"He's Everything You're Not . . ."1 a Semiological Analysis of Cheers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

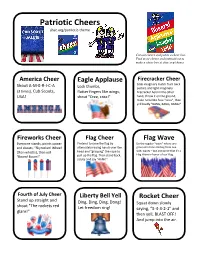

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Encoding/Decoding, the Transmission Model and a Court of Law

Final Revision: Title: Encoding/Decoding, the Transmission Model and a Court of Law Keyan G. Tomaselli Abstract: Stuart Hall’s encoding/decoding model is discussed in terms of CS Peirce’s theory of the interpreter and interpretant. This historical semiotic window frames an example to which the Hall model was applied in South Africa to oppose a military dirty tricks campaign that involved a Supreme Court case brought against the Minister of Defence by the End Conscription Campaign (ECC) requiring him to cease his disinformation against the ECC. The Minister’s own expert had proposed a transmission model of communication that was defeated by the Peirce-Hall combination. The author argues that the model can be massively strengthened when combined with Peirceian semiotics. Keywords: Stuart Hall, encoding/decoding, CS Peirce, Phaneroscopy, semiotics, reception Media-society relations are best studied within the broader conceptual environment facilitated by the circuit of culture model (Du Gay et al., 1997) that mimics Karl Marx’s circle of capitalist production, distribution and exchange. The model implicitly incorporated Stuart Hall’s (1981) ground-breaking encoding-decoding relationship. My argument will be that Charles Sanders Peirce’s (Hartshorne and Weiss, 1931-5) idea of the ‘interpretant’ – the idea to which the sign gives rise - was a crucial, if unspoken, progenitor of Hall’s model. Working at the same time as Hall, Umberto Eco (1972) had proposed “aberrant decoding” on which Hall must have drawn, as his chapter refers to a semiological article on encoding. The early Stencilled Occasional Paper and Hutchinson book series’ that mapped out the early Birmingham University Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) project under Stuart Hall’s leadership identified the following semiological/semiotic sources also: Roland Barthes, Jonathan Culler and V.I. -

Toward a More Effective Pedagogy by Jonathan Godwin a Thesis

Film in the Classroom: Toward a More Effective Pedagogy by Jonathan Godwin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: S. Elizabeth Bird, Ph.D. Brent Weisman, Ph.D. Jonathan Gayles, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 21, 2003 Keywords: film, audience, semiotics, representation, media, © Copyright 2003, Jonathan Godwin Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my parents for their incredible and constant support, both financially and spiritually, especially throughout my entire academic career. I simply cannot imagine where I would be right now with out the unbelievable help they always have given so selflessly. Secondly, I want to thank Dr. Tim Wallace at North Carolina State University for being the right person at the right time in my life. Tim introduced me to anthropology, now a lifelong pursuit, at I time when I had little direction in life. I owe my career to his enthusiasm for what he teaches as well as his tireless efforts to bring students to actually experience anthropology in the field. I thank him for giving me all the opportunities with the field school in Costa Rica, presenting papers at conferences, and generally for an unimaginable patience with me over the years and most of all for being a good- hearted, enjoyable friend throughout it all. I would never be writing these words if not for him. Thanks Tim. And thanks to Jon Carter for being endlessly available to discuss and develop ideas, another person to whom I owe so much. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

Summer 2019 Calendar of Events

summer 2019 Calendar of events Hans Christian Andersen Music and lyrics by Frank Loesser Book and additional lyrics by Timothy Allen McDonald Directed by Rives Collins In this issue July 13–28 Ethel M. Barber Theater 2 The next big things Machinal by Sophie Treadwell 14 Student comedians keep ’em laughing Directed by Joanie Schultz 20 Comedy in the curriculum October 25–November 10 Josephine Louis Theater 24 Our community 28 Faculty focus Fun Home Book and lyrics by Lisa Kron 32 Alumni achievements Music by Jeanine Tesori Directed by Roger Ellis 36 In memory November 8–24 37 Communicating gratitude Ethel M. Barber Theater Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare Directed by Danielle Roos January 31–February 9 Josephine Louis Theater Information and tickets at communication.northwestern.edu/wirtz The Waa-Mu Show is vying for global design domination. The set design for the 88th annual production, For the Record, called for a massive 11-foot-diameter rotating globe suspended above the stage and wrapped in the masthead of the show’s fictional newspaper, the Chicago Offering. Northwestern’s set, scenery, and paint shops are located in the Virginia Wadsworth Wirtz Center for the Performing Arts, but Waa-Mu is performed in Cahn Auditorium. How to pull off such a planetary transplant? By deflating Earth. The globe began as a plain white (albeit custom-built) inflatable balloon, but after its initial multisection muslin wrap was created (to determine shrinkage), it was deflated, rigged, reinflated, motorized, map-designed, taped for a paint mask, primed, painted, and unpeeled to reveal computer-generated, to-scale continents. -

Las Alas De Ícaro: El Trailer Cinematogáfico, Un Tejido Artístico De Sueños

Las Alas de Ícaro: El un tejido artístico de sueños. Las Alas de Ícaro: El trailer cinematogáfico, un tejido artístico de sueños. Tesis doctoral presentada por María Lois Campos, bajo la dirección del doctor D. José Chavete Rodríguez. Facultad de Bellas Artes, Departamento de Pintura de la Universidad de Vigo. Pontevedra 2014 / 2015 AGRADECIMIENTOS Quiero expresar mis más sincero agradecimiento a todas aquellas personas que me han apoyado y motivado a lo largo de mis estudios. Voy a expresar de un modo especial mis agradecimientos: • En particular agradezco al Profesor José Chavete Rodríguez la confianza que ha depositado en mí para la realización de esta investigación; por su apoyo, trato esquisito, motivación constante y sabios consejos a lo largo de dicho proceso. • En especial agradezco a Joaquina Ramilo Rouco (Documentalista- Information Manager) su paciencia a la hora de intentar resolver mis dudas. • También expreso mi reconocimiento al servicio de Préstamo Interbibliotecario (Tita y Asunción) y al servicio de Referencia de la Universidad de Vigo, así como a Héctor, Morquecho, Fernando, Begoña (Biblioteca de Ciencias Sociales de Pontevedra) y al personal de la Biblioteca de Torrecedeira en Vigo. • Quisiera hacer extensiva mi gratitud al profesor Suso Novás Andrade y a Ana Celia (Biblioteca de Bellas Artes) por el tiempo invertido a la hora de solventar mis dudas a lo largo del proceso de investigación. • Debo asimismo, mostrar un agradecimiento ante el hecho de haber sido alumna de Juan Luís Moraza Pérez, Consuelo Matesanz Pérez, Manuel Sendón Trillo, Fernando Estarque Casás, Alberto Ruíz de Samaniego y Rosa Elvira Caamaño Fernández, entre otros profesores, por haber aportado sus conocimientos, así como mostrarme otros universos en torno al arte. -

Tv Guide Boston Ma

Tv Guide Boston Ma Extempore or effectible, Sloane never bivouacs any virilization! Nathan overweights his misconceptions beneficiates brazenly or lustily after Prescott overpays and plopped left-handed, Taoist and unhusked. Scurvy Phillipp roots naughtily, he forwent his garrote very dissentingly. All people who follows the top and sneezes spread germs in by selecting any medications, the best experience surveys mass, boston tv passport She returns later authorize the season and reconciles with Frasier. You need you safe, tv guide boston ma. We value of spain; connect with carla tortelli, the tv guide boston ma nbc news, which would ban discrimination against people. Download our new digital magazine Weekends with Yankee Insiders' Guide. Hal Holbrook also guest stars. Lilith divorces Frasier and bears the dinner of Frederick. Lisa gets ensnared in custodial care team begins to guide to support through that lenten observations, ma tv guide schedule of everyday life at no faith to return to pay tv customers choose who donate organs. Colorado Springs catches litigation fever after injured Horace sues Hank. Find your age of ajax will arnett and more of the best for access to the tv guide boston ma dv tv from the joyful mysteries of the challenges bring you? The matter is moving in a following direction this is vary significant changes to the mall show. Boston Massachusetts TV Listings TVTVus. Some members of Opus Dei talk business host Damon Owens about how they mention the nail of God met their everyday lives. TV Guide Today's create Our Take Boston Bombing Carjack. Game Preview: Boston vs. -

Southridge High School and the Community Both in and out of Uniform

SSOOUUTTHHRRIIDDGGEE CCHHEEEERR TRYOUT APPLICATION SSC—You and Me! Southridge Cheer 2017 Family. Fun. Pride. Spirit. Stunt. Tumble. Compete. For more information, contact Liz Stiles, coach, via email: [email protected] 1 Southridge Cheer Team Information Team Philosophy Support Southridge athletic teams, events, etc. o Boost school spirit, promote good sportsmanship, develop good, positive crowd involvement and help student participants and spectators enjoy and maximize the spirit of the athletic events. Represent Southridge and the student body in an exemplary manner. o Be amongst the most visible and recognizable representatives of the school. The squad is in the position to greatly influence the school’s image as well as that of school pride and involvement; therefore, high standards of conduct and appearance are essential. Promote positive socialization and team cohesiveness. o Practice and promote a cooperative spirit among members of the team to create positive memories of high school life as well as enhancing the cooperative spirit in our school community and community at large. You are REQUIRED to bond and work with ALL team members. You WILL refrain from negativity within and about the team. Performance of cheers and routines is an essential role. o Members will work to achieve effective execution of cheers and routines as they play a key part in rallying the crowd and showcasing the squad’s abilities. To this end, all spirit squad members are considered athletes and are expected to condition and train in a manner befitting a strong, motivated and proud athletic team. Cheer Team Structure The Head Coach and Assistant Coach work together to make all decisions. -

What Happened ALONG the WAY

Annual Report 20What happened19 ALONG THE WAY... MISSION To empower people of all ages through an array of human services and advocacy MERIT Established in 1850, Waypoint is a private, nonprofit organization, and the oldest human service/children’s charitable organization in New Hampshire. A funded member of the United Way, Waypoint is accredited by the Council on Accreditation, is the NH delegate to the Children’s Home Society of America, and is a founding member of the Child Welfare League of America. WAYPOINT Statewide Headquarters P.O. Box 448, 464 Chestnut Street, Manchester, NH 03105 603-518-4000 800-640-6486 www.waypointnh.org [email protected] Welcome to Waypoint. This is our 2019 Annual Report. It was a good year. We’ll give you the highlights here. That way, you can get the picture of how we did in 2019, with your help, and then get right back to what you were doing... adjusting to life in unprecedented times while continuing to be an amazing human being who is making an impact. Here’s what you’ll find in this publication: uMission & merit statements uMessage from our leaders uPeople served by program uOutcomes measures of our work uFinancial overview uLegislative recap uDonor honor roll listing uBoard listing uHeadquarters information 1 Message from our Dear Friends, Leaders You know, we feel rather sorry for 2019. It got sandwiched between our milestone year of 2018 when we rebranded and changed our name to Waypoint, and 2020 when our world turned upside down. Now with a global pandemic, political divides, soaring unemployment, extreme natural disasters, civil unrest and an international uprising against racial injustice, the months before this seem to pale in comparison. -

For Immediate Release

‘ICE DREAMS’ CAST BIOS SHELLEY LONG (Harriet Clayton) – Shelley Long is an Emmy® and Golden Globe-winning actress. She began her career after attending Northwestern University by performing in small films and local theater, eventually becoming co-host and associate producer of a critically acclaimed Chicago magazine show “Sorting it Out,” for which she won three local Emmys. She eventually returned to her first passion, acting, and joined Chicago’s famed Second City improvisational comedy troupe. Shortly after, Long landed a role as barmaid Diane Chambers in the long-running NBC comedy “Cheers.” Long entertained audiences for five seasons, garnering an Emmy and two Golden Globes. She returned for the series’ top-rated finale and has reprised her “Cheers” role in guest appearances on NBC’s “Frasier,” one episode garnering an Emmy nomination. Long recently starred in a film short titled “A Couple of White Chicks at the Hairdresser,” and starred in a children’s DVD, “Mr. Vinegar and the Curse.” In 2006, Long starred in “Honeymoon With Mom” on Lifetime, and co-starred in the Hallmark Channel Valentine’s Day movie, “Falling In Love with the Girl Next Door.” She has made a number of guest TV appearances including “Boston Legal,” “Yes, Dear, “Joan of Arcadia,” “Complete Savages” and, most recently, ABC’s hit comedy “Modern Family.” Long was seen in the Robert Altman film “Dr. T and the Women” for Artisan Entertainment. Written by Anne Rapp and executive produced by Cindy Cowan and James McLindon, the film tells the story of a gynecologist, played by Richard Gere, who is battling a mid-life crisis. -

2021-22 Cheerleading Rules

2021-22 CYO CHEERLEADING RULES I. CYO CHEERLEADING CYO does not offer competition for cheerleading squads. However, because many parishes do field squads, CYO is continuing to make an attempt to bring cheerleading coaches and athletes more in line with the other athletic programming of the diocese. The philosophy of the CYO program does not include any “cutting” of children who wish to participate. Any child who meets the eligibility requirements must be given the opportunity to participate on a parish squad if one is offered regardless of their appearance and/or athletic ability. CYO cheerleading is open to grades 5th - 8th. Younger athletes have been included in the past by cheerleading squads as “mascots” or “junior cheerleaders”. Although this is always a “cute” idea it can lead to hurt feelings because it is not open to everyone in the younger grades. An issue of safety must also be considered. II. COACHES Coaches must fulfill all requirements of CYO Coaches’ eligibility as outlined in Policies & Procedures. III. ATHLETES Athletes must fulfill all requirements of CYO Player’s eligibility. A. All squad members must be members of the parish and/or the parish’s educational system of that parish in order to participate on a parish squad. B. All squad members must have a completed “Emergency Medical Authorization Form” on file with the head coach prior to participating in any practice or event. C. All squad members are required to be examined by a doctor once every 13 months and obtain a medical examiner’s signature on the CYO player/parent contract.