Two Cheers for the First Amendment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

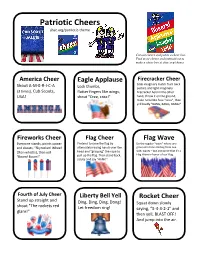

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

MISCELANEA 60.Indb

FRASIER: A CULTURAL HISTORY Joseph J. Darowski and Kate Darowski Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017 ROBERT MURTAGH Universidad de Almería [email protected] 177 Part of independent publisher Rowman & Littlefield’s “Cultural History of Television” series that (according to their website) “will focus on iconic television shows” from the 1950s to the present that have had a lasting impact on world culture, Frasier: A Cultural History joins a collection of extant publications on defining sitcoms such as Mad Men, Breaking Bad and Star Trek. The authors of the text in question, Joseph J. Darowski and Kate Darowski, are self-confessed Frasier fans with a background in different ambits of cultural study (the former as editor of the “Ages of Superheroes” essay series and author of X-Men and the Mutant Metaphor: Race and Gender in the Comic Books and the latter having researched the history of decorative arts and design). Above all, they share a mutual appreciation for all things Crane. From a structural perspective, the book is divided into two parts: “Part I: Making A Classic” and “Part II: Under Analysis”. Each section is further subdivided into four separate topics. The first deals with: the evolution of Cheers to the emergence of Frasier Crane; the story behind the eclectic cast; character profiles of Frasier, Niles, Martin and Eddy; and finally, a discussion of Daphne and Roz. The second part, as the name suggests, is more academically inclined with chapters examining ongoing character development in the Crane household; an in-depth look at Frasier’s apartment from structural and aesthetic perspectives, as well as in contrast to Niles’s home at the Montana; an analysis of set decoration, particularly chairs; and lastly, the representation of women, gender and race. -

An Opportunity Lost: the United Kingdom's Failed Reform of Defamation Law

Federal Communications Law Journal Volume 49 Issue 3 Article 4 4-1997 An Opportunity Lost: The United Kingdom's Failed Reform of Defamation Law Douglas W. Vick University of Stirling Linda Macpherson Heriot-Watt University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj Part of the Communications Law Commons, and the European Law Commons Recommended Citation Vick, Douglas W. and Macpherson, Linda (1997) "An Opportunity Lost: The United Kingdom's Failed Reform of Defamation Law," Federal Communications Law Journal: Vol. 49 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj/vol49/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Federal Communications Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Opportunity Lost: The United Kingdom's Failed Reform of Defamation Law Douglas W. Vick* Linda Macpherson** INTRODUCTION ..................................... 621 I. BACKGROUND OF THE ACT ....................... 624 I. THE DEFAMATION ACT 1996 ...................... 629 A. The New Defenses ......................... 630 B. The ProceduralReforms ..................... 636 C. Waiving ParliamentaryPrivilege ............... 643 III. AN OPPORTUNITY LOST ......................... 646 CONCLUSION ....................................... 652 INTRODUCTION The law of defamation in the United Kingdom remains -

•Now Pitcbincj: Sam Malone• Written by Ken Levine, David Isaacs

, CBDRS •Now PitcbincJ: Sam Malone• 160591-016 Written By Ken Levine, David Isaacs Created and Developed By James Burrows Glen Charles Les Charles Return to Script Department PARAMOUNT PIC'l'traES CORPORATION PINAL DRAFT 5555 Melrose Avenue Hollywood, California 90038 December 9, 1982 CBEBRS •Now Pitcbin91 ~ SAM MALONE ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• DD DANSON DIANE CBAMBERS ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• SBBLLBY LONG COACH ERNll PANTUSSO ••••• •••••••••••••••••• NICX COLASANTO CARLA TORffLLI • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • RHEA PERLMAN CI.IPF • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. • JORN' RA'tZENBERGER NORM. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • GEORGB 1IENDT LANA MARSHALL •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• BARBARA BABCOCK TIBOR SVE'l'KOVIC. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • RICX BILL PAUL.. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •.• • • PAOL VAUGHN LUIS TIANT ••••••••• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • BIMSBLF DIRECTOR ••••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••• • ••• nrr. BAR INT. SAM'S OFFICE CHBBRS •Nov Pitching: Sam Malone• .. TEASER -X FADE IN: INT. BAR - CLOSING TIME SAM AND COACH ARE CLOSING tJP. AS THEY HEAD FOR THE DOOR, COACH STOPS AND LOOKS AROUND. COACH Y'know Sam, this is my favorite time of day. SAM Closing time, Coach? COACH No, 1:37. SOmething about it, I don't know ••• SAM Yeah, it's nice. Everybody's probably got their favorite 1:37 story. 2. (X) 1eah. What time of day do you like, S&m? SAM Gee, I don't Jcnow ••• 8115'• nice. COACH I used to like 8:15, but I kinda outgrew it. AS THBY 'l'ALK, SAM 'l'tJRNS 00'1' THE LIGHTS. 'l'BBY GO 00'1' 'l'HB DOOR, UP '1'BB S'l'EPS AND DISAPPEAR. AP'l'ER A BEA'l' NORM COMES ROSSING QY! OP 'l'HB BATHROOM. NORM Wait a minute, I ••• BB STOPS, A THOOGH'l' OCCURS TO HIM. HE LOOKS AROUND,; GOES OVER AND TtJRNS ON 'l'HE TV. -

UCLA the Docket

UCLA The Docket Title The Docket Vol. 51 No. 5 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7nm80349 Journal The Docket, 51(5) Author UCLA Law School Publication Date 2003-03-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW. VOLUME 51, NUMBER 5 405 H1LGARD AVENUE, Los ANGELES, CA 90095. MARCH 2003 UCL tudent Take a tand Marky Keaton I was writing to the Supreme Court. In 3L stead, I realized for the first time that I was writing what I felt. I and my con As many of you are aware, in the patriots were addressing the severe harm next couple of months the Supreme Court caused to a large number of students at will decide the fate ofaffirmative action our school. It is this harm that we be in this country in Grutter v. Bollinger lieve must be faced head-on instead of ("Grutter"). Our class was in a unique hidden in the background. position as we were part of the first gen In the.process, we learned things that eration of students to be admitted and were both touching, disturbing, and in educated in California without race-con spirational. Several students in SCARE scious admissions policies. We were the worked on soliciting testimonials for the first victims of Proposition 209 _and · brief from other UC law students. The could personally attest to the detrimen response from students at Berkeley, tal effect of the proposition on all stu Hastings, and Davis was overwhelming, dents at the UCLA School of Law and powerful, and immP.diate. -

Post-Legislative Memorandum: the Defamation Act 2013

Post-Legislative Memorandum: The Defamation Act 2013 October 2019 CP 180 Post-Legislative Memorandum: The Defamation Act 2013 Presented to Parliament by the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice by Command of Her Majesty October 2019 CP 180 © Crown copyright 2019 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/official-documents Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at Civil Law Policy Team Civil Justice and Law Division, Post Point 10.18 Ministry of Justice 102 Petty France London SW1H 9AJ [email protected] . ISBN 978-1-5286-1634-8 CCS1019227570 10/19 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Post-Legislative Memorandum: The Defamation Act 2013 Contents Introduction 3 Objectives 3 Background 3 Summary of Changes made by the Act 4 Implementation 6 Secondary Legislation 6 Legal Issues 6 Other Reviews 6 Preliminary Assessment of the Act 7 1 Post-Legislative Memorandum: The Defamation Act 2013 2 Post-Legislative Memorandum: The Defamation Act 2013 Introduction 1. This post-legislative memorandum is being published as part of the post- legislative scrutiny process set out in Cm 7320, and is being submitted in the first instance to the Justice Select Committee. -

Written Constitution for the UK

Contents Page Mapping the Path towards Codifying - or Not Codifying - the UK Constitution ROBERT BLACKBURN, PhD, LLD, Solicitor Professor of Constitutional Law Centre for Political and Constitutional Studies King's College London PROGRAMME OF RESEARCH Aims This programme of research has been prepared at the formal request1 of the House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee chaired by Graham Allen MP to assist its inquiry, and the policy debate generally, on the proposal to codify - or not - the UK constitution. The work been prepared in an impartial way, adopting a pragmatic approach to the issues involved, and does not seek to advocate either codification or non-codification. Its purpose is to inform the inquiry of the issues involved and, in the event that a government in the future might wish to implement such a proposal, it seeks to provide a starting point and set of papers to help facilitate the complex and sensitive issues of substance and process that would be involved. Structure of the Research The content starts (Part I) by identifying, and giving a succinct account of, the arguments for and against a written constitution, prepared in rhetorical manner. It then (Part II) sets out a series of three illustrative blueprints, prepared in the belief that a consideration of detailed alternative models on how a codified constitution might be designed and drafted will better inform and advance the debate on the desirability or not of writing down the constitution into one documentary source. These are - (1) Constitutional Code - a document sanctioned by Parliament but without statutory authority, setting out the essential existing elements and principles of the constitution and workings of government. -

Cheers Or Jeers by Reg P. Wydeven January 24, 2016

Cheers or Jeers By Reg P. Wydeven January 24, 2016 A few weeks ago, the Kimberly High School basketball program honored the 1991 team that qualified for the State Tournament. To commemorate the 25th anniversary of our trip to State, they held a ceremony between the JV and varsity games. Flanked by the current players, my buddies and I walked out to the center of Jack Wippich Court as the PA announcer recounted the highs and lows of that memorable season. After the game, we went to Tanners to continue the celebration. We told old stories for the 1,000th time and laughed until our faces hurt. I recalled the time during our junior year that we played Fox Valley Lutheran in a junior reserve game on a Saturday morning. I loved playing FVL because they utilized a 2-3 zone, so that opened up 3-point shots. Sure enough, early in the game I was wide open for a 3. Apparently I was so excited that when I launched it, the shot came up about a foot short. The half-dozen or so students at the game immediately began chanting “Airball, airball!” For the rest of the game, the fans resumed the chant each time I touched the ball. I was reluctant to jack up another shot out of fear of further ridicule. Thankfully, my love for shooting outweighed my fear of humiliation, so I kept shooting. A quarter century later, that handful of fans could get in trouble for picking on me. In case you haven’t heard, last month the WIAA sent out an email to member schools reminding them about the organization’s policy about sportsmanship and student section chants directed at opponents that “are clearly intended to disrespect.” The email, sent by director of communication Todd Clark, included examples of such chants, such as “You can’t do that,” “Fundamentals,” “There’s a net there,” “Sieve,” “We can’t hear you,” the “scoreboard” cheer and “season’s over” during tournament play. -

CHEERS Checklist 1

Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards – CHEERS Checklist 1 CHEERS Checklist Items to include when reporting economic evaluations of health interventions The ISPOR CHEERS Task Force Report, Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS)—Explanation and Elaboration: A Report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluations Publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force, provides examples and further discussion of the 24-item CHEERS Checklist and the CHEERS Statement. It may be accessed via the Value in Health or via the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines – CHEERS: Good Reporting Practices webpage: http://www.ispor.org/TaskForces/EconomicPubGuidelines.asp Section/item Item Recommendation Reported No on page No/ line No Title and abstract Title 1 Identify the study as an economic evaluation or use more specific terms such as “cost-effectiveness analysis”, and describe the interventions compared. Abstract 2 Provide a structured summary of objectives, perspective, setting, methods (including study design and inputs), results (including base case and uncertainty analyses), and conclusions. Introduction Background and 3 Provide an explicit statement of the broader context for the objectives study. Present the study question and its relevance for health policy or practice decisions. Methods Target population and 4 Describe characteristics of the base case population and subgroups subgroups analysed, including why they were chosen. Setting and location 5 State relevant aspects of the system(s) in which the decision(s) need(s) to be made. Study perspective 6 Describe the perspective of the study and relate this to the costs being evaluated. Comparators 7 Describe the interventions or strategies being compared and state why they were chosen. -

"He's Everything You're Not . . ."1 a Semiological Analysis of Cheers

"HE'sEvtnvrHrNcYou'nnNor..." Bsncsn . 229 "He's Everything You're Not . ."1 A SemiologicalAnalYsis of Cheers Arthur AsaBetger T Is it symbolicthat DianeChnmbers, one of theoriginal leads in thesit- com Cheer,s,has blond hair? why doesCarla the waitresshaae a temperand by the nameNorm? These kid aroundso frankly aboutsex? what is signit'ied Bergersets out to answ-erin his are justa 7ew"o7 tne questions that Arthur Asa semiologicalaialysis of oneof themost popular situation comedies of all time. Takingiis criticil poiition the structuralistsFerdinand Saussure and "reads'"from llmbirto Eco,Berger the text o/Cheers throughthe l-ens of sem.iotics' For Berger,this riading is a processof decodinga text and of interpretingthe signsyitems it contaiis.He'defines a sign as a unit madeup of a soundimage oid ,"rorrrpt---or, in the terminologyof thestructuralists, of a signifierand a signified." 'Brrg* is carefulto point out that thesign is not na1nal; in otherwords, blondhair means sometiting to us not becnusethere is a naturalconnection be- "meaning," tweenblond hair and itssi-catted but becauseof thecultural and it with. Therules establishinga re- historicalaalues that we haae inaested for " lationshipbetween the signifier and thesignified, then, are called codes,"and thesecodes tells us whal signsmean. When this type of semioticstudy is ap' subtexts,or concealedmeanings, 'comepliedto a situationcomedy, some interesting to tight. For exampli,the bnr itselfmay signtfu more- than iusj^a building thecharacters can buy atcohoi. lts geographical location (Bostod and in which "classier" its interior decoratingsuggrti that it is than a collegeor zootking classbar. For Berger,"botii1tnese signiJiers giae the Cheers bar a meaningbe- yond itsdictionary definition.