP World History, World History, Global Studies Duration: Lesson Objectives: Students will be able to: Compare the economic, political, social, and cultural structures of the Spanish involvement in Latin America with the Spanish involvement with the Philippines Compare the effects of mercantilism on Latin America and the Philippines Evaluate the role of the encomienda and hacienda system on both regions Evaluate the influence of the silver trade on the economies of both regions Analyze the creation of a colonial society through the development of social classes—Peninsulares, creoles, mestizos, mulattos, etc. -

Race and Inequality in Cuban Tourism During the 21St Century

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2015 Race and Inequality in Cuban Tourism During the 21st Century Arah M. Parker California State University - San Bernardino Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Tourism Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Arah M., "Race and Inequality in Cuban Tourism During the 21st Century" (2015). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 194. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/194 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE AND INEQUALITY IN CUBAN TOURISM DURING THE 21 ST CENTURY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences by Arah Marie Parker June 2015 RACE AND INEQUALITY IN CUBAN TOURISM DURING THE 21 ST CENTURY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Arah Marie Parker June 2015 Approved by: Dr. Teresa Velasquez, Committee Chair, Anthropology Dr. James Fenelon, Committee Member Dr. Cherstin Lyon, Committee Member © 2015 Arah Marie Parker ABSTRACT As the largest island in the Caribbean, Cuba boasts beautiful scenery, as well as a rich and diverse culture. -

Spanish American War 8/6/11 1:19 PM Page Iii

DM - Spanish American War 8/6/11 1:19 PM Page iii Defining Moments The spanish- American War Kevin Hillstrom and Laurie Collier Hillstrom 155 W. Congress, Suite 200 Detroit, MI 48226 DM - Spanish American War 8/6/11 1:19 PM Page v Table of Contents Preface . .ix How to Use This Book . .xiii Research Topics for Defining Moments: The Spanish-American War . .xv NARRATIVE OVERVIEW Prologue . .3 Chapter One: American Expansion in the 1800s . .7 Chapter Two: Spain and Its Colonies . .23 Chapter Three: The Call to Arms: Remember the Maine! . .35 Chapter Four: A “Splendid Little War” in Cuba . .53 Chapter Five: The War in the Philippines . .71 Chapter Six: American Imperialism in the New Century . .85 Chapter Seven: Legacy of the Spanish-American War . .103 BIOGRAPHIES Emilio Aguinaldo (1869-1964) . .121 Filipino Rebel Leader and Politician George Dewey (1837-1917) . .124 American Naval Commander of U.S. forces in the Pacific during the Spanish-American War William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951) . .128 American Newspaper Publisher of the New York Journal and Leading Architect of “Yellow Journalism” v DM - Spanish American War 8/6/11 1:19 PM Page vi Defining Moments: The Spanish-American War Queen Lili’uokalani (1838-1917) . .132 Last Monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaii Antonio Maceo (1845-1896) . .136 Cuban Military Leader in the Ten Years’ War and the Spanish-American War José Martí (1853-1895) . .140 Cuban Revolutionary Leader and Writer William McKinley (1843-1901) . .143 President of the United States during the Spanish-American War Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) . .147 Hero of the Spanish-American War and President of the United States, 1901-1909 Valeriano Weyler (1838-1930) .