Flower Closure Enhances Pollen Viability in Crocus Discolor G. Reuss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plants That Bite Back. Carolina Beach State Park: an Environmental Education Learning Experience Designed for the Middle Grades

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 376 026 SE 054 367 AUTHOR Wahab, Phoebe TITLE Plants that Bite Back. Carolina Beach State Park: An Environmental Education Learning Experience Designed for the Middle Grades. INSTITUTION North Carolina State Dept. of Environment, Health, and Natural Resources, Raleigh. Div. of Parks and Recreation. PUB DATE 93 ::OTE 131p.; For other Environmental Education Learning Experiences, see SE 054 364-371. AVAILABLE FROMNorth Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation, P.O. Box 27687, Raleigh, NC 27611-7687. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Botany; Conservation (Environment); *Endangered Species; *Environmental Education; Experiential Learning; Field Trips; Intermediate Grades; Junior High Schools; Middle Schools; Natural Resources; Outdoor Activities; *Outdoor Education; Plant Growth; Plants (Botany); Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS *Biological Adaptations; *Carnivorous Plants; Natural Resources Management; Nature; North Carolina; State Parks ABSTRACT This learning packet, one in a series of eight, was developed by the Carolina Beach State Park in North Carolina for the middle grades to teach about carnivorous plants. Loose-leaf pages are presented in 10 sections that contain:(1) introductions to the North Carolina State Park System, the Carolina Beach State Park, the park's activity packet, and how plants eat;(2) a summary of the activities that includes major concepts and objectives covered; (3) four pre-visit activities on carnivorous plants;(4) three -

ORCHIDS Lincoln Park Conservatory and Gardens Docent Training March 14, 2020

ORCHIDS Lincoln Park Conservatory and Gardens Docent Training March 14, 2020 Contents Title Page 1. Essential Orchids 1 2. Essential Carnivorous Plants 4 3. Orchid Room Highlights 6 4. History of Orchids 8 5. Orchids and their Pollinators 11 6. Orchids 17 7. What are Bromeliads 21 8. Bromeliads 24 9. Epiphytic Cacti 25 10. Tropical Cacti 27 11. Carnivorous Plants 29 12. Carnivorous Plants 2 33 13. Ant Plants 35 14. Ant Plants 2 37 15. Vanilla Orchid 36 16. Goldfish vs. Koi 39 Reading assignments supplement each week’s lectures. Please read before the lecture. This page intentionally left blank Essential Orchids Orchids are one of the oldest and largest families in the plant kingdom with over 25,000 species worldwide. Through the millions of years of their existence, they developed complex relationships with their pollinators, animal communities, and environment in general. Today, orchids are now among the most widely grown and popular flowering potted plants in the world. With modern scientific cultivation, there are over 100,000 varieties of orchids and the number is increasing. However, in the wild populations are declining; many orchids are on the endangered lists, and almost all collecting of orchids is banned. What Makes an Orchid an Orchid? All orchids share three basic characteristics: ● Three sepals ● Three petals. In most orchids, one of these is highly modified and called a lip, or labellum. These are easy to see in most of the common orchids, and act as a landing pad for insect pollinators. ● A column. In most flowers the male (stamen) and female (pistil) reproductive structures are separate. -

Chemical Reactions and Equations 01

Chapter Chemical Reactions 01 and Equations WORKSHEET - 1 Introduction to Chemical Reactions I. 1. b) 2. a) 3. a) 4. a) 5. c) II. 1. exothermic 2. iron oxide 3. reactants 4. precipitate 5. hydrogen gas III. 1. 2NH3 + 3CuO 3Cu + N2 + 3H2O 2. Al2(SO4)3 + 6NaOH 2Al(OH)3 + 3Na2SO4 3. 4Fe + 3O2 2Fe2O3 4. 2NaOH + H2SO4 Na2SO4 + 2H2O 5. MnO2 + 4HCl MnCl2 + Cl2 + 2H2O I V. 1. It is because sunlight is absorbed in this process. 2. a) Precipitate formation b) Evolution of gas 3. a) Hydrogen gas is evolved. b) It is an exothermic reaction. 4. a) Reaction of iron with copper sulphate: Fe + CuSO4 FeSO4 + Cu (Blue) (Green) b) Reaction of quicklime with water: CaO + H2O Ca(OH)2 + Heat V. 1. • By writing the state symbols of each component. • By indicating evolution of gas (↑) or precipitate formation (↓). • By writing the number of molecules of each component in a balanced equation. • By indicating colour change. • By indicating the release or absorption of heat. 2. a) BaCl2(aq) + Na2SO4(aq) BaSO4(s) + 2NaCl(aq) b) 2Fe + 3H2O(g) Fe2O3(s) + 3H2(g) 3. a) Large amount of heat is released. b) The gas evolved (CO2) turns lime water milky. c) The solution will change colour from purple to colourless. TM A DDITION LA PR CTICEA SCIENCE-10 1 WORKSHEET - 2 Types of Chemical Reactions I. 1. Decomposition reaction 2. Catalyst 3. Platinum 4. Potassium 5. Slaked lime II. 1. Yes 2. No 3. Yes 4. Yes 5. No III. 1. CO2 2. Fe 2O3 3. Cl2 4. -

Mechanism for Rapid Passive-Dynamic Prey Capture in a Pitcher Plant

Bauer, U. , Paulin, M., Robert, D., & Sutton, G. P. (2015). Mechanism for rapid passive-dynamic prey capture in a pitcher plant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(43), 11384-11389. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1510060112 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1073/pnas.1510060112 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES: Plant Biology Mechanism for rapid passive-dynamic prey capture in a pitcher plant Short title: Passive-dynamic pitcher plant trap Ulrike Bauer a,b , Marion Paulin c, Daniel Robert a, Gregory P. Sutton a aSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, 24 Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TQ, UK bDepartment of Biology, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Tungku Link, Gadong 1410, Brunei Darussalam cÉcole Nationale Supérieure d’Agronomie de Toulouse, Avenue de l’Agrobiopole, B.P. 32607 Auzeville-Tolosane, 31326 Castanet-Tolosan Cédex Corresponding author: Ulrike Bauer School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, 24 Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TQ, UK phone: +44 117 39 41296 email: [email protected] keywords: Carnivorous plants, biomechanics, trapping mechanism, torsion spring, wax crystals Abstract Plants use rapid movements to disperse seed, spores or pollen, and catch animal prey. Most rapid release mechanisms only work once, and if repeatable, regaining the pre-release state is a slow and costly process. -

How Plants Move

florolo gy 101 By Kirk Pamper AIFD, AAF, PFCI “fangs,” the Venus flytrap has the sinister look of a How plants can be— creature from science fiction, which probably and have—a “moving accounts for its notoriety…well, that and the fact that it eats bugs alive. experience.” While the Venus flytrap may be the most dramatic example of movement in plants, there are several other ways in which plants display kinetic energy, Most of us tend to think of plants as stationary from the subtle to the startling. beings. Yes, they grow and flower and reproduce, even photosynthesize—it’s not as if they aren’t doing anything—but in general, plants don’t display A good turn the kind of movement that can be observed by the naked eye, or that could even be documented hour Rooted in one place, lacking eyes or ears or legs to by hour. It’s been said that movement is what find their way to food and water, plants have had to distinguishes plants from animals. develop other ways of satisfying their needs. Most plant movements are subtle; they occur gradually over But many kinds of plants do move, and even some a period of minutes or hours. Consider, for starters, the cut flowers seem to defy our notion of what a plant tropisms, which are various types of plant movement is: namely, something that sits still. Perhaps in response to environmental stimuli. foremost among these is the infamous Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) . With its hair-trigger “jaws” and Phototropism, the directional movement of a plant its lurid red “throat” lined with fierce-looking in response to light, helps guide the growing plant toward a source of energy it needs for photosynthesizing. -

10 Top 10 Fascinating Carnivorous Plants

9/15/2015 Top 10 Fascinating Carnivorous Plants Listverse PREVIOUS NEXT OUR WORLD Top 10 Fascinating Carnivorous Plants CHRISTINE VREY JUNE 9, 2011 Out of all the strange plants in the world, who would have thought that you even get flesh eating plants? Well, maybe not so much “flesh” eating, as insect eating, but carnivorous none the less. All carnivorous plants can be found in areas where the soil has very little nutrients. These fascinating plants are categorized as carnivorous as they trap insects and arthropods, produce digestive juices, dissolve the prey and derive some, or most, of their nutrients from this process. The first book on these plants was written by Charles Darwin, in 1875, “Insectivorous Plants”. After further discoveries and research, it is believed that these carnivorous properties evolved on six separate occasions, from five different orders of flowering plants. These are now presented in over 630 different species of flowering plant. There are five basic trapping mechanisms found in all these plants: Pitfall traps, Fly Paper traps, Snap traps, Bladder traps and Lobster pot traps. I would like to show you a couple of plants, using each mechanism, so that you can also see the differences between different genera. Sarracenia 10 http://listverse.com/2011/06/09/top10fascinatingcarnivorousplants/ 1/19 9/15/2015 Top 10 Fascinating Carnivorous Plants Listverse Sarracenia, or the North American Pitcher plant, is a Genus of carnivorous plants indigenous to the eastern seaboard, Texas, the great lakes and south eastern Canada, with most species being found only in the southeast states. -

7Th Proceeding of the Plant Biomechanics International Conference Bruno Moulia, Meriem Fournier

7th Proceeding of the Plant Biomechanics International Conference Bruno Moulia, Meriem Fournier To cite this version: Bruno Moulia, Meriem Fournier. 7th Proceeding of the Plant Biomechanics International Conference. 7th Plant Biomechanics International Conference, Aug 2012, Clermont-Fd, France. INRA, 394 p., 2012, 2105-1089. hal-01195122 HAL Id: hal-01195122 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01195122 Submitted on 30 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Table of Contents 7th Plant Biomechanics International Conference – Clermont-Ferrand – August 2012 2 7th Plant Biomechanics International Conference – Clermont-Ferrand – August 2012 Program.........................................................................................................................................................................................9 What is Plant Biomechanics? Bruno MOULIA & Meriem FOURNIER................................................................................29 Sessions........................................................................................................................................................................................33 -

Mechanism for Rapid Passive-Dynamic Prey Capture in a Pitcher Plant

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Explore Bristol Research Bauer, U., Paulin, M., Robert, D., & Sutton, G. P. (2015). Mechanism for rapid passive-dynamic prey capture in a pitcher plant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(43), 11384-11389. 10.1073/pnas.1510060112 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1073/pnas.1510060112 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/pure/about/ebr-terms.html Take down policy Explore Bristol Research is a digital archive and the intention is that deposited content should not be removed. However, if you believe that this version of the work breaches copyright law please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: • Your contact details • Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL • An outline of the nature of the complaint On receipt of your message the Open Access Team will immediately investigate your claim, make an initial judgement of the validity of the claim and, where appropriate, withdraw the item in question from public view. BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES: Plant Biology Mechanism for rapid passive-dynamic prey capture in a pitcher plant Short title: Passive-dynamic pitcher plant trap Ulrike Bauer a,b , Marion Paulin c, Daniel Robert a, Gregory P. -

Biomedia for Entertainment

BioMedia for Entertainment Ben Salem1,*, Adrian Cheok2, and Adria Bassaganyes3 1,3 Department of Industrial Design, Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands 2 Mixed Reality Lab, National University of Singapore, Singapore [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], www.bsalem.info Abstract. In this paper we report on a novel form of media we call BioMedia. We introduce the concept and we explain its features. We then present two prototypes we have developed using BioMedia in entertainment. Keywords: BioMedia, Multimedia, Empathy, Entertainment. 1 Introduction BioMedia is a new media form that uses some property of living beings, in particular plants, as the medium for communication. Rather than use conventional media, say music, to render some information, BioMedia relies on health, shape, pigmentation or bioluminescence of living organism. We would like to introduce the concept of BioMedia with our implementation of two entertaining systems. We focus on plants, in fact houseplants, as they have interesting features. Houseplants require continuous attention. Regular watering and soil checks are necessary for a houseplant to thrive and be healthy. Houseplants trigger empathy from their owner as s/he feel a duty to care for the plant. Plants can trigger emotions that go beyond what inanimate possessions can trigger. There are anecdotal evidences, when inquiring about ownership of houseplants, of an emotional and empathy link between owners and plants. Houseplant form part of a house environment atmosphere and have a role in the overall perception one has of a room. We believe an entertainment value can be added if the plant is the embodiment of some information semantically coupled with users of that room. -

Botanical Record-Breakers Wayne's Word Index Noteworthy Plants Trivia Lemnaceae Biology 101 Botany Search Botanical Record-Breakers

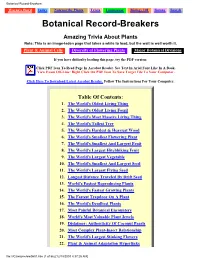

Botanical Record-Breakers Wayne's Word Index Noteworthy Plants Trivia Lemnaceae Biology 101 Botany Search Botanical Record-Breakers Amazing Trivia About Plants Note: This is an image-laden page that takes a while to load, but the wait is well worth it. Plant & Animal Cells Diversity of Flowering Plants Major Botanical Divisions If you have difficulty loading this page, try the PDF version: Click PDF Icon To Read Page In Acrobat Reader. See Text In Arial Font Like In A Book. View Exam Off-Line: Right Click On PDF Icon To Save Target File To Your Computer. Click Here To Download Latest Acrobat Reader. Follow The Instructions For Your Computer. Table Of Contents: 1. The World's Oldest Living Thing 2. The World's Oldest Living Fossil 3. The World's Most Massive Living Thing 4. The World's Tallest Tree 5. The World's Hardest & Heaviest Wood 6. The World's Smallest Flowering Plant 7. The World's Smallest And Largest Fruit 8. The World's Largest Hitchhiking Fruit 9. The World's Largest Vegetable 10. The World's Smallest And Largest Seed 11. The World's Largest Flying Seed 12. Longest Distance Traveled By Drift Seed 13. World's Fastest Reproducing Plants 14. The World's Fastest Growing Plants 15. The Fastest Trapdoor On A Plant 16. The World's Deadliest Plants 17. Most Painful Botanical Encounters 18. World's Most Valuable Plant Jewels 19. Dislaimer: Authenticity Of Coconut Pearls 20. Most Complex Plant-Insect Relationship 21. The World's Largest Stinking Flowers 22. Plant & Animal Adaptation Hyperlinks file:///C|/wayne/ww0601.htm (1 of 56) [12/19/2003 8:37:28 AM] Botanical Record-Breakers 23. -

The Unique Plant: Mimosa Plant

The Unique Plant: Mimosa Plant Mimosa is a genus of about 400 species of herbs and shrubs, in the subfamily Mimosoideae of the legume family Fabaceae. There are two species in the genus that are notable. One is Mimosa pudica, because of the way it folds its leaves when touched or exposed to heat. It is native to southern Central and South America but is widely cultivated elsewhere for its curiosity value, both as a houseplant in temperate areas, and outdoors in the tropics. Outdoor cultivation has led to weedy invasion in some areas, notably Hawaii. The other is Mimosa tenuiflora, which is best known for its use in shamanic ayahuasca brews due to the psychedelic drug dimethyltryptamine found in its root bark. Mimosa pudica Mimosa pudica (from Latin: pudica "shy, bashful or shrinking"; also called sensitive plant, sleepy plant and the touch-me-not), is a creeping annual or perennial herb, the compound leaves fold inward and droop when touched or shaken, to protect them from predators, re- opening minutes later. The species is native to South America and Central America, but is now a pantropical weed. It grows mostly in shady areas, under trees or shrubs. The stem is erect in young plants, but becomes creeping or trailing with age. It can hang very low and become floppy. The stem is slender, branching, and sparsely to densely prickly, growing to a length of 1.5 m (5 ft). The leaves of the mimosa pudica are compound leaves. The leaves are bipinnately compound, with one or two pinnae pairs, and 10–26 leaflets per pinna. -

The Plant Kingdom's Most Unusual Talents

The Plant Kingdom's Most Unusual Talents Plants do not just laze about, soaking up rays. They shift around, hunt, eat, attack--and defend themselves Wikim Plants seem so passive. Tree branches bow to the wind, losing their leaves. Lettuce just sits there as snails help themselves to a free salad bar. And grass lets everyone walk all over it. But all that apparent listlessness is deceptive. In truth, plants are incredibly active members of their communities. Plants move on their own all the time—creeping, digging, reaching, blooming. However, most of the action happens too slowly for our eyes to see unaided. In his 1995 documentary series The Private Life of Plants, David Attenborough and his crew created beautiful time-lapse videos to showcase plants' hidden mobility. Climbing jungle vines race one another up tree trunks, stretching towards the sunlight. The thorny bramble whips from side to side, shoving competing plants out of the way to expand its territory. A spindly orange vine known as dodder is a particularly striking example of dynamic plant life. Dodder is a parasite—it lives off of other plants. Instead of waiting around for a suitable host, the vine hunts one down.Conseulo De Moraes of Penn State University planted a young dodder near a tomato plant and continuously filmed the pair for several days. Her time-lapse video reveals a growing dodder flailing around, tasting the air like a snake, until it finally brushes the tomato's stem and begins to encircle its victim. Eventually it would sink tiny nozzles into the tomato plant to suck out vital juices.