Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tributes1.Pdf

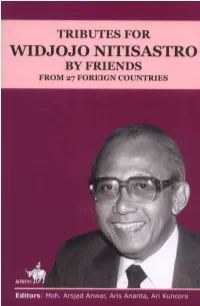

Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, January 2007 Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Published by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, January 2007 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70007006 Editor: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editor: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. -

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: a Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: John O. Haley, Chair Michael E. Townsend Beth E. Rivin Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Law © Copyright 2015 Yu Un Oppusunggu ii University of Washington Abstract Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor John O. Haley School of Law A sweeping proviso that protects basic or fundamental interests of a legal system is known in various names – ordre public, public policy, public order, government’s interest or Vorbehaltklausel. This study focuses on the concept of Indonesian public order in private international law. It argues that Indonesia has extraordinary layers of pluralism with respect to its people, statehood and law. Indonesian history is filled with the pursuit of nationhood while protecting diversity. The legal system has been the unifying instrument for the nation. However the selected cases on public order show that the legal system still lacks in coherence. Indonesian courts have treated public order argument inconsistently. A prima facie observation may find Indonesian public order unintelligible, and the courts have gained notoriety for it. This study proposes a different perspective. It sees public order in light of Indonesia’s legal pluralism and the stages of legal development. -

Governing the International Commercial Contract Law: the Framework of Implementation to Establish the ASEAN Economy Community 2015

Governing the International Commercial Contract Law: The Framework of Implementation to Establish the ASEAN Economy Community 2015 Taufiqurrahman, University of Wijaya Putra, Indonesia Budi Endarto, University of Wijaya Putra, Indonesia The Asian Conference on Business and Public Policy 2015 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract The Head of the State Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in Summit of Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2007 on Cebu, Manila agreed to accelerate the implementation of ASEAN Economy Community (AEC), which was originally 2020 to 2015. This means that within the next seven months, the people of Indonesia and ASEAN member countries more integrated into one large house named AEC. This in turn will further encourage increased volume of international trade, both by the domestic consumers to foreign businesses, among foreign consumers by domestic businesses, as well as between foreign entrepreneurs with domestic businesses. As a result, the potential for legal disputes between the parties in international trade transactions can not be avoided. Therefore, the existence of the contract law of international commercial law in order to provide maximum protection for the parties to a transaction are indispensable. The existence of this legal regime will provide great benefit to all parties to a transaction to minimize disputes. This study aims to assess the significance of the governing of International Commercial Contract Law for Indonesia in the framework of the implementation of establishing the AEC 2015 and also to find legal principles underlying governing the International Commercial Contracts Law for Indonesia in the framework of the implementation of establishing the AEC 2015 so as to provide a valuable contribution to the development of Indonesian national law. -

Living Adat Law, Indigenous Peoples and the State Law: a Complex Map of Legal Pluralism in Indonesia Mirza Satria Buana

Living adat Law, Indigenous Peoples and the State Law: A Complex Map of Legal Pluralism in Indonesia Mirza Satria Buana Biodata: A lecturer at Lambung Mangkurat University, South Kalimantan, Indonesia and is currently pursuing a Ph.D in Law at T.C Beirne, School of Law, The University of Queensland, Australia. The author’s profile can be viewed at: http://www.law.uq.edu.au/rhd-student- profiles. Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper examines legal pluralism’s discourse in Indonesia which experiences challenges from within. The strong influence of civil law tradition may hinder the reconciliation processes between the Indonesian living law, namely adat law, and the State legal system which is characterised by the strong legal positivist (formalist). The State law fiercely embraces the spirit of unification, discretion-limiting in legal reasoning and strictly moral-rule dichotomies. The first part of this paper aims to reveal the appropriate terminologies in legal pluralism discourse in the context of Indonesian legal system. The second part of this paper will trace the historical and dialectical development of Indonesian legal pluralism, by discussing the position taken by several scholars from diverse legal paradigms. This paper will demonstrate that philosophical reform by shifting from legalism and developmentalism to legal pluralism is pivotal to widen the space for justice for the people, particularly those considered to be indigenous peoples. This paper, however, only contains theoretical discourse which was part of pre-liminary -

Law Reform in Post-Sukarno Indonesia

JUNE S. KATZ AND RONALD S. KATZ* Law Reform in Post-Sukarno Indonesia Sukarno, Indonesia's president for two decades,' did not give a very high priority to law reform, as indicated by his statement to a group of lawyers in 1961 that "one cannot make a revolution with lawyers." 2 Since his fall from power, however, there have been many efforts to bring Indonesia closer to its goal of becoming a "Negara Hukum" (state based on the rule of law). 3 The purpose of this article is to describe the systematic progress that has been made in this direction. Perhaps the best way to chart this progress is to trace the career of an Indonesian leader, Professor Dr. Mochtar Kusumaatmadja, who has been very active in the law reform area. His career may be viewed in three stages, which parallel the recent stages of law reform in Indonesia.4 During the first stage-the latter part of the Sukarno regime-Professor Mochtar had to live outside of Indonesia because his view of law differed sharply from that of Sukarno. I In the second stage-the early years of the Suharto government when law reform activity centered in the law schools-Professor Mochtar was dean of the state law school *Both authors received the J.D. degree from Harvard Law School in 1972. During the preparation of this article, they were working on a grant from the International Legal Center, New York. '1945 through approximately 1965. 'Speech to Persahi (Law Association) Congress, Jogiakarta, 1961, as reported to HUKUM DAN MASJARAKAT (JOURNAL OF LAW AND SOCIETY), NOMOR KONGRES 1, 1961, p. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraoh numbers Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 - 1.10 Chapter 2 The 1891 Boundary Convention Did Not Affect the Disputed Islands The Territorial Title Alleged by Indonesia Background to the Boundary Convention of 20 June 189 1 The Negotiations for the 189 1 Convention The Survey by HMS Egeria, HMS Rattler and HNLMS Banda, 30 May - 19 June 1891 The Interpretation of the 189 1 Boundary Convention The Ratification of the Boundary Convention and the Map The Subsequent 19 15 Agreement General Conclusions Chapter 3 Malaysia's Right to the Islands Based on Actual Administration Combined with a Treaty Title A. Introduction 3.1 - 3.4 B. The East Coast Islands of Borneo, Sulu and Spain 3.5 - 3.16 C. Transactions between Britain (on behalf of North Borneo) and the United States 3.17 - 3.28 D. Conclusion 3.29 Chapter 4 The Practice of the Parties and their Predecessors Confirms Malaysia's Title A. Introduction B. Practice Relating to the Islands before 1963 C. Post-colonial Practice D. General Conclusions Chapter 5 Officia1 and other Maps Support Malaysia's Title to the Islands A. Introduction 5.1 - 5.3 B. Indonesia's Arguments Based on Various Maps 5.4 - 5.30 C. The Relevance of Maps in Determining Disputed Boundaries 5.31 - 5.36 D. Conclusions from the Map Evidence as a Whole 5.37 - 5.39 Submissions List of Annexes Appendix 1 The Regional History of Northeast Bomeo in the Nineteenth Century (with special reference to Bulungan) by Prof. Dr. Vincent J. H. Houben Table of Inserts Insert Descri~tion page 1. -

Editorial Khazanah

KhazEditanahorial Mochtar Kusumaatmadja Prof. Mochtar Kusumaatmadja adalah salah satu tokoh yang menempa posisi khusus dalam perkembangan pemikiran hukum dan pendidikan nggi hukum di Indonesia. Kekhususan posisi ini terletak pada komplitnya sosok Mochtar yang bukan saja sebagai pendidik, tapi juga pemikir, praksi, dan juga birokrat hukum. Sebagai pendidik, Mochtar adalah figur penng dibalik reformasi pendidikan nggi hukum di Indonesia pada awal tahun 1970-an dengan menjadikan Fakultas Hukum Universitas Padjadjaran (Unpad) yang dipimpinnya sebagai laboratoriumnya.¹ Sarjana hukum pasca kemerdekaan menurut Mochtar harus menjadi seorang “professional lawyer” atau teknokrat hukum yang mendampingi para teknokrat lainnya dalam membangun Indonesia.² Untuk mewujudkan gagasan ini Mochtar kemudian memprakarsai program pendidikan klinis hukum di Fakultas Hukum Unpad sebagai proyek percontohan (pilot project). Mochtar adalah salah satu tokoh pemikir hukum Indonesia garda depan. Gagasannya mengenai peran hukum dalam pembangunan mendapat momentum yang tepat untuk diaplikasikan keka ia menjabat sebagai Menteri Kahakiman (birokrat hukum) pada tahun 1974. Melengkapi perannya dalam dunia hukum, Mochtar dengan koleganya antara lain Komar Kantaatmadja mendirikan kantor hukum MKK (Mochtar, Karuwin dan Komar). Singkat kata, Mochtar adalah figur yang memiliki banyak wajah dalam dunia hukum di Indonesia. Membaca dan memetakan gagasan Mochtar dalam lanskap pemikiran hukum di Indonesia tentunya harus mempermbangkan Mochtar sebagai sosok dengan mul wajah. Mengidenkkan Mochtar hanya dengan gagasannya mengenai peran hukum dalam pembangunan tentunya dak akan lengkap membaca sosok seorang Mochtar, karena ia juga seorang pemikir hukum internasional Indonesia par excellence, bahkan dak terlalu salah apabila ia ditahbiskan sebagai Bapak Hukum Internasional Indonesia. Selain itu, Mochtar adalah pakar hukum laut Indonesia kenamaan yang mengusung gagasan negara kepulauan (archipelagic state) ke forum internasional yang kemudian menjadi landasan awal bagi lahirnya konsep “Wawasan Nusantara”. -

The Role of Indonesia in Creating Peace in Cambodia: 1979-1992

Journal of Critical Reviews ISSN- 2394-5125 Vol 7, Issue 2, 2020 Review Article THE ROLE OF INDONESIA IN CREATING PEACE IN CAMBODIA: 1979-1992 1Ajat Sudrajat, 2Danar Widiyanta, 3H.Y. Agus Murdiyastomo, 4Dyah Ayu Anggraheni Ikaningtiyas, 5Miftachul Huda, 6Jimaain Safar 1Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta, Indonesia 2Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta, Indonesia 3Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta, Indonesia 4Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta, Indonesia 5Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris Malaysia 6Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Received: 05.11.2019 Revised: 25.12.2019 Accepted: 07.01.2020 Abstract The 1979-1992 conflicts were a thorn in the flesh for the peace in the Indochina area, and the Southeast Asia area. Because Indonesia is part of the countries in Southeast Asia, it is reasonable if Indonesia contributes to creating peace in Cambodia. Therefore, this study tried to find out the beginning of the conflict in Cambodia, to know the role of Indonesia in realizing peace in Cambodia in 1979-1992, and to understand how the impact of Cambodia peace for Indonesia in particular and Southeast Asia in general. The conflict in Cambodia caused political uncertainty in Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia countries attempted either independently or within the framework of ASEAN to resolve the conflict. Indonesia’s extraordinary contribution assisted in the peace in Cambodia, both through ASEAN and the United Nations. Indonesia as the representative of ASEAN, has successfully held several important meetings as a solution to solving Cambodia's problems. Successive is Ho Chi Minh City Understanding (1987), and Jakarta Informal Meeting (JIM) I and II (1988-1989). In the United Nations Framework, the Indonesian Foreign Minister and the French Foreign Minister were appointed Chairman, at the 1989 Paris International Conference on Cambodia (PICC-Paris International Conference on Cambodia). -

The Crisis of Judicial Independence in Indonesia Under Soeharto Era

Scientific Research Journal (SCIRJ), Volume III, Issue VIII, August 2015 6 ISSN 2201-2796 THE CRISIS OF JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE IN INDONESIA UNDER SOEHARTO ERA Dr. A. Muhammad Asrun, SH, MH Lecturer at the Law Faculty and Chairman of the Graduate Legal Studies Program, University of Pakuan, Bogor, WEST JAVA Email: [email protected] Abstract: The significant intervention of the government of the judicial power under the era of Soekarno and in the era of Soeharto has raised questions in the process toward the recent democratic government. Many scholars argue that previous interventions were considered important in stabilizing the state from political unrest, while others argue that such interventions cannot be tolerated anymore in the reform era now. This paper, using views and notes advanced in literatures discussed the crisis of judicial independence in Indonesia under Soeharto era. The study argued inter alia that the independence of the judicial authority in the present democratic political system should be considered as the principle of the equality before law for every citizen. The judicial process should also be independent as mandated in the 1945 Constitution and protect human rights regardless of race, gender, cultural background, economic and political conditions and the principle of legal certainty. Index Terms: The judicial power, the equality before law, the intervention of government, separation of power, era of Soeharto. I. INTRODUCTION The significant intervention of the government on judicial independence in Indonesia that happened in the era of Guided Democracy under the President Soekarno and in the era of the New Order government under President Soeharto has been questioned by many scholars recently. -

Menghargai Jasa-Jasa Prof. Mochtar Kusumaatmadja

JURNALISME WARGA I RABU, 23 JUNI I TAHUN 2021 I HALAMAN 3 Layangkan unek-unek dan keluhan Anda terkait berbagai persoalan, ANDA layanan publik, lingkungan, kinerja MENULIS aparat baik pemerintahan maupun kepolisian, serta KAMI pelayanan umum lainnya. PUBLIKASIKAN Kirim langsung ke : [email protected] email: [email protected] web: radarbekasi.id [email protected] NOMOR TELEPON PENTING AMBULANS Kota/Kabupaten Bekasi 0813-8268-6114 PEMADAM KEBAKARAN Kota/Kabupaten Bekasi 021-88957805 / 021-22162577 Palang Merah IndonesIa (PMI) Kota/Kabupaten Bekasi 021-88960247 / 021-88331414 PEMERINTAH Kota/Kabupaten Bekasi 021-88961767 / 021-89970065 TERMINAL Kota Bekasi/Cikarang 021-89107256 / 0812-8415-0944 STASIUN PT KAI 021-3453535 GANGGUAN LISTRIK PLN UP3 Bekasi /Cikarang 021-8812222 / 021-897445 ARIESANT/RADAR BEKASI GANGGUAN TELEPON Telkom STO Bekasi 0812-8855-6975 PERBAIKAN JALAN BENCANA ALAM Sejumlah pekerja melakukan perbaikan Jalan Tol Jakarta-Cikampek Km 36 Cikarang Pusat Kabupaten Bekasi. Perbaikan tersebut seiring dengan BPBD Kota/Kabupaten Bekasi 021-1500444 / 021-89970506 naiknya tarif Tol Jakarta-Cikampek. RUMAH SAKIT RSUD Kota/Kabupaten Bekasi 021-89452690 / 021-88374444 JALAN TOL Jakarta Cikampek 021-821 6515 Jagorawi 021-8413632 Jakarta Tangerang 021-5575 3904 Palikanci 021- 489800 Menghargai Jasa-jasa Purbaleunyi 021-200 0867 PDAM Tirta Bhagasasi 021-8894384 Tirta Patriot 021-88966161 BPJS Prof. Mochtar Kusumaatmadja Kesehatan Bekasi/Cikarang 021-8847071 / 021-4946474 Ketenagakerjaan Bekasi Kota/Cikarang 021-8843909 / 021-89113873 Oleh: Etty Agus dan Prof. Dr. Ganjar sebagai Prinsip Negara Kepu- tidak hanya memusatkan pada banyak buku-buku dan doku- KEPOLISIAN Kurnia, guru besar Fakultas lauan, dan kemudian popular hukum laut, tetapi juga hukum men penting beliau yg disim pan Polres Metro Bekasi Kota 021-8841110 DR. -

Security Council Distr

UNITED NATIONS S Security Council Distr. GENERAL S/15965 8 September 1983 ORIGINAL8 ENGLISH LETTER DATED 8 SEPTEMBER1983 FROM THE PERMANENTREPRESENTATIVE OF INDONESIA To THE UNITED NATIONS ADDRESSED10 THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL Upon instructions from my Government, I have the honour to forward herewith the position of the Government and people of Indonesia with regard to the incident involving the destruction of a South Korean air liner on the morning of 1 September 1983, as reflected in the statement made by Prof. Dr. Mochtar Kusumaatmadja, Foreign Minister of the Republic of Indonesia, in Jakarta on 3 September 1983 and in those made by other Indonesian officials. 1. The downing last week of a South Korean civilian air liner by Soviet military aircraft has aroused shock and indignation among the Indonesian people. They were deeply saddened by the loss of life of 269 innocent passengers and crew members. These sentiments have found expression in statements made by Members of Parliament as well as in spontaneous demonstrations, inter alia, by members of the Indonesian pilots' association, civil aviation workers and students. 2. Indonesia views the shooting down of the civilian aircraft as a serious incident for which the Soviet Upion should bear responsibility by at the least providing a full account as to what happened on that fateful day. Indonesia further believes that, as the Soviet Union possesses the necessary technological capability to prevent such an occurrence, there appears to be no justification for the shooting down of a defenceless civilian aircraft even though it might have strayed into the airspace of the Soviet Union. -

Plagiat Merupakan Tindakan Tidak Terpuji

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI KARIER ADAM MALIK DALAM PENTAS POLITIK DI INDONESIA TAHUN 1959-1983 SKRIPSI Diajukan Untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah Oleh : Hesty Riana Ledes NIM: 051314010 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN ILMU PENGETAHUAN SOSIAL FAKULTAS KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2011 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI KARIER ADAM MALIK DALAM PENTAS POLITIK DI INDONESIA TAHUN 1959-1983 SKRIPSI Diajukan Untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah Oleh : Hesty Riana Ledes NIM: 051314010 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN ILMU PENGETAHUAN SOSIAL FAKULTAS KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2011 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI iii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI MOTTO “Tuhan Menjadikan Semuanya Indah pada Waktunya” “Siapapun boleh tertawa melihatku bersusah payah tuk meraih apa yang kuimpikan, tetapi mereka takkan pernah melihatku putus asa dan terjatuh”. “Guru/Dosen mengajarkan kita teori tentang kesabaran & kekuatan, prakteknya, pengalaman/masalah hiduplah yang mengajarkan”. iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN Dengan penuh rasa syukur atas kehadirat Tuhan Yang Maha Esa, Tugas Akhir ini saya persembahkan untuk: Tuhan Yesus Kristus, Atas Anugerah-Nya yang sungguh luar biasa dalam hidupku Orang tuaku tercinta, bapak Andria Putra & Ibu Duna, yang telah membesarkanku dengan penuh kasih sayang, dan banyak memberikan dukungan serta doa, sehingga aku bisa menyelesaikan pendidikanku dengan baik. Adik-adikku, Riduan, Wiwin, dan Oyo, yang telah memberi dukungan, semangat dan doa. Abangku tersayang “Adianus Mustra Adisulastro”, yang selalu memberikan motivasi, kasih sayang, cinta, dan doa, sehingga aku mampu melewati semuanya dan mampu menyelesaikan skripsi ini dengan baik.