From the Ground up the First Fifty Years of Mccain Foods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fight Night Round 3 (Xbox 360)

Fight Night RouNd 3 (XboX 360) WARNING Complete CoNtRols Block, punch, and dance around the ring in your pursuit of the world title by using Before playing this game, read the Xbox 360 Instruction Manual and any EA SPORTS™ Fight Night Round 3’s innovative control system. peripheral manuals for important safety and health information. Keep all manuals for future reference. For replacement manuals, see www.xbox.com/ geNeRal gameplay support or call Xbox Customer Support (see inside of back cover). Pause game Lean/Body punch Parry/Block Important Health Warning About Playing Switch stance Signature punch Video Games Clinch Camera relative Illegal blow movement Photosensitive Seizures Signature punch A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed Taunt to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive Total Punch Control epileptic seizures” while watching video games. (see below) These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, Note: To parry/block, pull and hold ^ + move C. altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, Note: To lean, pull and hold ] + move L. disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from total punch CoNtRol falling down or striking nearby objects. With Total Punch Control, you direct every movement your boxer makes in the ring. Whether Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of attacking the body with a straight right or sneaking in a left hook before the bell, determine these symptoms. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0259700 A1 Elling Et Al

US 2015025.9700A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0259700 A1 Elling et al. (43) Pub. Date: Sep. 17, 2015 (54) TRANSGENC PLANTS WITH RNA Publication Classification INTERFERENCE-MEDIATED RESISTANCE AGAINST ROOT-KNOT NEMATODES (51) Int. Cl. CI2N 5/82 (2006.01) (71) Applicant: WASHINGTON STATE CI2N IS/II3 (2006.01) UNIVERSITY, PULLMAN, WA (US) (52) U.S. Cl. CPC .......... CI2N 15/8285 (2013.01); C12N 15/I 13 (72) Inventors: Axel A. Elling, Pullman, WA (US); (2013.01); C12N 23 10/141 (2013.01); C12N Charles R. Brown, Pullman, WA (US) 2310/531 (2013.01) (21) Appl. No.: 14/626,070 (57) ABSTRACT Transgenic plants that are stably resistant to the nematode (22) Filed: Feb. 19, 2015 Meloidogyne Chitwoodi are provided, as are methods of mak ing such transgenic plants. The transgenic plants (such as Related U.S. Application Data potatoes) are genetically engineered to express interfering (60) Provisional application No. 61/948,761, filed on Mar. RNA that targets the Meloidogyn effector protein 6, 2014. Mc16D1OL. Patent Application Publication US 2015/025.9700 A1 OIGI9I?JÄI TOIGI9IDJÄI OIGI9I?IAI TOICI9IDJÄI OIC19I?IN TOICI9IDWI Patent Application Publication Sep. 17, 2015 Sheet 2 of 11 US 2015/025.9700 A1 e h; Figure 2A Figure 2B Figure 2C Figure 2D Figure 3 Patent Application Publication Sep. 17, 2015 Sheet 3 of 11 US 2015/025.9700 A1 COL E2 D1 D2 D4 COL E2 D1 D2 D4 Figure 4A Figure 4B 25000 ;20000 15000 s 10000 2 5000 DES E29 D54 D56 D57 DES E29 D54 D56 D57 Figure 5A Figure 5B 60 1800 50 3. -

Provincial Solidarities: a History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour

provincial solidarities Working Canadians: Books from the cclh Series editors: Alvin Finkel and Greg Kealey The Canadian Committee on Labour History is Canada’s organization of historians and other scholars interested in the study of the lives and struggles of working people throughout Canada’s past. Since 1976, the cclh has published Labour / Le Travail, Canada’s pre-eminent scholarly journal of labour studies. It also publishes books, now in conjunction with AU Press, that focus on the history of Canada’s working people and their organizations. The emphasis in this series is on materials that are accessible to labour audiences as well as university audiences rather than simply on scholarly studies in the labour area. This includes documentary collections, oral histories, autobiographies, biographies, and provincial and local labour movement histories with a popular bent. series titles Champagne and Meatballs: Adventures of a Canadian Communist Bert Whyte, edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant Working People in Alberta: A History Alvin Finkel, with contributions by Jason Foster, Winston Gereluk, Jennifer Kelly and Dan Cui, James Muir, Joan Schiebelbein, Jim Selby, and Eric Strikwerda Union Power: Solidarity and Struggle in Niagara Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage The Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada, 1929–39 Eric Strikwerda Provincial Solidarities: A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour / Solidarités provinciales: Histoire de la Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Nouveau-Brunswick David Frank A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour david fra nk canadian committee on labour history Copyright © 2013 David Frank Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, ab t5j 3s8 isbn 978-1-927356-23-4 (print) 978-1-927356-24-1 (pdf) 978-1-927356-25-8 (epub) A volume in Working Canadians: Books from the cclh issn 1925-1831 (print) 1925-184x (digital) Cover and interior design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. -

Mark Scott Managing Partner

MANAGEMENT TEAM MARK SCOTT MANAGING PARTNER Mr. Scott has over 35 years in real estate finance, including 17 years of international real estate and corporate investment banking experience with the Bank of Nova Scotia’s investment banking division, Scotia Capital. During his career at Scotia Capital, he was Associate, Vice President, Director and Managing Director in Toronto, culminating in overall leadership of the Hong Kong and Vancouver offices, with responsibility for investment banking and corporate banking client management and coverage of a wide range of industries. Mr. Scott has executed over US$10 billion of merger and acquisition, initial public offering, advisory, asset and company sales, and public and private debt financing transactions, including those for the following representative real estate clients: Reichmann International, Olympia & York, Canadian EMAIL Broadcasting Corporation, Cadillac Fairview, Canada Post Corporation, mark@balfourpacific.com Intrawest Development Corporation, and the BC Investment Management Corporation. He was lead advisor for the sale of the landmark 68-storey Scotia PHONE Plaza and the 40 Bay Street development site, both in Toronto. Corporate 604.806.3359 clients of Mr. Scott have included Westcoast Energy, Terasen Gas, Finning International Inc., Duke Energy, The Jim Pattison Group, Telus Corporation, Tricor Pacific Capital, and MDA Corporation. In Asia, Mr. Scott advised companies on cross-border mergers and acquisitions and private placements. He was advisor to the owners of the Fort Bonifacio Global City project in Manila, Philippines, while he was a director of Asian Capital Partners, a boutique mergers and acquisitions firm based in Hong Kong. Early in his career, Mr. Scott worked in property management with NuWest Developments and was asset manager for Morguard’s national property portfolio of 220 buildings. -

1 Canfor Corporation Annual Information Form Information in This

Canfor Corporation Annual Information Form Information in this Annual Information Form is as at February 4, 2015 unless otherwise indicated. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS FORWARD LOOKING INFORMATION ............................................................................................................... 2 CURRENCY ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 INCORPORATION ............................................................................................................................................. 2 CORPORATE STRUCTURE ................................................................................................................................. 2 BUSINESS OF CANFOR ..................................................................................................................................... 3 WOOD SUPPLY ................................................................................................................................................. 8 LUMBER .......................................................................................................................................................... 13 PULP AND PAPER ........................................................................................................................................... 14 OTHER OPERATIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Tomball German Festival Food Vendor List June 4-6, 2021

TOMBALL GERMAN FESTIVAL FOOD VENDOR LIST JUNE 4-6, 2021 VENDOR BOOTH B & D Farms M333 Bennett Concessions O108-110 Bennett Concessions O112-114-116 Berlin Food Factory M251-253-255 Beste verdammte Bratwürste (Best Damn Bratwursts) M217-219 BZ Honey M122 C&L Nut Co M241 Candy and Caramel Apples M133 Concession Services M140-142-144 Concession Services M157-159 Crepe Crazy M113 Daniela's Concession M206-208 Dippin Dots Ice Cream M135-137 Divine Dogs USA M332 Dracula's Chimney Cakes M234-236 Four Reasons M235-237 Fredericksburg Mini Donut Co. M302 Great Harvest Bread Co. M335 Helga’s Strudel M205-207 J.W. Korn M129-131 JJ's Concessions P9-10-11 Life Gave Us Lemons M323 Oh My Pizza Pie M103-105 Once Upon a Cone M325 Pham's Concession M355-357 Polonez Inc, dba Polonia Restaurant M348-350-352-354 PretzTex Stuffed Pretzels M324 Schnitzels & Giggles C112-114-116 Senor Burrito M407 Shuckers Roasted Corn M109-111 Snowbuddies Shaved Ice M154 Styria bakery M100-102 Ted Kamel Foods, LLC M301-303-305 The Baker's Man M146 The Fresh Lemonade Store M244 The Sauer Kraut Food Truck M132-134-136 Winkle Concessions C113-115-117 Zemer Rootbeer M210-212 TOMBALL GERMAN FESTIVAL MERCHANDISE VENDOR LIST JUNE 4-6, 2021 VENDOR BOOTH VENDOR BOOTH A Fresh Perspective Face and Body Art M304 Mom & Pops Mini Mall M227-229 Amber & Christmas Ornaments M152 Mr. Anderson M314 Art by Jonathan M421 Neu Life Chiropractic W122 Art of Twisted Nail LLC W124 Old Town Roasters M308 Ashwear International M317-319 Olive and Oak Designs M155 B&P ENTERPRISE M247 Pain Train Salsa M204 -

Sport Terminology

SPORT TERMINOLOGY Baton, bell lap, decathlon, discus, false start, field, foul, hammer, heptathlon, high jump, hurdles, javelin, lane, lap, long jump, marathon, middle-distance, pole-vault, relay, record, shot put, sprint, starting blocks, steeplechase, track, track and field, Athletics triple jump, Cross Country, etc. Alley, Back Alley, Backcourt, Balk, Baseline, Carry, Center or Base Position, Center Line, Clear, Court, Drive, Drop, Fault, Feint, Flick, Forecourt, Hairpin Net Shot, Halfcourt Shot, Kill, Let, Long Service Line, Match, Midcourt, Net Shot, Push Shot, Racquet, Rally, Serve, Service Court, Short Service Line, Shuttlecock, Smash, Badminton Wood Shot etc. Baseball Pinching, Home run, Base runner, Throw, Perfect game, Strike, Put out, etc. Cue, cannon, baulk, pot scratch, long jenny, short jenny, frame, spider, short and Billiards long rest, in-off, etc. Accidental Butt, Bleeder, Bolo Punch, Bout, Brawler, Break, Buckle, Canvas, Card, Caught Cold, Clinch, Corkscrew Punch, Cornerman, Counterpunch, Cross, Cutman, Dive, Eight Count, Glass Jaw, Haymaker, Kidney Punch Liver Shot, Low Blow, Mauler, Neutral Corner, Plodder, Ring Generalship, Roughhousing, Southpaw, Spar, Boxing Stablemate, Technical Knockout, Walkout Bout, Whiskers etc. Contract bridge, duplicate bridge, tricks, suite , rubber, trump, grand slam, little Bridge slam, etc. Billiards & Snooker Pull, Cue, Hit, Object ball, Break shot, Scoring, Cushion billiards, etc. , etc. Knock. out, Round, Ring Stoppage, Punch, Upper-cut, Kidney punch, Timing, Foot Boxing work, etc. Chess Gambit, stalemate, move, resign, checkmate, etc. Hat-trick, maiden, follow-on, declare, bowled, caught, run-out, leg before wicket(LBW), stumped, striker, slips, gully, short leg, silly, mid-on, point, cover, Cricket mid-off, bouncer, beamer, googly, full toss, drive, cut, pull, hook, flick, etc. -

Apb Coaches Manual

APB COACHES MANUAL Supplement to AIBA COACHES MANUAL published in August 2011 FOREWORD AIBA Professional Boxing Coaches Manual is designed as an addition to AIBA Coaches Manual helping the coach understand the fundamentals of AIBA Professional Boxing. The AIBA Professional Boxing Coaches Manual assists coaches’ development and enhances the qualities in coaching providing the coach with the knowledge and personal skills to manage a successful career in AIBA Professional Boxing. AIBA Coaches Commission 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................ 2 Part 1. About coaching in APB ........................................................................................... 5 1.1. Definition of Boxer in APB ....................................................................................... 5 1.2. Difference between AOB and APB , coaching aspects ........................................... 6 1.3. What is fundamental in APB ................................................................................... 7 Part 2. Coach in APB ......................................................................................................... 8 2.1. The role of the coach in APB ...................................................................................... 8 2.2. Responsibility before, during and after the competition ............................................... 8 2.2.1. Role of the coach in APB .................................................................................... -

List of Approved Food Items for Light Refreshment Restaurants

LIST OF APPROVED FOOD ITEMS FOR LIGHT REFRESHMENT RESTAURANTS Licensed light refreshment restaurants may only prepare and sell one of the following groups of food items for consumption on the premises – Group A (1) Noodles / vermicelli in soup with meat, offal, fish or sea food; (2) Wantun and dumplings in soup (also known as shui kau); (3) Boiled vegetables; (4) Tea, coffee, cocoa, any non-alcoholic drink or beverage made by adding water to prepared liquid or powder, and (5) Five self-specified snack items 【pre-prepared and supplied from approved / licensed sources, ready to eat after warming / reheating by electricity (excluding deep-frying and stir-frying )】*. or Group B (1) Rice congee with meat, offal, poultry, fish, sea food or frog; (2) Tea, coffee, cocoa, any non-alcoholic drink or beverage made by adding water to prepared liquid or powder; and (3) Five self-specified snack items 【pre-prepared and supplied from approved /licensed sources, ready to eat after warming / reheating by electricity (excluding deep-frying and stir-frying )】*. or Group C (any combination of the following seventeen items) (1) Bread, cakes and biscuits; (2) Toast including French toast; (3) Sandwiches; (4) Hot cakes, pancakes and waffles; (5) Oatmeal porridge and instant cereals; (6) Pastries (baking is not allowed but an electric warmer may be used to keep the pastries warm); (7) Eggs (boiled, poached, fried or scrambled); (8) Ham, bacon, western sausages, tinned meat and tinned fish; (9) Soup (prepared from tinned soup or powdered soup); (10) Macaroni -

Potato - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Potato - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Log in / create account Article Talk Read View source View history Our updated Terms of Use will become effective on May 25, 2012. Find out more. Main page Potato Contents From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Featured content Current events "Irish potato" redirects here. For the confectionery, see Irish potato candy. Random article For other uses, see Potato (disambiguation). Donate to Wikipedia The potato is a starchy, tuberous crop from the perennial Solanum tuberosum Interaction of the Solanaceae family (also known as the nightshades). The word potato may Potato Help refer to the plant itself as well as the edible tuber. In the region of the Andes, About Wikipedia there are some other closely related cultivated potato species. Potatoes were Community portal first introduced outside the Andes region four centuries ago, and have become Recent changes an integral part of much of the world's cuisine. It is the world's fourth-largest Contact Wikipedia food crop, following rice, wheat and maize.[1] Long-term storage of potatoes Toolbox requires specialised care in cold warehouses.[2] Print/export Wild potato species occur throughout the Americas, from the United States to [3] Uruguay. The potato was originally believed to have been domesticated Potato cultivars appear in a huge variety of [4] Languages independently in multiple locations, but later genetic testing of the wide variety colors, shapes, and sizes Afrikaans of cultivars and wild species proved a single origin for potatoes in the area -

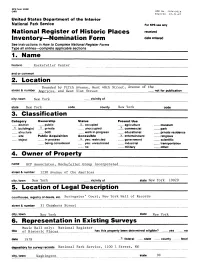

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections____________ 1. Name historic Rockefeller Center and or common 2. Location Bounded by Fifth Avenue, West 48th Street, Avenue of the street & number Americas, and West 51st Street____________________ __ not for publication city, town New York ___ vicinity of state New York code county New York code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private unoccupied x commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible _ x entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name RCP Associates, Rockefeller Group Incorporated street & number 1230 Avenue of the Americas city, town New York __ vicinity of state New York 10020 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Surrogates' Court, New York Hall of Records street & number 31 Chambers Street city, town New York state New York 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Music Hall only: National Register title of Historic Places has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1978 federal state county local depository for survey records National Park Service, 1100 L Street, NW ^^ city, town Washington_________________ __________ _ _ state____DC 7. Description Condition Check one Check one x excellent deteriorated unaltered x original s ite good ruins x altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Rockefeller Center complex was the final result of an ill-fated plan to build a new Metropolitan Opera House in mid-town Manhattan. -

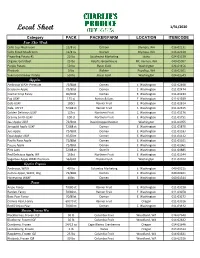

Local Sheet 1/31/2020

Local Sheet 1/31/2020 Category PACK PACKER/FARM LOCATION ITEMCODE New This Week Cello Cup Mushroom 12/8 oz Ostrom Olympia, WA 016-02131 Cello Sliced Mushroom 12/8 oz Ostrom Olympia, WA 016-02130 Fingerling Potato #1 20 lbs Southwind Marketing Idaho 024-01539 Organic Gold Beet 25 lbs Ralph's Greenhouse Mt. Vernon, WA 040-05097 Purple Potato 50 lbs Basin Gold Washington 024-01456 Rhubarb 5 lbs Richter Puyallup, WA 016-02301 Yukon Gold Baker Potato 50 lbs Basin Gold Washington 024-01549 Apples Ambrosia WAXF Premium 72/88ct Domex E. Washington 011-02468 Braeburn Apple 72/80ct Domex E. Washington 011-02474 Cosmic Crisp Fancy 40/60ct Domex E. Washington 011-01234 Fuji USXF 125 ct Borton & Sons E. Washington 011-01939 Gala USXF 100ct Rainier Fruit E. Washington 011-02614 Gala, USFCY 72/88 ct Rainier Fruit E. Washington 011-02615 Golden Delicious USXF 125ct Northern Fruit E. Washington 011-01176 Granny Smith USXF 100 ct Northern Fruit E. Washington 011-01751 Jazz Apple USXF 72/80ct David Doppenheimer Washington 011-01955 Jonagold Apple USXF 72/88 ct Domex E. Washington 011-01870 Juci Apple 72/88ct Domex E. Washington 011-01183 Opal Apple USXF 45/60ct Domex E. Washington 011-01112 Pacific Rose Apple 72/88ct Domex E. Washington 011-01101 Pazzaz Apple 72/88ct Domex E. Washington 011-01061 Pink Lady 72/88 ct Stemilt E. Washington 011-01885 Red Delicious Apple, WF 163ct Northern Fruit E. Washington 011-01544 Sugarbee Apple WAXF Premium 56/64ct Chelan Fresh Washington 011-02012 Apples Organic Ambrosia, WAXF 40 lbs Columbia Marketing E.