Ideology and Early Modern Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of the Purcells of Ireland

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PURCELLS OF IRELAND TABLE OF CONTENTS Part One: The Purcells as lieutenants and kinsmen of the Butler Family of Ormond – page 4 Part Two: The history of the senior line, the Purcells of Loughmoe, as an illustration of the evolving fortunes of the family over the centuries – page 9 1100s to 1300s – page 9 1400s and 1500s – page 25 1600s and 1700s – page 33 Part Three: An account of several junior lines of the Purcells of Loughmoe – page 43 The Purcells of Fennel and Ballyfoyle – page 44 The Purcells of Foulksrath – page 47 The Purcells of the Garrans – page 49 The Purcells of Conahy – page 50 The final collapse of the Purcells – page 54 APPENDIX I: THE TITLES OF BARON HELD BY THE PURCELLS – page 68 APPENDIX II: CHIEF SEATS OF SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE PURCELL FAMILY – page 75 APPENDIX III: COATS OF ARMS OF VARIOUS BRANCHES OF THE PURCELL FAMILY – page 78 APPENDIX IV: FOUR ANCIENT PEDIGREES OF THE BARONS OF LOUGHMOE – page 82 Revision of 18 May 2020 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PURCELLS OF IRELAND1 Brien Purcell Horan2 Copyright 2020 For centuries, the Purcells in Ireland were principally a military family, although they also played a role in the governmental and ecclesiastical life of that country. Theirs were, with some exceptions, supporting rather than leading roles. In the feudal period, they were knights, not earls. Afterwards, with occasional exceptions such as Major General Patrick Purcell, who died fighting Cromwell,3 they tended to be colonels and captains rather than generals. They served as sheriffs and seneschals rather than Irish viceroys or lords deputy. -

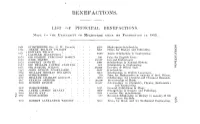

Benefactions

BENEFACTIONS. LIST (.iV PKilSTClTAL BENEFACTIONS. MAIM-: T<> TH.K UNIVKKSITY OK MELBOURNE SINOK ITS FOUNDATION IN 1S53. ISM SI.'IISCRIHEUS CSir. <i. W. IIUMIKX) ,tS.r'C Shilki.'spi.-arc Seln'Iai'ship. l,;7i IIENKV Tnl.MAN IrWUiHT fil 101' Rrizns for History and Education. -, l EHWARI1 WILSON" , '' ' "i LAC 11 LAN MACKINNON. ' 10(10 Avails Scholarship in Enu'itiL'iM-iii--. 1ST:; 'SIR CKllltliE l-'EIKilisr r.V HnWEN 1UII I'r-izu for English Essay. 1*7:; JOHN HASTIE .... I,s7:i OODI-'REY IK>\\ ITX Ill, till (IClli'l'lll KlllliiU'llltlllt 1S7:; Sill. WILLIAM l-'OSTKI! STAWELL 'WOO Scholarships hi N'lilnral History, ISS7:". SIK. SAMUEL WlLS'iN ririi'i Scholarship hi lOnirin^i'rin^. !*>:; JOHN IUXSON WYSELASKIE - Hfr.llllir Erection nf Wilson Hull. is.vl WILLIAM THOMAS Mi 1I.I.IS1 IX xnlO Scholarships 1,<S1 StinSCRIIiERS .... rilluli Scholarships in .Modern Luii^iiiiffcs. P-S7 WILLIAM CHARLES EEliXnT - l.Mi I'ri/n for- Mathematics in memory nf I'rof. Wilson, ls>7 l-'liANCIS ORMOMIl -.alilo Scholarships for Physical and Chemical .Re.Keareli. isrni Hi'rHERT lil.XSIlN L'II.OOII I'iorcssorship of Music. 10,s:r7 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathematics IS'" SLUSCIUDERS .... .•mil (-'.nuiiiL'i-'i'iii^. ,ri-17 Onnnnd Kxhihitions in Musi'-. IS!U JAMES CEIIKCiE HEAXEY :{!li.m Scholarships in Snrjrevy und Pathology. l.V.M I.1AVH1 KAY o7(;l .Caroline Kuy Scholarsnips, 1WI7 SUHSOlill.iERS 7;•'l,-l Research Scholarship in biology in memory of Sir .lames MacHain, I'.mj ROMERT ALEXANDER WHICHT lin'.o Prizes lor Music and ffir Mechanical Kn'.riiicel-inir. -

How the Elizabethans Explained Their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 Justification: How the Elizabethans Explained their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia Christopher Ludden McDaid College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McDaid, Christopher Ludden, "Justification: How the Elizabethans Explained their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625918. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4bnb-dq93 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Justification: How the Elizabethans Explained Their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fufillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Christopher Ludden McDaid 1994 Approval Sheet This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts r Lucfclen MoEfaid Approved, October 1994 _______________________ ixJLt James Axtell John Sel James Whittenourg ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................................. -

The Holinshed Editors: Religious Attitudes and Their Consequences

The Holinshed editors: religious attitudes and their consequences By Felicity Heal Jesus College, Oxford This is an introductory lecture prepared for the Cambridge Chronicles conference, July 2008. It should not be quoted or cited without full acknowledgement. Francis Thynne, defending himself when writing lives of the archbishops of Canterbury, one of sections of the 1587 edition of Holinshed that was censored, commented : It is beside my purpose, to treat of the substance of religion, sith I am onelie politicall and not ecclesiasticall a naked writer of histories, and not a learned divine to treat of mysteries of religion.1 And, given the sensitivity of any expression of religious view in mid-Elizabethan England, he and his fellow-contributors were wise to fall back, on occasions, upon the established convention that ecclesiastical and secular histories were in two separate spheres. It is true that the Chronicles can appear overwhelmingly secular, dominated as they are by scenes of war and political conflict. But of course Thynne did protest too much. No serious chronicler could avoid giving the history of the three kingdoms an ecclesiastical dimension: the mere choice of material proclaimed religious identity and, among their other sources, the editors drew extensively upon a text that did irrefutably address the ‘mysteries of religion’ – Foxe’s Book of Martyrs.2 Moreover, in a text as sententious as Holinshed the reader is constantly led in certain interpretative directions. Those directions are superficially obvious – the affirmation 1 Citations are to Holinshed’s Chronicles , ed. Henry Ellis, 6 vols. (London, 1807-8): 4:743 2 D.R.Woolf, The Idea of History in Early Stuart England (Toronto, 1990), ch 1 1 of the Protestant settlement, anti-Romanism and a general conviction about the providential purposes of the Deity for Englishmen. -

The Irish Soccer Split: a Reflection of the Politics of Ireland? Cormac

1 The Irish Soccer Split: A Reflection of the Politics of Ireland? Cormac Moore, BCOMM., MA Thesis for the Degree of Ph.D. De Montfort University Leicester July 2020 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements P. 4 County Map of Ireland Outlining Irish Football Association (IFA) Divisional Associations P. 5 Glossary of Abbreviations P. 6 Abstract P. 8 Introduction P. 10 Chapter One – The Partition of Ireland (1885-1925) P. 25 Chapter Two – The Growth of Soccer in Ireland (1875-1912) P. 53 Chapter Three – Ireland in Conflict (1912-1921) P. 83 Chapter Four – The Split and its Aftermath (1921-32) P. 111 Chapter Five – The Effects of Partition on Other Sports (1920-30) P. 149 Chapter Six – The Effects of Partition on Society (1920-25) P. 170 Chapter Seven – International Sporting Divisions (1918-2020) P. 191 Conclusion P. 208 Endnotes P. 216 Sources and Bibliography P. 246 3 Appendices P. 277 4 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my two supervisors Professor Martin Polley and Professor Mike Cronin. Both were of huge assistance throughout the whole process. Martin was of great help in advising on international sporting splits, and inputting on the focus, outputs, structure and style of the thesis. Mike’s vast knowledge of Irish history and sporting history, and his ability to see history through many different perspectives were instrumental in shaping the thesis as far more than a sports history one. It was through conversations with Mike that the concept of looking at partition from many different viewpoints arose. I would like to thank Professor Oliver Rafferty SJ from Boston College for sharing his research on the Catholic Church, Dr Dónal McAnallen for sharing his research on the GAA and Dr Tom Hunt for sharing his research on athletics and cycling. -

Creating Living Institutions EU Cross-Border Co-Operation After the Good Friday Agreement Brigid Laffan Diane Payne Institute for British-Irish Studies, UCD

A Report for the Centre for Cross Border Studies Creating Living Institutions EU Cross-Border Co-operation after the Good Friday Agreement Brigid Laffan Diane Payne Institute for British-Irish Studies, UCD May 2001 Creating Living Institutions EU Cross-Border Co-operation after the Good Friday Agreement Brigid Laffan Diane Payne May 2001 1 About the Authors Professor Brigid Laffan (Institute for British-Irish Studies) is a specialist in public policy making and in the policy process of the European Union. She is in the process of completing a study on the management of EU business in Dublin. This work will be published as a Trinity Blue Paper entitled “Organising for a Changing Europe: Irish Central Government and the European Union” in 2001. Dr Diane Payne (Institute for British-Irish Studies) has completed a major research project which focused on the EU structural funds policy decision making process in Ireland and examined the nature of multilevel policy making process therein. More recently she has completed a second research project which focused on local and regional economic policy making in the UK. The Institute for British-Irish Studies (IBIS) was founded in 1999 and is based in the Department of Politics at University College Dublin. The main aims of the Institute are: to promote and conduct academic research in the area of relations between the two major traditions on the island of Ireland, and between Ireland and Great Britain; to promote and encourage collaboration with academic bodies and with individual researchers elsewhere who share an interest in the exploration of relations between different national, ethnic or racial groups; to promote contact with policy makers and opinion formers outside the university sector, and to ensure a free flow of ideas between the academic and the non- academic worlds; and to contribute to public debate and public awareness of the evolving relations between communities within the island of Ireland and between Ireland and Great Britain. -

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

'The Registered Papers of the Chief Secretary's Office'

‘The Registered Papers of the Chief Secretary’s Office’ Tom Quinlan, Archivist, National Archives Journal of the Irish Society for Archives, Autumn 1994 The Registered Papers of the Chief Secretary’s Office consist of two main archival series covering the years 1818 to 1924, together with a number of sub-series of shorter date span within this period: They provide the researcher with valuable primary source material for research into Irish history during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The collection, which forms part of the Irish state papers, is now in the custody of the National Archives and is stored on site at its premises on Bishop Street in Dublin. There is a distinction between archives we describe as state papers and those we call public records which is not always articulated and hence tends to remain vaguely understood, The distinction has its basis in developments in England where the records created by the courts, by commissions of enquiry, and by public offices and boards were regarded as being of a public nature, whereas the records of secretaries of state were viewed as the semi-private papers of a government minister and, as such, were not deemed to be in the public domain. This distinction was given legislative expression in both Ireland and Britain by their respective nineteenth century public records Acts, which preserved and rendered available to the public legal and court records, but which did not extend to the records of secretaries of state or government ministers. (1) Irish state papers are the accumulated documents received or created by the offices of state which, until the termination of direct rule of Ireland by England in 1922, composed the Irish executive, headed by the chief governor of Ireland, and included the Privy Seal Office, the Privy Council Office and the Chief Secretary's Office. -

Government of Ireland Act, 1920. 10 & 11 Geo

?714 Government of Ireland Act, 1920. 10 & 11 GEo. 5. CH. 67.] To be returned to HMSO PC12C1 for Controller's Library Run No. E.1. Bin No. 0-5 01 Box No. Year. RANGEMENT OF SECTIONS. A.D. 1920. IUD - ESTABLISHMENT OF PARLIAMENTS FOR SOUTHERN IRELAND. AND NORTHERN IRELAND AND A COUNCIL OF IRELAND. Section. 1. Establishment of Parliaments of Southern and Northern Ireland. 2. Constitution of Council of Ireland. POWER TO ESTABLISH A PARLIAMENT FOR THE WHOLE OF IRELAND. Power to establish a Parliament for the whole of Ireland. LEGISLATIVE POWERS. 4. ,,.Legislative powers of Irish Parliaments. 5. Prohibition of -laws interfering with religious equality, taking property without compensation, &c. '6. Conflict of laws. 7. Powers of Council of Ireland to make orders respecting private Bill legislation for whole of Ireland. EXECUTIVE AUTHORITY. S. Executive powers. '.9. Reserved matters. 10. Powers of Council of Ireland. PROVISIONS AS TO PARLIAMENTS OF SOUTHERN AND NORTHERN IRELAND. 11. Summoning, &c., of Parliaments. 12. Royal assent to Bills. 13. Constitution of Senates. 14. Constitution of the Parliaments. 15. Application of election laws. a i [CH. 67.1 Government of Ireland Act, 1920, [10 & 11 CEo. A.D. 1920. Section. 16. Money Bills. 17. Disagreement between two Houses of Parliament of Southern Ireland or Parliament of Northern Ireland. LS. Privileges, qualifications, &c. of members of the Parlia- ments. IRISH REPRESENTATION IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS. ,19. Representation of Ireland in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. FINANCIAL PROVISIONS. 20. Establishment of Southern and Northern Irish Exchequers. 21. Powers of taxation. 22. -

Elizabeth I and Irish Rule: Causations For

ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 By KATIE ELIZABETH SKELTON Bachelor of Arts in History Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2009 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2012 ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 Thesis Approved: Dr. Jason Lavery Thesis Adviser Dr. Kristen Burkholder Dr. L.G. Moses Dr. Sheryl A. Tucker Dean of the Graduate College ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 1 II. ENGLISH RULE OF IRELAND ...................................................... 17 III. ENGLAND’S ECONOMIC RELATIONSHIP WITH IRELAND ...................... 35 IV. ENGLISH ETHNIC BIAS AGAINST THE IRISH ................................... 45 V. ENGLISH FOREIGN POLICY & IRELAND ......................................... 63 VI. CONCLUSION ...................................................................... 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................ 94 iii LIST OF MAPS Map Page The Island of Ireland, 1450 ......................................................... 22 Plantations in Ireland, 1550 – 1610................................................ 72 Europe, 1648 ......................................................................... 75 iv LIST OF TABLES Table Page -

From Munster to La Coruña Across the Celtic Sea: Emigration, Assimilation, and Acculturation in the Kingdom of Galicia (1601-40)

Obradoiro de Historia Moderna, N.º 19, 9-38, 2010, ISSN: 1133-0481 FROM MUNSTER TO LA CORUÑA ACROSS THE CELTIC SEA: EMIGRATION, ASSIMILATION, AND AccULTURATION IN THE KINGDOM OF GALICIA (1601-40) Ciaran O’Scea University College Dublin RESUMEN . Entre 1602 y 1608 cerca de 10.000 individuos de todos los estratos de la sociedad gaélica irlandesa predominante en el suroeste de Irlanda emigraron al noroeste de España como consecuenciade la fallida intervención militar española en Kinsale en 1601-02, lo que condujo a la consolidación de la comunidad irlandesa en La Coruña (Galicia). Esto ha permitido un análisis de la asimilación e integración de la comunidad en las estructuras civiles, eclesiásticas y reales de Galicia y de la monarquía hispánica. Los resultados muestran como la inicial introspección de la comunidad irlandesa durante la primera década dio paso a una rápida asimilación e integración en la siguiente. Al mismo tiempo, las alteradas circunstancias socio-económicas y políticas condujeron a cambios de gran alcance en las estructuras internas y los valores socio-culturales de la comunidad. Palabras clave: emigración irlandesa, España, Irlanda, Galicia, La Coruña, asimilación, integración, Kinsale. ABSTR A CT . Between 1602 and 1608 c. 10.000 individuals from all strata of predominantly Gaelic Irish society in the south west of Ireland emigrated to the north west of Spain in the aftermath of the failed Spanish military intervention at Kinsale in 1601-02, leading to the consolidation of the fledling Irish community in La Coruña in Galicia. This has permitted an analysis of the community´s assimilation and integration to the civil, ecclesiastical and royal structures of Galicia and the Spanish monarchy. -

List of Manuscript and Printed Sources Current Marks and Abreviations

1 1 LIST OF MANUSCRIPT AND PRINTED SOURCES CURRENT MARKS AND ABREVIATIONS * * surrounds insertions by me * * variant forms of the lemmata for finding ** (trailing at end of article) wholly new article inserted by me + + surrounds insertion from the addenda ++ (trailing at end of article) wholly new article inserted from addenda † † marks what is (I believe) certainly wrong !? marks an unidentified source reference [ro] Hogan’s Ro [=reference omitted] {1} etc. different places but within a single entry are thus marked Identical lemmata are numbered. This is merely to separate the lemmata for reference and cross- reference. It does not imply that the lemmata always refer to separate names SOURCES Unidentified sources are listed here and marked in the text (!?). Most are not important but they are nuisance. Identifications please. 23 N 10 Dublin, RIA, 967 olim 23 N 10, antea Betham, 145; vellum and paper; s. xvi (AD 1575); see now R. I. Best (ed), MS. 23 N 10 (formerly Betham 145) in the Library of the RIA, Facsimiles in Collotype of Irish Manuscript, 6 (Dublin 1954) 23 P 3 Dublin, RIA, 1242 olim 23 P 3; s. xv [little excerption] AASS Acta Sanctorum … a Sociis Bollandianis (Antwerp, Paris, & Brussels, 1643—) [Onomasticon volume numbers belong uniquely to the binding of the Jesuits’ copy of AASS in their house in Leeson St, Dublin, and do not appear in the series]; see introduction Ac. unidentified source Acallam (ed. Stokes) Whitley Stokes (ed. & tr.), Acallam na senórach, in Whitley Stokes & Ernst Windisch (ed), Irische Texte, 4th ser., 1 (Leipzig, 1900) [index]; see also Standish H.