NM-16-Negotiations and Professional Boxing.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fight Night Round 3 (Xbox 360)

Fight Night RouNd 3 (XboX 360) WARNING Complete CoNtRols Block, punch, and dance around the ring in your pursuit of the world title by using Before playing this game, read the Xbox 360 Instruction Manual and any EA SPORTS™ Fight Night Round 3’s innovative control system. peripheral manuals for important safety and health information. Keep all manuals for future reference. For replacement manuals, see www.xbox.com/ geNeRal gameplay support or call Xbox Customer Support (see inside of back cover). Pause game Lean/Body punch Parry/Block Important Health Warning About Playing Switch stance Signature punch Video Games Clinch Camera relative Illegal blow movement Photosensitive Seizures Signature punch A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed Taunt to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive Total Punch Control epileptic seizures” while watching video games. (see below) These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, Note: To parry/block, pull and hold ^ + move C. altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, Note: To lean, pull and hold ] + move L. disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from total punch CoNtRol falling down or striking nearby objects. With Total Punch Control, you direct every movement your boxer makes in the ring. Whether Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of attacking the body with a straight right or sneaking in a left hook before the bell, determine these symptoms. -

Dec 2004 Current List

Fighter Opponent Result / RoundsUnless specifiedDate fights / Time are not ESPN NetworkClassic, Superbouts. Comments Ali Al "Blue" Lewis TKO 11 Superbouts Ali fights his old sparring partner Ali Alfredo Evangelista W 15 Post-fight footage - Ali not in great shape Ali Archie Moore TKO 4 10 min Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 ABC Commentary by Cossell - Some break up in picture Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 British CC Ali gets cut Ali Brian London TKO 3 B&W Ali in his prime Ali Buster Mathis W 12 Commentary by Cossell - post-fight footage Ali Chuck Wepner KO 15 Classic Sports Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 B&W Commentary by Don Dunphy - Ali in his prime Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 Classic Sports Ali in his prime Ali Doug Jones W 10 Jones knows how to fight - a tough test for Cassius Ali Earnie Shavers W 15 Brutal battle - Shavers rocks Ali with right hand bombs Ali Ernie Terrell W 15 Feb, 1967 Classic Sports Commentary by Cossell Ali Floyd Patterson i TKO 12 22-Nov-1965 B&W Ali tortures Floyd Ali Floyd Patterson ii TKO 7 Superbouts Commentary by Cossell Ali George Chuvalo i W 15 Classic Sports Ali has his hands full with legendary tough Canadian Ali George Chuvalo ii W 12 Superbouts In shape Ali battles in shape Chuvalo Ali George Foreman KO 8 Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Gorilla Monsoon Wrestling Ali having fun Ali Henry Cooper i TKO 5 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Henry Cooper ii TKO 6 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only - extensive pre-fight Ali Ingemar Johansson Sparring 5 min B&W Silent audio - Sparring footage Ali Jean Pierre Coopman KO 5 Rumor has it happy Pierre drank before the bout Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 Superbouts Ali at his relaxed best Ali Jerry Quarry i TKO 3 Ali cuts up Quarry Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jimmy Ellis TKO 12 Ali beats his old friend and sparring partner Ali Jimmy Young W 15 Ali is out of shape and gets a surprise from Young Ali Joe Bugner i W 12 Incomplete - Missing Rds. -

George Hackenschmidt Vs. Frank Gotch Media Representations and the World Wrestling Title of 1908 Kim Beckwith & Jan Todd the University of Texas

Iron Game History Volume 11 Number 2 George Hackenschmidt vs. Frank Gotch Media Representations and the World Wrestling Title of 1908 Kim Beckwith & Jan Todd The University of Texas International wrestling star, George Hacken- stories about and a constituent of that world, an element schmidt, widely known as "The Russian Lion," met the of the story." The reporter, they argue, "not only relates American champion, Frank Gotch, at Chicago's Dexter stories but makes them."2 Similarly, pop culture analyst Park Amphitheater on April 3, 1908, in a wrestling title Carlin Romano contends that journalism is not a "minor bout that was labeled "The Athletic Contest of the Cen- placed before reality," but a "coherent nanative of the tmy" on the cover of the match program.' After three world that serves a particular purpose."3 Thinking about preliminary bouts, the much anticipated World's Heavy- journalism in light of this definition makes it easier to weight Wrestling Championships in the catch-as-catch- understand how in the days following the historic Gotch can style began at approximately 10:30 P.M. More than Hackenschmidt bout such different tales would be told two hours later, reporters ...-------------------. by various journalists even scrambled to file their stories in though all of them had watched the early hours of the morning SOUVENIR PROGRAM the same spmting event. Like and share their ringside intelli- 'f the characters in John Godfrey gence with an anxiously await- The Athletic Contest of Saxes's poem, "The Blind Men ing nation and world. The news the Century and the Elephant," almost all they sent out from Chicago, _ For •h• _ of the reporters who pe1111ed however, was totally unexpect- WORLD'S WRESTLING their reports from Chicago had ed. -

From the Ground up the First Fifty Years of Mccain Foods

CHAPTER TITLE i From the Ground up the FirSt FiFty yearS oF mcCain FoodS daniel StoFFman In collaboratI on wI th t ony van l eersum ii FROM THE GROUND UP CHAPTER TITLE iii ContentS Produced on the occasion of its 50th anniversary Copyright © McCain Foods Limited 2007 Foreword by Wallace McCain / x by All rights reserved. No part of this book, including images, illustrations, photographs, mcCain FoodS limited logos, text, etc. may be reproduced, modified, copied or transmitted in any form or used BCE Place for commercial purposes without the prior written permission of McCain Foods Limited, Preface by Janice Wismer / xii 181 Bay Street, Suite 3600 or, in the case of reprographic copying, a license from Access Copyright, the Canadian Toronto, Ontario, Canada Copyright Licensing Agency, One Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario, M6B 3A9. M5J 2T3 Chapter One the beGinninG / 1 www.mccain.com 416-955-1700 LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Stoffman, Daniel Chapter Two CroSSinG the atlantiC / 39 From the ground up : the first fifty years of McCain Foods / Daniel Stoffman For copies of this book, please contact: in collaboration with Tony van Leersum. McCain Foods Limited, Chapter Three aCroSS the Channel / 69 Director, Communications, Includes index. at [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-9783720-0-2 Chapter Four down under / 103 or at the address above 1. McCain Foods Limited – History. 2. McCain, Wallace, 1930– . 3. McCain, H. Harrison, 1927–2004. I. Van Leersum, Tony, 1935– . II. McCain Foods Limited Chapter Five the home Front / 125 This book was printed on paper containing III. -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04Rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O. BOX 377 JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (ARGENTINA) MARACAY 2101 -A ALAN KIM (KOREA) EDO. ARAGUA - VENEZUELA SHIGERU KOJIMA (JAPAN) PHONE: + (58-244) 663-1584 VICE CHAIRMAN GONZALO LOPEZ SILVERO (USA) + (58-244) 663-3347 GEORGE MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] MEDIA ADVISORS FAX: + (58-244) 663-3177 E-mail: [email protected] SEBASTIAN CONTURSI (ARGENTINA) Web site: www.wbaonline.com UNIFIED CHAMPION: JEAN MARC MORMECK FRA World Champion: JOHN RUIZ USA Won Title: 04-02-05 World Champion: FABRICE TIOZZO FRA Won Title: 12-13 -03 Last Defense: Won Title: 03-20- 04 Last Mandatory: 04-30 -05 _________________________________ Last Mandatory: 02-26- 05 Last Defense: 04-30 -05 World C hampion: VACANT Last Defense: 02-26- 05 WBC: VITALI KLITSCHKO - IBF: CHRIS BYRD WBC: JEAN MARC MORMECK- IBF: O’NEIL BELL WBC: THOMAS ADAMEK - IBF: CLINTON WOODS WBO : LAMON BREWSTER WBO : JOHNNY NELSON WBO : ZSOLT ERDEI 1. NICOLAY VALUEV (OC) RUS 1. VALERY BRUDOV RUS 1. JORGE CASTRO (LAC) ARG 2. NOT RATED 2. VIRGIL HILL USA 2. SILVIO BRANCO (OC) ITA 3. WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO UKR 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 3. GUILLERMO JONES (0C) PAN 3. MANNY SIACA (LAC-INTERIM) P.R. ( Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 4. RAY AUSTIN (LAC) USA 4. STEVE CUNNINGHAM USA (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) 4. GLEN JOHNSON USA ( 5. CALVIN BROCK USA 5. LUIS PINEDA (LAC) PAN 5. PIETRO AURINO ITA l 6. -

My Fighting Life

MY MY FIGHTING LIFE Photo: Hana Studios, Ltd. _/^ My Fighting Life BY GEORGES GARPENTIER (Champion Heavy-wight Boxer of With Eleven Illustrations CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1920 To All British Sportsmen I dedicate this, The Story of My Life. Were I of their own great country, I feel I could have no surer, no warmer, no more lasting place in their friendship CONTENTS CHAPTBX FAGB 1. I BECOME DESCAMPS' PUPIL ... 1 2. To PARIS 21 3. MY PROFESSIONAL CAREER BEGINS . 30 4. I Box IN ENGLAND ..... 47 5. MY FIGHTS WITH LEDOUX, LEWIS, SULLIVAN AND OTHERS ..... 51 6. I MEET THE ILLINOIS THUNDERBOLT . 68 7. MY FIGHTS WITH WELLS AND A SEQUEL . 79 8. FIGHTS IN 1914 99 9. THE GREAT WAR : I BECOME A FLYING MAN 118 10. MILITARY BOXING ..... 133 11. ARRANGING THE BECKETT FIGHT . 141 12. THE GREAT FIGHT 150 13. PSYCHOLOGY AND BOXING . 158 14. How I TRAINED TO MEET BECKETT . 170 15. THE FUTURE OF BOXING : TRAINING HINTS AND SECRETS . .191 16. A CHAPTER ON FRA^OIS DESCAMPS . 199 17. MEN I HAVE FOUGHT .... 225 ILLUSTRATIONS GEORGES CARPENTIER .... Frontispiece FACING PAGE 1. CARPENTIER AT THE AGE OF TWELVE . 10 CARPENTIER AT THE AGE OF THIRTEEN . 10 2. CARPENTIER (WHEN ELEVEN) WITH DESCAMPS . 24 CARPENTIER AND LEDOUX . .24 3. M. DESCAMPS ...... 66 4. CARPENTIER WHEN AN AIRMAN . .180 5. CARPENTIER AT THE AGE OF SEVENTEEN . 168 CARPENTIER TO-DAY . .. .168 6. CARPENTIER IN FIGHTING TRIM . 226 7. M. AND Mme. GEORGES CARPENTIER . 248 MY FIGHTING LIFE CHAPTER I I BECOME DESCAMPS' PUPIL OUTSIDE my home in Paris many thousands of my countrymen shouted and roared and screamed; women tossed nosegays and blew kisses up to my windows. -

“The Old Bush Telegraph”

NEWS FROM CLASSMATES “The Old Bush Telegraph” DOWNLANDS 1956 – 61 January 2016 Issue #53 David Bowden: David attended “The Mass” in January, but had to leave for his return to Roma before lunch. I contacted him to be sure he arrived home safely: “ We had a good trip home. Have to admit the trips are starting to take a toll on my old body. During week days I normally go to the Roma Poll at 5am and do exercises in the water for 30-40 minutes. I did not surface until 7am on Monday! Spoke to Garth Cocks at the Mass. Looks as though he may be getting me involved in writing Downlands history. I have an appointment in early February in Toowoomba so that may be our first meeting. Our Muckadilla Community 2015 Anzac Day A Happy and Healthy New Year to all Ceremony and play that I wrote on the enlistment of the Muckadilla First World War soldiers was nominated January has been and gone – where does the time for an Australia Day Award. Will have to see how we go?? go with that one! Thank you to the many among you who sent I’m hoping to take my book on the Muckadilla Service greetings for Christmas and the New Year. I hope I responded to all of you, if not, my Men and Women to the publisher soon. apologies. PS Rod Cochrane contacted me after the week-end In this edition: too. Much appreciated. David. News from Classmates [1 – 3] Bernie Casey: Very kindly used his skills with his Special Notice [3] camera on Mass Day. -

Online Newsletter Issue 13 October 2013

Online Newsletter Issue 13 October 2013 The IBRO online newsletter is an extension of the Quarterly IBRO Journal and contains material not included in the latest issue of the Journal. Newsletter Features 50 Years After Death, Ohio Honors Boxer Davey Moore by Mike Foley California Calling for Joey Giambra by Mike Casey Remembering A Forgotten Contender: Ibar Arrington by Steve Canton The Boxing Biographies Volume # 9: George “Kid” Lavigne by Rob Snell Book Recommendation: Muscle and Mayhem: The Saginaw Kid (Kid Lavigne) and The Fistic World of the 1890s by Lauren D. Chouinard. Book Review Tale of The “Kid” by Randi Bjornstad, The Register Guard Member inquiries, nostalgic articles, and obituaries submitted by several members. Special thanks to Mike Casey, Steve Canton, Henry Hascup, J.J. Johnston, Rick Kilmer, Harry Otty and Rob Snell, for their contributions to this issue of the newsletter. Keep Punching! Dan Cuoco International Boxing Research Organization Dan Cuoco Director, Editor and Publisher [email protected] All material appearing herein represents the views of the respective authors and not necessarily those of the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO). © 2013 IBRO (Original Material Only) CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS 3 Member Forum 5 IBRO Apparel 43 Final Bell FEATURES 6 50 Years After Death, Ohio Honors Boxer Davey Moore by Mike Foley 8 California Calling for Joey Giambra by Mike Casey 11 Remembering A Forgotten Contender: Ibar Arrington by Steve Canton 14 The Boxing Biographies Volume #9: George “Kid” Lavigne by Rob Snell BOOK RECOMMENDATIONS & REVIEWS 33 Muscle and Mayhem: The Saginaw Kid (Kid Lavigne) and The Fistic World of the 1890s by Lauren D. -

Critical Perspectives on the European Mediasphere

THE RESEARCHING AND TEACHING COMMUNICATION SERIES THE RESEARCHING AND TEACHING COMMUNICATION SERIES CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE EUROPEAN MEDIASPHERE THE INTELLECTUAL WORK OF THE 2011 ECREA EUROPEAN MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION DOCTORAL SUMMER SCHOOL Ljubljana, 2011 CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE EUROPEAN MEDIASPHERE. The Intellectual Work of the 2011 ECREA European Media and Communication Doctoral Summer School. Edited by: Ilija Tomanić Trivundža, Nico Carpentier, Hannu Nieminen, Pille Pruulmann-Venerfeldt, Richard Kilborn, Ebba Sundin and Tobias Olsson. Series: The Researching And Teaching Communication Series Series editors: Nico Carpentier and Pille Pruulmann-Venerfeldt Published by: Faculty of Social Sciences: Založba FDV For publisher: Hermina Krajnc Copyright © Authors 2011 All rights reserved. Reviewer: Mojca Pajnik Book cover: Ilija Tomanić Trivundža Design and layout: Vasja Lebarič Language editing: Kyrill Dissanayake Photographs: Ilija Tomanić Trivundža, François Heinderyckx, Andrea Davide Cuman, and Jeoffrey Gaspard. Printed by: Tiskarna Radovljica Print run: 400 copies Electronic version accessible at: http://www.researchingcommunication.eu The 2011 European Media and Communication Doctoral Summer School (Ljubljana, August 14-27) was supported by the Lifelong Learning Programme Erasmus Intensive Programme project (grant agreement reference number: 2010-7242), the University of Ljubljana – the Department of Media and Communication Studies and the Faculty of Social Sciences, a consortium of 22 universi- ties, and the Slovene Communication -

Muhammad Ali: an Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America

Muhammad Ali: An Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Voulgaris, Panos J. 2016. Muhammad Ali: An Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33797384 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Muhammad Ali: An Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America Panos J. Voulgaris A Thesis in the Field of History for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2016 © November 2016, Panos John Voulgaris Abstract The rhetoric and life of Muhammad Ali greatly influenced the advancement of African Americans. How did the words of Ali impact the development of black America in the twentieth century? What role does Ali hold in history? Ali was a supremely talented artist in the boxing ring, but he was also acutely aware of his cultural significance. The essential question that must be answered is how Ali went from being one of the most reviled people in white America to an icon of humanitarianism for all people. He sought knowledge through personal experience and human interaction and was profoundly influenced by his own upbringing in the throes of Louisville’s Jim Crow segregation. -

The Epic 1975 Boxing Match Between Muhammad Ali and Smokin' Joe

D o c u men t : 1 00 8 CC MUHAMMAD ALI - RVUSJ The epic 1975 boxing match between Muhammad Ali and Smokin’ Joe Frazier – the Thriller in Manila – was -1- 0 famously brutal both inside and outside the ring, as a neW 911 documentary shows. Neither man truly recovered, and nor 0 did their friendship. At 64, Frazier shows no signs of forgetting 8- A – but can he ever forgive? 00 8 WORDS ADAM HIGGINBOTHAM PORTRAIT STEFAN RUIZ C - XX COLD AND DARK,THE BIG BUILDING ON of the world, like that of Ali – born Cassius Clay .pdf North Broad Street in Philadelphia is closed now, the in Kentucky – began in the segregated heartland battered blue canvas ring inside empty and unused of the Deep South. Born in 1944, Frazier grew ; for the first time in more than 40 years. On the up on 10 acres of unyielding farmland in rural Pa outside, the boxing glove motifs and the black letters South Carolina, the 11th of 12 children raised in ge that spell out the words ‘Joe Frazier’s Gym’ in cast a six-room house with a tin roof and no running : concrete are partly covered by a ‘For Sale’ banner. water.As a boy, he played dice and cards and taught 1 ‘It’s shut down,’ Frazier tells me,‘and I’m going himself to box, dreaming of being the next Joe ; T to sell it.The highest bidder’s got it.’The gym is Louis. In 1961, at 17, he moved to Philadelphia. r where Frazier trained before becoming World Frazier was taken in by an aunt, and talked im Heavyweight Champion in 1970; later, it would also his way into a job at Cross Brothers, a kosher s be his home: for 23 years he lived alone, upstairs, in slaughterhouse.There, he worked on the killing i z a three-storey loft apartment. -

Boxing Edition

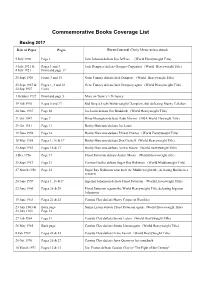

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson