Winning Combination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muhammad Ali: an Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America

Muhammad Ali: An Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Voulgaris, Panos J. 2016. Muhammad Ali: An Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33797384 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Muhammad Ali: An Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America Panos J. Voulgaris A Thesis in the Field of History for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2016 © November 2016, Panos John Voulgaris Abstract The rhetoric and life of Muhammad Ali greatly influenced the advancement of African Americans. How did the words of Ali impact the development of black America in the twentieth century? What role does Ali hold in history? Ali was a supremely talented artist in the boxing ring, but he was also acutely aware of his cultural significance. The essential question that must be answered is how Ali went from being one of the most reviled people in white America to an icon of humanitarianism for all people. He sought knowledge through personal experience and human interaction and was profoundly influenced by his own upbringing in the throes of Louisville’s Jim Crow segregation. -

The Epic 1975 Boxing Match Between Muhammad Ali and Smokin' Joe

D o c u men t : 1 00 8 CC MUHAMMAD ALI - RVUSJ The epic 1975 boxing match between Muhammad Ali and Smokin’ Joe Frazier – the Thriller in Manila – was -1- 0 famously brutal both inside and outside the ring, as a neW 911 documentary shows. Neither man truly recovered, and nor 0 did their friendship. At 64, Frazier shows no signs of forgetting 8- A – but can he ever forgive? 00 8 WORDS ADAM HIGGINBOTHAM PORTRAIT STEFAN RUIZ C - XX COLD AND DARK,THE BIG BUILDING ON of the world, like that of Ali – born Cassius Clay .pdf North Broad Street in Philadelphia is closed now, the in Kentucky – began in the segregated heartland battered blue canvas ring inside empty and unused of the Deep South. Born in 1944, Frazier grew ; for the first time in more than 40 years. On the up on 10 acres of unyielding farmland in rural Pa outside, the boxing glove motifs and the black letters South Carolina, the 11th of 12 children raised in ge that spell out the words ‘Joe Frazier’s Gym’ in cast a six-room house with a tin roof and no running : concrete are partly covered by a ‘For Sale’ banner. water.As a boy, he played dice and cards and taught 1 ‘It’s shut down,’ Frazier tells me,‘and I’m going himself to box, dreaming of being the next Joe ; T to sell it.The highest bidder’s got it.’The gym is Louis. In 1961, at 17, he moved to Philadelphia. r where Frazier trained before becoming World Frazier was taken in by an aunt, and talked im Heavyweight Champion in 1970; later, it would also his way into a job at Cross Brothers, a kosher s be his home: for 23 years he lived alone, upstairs, in slaughterhouse.There, he worked on the killing i z a three-storey loft apartment. -

Sample Download

What they said about Thomas Myler’s previous books New York Fight Nights Thomas Myler has served up another collection of gripping boxing stories. The author packs such a punch with his masterful storytelling that you will feel you were ringside inhaling the sizzling atmosphere at each clash of the titans. A must for boxing fans. Ireland’s Own There are few more authoritative voices in boxing than Thomas Myler and this is another wonderfully evocative addition to his growing body of work. Irish Independent Another great book from the pen of the prolific Thomas Myler. RTE, Ireland’s national broadcaster The Mad and the Bad Another storytelling gem from Thomas Myler, pouring light into the shadows surrounding some of boxing’s most colourful characters. Irish Independent The best boxing book of the year from a top writer. Daily Mail Boxing’s Greatest Upsets: Fights That Shook The World A respected writer, Myler has compiled a worthy volume on the most sensational and talked-about upsets of the glove era, drawing on interviews, archive footage and worldwide contacts. Yorkshire Evening Post Fight fans will glory in this offbeat history of boxing’s biggest shocks, from Gentleman Jim’s knockout of John L. Sullivan in 1892 to the modern era. A must for your bookshelf. Hull Daily Mail Boxing’s Hall of Shame Boxing scribe Thomas Myler shares with the reader a ringside seat for the sport’s most controversial fights. It’s an engaging read, one that feeds our fascination with the darker side of the sport. Bert Sugar, US author and broadcaster Well written and thoroughly researched by one of the best boxing writers in these islands, Myler has a keen eye for the story behind the story. -

6 Diciembre 2015 Ingles.Cdr

THE DOORS TO LATIN AMERICA, arrival of the Spanish on the XVI Century. TIJUANA B.C. , HOST VENUE OF January 2016 will be an spectacular year, the second World Boxing Council female OUR NEXT FEMALE CONVENTION convention will be hosted on this magnificent place. “Here starts our homeland” that’s Tijuana´s motto, it is the first Latin America city that The greatest female fighters will travel to shares border with San Diega, US anf is the Tijuana with the main goal of spreading and fifth most populated city of Mexico having keep developing this sport as we are able to more than 1, 600,000 habitants on it. enjoy all of its cultural and historic attractions. Tijuana is a city of great commercial and cultural activity, its history began with the Editorial Index Future fights WBC Emerald Belt May-Pac Roman Gonzalez Golovkin Viktor Postol Jorge Linares Zulina Muñoz Mikaela Lauren Erica Farias Alicia Ashley Ibeth Zamora Yessica Chavez Soledad Matthysse Leo Santa Cruz becomes Diamond champion Francisco Vargas Directorio: Saul Alvarez “WBC Boxing World” is the official magazine of the World Boxing Council. Floyd´s final Hurrah . Executive Director WBC Cares Mauricio Sulaimán. WBC Annual Convention Subdirector Víctor Silva. Knowing a Champion: Deontay Wilder Marketing Manager José Antonio Arreola Sulaimán Muhammad Ali Honored Managing Editor Mauricio Sulaiman is presented with the keys to the Francisco Posada Toledo city of Miami Traducción PRESIDENT DANIEL ORTEGA: a great supporter of Paul Landeros / James Blears Nicaraguan boxing Design Director Alaín -

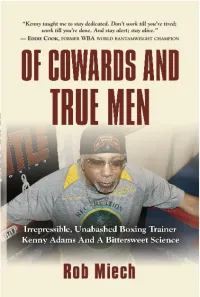

Of Cowards and True Men Order the Complete Book From

Kenny Adams survived on profanity and pugilism, turning Fort Hood into the premier military boxing outfit and coaching the controversial 1988 U.S. Olympic boxing team in South Korea. Twenty-six of his pros have won world-title belts. His amateur and professional successes are nonpareil. Here is the unapologetic and unflinching life of an American fable, and the crude, raw, and vulgar world in which he has flourished. Of Cowards and True Men Order the complete book from Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/8941.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Enjoy your free excerpt below! Of Cowards and True Men Rob Miech Copyright © 2015 Rob Miech ISBN: 978-1-63490-907-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., Bradenton, Florida, U.S.A. Printed on acid-free paper. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2015 First Edition I URINE SPRAYS ALL over the black canvas. A fully loaded Italian Galesi-Brescia 6.35 pearl-handled .25-caliber pistol tumbles onto the floor of the boxing ring. Just another day in the office for Kenny Adams. Enter the accomplished trainer’s domain and expect anything. “With Kenny, you never know,” says a longtime colleague who was there the day of Kenny’s twin chagrins. First off, there’s the favorite word. Four perfectly balanced syllables, the sweet matronly beginning hammered by the sour, vulgar punctuation. -

The 7 Leader Questions

Leader Tactical Questions for Leaders to Ask Before, During, and After Operations The Questions 7 Foreword by Teddy Kleisner, Colonel, U.S. Army Thomas E. Meyer A Publication of The Company Leader The Company Leader is a Proud Member of The Military Writers Guild Printing Instructions: This document formats to print on 5x8 (A5) printer paper. If you print on 8.5 x 11 (Standard) paper, you will have an additional 3 inches of margin space around the document. This may be optimal if you are a note-taker. You can also elect to print on 8.5 x 11 paper and click the printer option to the effect of “fit to paper” which will enlarge the document to fill the paper space. Cover Photo Credit: Soldiers begin the movement phase during a combined arms live-fire exercise at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, August 9, 2018. The exercise is part of an overall training progression to maintain combat readiness for the 21st Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Brigade Combat Team, 25th Infantry Division, in preparation for a Joint Readiness Training Center rotation later this year. (U.S. Army photo by 1st Lt. Ryan DeBooy) Leader The Questions 7 Tactical Questions for Leaders to Ask Before, During, and After Operations By Thomas E. Meyer Foreword by Teddy Kleisner, Col., U.S. Army This is a publication of The Company Leader. A free digital version of this document is available after subscribing to the website at http://companyleader.themilitaryleader.com . ©2019 The Company Leader This project is dedicated to the soldiers, non-commissioned officers, and officers of the 23rd Infantry Regiment–past and present, but specifically circa 2015-2017. -

The Sweet Science by Trainers Such As George Benton, He Was Able to Learn Boxing Tactics and Knowledge That Are Unfortunately Becoming Harder to Find As Time Passes

SECTION IV: PUNCHING BASICS 27 The Jab 28 PREFACE The Power Punch iv Straight Right (Rear Hand) Punch 30 WHY THIS BOOK? Left (Lead Hand) Hook 32 v The Uppercut SECTION I: BECOMING A COLLEGE BOXER 35 2 SECTION V: COMBINATION PUNCHING Sportsmanship 39 2 SECTION VI: DISTANCE APPRECIATION The Importance of Physical Conditioning 43 3 SECTION VII: DEFENSE SECTION II: STANCE 46 11 Using the Hands Foot Position Blocks and Parries 12 47 Trunk Position Evasive Action from the Waist 13 Ducking and Slipping 48 Head and Hand Position 15 Defensive Footwork Breaking Ground and Side Steps SECTION III: FOOtwORK 49 20 SECTION VIII: SPARRING Advancing 51 21 ABOUT USIBA Retreating 53 21 Lateral Movement ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 22 54 Pivoting REFERENCE MATERIAL 23 55 Before I could read, I started boxing lessons under the tutelage of my uncle, Pete Hobbie. This book is dedicated to him and his trainer, Wilson Pitts. It is a compilation of all that I have learned throughout my eighteen years of boxing training combined along with techniques from both men. Wilson not only taught and trained Peter Hobbie, but also the boxing pride of Richmond, Virginia, Carl “Piggy” Hutchins. Wilson lived in Philadelphia and studied boxing at Joe Frazier’s gym in the 1970s. It was there that he learned and embraced the techniques of the legendary trainer Eddie Futch. By watching and eventually being accepted as a student of the sweet science by trainers such as George Benton, he was able to learn boxing tactics and knowledge that are unfortunately becoming harder to find as time passes. -

NM-16-Negotiations and Professional Boxing.Indd

a 16 b Negotiation and Professional Boxing Habib Chamoun-Nicolas, Randy D. Hazlett, Russell Mora, Gilberto Mendoza & Michael L. Welsh* Editors’ Note: In this groundbreaking piece, a group of authors with unimpeachable expertise in one of the least likely environments ever considered for negotiation analyze what is actually going on in the professional boxing ring. Their surprising conclusions take the facile claim of our field that “everybody negotiates” to a whole new level. Not only does this chapter serve as a kind of extreme-case demonstration of why students should consider learning negotiation to be central to any occupation they may take up in future; it might well serve as inspira- tion for some new studies in other fields in which negotiation may previously have been thought irrelevant. Introduction Referee Judge Mills Lane, a former marine and decorated fighter in his day, was blindsided. Mills, a late substitution due to an objection from the Tyson camp, issued an early blanket warning to keep punch- es up. According to our own analysis of the fight video (Boxingsociety. com 1997), defending heavyweight champion Evander Holyfield gained an early advantage with a characteristic forward lunging style. Following a punch, Holyfield would lock up with the smaller Mike Tyson, shoulder-to-shoulder, applying force throughout. Holyfield fin- ished the round clearly in the lead. At the 2:28 mark in the second, a * Habib Chamoun-Nicolas is an honorary professor at Catholic University of Santiago Gua yaquil-Ecuador and an adjunct professor and member of the ex- ecutive board at the Cameron School of Business at University of St. -

Backup of 5 Noviembre 2015 Ingles.Cdr

Editorial Yunnan Impression Show Index Future fights Linares will continue in the Lightweight division Andrzej Fonfara defeats Nathan Cleverly in a pummel war "Chocolatito" melts Brian Golovkin TKO´s Lemieux Viktor Postol, New Superlight World Champion WBC Cares in Kunming, China Kunming World Convention Knowing a Champion: Leo Santa Cruz The magic of a Convention Is Callum Smith The One? 1990 Chávez vs Taylor The Clowning Glory The WBC unites with Mexico City to combat breastcancer Muhammad Ali honored at fortieth Anniversary of Directorio: the Thrilla in Manila “WBC Boxing World” is the official Dodge that! "Great balls of fire" hurled by Cotto magazine of the World Boxing Council. "Macho" Camacho, a candidate for International Executive Director Boxing Hall of Fame Mauricio Sulaimán. Great Year for women´s boxing Subdirector Víctor Silva. World Champions Marketing Manager José Antonio Arreola Sulaimán Managing Editor Francisco Posada Toledo Traducción Paul Landeros / James Blears Design Director Alaín M. Flores Photos Naoki Fukuda Sumio Yamada Alma Montiel José Rodríguez Contributing Editors Víctor Cota (WBC Historian) José Antonio Arreola Sulaiman Juan Pereira James Blears Jamie Parry and Robbie Oliver Santa Cruz Paulina Brindis Our newest diamond Champion Dear Friends. The most important event of the WBC has taken place. Our annual Convetion in Kunming China, was a great and memorable success. Regarding ring activity, Jorge Linares, Roman Gonzalez and Gennady Golovkin defended their respective crowns with style, and also a new name is included in the WBC chárter of champions...Viktor Postol . In this edition of the magazine you will learn more of these hard hitting developments. -

Sub-Group Autographs

Subgroup XVI. Autographs Series 1. Single Autographs Box 1 (binder) Divider 1. Singles / Sammy Angott, Vito Antuofermo, Bob Arum, Alexis Arguello Divider 2. Singles / Billy Bachus, Iran Barkley, Carmen Basilio (Christy Martin), Roberto Benitez, Wilfredo Benitez Divider 3. Singles / Nino Benvenutto, Trevor Berbick, Riddick Bowe, Joe Brown, Simon Brown, Ken Buchanan, Michael Buffer, Chris Byrd Divider 4. Singles / Teddy Brenner (Irving Cohen), Prudencio Cardona, Bobby Chacon, Don Chargin, George Chuvalo, Curtis Cokes, Young Corbett III (Mushy Callahan), Reginaldo Curiel, Gil Clancy Divider 5. Singles / Robert Daniels, Tony DeMarco, Roberto Duran, James Douglas, Don Dunphy Box 2 (binder) Divider 1. Singles / Cornelius Boza Edwards, Jimmy Ellis, Florentino Fernandez, George Foreman, Vernon Forest, Bob Foster Divider 2. Singles / Don Fraser, Joe Frazier, Gene Fullmer (Carmen Basilio, Joey Giardello), Jay & Don Fullmer Divider 3. Singles / Khaosai Galaxy, Joey Gamache, Arturo Gatti, Harold Gomes, Joey Giardello, Wilfredo Gomez, Emile Griffith, Toby Gibson (referee) Divider 4. Singles / Marvin Hagler, Demetrius Hopkins, Julian Jackson, Lew Jenkins, Eder Jofre, Harold Johnson, Glen Johnson, Jack Johnson, Ingomar Johansson, Al Jones Box 3 (binder) Divider 1. Singles / Issy Kline (Mrs. Max Baer, Buddy Baer), Ismael Laguna, Jake LaMotta, Juan LaPorta, Sugar Ray Leonard, Nicolino Loche, Danny Lopez, Tommy Lougran, Joe Louis, Ron Lyle Divider 2. Singles / Paul Malignaggi, Joe Maxim, Mike McCallum, Babs McCarthy, Buddy McGirt, Juan McPherson, Arthur Mercante, Nate Miller, Alan Minter, Willie Monroe, Archie Moore, Matthew Saad Muhammad, Kid Murphy Divider 3. Singles / Jose Napoles, Terry Norris, Ken Norton, Michael Nunn Divider 4. Singles / Packey O’Gatty, Sean O’Grady, Rubin Olivares, Bobo Olson, Carlos Ortiz Box 4 (binder) Divider 1. -

Strong Group of Mexican-Americans Carries on Enduring Tradition

LETTERS FROM EUROPE FROCH-KESSLER IS A COMPELLING REMATCH STRONG GROUP OF MEXICAN-AMERICANS CARRIES ON ENDURING TRADITION VICTOR ORTIZ ROBERT GUERRERO LEO SANTA CRUZ UNHAPPY RETURNS BOXERS OFTEN HAVE A TOUGH TIME STAYING RETIRED FATHER-SON ACT ANGEL GARCIA FIRES OFF WORDS, SON DANNY PUNCHES HOMECOMING MAY 2013 MAY SERGIO MARTINEZ RETURNS TO ARGENTINA A HERO TOO YOUNG TO DIE $8.95 OMAR HENRY NEVER HAD A CHANCE TO BLOSSOM CONTENTS / MAY 2013 38 64 70 FEATURES COVER STORY PACKAGE 58 | OVERSTAYED WELCOMES 76 | A LIFE CUT SHORT BOXERS HAVE A SELF-DESTRUCTIVE OMAR HENRY DIED OF CANCER BEFORE 38 | ENDURING TRADITION HABIT OF STICKING AROUND TOO LONG HE COULD REALIZE HIS POTENTIAL MEXICAN-AMERICAN BOXERS’ RECORD By Bernard Fernandez By Gary Andrew Poole OF SUCCESS CONTINUES By Don Stradley 64 | BARK AND BITE 82 | UNTAPPED SOURCE? ANGEL AND DANNY GARCIA ARE AN OLYMPIC CHAMPION 46 | NEW SHERIFF IN TOWN EFFECTIVE FATHER-SON TEAM ZOU SHIMING COULD MIKEY GARCIA’S BLEND OF POWER, By Ron Borges BE THE FIRST STAR SAVVY IS PROVING FORMIDABLE FROM CHINA 7O WELCOME HOME By Norm Frauenheim | By Tim Smith SERGIO MARTINEZ RETURNS TO 52 | BEST IN THE BIZ ARGENTINA A CONQUERING HERO TOP 10 MEXICAN-AMERICAN BOXERS By Bart Barry By Doug Fischer AT RINGTV.COM DEPARTMENTS 4 | RINGSIDE 94 | RINGSIDE REPORTS 5 | OPENING SHOTS 100 | WORLDWIDE RESULTS 10 | COME OUT WRITING 102 | COMING UP 11 | READY TO GRUMBLE 104 | NEW FACES: TERENCE CRAWFORD By David Greisman By Mike Coppinger 15 | ROLL WITH THE PUNCHES 106 | SIX PACK Jabs and Straight Writes by Thomas Hauser By T.K. -

8 Sports CFP 11-9-11.Indd

FREE PRE ss Page 8 Colby Free Press Wednesday, November 9, 2011 SSPORTPORT SS Trojan men ready Taking it to the mat to race at nationals By Kayla Cornett Ortiz said his team has a good nity College was ranked No. 21 Colby Free Press chance at nationals considering and is now No. 25 and Hutchinson [email protected] Colby’s regional finish. Community College was No. 22 “I really think we’re gonna do last week, but it dropped out of the The Colby Community College fine,” he said. “As bad as our re- top 25 for week 9. The rest of the men’s cross country team is ready gion meet was, we barely got beat teams competing are unranked. to compete with its best seven run- by Johnson County, now the No. Ortiz said he is not too worried ners at the National Junior College 4 team.” about having dropped in the rank- Athletic Association Cross Coun- The national rankings for week ings this week. try Championships on Saturday in nine came out Tuesday, and many “Having a bad day and still be- Hobbs, N.M. of the teams competing at nation- ing in the top 10, I think that says “We’re excited about it,” Head als, including Colby, are in a dif- a lot about our team,” he said. “We Coach James Ortiz said. “I think ferent spot. just gotta hope for a normal day. the guys are ready to reedem them- Garden City was ranked No. 1 That’s the hard thing about junior selves after a bad region meet.” last week, but dropped to the No.