The Violin Maker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stowell Make-Up

The Cambridge Companion to the CELLO Robin Stowell Professor of Music, Cardiff University The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP,United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1999 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1999 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Adobe Minion 10.75/14 pt, in QuarkXpress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0 521 621011 hardback ISBN 0 521 629284 paperback Contents List of illustrations [page viii] Notes on the contributors [x] Preface [xiii] Acknowledgements [xv] List of abbreviations, fingering and notation [xvi] 21 The cello: origins and evolution John Dilworth [1] 22 The bow: its history and development John Dilworth [28] 23 Cello acoustics Bernard Richardson [37] 24 Masters of the Baroque and Classical eras Margaret Campbell [52] 25 Nineteenth-century virtuosi Margaret Campbell [61] 26 Masters of the twentieth century Margaret Campbell [73] 27 The concerto Robin Stowell and David Wyn Jones [92] 28 The sonata Robin Stowell [116] 29 Other solo repertory Robin Stowell [137] 10 Ensemble music: in the chamber and the orchestra Peter Allsop [160] 11 Technique, style and performing practice to c. -

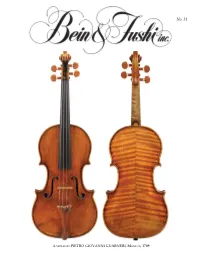

B&F Magazine Issue 31

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

A Violin by Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri

141 A VIOLIN BY GIUSEPPE GIOVANNI BATTISTA GUARNERI Roger Hargrave, who has also researched and drawn the enclosed poster, discusses an outstanding example of the work of a member of the Guarneri family known as `Joseph Guarneri filius Andrea'. Andrea Guarneri was the first He may never have many details of instruments by of the Guarneri family of violin reached the heights of his Joseph filius at this period recall makers and an apprentice of contemporary, the Amati school, this type of Nicola Amati (he was actually varnish, in combination with registered as living in the house Antonio Stradivarius, but he the freer hand of Joseph, gives of Nicola Amati in 1641). Andrea's does rank as one of the the instruments a visual impact youngest son, whose work is il - greatest makers of all time. never achieved by an Amati or , lustrated here, was called. We should not forget he with the exception of Stradi - Giuseppe. Because several of the sired and trained the great vari, by any other classical Guarneri family bear the same del Gesu' maker before this time. christian names, individuals have traditionally been identified by a It should be said, however, suffix attached to their names. that the varnish of Joseph filius Thus, Giuseppe's brother is known as `Peter Guarneri varies considerably. It is not always of such out - of Mantua' to distinguish him from Giuseppe's son, standing quality the same can be said of Joseph's pro - who is known as `Peter Guarneri of Venice'. duction in general. If I were asked to describe the instruments of a few of the great Cremonese makers Giuseppe himself is called 'Giuseppe Guarneri filius in a single word, I would say that Amatis (all of them) Andrea' or, more simply, `Joseph filius' to distinguish are `refined', Stradivaris are `stately', del Gesus are him from his other son, the illustrious 'Giuseppe `rebellious' and the instruments of Joseph filius An - Guarneri del Gesu'. -

“Triennale” Violin Making Competition Antonio Stradivari Cremona September 4Th - October 11Th 2015 Exhibition from September 24Th

14th International “Triennale” Violin Making Competition Antonio Stradivari Cremona September 4th - October 11th 2015 Exhibition from September 24th www.museodelviolino.org Graphic designer: Corrado Testa Graphic designer: Corrado regulation Dear Maestros, 1 the 14th International Triennale Violin Making Competition to be held in September 2015 will be of special importance. On the one hand, it will coincide with the Universal Exposition Milano EXPO 2015 in which Cremona aims at playing a leading role and being a pole of attraction for a great number of visitors. Cremonese violin making will in fact be signifi cantly represented in the Italian Pavilion; the winners of the Competition will be presented at the Pavilion the day before the offi cial awards ceremony that will be held, as is tradition, in the beautiful Teatro Ponchielli. On the other hand, it will be the fi rst Competition to be disputed after the opening of the Museo del Violino, a museum where the history of fi ve hundred years of Cremonese violin making is illustrated in a direct and fascinating way. The last room of the exhibition 2 is especially dedicated to contemporary violin making and the history of the Triennale Competition of Cremona. All the gold medal winning instruments are displayed here, in the same place as the great masterpieces of the past made by Stradivari, Amati and Guarneri, just to mention the main ones. We believe this to be a great honour for those makers who were awarded fi rst prize in this Competition and, at the same time, a great incentive to participate with enthusiasm in a contest which is universally known as “the Olimpics of Violin Making” for its reputation, number of entrants and the quality of selected instruments. -

Stradivarifestival

STRADIVARIfestival Cremona incanta. E suona Musical Enchantment in Cremona Cremona, Italy 14.09 - 12.10.2014 CONSIGLIO DI AMMINISTRAZIONE Fondazione Museo del Violino Antonio Stradivari Cremona - Soci Fondatori Gianluca Galimberti, Paolo Salvelli Paolo Bodini, Luigi Vinci, Roberto Zanchi CONSIGLIO GENERALE Gianluca Galimberti, Presidente Giovanni Arvedi, Presidente onorario Paolo Salvelli, Vicepresidente Paolo Bodini, Presidente “friends of Stradivari” Gian Domenico Auricchio, Stefano Bolis Chiara Bondioni, Manuela Bonetti Rossano Bonetti, Giuseppe Ghisani Renzo Rebecchi, Alessandro Tantardini Luigi Vinci, Roberto Zanchi Direttore Generale Museo del Violino Virginia Villa Direttore Artistico Stradivari Festival Francesca Colombo Tutto ciò che valorizza le eccellenze della nostra città vede The administration supports everything that promotes our city’s merits. l’Amministrazione presente come sostegno e come promozione. The council is working on extensive and detailed programming, based “ Come Giunta stiamo lavorando ad una programmazione ampia “ on alliances and shared projects. We’d like to thank the Museo del e precisa, fatta di alleanze e progetti condivisi. L’iniziativa Violino and Cavalier Giovanni Arvedi for making the STRADIVARIfestival STRADIVARIfestival, voluta dal Museo del Violino e dal Cavalier a reality. It’s an opportunity for the whole city. Giovanni Arvedi, che ringraziamo, è un’opportunità per tutta la città. Gianluca Galimberti Gianluca Galimberti Mayor of Cremona - President of Fondazione Museo del Violino Antonio Stradivari Sindaco di Cremona - Presidente Fondazione Museo del Violino Antonio Stradivari The STRADIVARIfestival is a privileged occasion, bringing together STRADIVARIfestival è un momento privilegiato dove, nel segno creativity and scientific rigour, product and gesture, symbolic content della liuteria, trovano sintesi creatività e rigore scientifico, prodotto “ and wonderfully physical objects, all under the banner of violin “ e gesto, contenuti simbolici e oggetti meravigliosamente fisici. -

The Working Methods of Guarneri Del Gesů and Their Influence Upon His

45 The Working Methods of Guarneri del Gesù and their Influence upon his Stylistic Development Text and Illustrations by Roger Graham Hargrave Please take time to read this warning! Although the greatest care has been taken while compiling this site it almost certainly contains many mistakes. As such its contents should be treated with extreme caution. Neither I nor my fellow contributors can accept responsibility for any losses resulting from information or opin - ions, new or old, which are reproduced here. Some of the ideas and information have already been superseded by subsequent research and de - velopment. (I have attempted to included a bibliography for further information on such pieces) In spite of this I believe that these articles are still of considerable use. For copyright or other practical reasons it has not been possible to reproduce all the illustrations. I have included the text for the series of posters that I created for the Strad magazine. While these posters are all still available, with one exception, they have been reproduced without the original accompanying text. The Labels mentions an early form of Del Gesù label, 98 later re - jected by the Hills as spurious. 99 The strongest evi - Before closing the body of the instrument, Del dence for its existence is found in the earlier Gesù fixed his label on the inside of the back, beneath notebooks of Count Cozio Di Salabue, who mentions the bass soundhole and roughly parallel to the centre four violins by the younger Giuseppe, all labelled and line. The labels which remain in their original posi - dated, from the period 1727 to 1730. -

A Brief History of the Violin

A Brief History of the Violin The violin is a descendant from the Viol family of instruments. This includes any stringed instrument that is fretted and/or bowed. It predecessors include the medieval fiddle, rebec, and lira da braccio. We can assume by paintings from that era, that the three string violin was in existence by at least 1520. By 1550, the top E string had been added and the Viola and Cello had emerged as part of the family of bowed string instruments still in use today. It is thought by many that the violin probably went through its greatest transformation in Italy from 1520 through 1650. Famous violin makers such as the Amati family were pivotal in establishing the basic proportions of the violin, viola, and cello. This family’s contributions to the art of violin making were evident not only in the improvement of the instrument itself, but also in the apprenticeships of subsequent gifted makers including Andrea Guarneri, Francesco Rugeri, and Antonio Stradivari. Stradivari, recognized as the greatest violin maker in history, went on to finalize and refine the violin’s form and symmetry. Makers including Stradivari, however, continued to experiment through the 19th century with archings, overall length, the angle of the neck, and bridge height. As violin repertoire became more demanding, the instrument evolved to meet the requirements of the soloist and larger concert hall. The changing styles in music played off of the advancement of the instrument and visa versa. In the 19th century, the modern violin became established. The modern bow had been invented by Francois Tourte (1747-1835). -

Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri Del Gesù: a Paper-Chase and a Proposition

Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù: a paper-chase and a proposition Nicholas Sackman © 2021 During the past 200 years various investigators have laboured to unravel the strands of confusion which have surrounded the identity and life-story of the violin maker known as Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù. Early-nineteenth-century commentators – Count Cozio di Salabue, for example – struggled to make sense of the situation through the physical evidence of the instruments they owned, the instruments’ internal labels, and the ‘understanding’ of contemporary restorers, dealers, and players; regrettably, misinformation was often passed from one writer to another, sometimes acquiring elaborations on the way. When research began into Cremonese archives the identity of individuals (together with their dates of birth and death) were sometimes announced as having been securely determined only for subsequent investigations to show that this certainty was illusory, the situation being further complicated by the Italian habit of christening a new- born son with multiple given names (frequently repeating those already given to close relatives) and then one or more of the given names apparently being unused during that new-born’s lifetime. During the early twentieth century misunderstandings were still frequent, and even today uncertainties still remain, with aspects of del Gesù’s chronology rendered opaque through contradictory or no documentation. The following account examines the documentary and physical evidence. ***** NB: During the first decades of the nineteenth century there existed violins with internal labels showing dates from the 1720s and the inscription Joseph Guarnerius Andrea Nepos. The Latin Dictionary compiled by Charlton T Lewis and Charles Short provides copious citations drawn from Classical Latin (as written and spoken during the period when the Roman Empire was at its peak, i.e. -

Special Winter, 2011 Sale List

Special Winter, 2011 sale list 50% off any book 60% off purchase of 2-10 books 70% off purchase of 11 or more books 1. Abele, H. and Niederheitmann, F. THE VIOLIN: Its History & Construction Illustrated & Described, From Many Sources. Together with a List of Italian and Tyrolese Violin Makers. Translated by John Broadhouse. London: William Reeves, n. d. vi, 151 pp., frontispiece, 28 illustrations, music plate. (5 x 7 1/2 inches, covers sl. worn) $30.00 Sold! 2. Adler, Hans. TRAVEL THE RAINBOW. The Story of the First Violin. Vantage Press, 1962. 240 pp. (5 1/2 x 8 1/4 inches, sl. wear to covers) A novel about Gasparo da Salo. $35.00 Sold! 3. Alton, Robert. VIOLIN MAKING AND REPAIRING. London: Cassell and Co., Ltd., 1923. 152 pp., 61 illustrations. (4 3/4 x 7 1/4 inches, paper covers, spine worn, covers a bit worn) Includes full and detailed instructions for making a violin or bow, including selecting wood, making the bass bar, etc. $35.00 4. Arakelian, Sourene. THE VIOLIN. Precepts and Observations of a Luthier. My Varnish, Based on Myrrh. Frankfurt, 1981. 81 pp., frontispiece. (5 1/4 x 8 1/4, stiff paper covers) $35.00 5. Balfoort, Dirk J. ANTONIUS STRADIVARIUS. Amsterdam, n.d. 60 pp., numerous illustrations. (boards sl. warped) A biography of Stradivari in Dutch, with a survey of his works.$30.00 Sold! 6. Barjansky, Serge. THE PHYSICAL BASIS OF TONE PRODUCTION for String Instrument Players. 1939. 19 pp. (6 x 9 1/4 inches, paper covers, minor wear, belonged to Ernest Doring) $35.00 7. -

Violin, I the Instrument, Its Technique and Its Repertory in Oxford Music Online

14.3.2011 Violin, §I: The instrument, its techniq… Oxford Music Online Grove Music Online Violin, §I: The instrument, its technique and its repertory article url: http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com:80/subscriber/article/grove/music/41161pg1 Violin, §I: The instrument, its technique and its repertory I. The instrument, its technique and its repertory 1. Introduction. The violin is one of the most perfect instruments acoustically and has extraordinary musical versatility. In beauty and emotional appeal its tone rivals that of its model, the human voice, but at the same time the violin is capable of particular agility and brilliant figuration, making possible in one instrument the expression of moods and effects that may range, depending on the will and skill of the player, from the lyric and tender to the brilliant and dramatic. Its capacity for sustained tone is remarkable, and scarcely another instrument can produce so many nuances of expression and intensity. The violin can play all the chromatic semitones or even microtones over a four-octave range, and, to a limited extent, the playing of chords is within its powers. In short, the violin represents one of the greatest triumphs of instrument making. From its earliest development in Italy the violin was adopted in all kinds of music and by all strata of society, and has since been disseminated to many cultures across the globe (see §II below). Composers, inspired by its potential, have written extensively for it as a solo instrument, accompanied and unaccompanied, and also in connection with the genres of orchestral and chamber music. Possibly no other instrument can boast a larger and musically more distinguished repertory, if one takes into account all forms of solo and ensemble music in which the violin has been assigned a part. -

Appendix: Francesco Stradivari and His Salabue Violin

Appendix Francesco Stradivari and his Salabue violin Given the willingness of late-eighteenth-century collectors and dealers to falsify labels and modify instruments, and given the lack of respect for the creative artistry of craftsmen of the calibre of Stradivari, Guarneri, Bergonzi, and Guadagnini – artistry which should have been held sacrosanct – it is sometimes only with difficulty that certainties of manufacture and authorship can be established to everyone’s satisfaction. Even with a violin maker who apparently made very few instruments the uncertainties often outweigh the certainties by a wide margin, and such a situation exists with some of the instruments made by, or attributed to, Antonio Stradivari’s eldest son, Giacomo Francesco. Two of Francesco’s early violins, label-dated 1707 and 1716, are illustrated by Simone Sacconi,1 and were listed on the Cozio.com website with the identification numbers 4993 and 4992. The website also identified a 1713 violin (no. 6345) with the label Franciscus Stradivarius cremonensis filius Antonii faciebat Anno 1713, a cello (no. 4453) labelled Sotto la disciplina2 di Antonio Stradiuario F. in Cremona 1733, the Le Besque violin (attributed to the year 1742 by Cozio.com but ‘has a Stradivari [Antonio?] label of 1734’), and the Petersen violin which the website attributed to circa 1740 despite the label: Antonius Stradivarius Cremonensis Faciebat Anno 1734. The Tarisio.com website (in August 2014) illustrated just five violins by Francesco: the Oliveira (1730), un-named (1732), Humser (1740), Salabue (1742), and the Le Besque (1742).3 ***** A violin which is associated with Francesco Stradivari – a violin which is label-dated 17304 – is twice described by Count Cozio (1A and 1B, below), with a third description (2, see later) including detailed measurements of what, at first sight, appears to be the same violin. -

OCTOBER 2010 AUCTION Fine Instruments & Bows

OCTOBER 2010 AUCTION Fine instruments & bows www.tarisio.com OCTOBER 13 & 14, 2010 • 2010 & 14, 13 OCTOBER The Molitor Stradivarius of 1697 The Molitor first surfaces in Paris around the turn both of which have since been lost. Upon of the 19th Century in the hands of Madame receipt by Curtis, the violin was branded Juliette Récamier (1777–1849), a prominent “CURTIS PHILA” to the uncut lower rib and socialite and patroness of the arts in post- entered Curtis’s formidable fleet of loaned revolutionary France. Married at the age of instruments. During its time at Curtis The fifteen to a wealthy banker 30 years her senior, Molitor was loaned to several promising Madame Récamier held a fashionable salon that students including Henri Temianka, was frequented by leading artists, musicians and Jascha Brodsky, Ethel Stark and others. Elmar Oliveira the political elite of French Empire society. In In 1936 The Molitor was sold to the firm of New York addition to The Molitor, Madame Récamier owned W. E. Hill & Sons. Madame Recamier, painted by another Stradivarius from the year 1727. It’s not Jacques-Louis David, 1800 In 1937 the Hills sold the violin to a Mr. R. A. Bower of Somerset, England known for certain how Madame Récamier came and in 1957 E. R. Voigt sold the violin to a Miss Muriel Anderson of into possession of these two violins, but Herbert Londonderry in Northern Ireland. Goodkind’s Violin Iconography of Antonio Stradivarius and other references name their first owner as none other than Napoleon Bonaparte. Elmar Oliveira acquired The Molitor at Christie’s in 1989 and concertized and recorded with it until he acquired the c.