Crossing Charges Changes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Potential Options Table

POTENTIAL OPTIONS CODE WORKING GROUPS TOS TRAFFIC OPERATIONS AND SAFETY GM GOODS MOVEMENT TS TRANSIT SERVICES BP BIKE/PEDESTRIAN ENV ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES/ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT # CODE NO. DESCRIPTION (**) 1 TOS-1 Encourage employers to offer flexible schedules so traffic is not always congested at the same times. 2 TOS-2 Improve signage along Cross Bronx Expressway. 3 TOS-3 Establish breakdown lane and shoulders on major roadways. 4 TOS-4 Examine local and mainline bridges to facilitate traffic flow. 5 TOS-5 Eliminate TDM measures to divert traffic to alternate routes-this hurts local communities. 6 TOS-6 Create an exit on Cross Bronx Expressway near the Sheridan Expressway (near Boston Road) in the area of the former industrial park (174 – 176th Streets) which will become a 136,00 square ft. retail center. 7 TOS-7 Improve road conditions in the Bronx. 8 TOS-8 The intersection of Devoe Avenue and 177th Street should be examined so that its congestion problem can be improved. 9 TOS-9 Improve operational/geometric conditions along parallel major arterials in Major Deegan Expressway corridor (e.g., University Avenue and Grand Concourse). 10 TOS-10 Construct service roads/c-d roads on Major Deegan Expressway. Options are continuous, partial and directional (nb/sb) service/c-d roads. 11 TOS-11 Improve mainline horizontal geometry on Major Deegan Expressway, south of 145th Street. 12 TOS-12 Examine option to divert Cross Bronx Expressway-Henry Hudson Parkway traffic to Washington Bridge as alternative route to the Alexander Hamilton Bridge. Option to increase outer lane usage and to reduce congestion on inner lanes on Trans- Manhattan Expressway. -

PRIMARY CONTEST LIST Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021

PRIMARY CONTEST LIST Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021 Printed On: 6/17/2021 4:24:00PM BOARD OF ELECTIONS PRIMARY CONTEST LIST TENTATIVE IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUBJECT TO CHANGE PRINTED AS OF: Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021 6/17/2021 4:24:00PM New York - Democratic Party Name Address Democratic Party Nominations for the following offices and positions: Mayor Public Advocate City Comptroller Borough President District Attorney Member of the City Council Judge of the Civil Court - District Female District Leader Female District Leader Male District Leader Delegate to Judicial Convention Alternate Delegate to the Judicial Convention Page 2 of 17 BOARD OF ELECTIONS PRIMARY CONTEST LIST TENTATIVE IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUBJECT TO CHANGE PRINTED AS OF: Primary Election 2021 - 06/22/2021 6/17/2021 4:24:00PM New York - Democratic Party Name Address Mayor - Citywide Aaron S. Foldenauer 90 Washington Street New York, NY 10006 Dianne Morales 200 Jefferson Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11216 Scott M. Stringer 25 Broad Street 12S New York, NY 10004 Raymond J. McGuire 145 Central Park West New York, NY 10023 Maya D. Wiley 1519 Albemarle Road Brooklyn, NY 11226 Paperboy Love Prince 852 Monroe Street 3 Brooklyn, NY 11221 Art Chang 384 Sterling Place Brooklyn, NY 11238 Kathryn A. Garcia 591 Carroll Street Brooklyn, NY 11215 Eric L. Adams 936 Lafayette Avenue FL 1 Brooklyn, NY 11221 Isaac Wright Jr. 785 Seneca Avenue Ridgewood, NY 11385 Shaun Donovan 139 Bond Street Brooklyn, NY 11217 Andrew Yang 650 West 42 Street New York, NY 10036 Joycelyn Taylor 153 Jefferson Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11216 Public Advocate - Citywide Anthony L. -

Bridges, Tunnels and Rail Advisory

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 25, 2020 Contact: The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey 212-435-7777 BRIDGES, TUNNELS AND RAIL ADVISORY Lane closings planned at the George Washington Bridge, Holland Tunnel and Outerbridge Crossing Face coverings required for anyone using Port Authority facilities to prevent spread of COVID-19 Lanes will be closed this week at the George Washington Bridge, Holland Tunnel and Outerbridge Crossing. As a reminder to the traveling public, face coverings are required for anyone using Port Authority facilities to help protect fellow passengers and employees from the spread of COVID- 19, including PATH trains and stations; the World Trade Center transportation hub; the Midtown Bus Terminal and George Washington Bridge Bus Station; the Port Authority’s airports and on AirTrain. Additionally, terminal access at John F. Kennedy, Newark Liberty and LaGuardia airports remains restricted to ticketed passengers, airport employees, and those who otherwise demonstrate a need to enter the facility for airport business. Travelers entering the region are also reminded that a tri-state travel advisory currently requires anyone entering New York, New Jersey and Connecticut from states with significant community spread of COVID-19 to quarantine for 14 days. Essential workers and travelers with layovers in the tri-state area are exempt. More information is available here for New York and New Jersey. George Washington Bridge: • From 10 p.m. Friday, Sept. 25, to 8 a.m. Saturday, Sept. 26, two westbound lanes on the upper level and the two westbound lanes of the upper level Trans-Manhattan Expressway will be closed. -

New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) Decreased to 793

Appendix A BRIDGE CAPITAL PROGRAM East River Bridge Rehabilitation Plans A-1 Bridges Under Construction A-2 Component Rehabilitation A-3 Bridges Under Design A-4 216 2017 BRIDGES AND TUNNELS ANNUAL CONDITION REPORT APPENDIX A-1 MANHATTAN BRIDGE REHABILITATION ITEMS TOTAL ESTIMATED COST Est. Cost ($ in millions) Repair floor beams. (1982) 0.70* Replace inspection platforms, subway stringers on approach spans. (1985) 6.30* Install truss supports on suspended spans. (1985) 0.50* Partial rehabilitation of walkway. (1989) 3.00* Rehabilitate truss hangers on east side of bridge. (1989) 0.70* Install anti-torsional fix (side spans) and rehabilitate upper roadway decks on approach spans on east side; replace drainage system on approach spans, install new lighting on entire upper roadways east side, including purchase of fabricated material for west side of bridge. (1989) 40.30* Eyebar rehabilitation - Manhattan anchorage Chamber “C.” (1988) 12.20* Replacement of maintenance platform in the suspended span. (1982) 4.27* Reconstruct maintenance inspection platforms, including new rail and hanger systems and new electrical and mechanical systems; over 2,000 interim repairs to structural steel support system of lower roadway for future functioning of roadway as a detour during later construction contracts. (1992) 23.50* Install anti-torsional fix on west side (main and side spans); west upper roadway decks, replace drainage systems on west suspended and approach spans; walkway rehabilitation (install fencing, new lighting on west upper roadways -

STATE of NEW YORK RELEASE: IMMEDIATE 2/15/2019 DEPARTMENT of TRANSPORTATION CONTACT: Thomas G

STATE OF NEW YORK RELEASE: IMMEDIATE 2/15/2019 DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CONTACT: Thomas G. Bayer (718)482-4002 REGION 11 ***** T R A F F I C A D V I S O R Y ***** All lane closures listed are expected to be in place, WEATHER PERMITTING: Bronx Arthur Sheridan Expressway 2/16/2019 • One lane closed S/B from East 173rd Street to Westchester Avenue from 10:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. 2/18/2019 – 2/23/2019 • One lane closed S/B from East 173rd Street to Westchester Avenue from 10:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. Bronx River Parkway 2/18/2019 - 2/22/2019 (NEW THIS WEEK) • Right lane closed N/B between Morris Park Avenue and Allerton Avenue from 9:30 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. • Right lane closed S/B between Allerton Avenue and Morris Park Avenue from 10:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. 2/18/2019 - 2/22/2019 • One lane closed N/B between Mosholu Parkway /Allerton Avenue and Gun Hill Road from 9:30 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. • One lane closed S/B between Gun Hill Road and Mosholu Parkway /Allerton Avenue from 10:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. 2/18/2019 – 2/22/2019 • Right shoulder closed Both Directions from Story Avenue to East 233rd Street from 7:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. Note: Remove Existing Stubs and Finish digging locations where rocks hits at Various Locations. Bruckner Expressway Traffic Pattern: • The New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) is advising motorists of a change in traffic pattern on a section of the ramp from the westbound Bruckner Expressway (I-278) to the northbound Major Deegan Expressway (I-87) in the Bronx. -

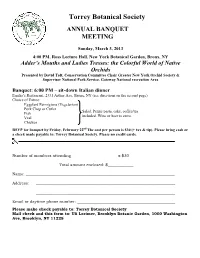

2013 Banquet RSVP

Torrey Botanical Society ANNUAL BANQUET MEETING Sunday, March 3, 2013 4:00 PM, Ross Lecture Hall, New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY Adder’s Mouths and Ladies Tresses: the Colorful World of Native Orchids Presented by David Taft, Conservation Committee Chair Greater New York Orchid Society & Supervisor National Park Service, Gateway National recreation Area Banquet: 6:00 PM – sit-down Italian dinner Emilia’s Restaurant, 2331 Arthur Ave, Bronx, NY (see directions on the second page) Choice of Entree: Eggplant Parmigiana (Vegetarian) Pork Chop or Cutlet Salad, Penne pasta, cake, coffee/tea Fish included. Wine or beer is extra. Veal Chicken RSVP for banquet by Friday, February 22nd The cost per person is $30 (+ tax & tip). Please bring cash or a check made payable to: Torrey Botanical Society. Please no credit cards. Number of members attending x $30 Total amount enclosed: $_____________ Name: ____________________________________________________________________________ Address: _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ Email or daytime phone number: __________________________________________________ Please make check payable to: Torrey Botanical Society Mail check and this form to: Uli Lorimer, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, 1000 Washington Ave, Brooklyn, NY 11225 Directions to Emilia’s Restaurant Map and Driving directions: Emilia’s Restaurant 2331 Arthur Ave FROM NYBG: Turn left out of NYBG and Bronx, NY 10458 follow Southern Blvd around the Garden, past (corner with Hughes Ave) Fordham University. Stay on Southern Blvd (left) as the road splits into Southern Blvd and th 718-367-5915 Crotona Ave. Continue to E. 187 St (the second light after you cross Fordham Rd). Turn right th onto E. 187 St, continue for 7 blocks to Arthur We will be carpooling from NYBG to Ave, then turn left. -

Contact Us At: 212-305-0114

New York-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley’s Children’s Hospital Pediatric Urology Department 3959 Broadway, 11th Floor New York, NY 10032 Between 165th Street and Broadway There are two entrances to the Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital. The main entrance is located on Broadway at 165th Street. The glass atrium entrance, allowing wheel chair and stroller accessibility, is located on 167th Street and Broadway. The Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital is located on Broadway between 165th and 167th Street in Washington Heights, near the New York side of the George Washington Bridge, and is easily accessible by car, bus and subway. From Upstate New York and New Jersey: After crossing the George Washington Bridge, follow signs to the Henry Hudson Parkway (also called the West Side Highway). Take the Riverside Drive exit and proceed South to 165th Street (the first left). Take 165th Street one block to Fort Washington Avenue. Take a left at Fort Washington Avenue to 168th Street. At 168th Street, make a right and proceed to Broadway. Take a right on Broadway. The Hospital will be on your right. From Riverdale and Westchester via the Saw Mill River Parkway: Exit the Henry Hudson Parkway at the Riverside Drive immediately pas the George Washington Bridge. See directions from Riverside Drive above. From Westchester, Connecticut, and the East Side of Manhattan via major Deegan, Cross Bronx Expressway or Harlem River Drive: Approaching the George Washington Bridge, take the Henry Hudson Parkway, stay on the left and follow signs to Riverside Drive. Follow directions above from Riverside Drive. From West Side of Manhattan: Take Henry Hudson Parkway to Exit 15-Riverside Drive South. -

New York (City) 2240137 JCT US 9 & HARLEM RIVER 9 9 04011032 METRO NO COMMUTER 42 - City 1961 11/22/2019 Y

NY State Highway Bridge Data: August 31, 2021 New York County Year Date BIN Built or of Last Poor Region County Municipality Location Feature Carried Feature Crossed Owner Replaced Inspectio Status n N New York New York (City) 2240137 JCT US 9 & HARLEM RIVER 9 9 04011032 METRO NO COMMUTER 42 - City 1961 11/22/2019 Y N New York New York (City) 2229349 4 MI NE ROUTE 9A+79 ST 9A 9A04011016 158TH STREET 42 - City 1939 11/16/2020 Y N New York New York (City) 2229410 6.4 MI NE ROUTE 9A+79 ST 9A 9A04011041 ACCESS RD TO HHPS 2U - MTA Bridges and Tunnels (aka 1937 TBTA) 08/02/2019 N N N New York New York (City) 5521258 SH 9A & SPUYTEN DUYVIL CK 9A 9A04011093 Henry Hudson Parkway 2U - MTA Bridges and Tunnels (aka 1937 TBTA) 09/21/2019 Southbound N New York New York (City) 5521257 JCT SH 9A & HARLEM RIVER 9A 9A04011093 METRO NO COMMUTER 2U - MTA Bridges and Tunnels (aka 1935 TBTA) 10/09/2019 N N New York New York (City) 2257569 WEST SIDE HIGHWAY-W 59 ST 9A 9AX4M11064 59TH STREET 42 - City 1931 08/21/2020 N N New York New York (City) 2229420 6.5 MI NE ROUTE 9A+79 ST 9AX DYCKMAN STREET 2U - MTA Bridges and Tunnels (aka 1937 TBTA) 08/02/2019 N N New York New York (City) 2240047 QUEENSBORO BR OVR EAST RV 25 25 04011004 EAST RIVER 42 - City 1909 10/28/2020 N N New York New York (City) 224004D QUEENSBORO BR OVR EAST RV 25 X EAST 59TH STREET 42 - City 1929 04/03/2020 N N New York New York (City) 224004C QUEENSBORO BR OVR EAST RV 25 X EAST 60TH STREET 42 - City 1952 04/22/2020 N N New York New York (City) 2240048 QUEENSBORO BR OVER EAST R 25 X EAST RIVER -

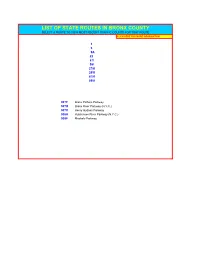

List of State Routes in Bronx County Select a Route to View Most Recent Traffic Counts for That Route Click Here for More Information

LIST OF STATE ROUTES IN BRONX COUNTY SELECT A ROUTE TO VIEW MOST RECENT TRAFFIC COUNTS FOR THAT ROUTE CLICK HERE FOR MORE INFORMATION 1 9 9A 22 87I 95I 278I 295I 678I 895I 907F Bronx Pelham Parkway 907H Bronx River Parkway (N.Y.C.) 907V Henry Hudson Parkway 908A Hutchinson River Parkway (N.Y.C.) 908F Mosholu Parkway NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 2003 Traffic Volume Report for Bronx COUNTY Touring Section Start Description End Description Count Route Length Year AADT 1 0.07 NEW YORK CO LINE ACC RT 87I MAJOR DEEGAN EXPR 00 177899 1 0.58 ACC RT 87I MAJOR DEEGAN EXPR ACC JEROME AVE 99 123604 1 0.63 ACC JEROME AVE END RT 95I OLAP WEBSTER AVE 03 157039 1 1.43 END RT 95I OLAP WEBSTER AVE FORDHAM RD 98 15174 1 0.99 FORDHAM RD RT 907H BRONX RIVER PKWY SOU 93 34394 1 0.31 RT 907H BRONX RIVER PKWY SOU PELHAM PKWY BOSTON POST RD R 97 46026 1 1.39 PELHAM PKWY BOSTON POST RD R GUN HILL RD 01 15500 1 1.64 GUN HILL RD RT 22 PROVOST AVE 02 25258 1 0.58 RT 22 PROVOST AVE WESTCHESTER CO LINE 03 21139 9 0.80 BRONX CO LN VAN CORTLAND SOUTH 02 11504 9 0.98 VAN CORTLAND SOUTH START 9A OLAP H.H. PKY 01 17434 9 0.80 START 9A OLAP H.H. PKY WESTCHESTER CO LN 03 16163 9A 0.33 BRONX CO LN KAPPOCK ST 03 69100 9A 1.97 KAPPOCK ST END 907V H.H. -

2015-16 Manhattan College

Manhattan College 1 Location The College is situated along Manhattan College Parkway on the heights above Van Cortlandt Park (242nd Street and Broadway) in the Riverdale section of New York City. It is a short distance from the 242nd Street station of the Broadway Seventh Avenue Subway, and can be easily reached from any part of the metropolitan or suburban areas. The exit of the Henry Hudson Parkway (West Side Highway) located at 239th Street several blocks to the west of the College puts the campus within easy reach of New Jersey. The College is also within easy commuting distance from Long Island and Westchester and Rockland counties because of its proximity to the New York State Thruway and the Major Deegan Expressway (exit at Van Cortlandt Park South or West 240th Street). Campus Map (http://manhattan.edu/admissions/tour) Directions to Manhattan College By Car: From Long Island Robert F. Kennedy Bridge (Triborough Bridge) (from South) Follow signs to Major Deegan Expressway North (I-87), exit at Van Cortlandt Park South, bear right off ramp and bear right onto Broadway. At second traffic light, turn left and then left again onto Manhattan College Parkway. Proceed up hill to main gate on right. Whitestone or Throgs Neck Bridge (from East) To Cross Bronx Expressway (I-95), to Major Deegan Expressway (I-87) North, exit at Van Cortlandt Park South, bear right off ramp and bear right onto Broadway. At second traffic light, turn left and then left again onto Manhattan College Parkway. Proceed up hill to main gate on right. -

Amtrak® ENGINEERING 01/25/01 REVISED DATE EP3014 PRACTICES 06/20/2008 TITLE

000380 PIN: 84116MNBR984 E-PIN: 84116B0032_______ Book/Receipt No.: 2 of 2 THE CITY OF NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION (“NYCDOT”) THE DIVISION OF BRIDGES POLLY TROTTENBERG COMMISSIONER PROPOSAL FOR BIDS, BID, DETAIL SPECIFICATIONS AND STANDARD CONSTRUCTION CONTRACT FOR Contract No. HBM1172 Rehabilitation of Henry Hudson Parkway Viaduct nd nd From W. 72 Street To W. 82 Street B.I.N. 2- 22928-9 Contract No. HBM1173 Rehabilitation of Henry Hudson Parkway Viaduct From W. 94th Street To W. 98th Street B.I.N. 2- 26725-0 Together With All Work Incidental Thereto BOROUGH OF MANHATTAN Bid Opening: 11:00 A.M. on November 22, 2016 Location: 55 Water Street, Ground Floor, Bid Room 000381 ATTACHMENT 3j S - PAGES SPECIAL PROVISIONS NOTICE THE PROVISIONS CONTAINED IN THIS SECTION (S-PAGES) ARE THE NYCDOT PROJECT SPECIFIC SPECIAL PROVISIONS. THESE PROVISIONS MODIFY AND SUPERSEDE PORTION OF T HE NYSDOT STANDARD SPECIFICATIONS AS WELL AS ALL NYSDOT REVISIONS THERETO. PIN: 84116MNBR984 S-1 Rehabilitation of Henry Hudson Parkway Viaduct EPIN: 84116B0032 000382 SPECIAL PROVISIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM NO. DESCRIPTION PAGE NO. 1 SCOPE AND DESCRIPTION S-5 2 WORK ZONE TRAFFIC CONTROL (WZTC) S-6 3 STANDARDS AND LIST OF ITEMS S-7 4 PROGRESS PHOTOGRAPHS S-8 5 PROGRESS VIDEO MOVIE S-9 6 CONTRACT DRAWINGS S-10 7 RECORD AS-BUILT, SHOP, WORKING DRAWINGS AND ELECTRONIC S-18 MEDIA 8 HOLIDAY EMBARGO S-19 9 SUPERINTENDENT S-19 10 EXISTING DIMENSIONS S-19 11 RESPONSIBILITY OF CONTRACTOR FOR PLANT AND METHODS S-19 12 NIGHT WORK S-20 13 RESTORATION OF DAMAGED AREAS -

September 2021 Page 1 Seg Sponsor Boro Highway Dir Location From

Citywide Sponsor Report - September 2021 9/3/2021 Seg Sponsor Boro Highway Dir Location From Location To MM-F MM-T 209B 16th Street Cooperative dba Flatbush Food Co-op R Staten Island Expressway E Hanover Avenue Fingerboard Road Underpass 3067 3076 219 A & J Power Washing R Staten Island Expressway W Woolley Avenue Richmond Avenue Underpass 4037 4024 003 A & L Cesspool Service Corp. Q Grand Central Parkway W 27th Avenue Ped. Overpass 93rd Street 4040 4030 262 Adopt A Highway Maintenance Corporation of NY B Bruckner Expressway S Country Club Road CBE/Swinton Avenue 2063 2050 261 Adopt A Highway Maintenance Corporation of NY B Bruckner Expressway S Pelham Pkwy. On/Rmp. Country Club Road 2072 2063 169 Adopt A Highway Maintenance Corporation of NY B Throgs Neck Expressway S Randall Avenue Overpass Lawton Avenue 2006 2018 194 Adopt A Highway Maintenance Corporation of NY M Henry Hudson Parkway N 182nd Street Dyckman Street 1127 1138 194A Adopt A Highway Maintenance Corporation of NY M Henry Hudson Parkway N 182nd Street Dyckman Street 1127 1138 063 Adopt A Highway Maintenance Corporation of NY Q Clearview Expressway N Union Turnpike Ramp 53rd Avenue Overpass 1010 1021 343 Adopt A Highway Maintenance Corporation of NY R Korean War Veterans Parkway S Huguenot Avenue Maguire Avenue 2017 2007 033 AG Collision Center Inc. Q Jackie Robinson Parkway W Grand Central Parkway Overpass Metropolitan Avenue Underpass 4046 4037 112 Agape Luxury Corp. B Bronx River Parkway N East Fordham Road On Ramp Burke Avenue 1026 1035 111 Agape Luxury Corp. B Bronx River Parkway N Burke Avenue East 222nd Street 1035 1045 273 Agape Luxury Corp.