God and the Absolute in Vivekananda and Aurobindo- Contrasting Reactions to Contact with the West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo Ghosh

UNIT 6 HINDUISM : SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND SRI AUROBINDO GHOSH Structure 6.2 Renaissance of Hi~~duis~iiand the Role of Sri Raniakrishna Mission 0.3 Swami ViveItananda's Philosopliy of Neo-Vedanta 6.4 Swami Vivckanalida on Nationalism 6.4.1 S\varni Vivcknnnnda on Dcrnocracy 6.4.2 Swami Vivckanar~daon Social Changc 6.5 Transition of Hinduism: Frolii Vivekananda to Sri Aurobindo 6.5. Sri Aurobindo on Renaissance of Hinduism 6.2 Sri Aurol>i~ldoon Evil EffLrcls of British Rulc 6.6 S1.i Aurobindo's Critique of Political Moderates in India 6.6.1 Sri Aurobilido on the Essencc of Politics 6.6.2 SI-iAurobindo oil Nationalism 0.6.3 Sri Aurobindo on Passivc Resistance 6.6.4 Thcory of Passive Resistance 6.6.5 Mcthods of Passive Rcsistancc 6.7 Sri Aurobindo 011 the Indian Theory of State 6.7.1 .J'olitical ldcas of Sri Aurobindo - A Critical Study 6.8 Summary 1 h 'i 6.9 Exercises j i 6.1 INTRODUCTION In 19"' celitury, India camc under the British rule. Due to the spread of moder~ieducation and growing public activities, there developed social awakening in India. The religion of Hindus wns very harshly criticized by the Christian n?issionaries and the British historians but at ~hcsanie timc, researches carried out by the Orientalist scholars revealcd to the world, lhc glorioi~s'tiaadition of the Hindu religion. The Hindus responded to this by initiating reforms in thcir religion and by esfablishing new pub'lie associations to spread their ideas of refor111 and social development anlong the people. -

10 Religious Reform Movements in Modern India: the Ramakrishna Mission and Swami Vivekananda- Flexiprep

9/22/2021 Chapter – 10 Religious Reform Movements in Modern India: The Ramakrishna Mission and Swami Vivekananda- FlexiPrep FlexiPrep Chapter – 10 Religious Reform Movements in Modern India: The Ramakrishna Mission and Swami Vivekananda (For CBSE, ICSE, IAS, NET, NRA 2022) Get unlimited access to the best preparation resource for CBSE/Class-10 : get questions, notes, tests, video lectures and more- for all subjects of CBSE/Class-10. Attend a meeting of the Arya Samaj any day. They are also performing yajana and reading the scriptures. This was the basic contribution of Mool Shanker an important representative of the religious reform movement in India from Gujarat. He later came to be known as Dayanand Saraswathi. He founded the Arya Samaj in 1875. ©FlexiPrep. Report ©violations @https://tips.fbi.gov/ The most influential movement of religious and social reform in northern India was started by Dayanand Saraswathi. He held that the Vedas contained all the knowledge imparted to man by God and essentials of modern science could also be traced in them. 1 of 2 9/22/2021 Chapter – 10 Religious Reform Movements in Modern India: The Ramakrishna Mission and Swami Vivekananda- FlexiPrep He was opposed to idolatry, ritual and priesthood, particularly to the prevalent caste practices and popular Hinduism as preached by the Brahmins. He favoured the study of western science. With all this doctrine, he went about all over the country and in 1875 founded the Arya Samaj in Bombay. Satyarth Prakash was his most important book. The use of Hindi in his writings and preaching made his ideas accessible to the common people of northern India. -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

Vedanta's Message for Our Time: Man's Need for the Eternal

Vedanta’s Message For Our Time: Man’s Need For The Eternal Philosophy By Swami Tathagatananda Since the advent of Shri Ramakrishna on the spiritual horizon of mankind, a new epoch of spiritual fraternity had been steadily unfolding. The West has been evincing its keen interest in the ancient truth of India’s heritage. Shri Ramakrishna demonstrated the reality of Divinity by realizing the Truth in his own life. This re-authentication of the ancient truths in the life of Shri Ramakrishna is a great example of hope and inspiration. Shri Ramakrishna proclaimed the fundamental unity of all religions to a world plagued by hostility, disharmony and persecution, all in the name of religion. Swami Vivekananda broadcast that teaching to the world when religious truths and the subjects of God, Soul and immortality had lost their reality and made a mockery of religion. Various dogmatic theologies with their anti-rational and anti-humanistic attitudes had denigrated the image of religion, which was ultimately abandoned in the modern period. In that bleak, hostile world, Swami Vivekananda preached the sublime truth of Vedanta that speaks of man’s spiritual depth and dimension. He taught about a new image of man as potentially Divine. According to Marie Louise Burke, “As Swamiji later wrote to Swami Ramakrishnananda, ‘I am careering all over the country. Wherever the seed of his power will fall, there it will fructify—be it today, or in a hundred years.’ . Throughout his life, wherever he was and whatever he was outwardly doing, he permanently lifted the consciousness of all with whom he came in contact. -

Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire

Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire Volume III Word by word construing in Sanskrit and English of Selected ‘Hymns of the Atris’ from the Rig-veda Compiled By Mukund Ainapure i Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire Volume III Word by word construing in Sanskrit and English of Selected ‘Hymns of the Atris’ from the Rig-veda Compiled by Mukund Ainapure • Original Sanskrit Verses from the Rig Veda cited in The Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo Volume 16, Hymns to the Mystic Fire – Part II – Mandala 5 • Padpātha Sanskrit Verses after resolving euphonic combinations (sandhi) and the compound words (samās) into separate words • Sri Aurobindo’s English Translation matched word-by-word with Padpātha, with Explanatory Notes and Synopsis ii Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire – Volume III By Mukund Ainapure © Author All original copyrights acknowledged April 2020 Price: Complimentary for personal use / study Not for commercial distribution iii ॥ी अरिव)दचरणारिव)दौ॥ At the Lotus Feet of Sri Aurobindo iv Prologue Sri Aurobindo Sri Aurobindo was born in Calcutta on 15 August 1872. At the age of seven he was taken to England for education. There he studied at St. Paul's School, London, and at King's College, Cambridge. Returning to India in 1893, he worked for the next thirteen years in the Princely State of Baroda in the service of the Maharaja and as a professor in Baroda College. In 1906, soon after the Partition of Bengal, Sri Aurobindo quit his post in Baroda and went to Calcutta, where he soon became one of the leaders of the Nationalist movement. -

Sri Ramakrishna, Swami Vivekananda, and Hindu-Christian Dialogue

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 8 Article 5 January 1995 Sri Ramakrishna, Swami Vivekananda, and Hindu-Christian Dialogue Michael Stoeber Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Stoeber, Michael (1995) "Sri Ramakrishna, Swami Vivekananda, and Hindu-Christian Dialogue," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 8, Article 5. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1110 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Stoeber: Sri Ramakrishna, Swami Vivekananda, and Hindu-Christian Dialogue SRI RAMAKRISHNA, SWAl\II VIVEKANANDA, AND HINDU-CHRISTIAN DIALOGUE* Michael Stoeber The Catholic University of America IN THE LATE smnmer of 1993, noted for his interests in Buddhism, representatives of the major religions of the Sikhism, J ainism, Islam, and Christianity. world met in interfaith dialogue in Chicago, Indeed, his experiences of elements of these to celebrate the centenary of the 1893 different faiths led him to advocate a World's Parliament of Religions. The 1893 common divine Reality behind the many Parliament was remarkable, both in its forms of religiousness, despite the many magnitude and its purpose: it brought differences between traditions. He once together forty-one denominations and over commented, for example: four hundred men and women in a forum of A lake has several ghats [bathing mutual teaching and learning. -

9 Spiritual Development: Meaning and Purpose9

Huitt, W., & Robbins, J. (2018). Spiritual development: Meaning and purpose. In W. Huitt (Ed.), Becoming a Brilliant Star: Twelve core ideas supporting holistic education (pp. 159-178). La Vergne, TN: IngramSpark. Retrieved from http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/2018-09-huitt-robbins- brilliant-star-spiritual.pdf SPIRITUAL DEVELOPMENT 9 Spiritual Development: Meaning and Purpose9 William G. Huitt and Jennifer L. Robbins Spirituality is a difficult concept to define. While it has been explored throughout human history as one of the three fundamental aspects of human beings (ie, body, mind, spirit) (Huitt, 2010b), there is widespread disagreement as to its origin, functioning, or even importance (Huitt, 2000). However, in a broad perspective, spirituality deals fundamentally with how human beings approach the unknowns of life, how we define and relate to the sacred. Spirituality is considered by many psychologists to be an inherent property of the human being (Helminiak, 1996; Newberg, D’Aquili, & Rause, 2001). From this viewpoint, human spirituality is an attempt to understand and connect to the unknowns of the universe or search for meaningfulness in one’s life (Adler, 1980; Frankl, 1998). Likewise, Weaver and Cotrell (1992) proposed that spirituality “refers to matters of ultimate concern that call for releasing the passions of the soul to search for goals with personal meaning” (p. 1). Other definitions include a relationship with the sacred (Beck & Walters, 1977), “an individual's experience of and relationship with a fundamental, nonmaterial aspect of the universe” (Tolan, 2002). Others view soul or spirit as a description of the “vital principle or animating force believed to be within living beings” (Zinn, 1997, p. -

The Neo-Vedanta Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda

VEDA’S JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (JOELL) Vol.6 Issue 4 An International Peer Reviewed (Refereed) Journal 2019 Impact Factor (SJIF) 4.092 http://www.joell.in RESEARCH ARTICLE THE NEO-VEDANTA PHILOSOPHY OF SWAMI VIVEKANANDA Tania Baloria (Ph.D Research Scholar, Jaipur National University, Jagatpura, Jaipur.) doi: https://doi.org/10.33329/joell.64.19.108 ABSTRACT This paper aims to evaluate the interpretation of Swami Vivekananda‘s Neo-Vedanta philosophy.Vedanta is the philosophy of Vedas, those Indian scriptures which are the most ancient religious writings now known to the world. It is the philosophy of the self. And the self is unchangeable. It cannot be called old self and new self because it is changeless and ultimate. So the theory is also changeless. Neo- Vedanta is just like the traditional Vedanta interpreted with the perspective of modern man and applied in practical-life. By the Neo-Vedanta of Swami Vivekananda is meant the New-Vedanta as distinguished from the old traditional Vedanta developed by Sankaracharya (c.788 820AD). Neo-Vedantism is a re- establishment and reinterpretation Of the Advaita Vedanta of Sankara with modern arguments, in modern language, suited to modern man, adjusting it with all the modern challenges. In the later nineteenth century and early twentieth century many masters used Vedanta philosophy for human welfare. Some of them were Rajarammohan Roy, Swami DayanandaSaraswati, Sri CattampiSwamikal, Sri Narayana Guru, Rabindranath Tagore, Mahatma Gandhi, Sri Aurobindo, and Ramana Maharsi. Keywords: Female subjugation, Religious belief, Liberation, Chastity, Self-sacrifice. Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Copyright © 2019 VEDA Publications Author(s) agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License . -

An Appraisal

Adnan Tariq * Muhammad Iqbal Chawla ** FROM COMMUNITARIANISM TO COMMUNALISM, COMMUNITARIAN IDENTITY IN LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY LAHORE: AN APPRAISAL This paper attempts to understand the communitarian sense of awakening in the city of Lahore, which surfaced in the nineteenth century. This communal tangle further transformed into communal bigotry. By the end of the nineteenth century, Lahore had started witnessing the burgeoning communal antagonisms in its colonial inspired cosmopolitanism. Though Muslims were in significant majority, they were deprived in many of the important civic affairs. On the contrary, Hindus were far less in number but having par excellence in many of the socio-economic realm, had upper hand in the civic affairs. Sikhs were the least in numbers in the three-main communities in the colonial Lahore. Every community had grabbed the colonial opportunities according to their socio-economic status; that status-according grabbing resulted into disequilibrium among the communities. At the same time, all the three-main communities had tried to draw their communitarian identity according to the colonial challenges posed by missionaries, interacting and amplifying by the subsequent tussles even among themselves. In that foreground, the retrospective genesis of religious antagonism was transformed into the communitarian and subsequent communal antagonism in the city of Lahore with all of its own peculiarities. Assassination of Lala Lekh Ram testifies that Lahore had entered into the communal antagonism, which sealed the future course up to the coming of partition. Thus, it is indeed important to study the maneuverings of all the three major communities in the city of Lahore while making their identical schemes. -

Mother India

MOTHER INDIA MONTHLY REVIEW OF CULTURE Vol. LX No. 6 “Great is Truth and it shall prevail” CONTENTS Sri Aurobindo SELF (Poem) ... 421 THE SCIENCE OF CONSCIOUSNESS ... 422 The Mother ‘NO ERROR CAN PERSIST IN FRONT OF THEE’ ... 426 THE POWER OF WORDS ... 427 Amal Kiran (K. D. Sethna) “SAKUNTALA” AND “SAKUNTALA’S FAREWELL”—CORRESPONDENCE WITH SRI AUROBINDO ... 429 Priti Das Gupta MOMENTS, ETERNAL ... 435 Arun Vaidya AN ETERNAL DREAM ... 440 Prabhjot Kulkarni WHO AM I (Poem) ... 447 S. V. Bhatt PAINTING AS SADHANA: KRISHNALAL BHATT (1905-1990) ... 448 Narad (Richard Eggenberger) TEHMI-BEN—NARAD REMEMBERS ... 456 Sitangshu Chakrabortty LORD AND MOTHER NATURE (Poem) ... 464 Bibha Biswas THE BIRTH OF “BATIK WORK” ... 465 Prithwindra Mukherjee BANKIMCHANDRA CHATTERJEE ... 468 Chunilal Chowdhury A WORLD WITHOUT WAR ... 476 Prema Nandakumar DEVOTIONAL POETRY IN TAMIL ... 480 Pujalal NAVANIT STORIES ... 490 421 SELF He said, “I am egoless, spiritual, free,” Then swore because his dinner was not ready. I asked him why. He said, “It is not me, But the belly’s hungry god who gets unsteady.” I asked him why. He said, “It is his play. I am unmoved within, desireless, pure. I care not what may happen day by day.” I questioned him, “Are you so very sure?” He answered, “I can understand your doubt. But to be free is all. It does not matter How you may kick and howl and rage and shout, Making a row over your daily platter. “To be aware of self is liberty. Self I have got and, having self, am free.” SRI AUROBINDO (Collected Poems, SABCL, Vol. -

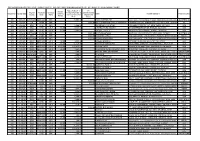

Foreign Contribution Report

SRI AUROBINDO ASHRAM TRUST PONDICHERRY FOREIGN CONTRIBUTION DONORS LIST OCTOBER-20 TO DECEMBER-20(Q3) Rupee Value of ( FC Foreign Original Payment Currency Foreign Chqs/ DDs & Donation(Cash) Receipt No F Receipt Date Currency Name Present Address-1 Present Country Country mode Name Currency Notes )1st (Rupees) 1st Amount Recp. Recpt 300 1-10-20 AUSTRALIA NEFT HDFC INR 5,308.00 RAJIV RATTAN DR GRATITUDE, 159 BOUNDARY ROAD, WAHROONGA, NSW-2076 AUSTRALIA 301 2-10-20 UK CASH INR 1,000.00 SRI AUROBINDO CIRCLE(ASHRAM) 8 SHERWOOD AVE., STREATHAM VALE, SW16 5EW, LONDON UK 302 2-10-20 USA CHQ INR 6,000.00 AURINDAK K GHATAK 455 MAIN STREET # 16F, NEW YORK, NY-10044 USA 303 2-10-20 USA CHQ US-$ 100.00 7,231.00 CHITRALEKHA GHOSH 22 INDEPENDENCE DR, EDISON, NJ-08820 USA 304 2-10-20 USA CHQ US-$ 101.00 7,303.00 SATISH J PATEL 1413 BRYS DR, GROSSE POINTE, MI-48236 USA 305 2-10-20 AUSTRALIA CASH INR 1,001.00 R VISWANATHAN UNIT-330, 298 SUSSEX ST, NSW-2000, SYDNEY AUSTRALIA 306 2-10-20 USA CASH INR 1,000.00 RICHARD HARTZ C/O GOLCONDE, 7 RUE DUPUY, PONDICHERRY-605001 INDIA 307 2-10-20 AUSTRALIA CASH INR 1,000.00 SUSAN CROTHERS C/O GOLCONDE, 7 RUE DUPUY, PONDICHERRY-605001 INDIA 308 2-10-20 INDIA NEFT HDFC US-$ 50.00 3,685.25 DINESH MANDAL 1013 ROYAL STOCK LN, CARY, NC-27513 USA 309 2-10-20 USA NEFT HDFC US-$ 205.00 15,127.46 VIJAYA CHINNADURAI 1739 STIFEL LANE DR, CHESTERFIELD, MO-63017 USA 310 3-10-20 USA NEFT HDFC US-$ 5,000.00 3,65,425.00 KUSUM PATEL 1694 HIDDEN OAK TRAIL,MANSFIELD, OH-44906 USA 311 3-10-20 INDIA NEFT HDFC US-$ 20.00 1,461.70 RAMAKRISHNAN -

In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury's

Bharatbhoomi Punyabhoomi: In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury’s Writings Author: Arkamitra Ghatak Stable URL: http://www.globalhistories.com/index.php/GHSJ/article/view/105 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/GHSJ.2017.105 Source: Global Histories, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Apr. 2017), pp. 39–61 ISSN: 2366-780X Copyright © 2017 Arkamitra Ghatak License URL: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Publisher information: ‘Global Histories: A Student Journal’ is an open-access bi-annual journal founded in 2015 by students of the M.A. program Global History at Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. ‘Global Histories’ is published by an editorial board of Global History students in association with the Freie Universität Berlin. Freie Universität Berlin Global Histories: A Student Journal Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut Koserstraße 20 14195 Berlin Contact information: For more information, please consult our website www.globalhistories.com or contact the editor at: [email protected]. Bharatbhoomi Punyabhoomi: In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury’s Writings ARKAMITRA GHATAK Arkamitra Ghatak completed her major in History at Presidency University, Kolkata, in 2016, securing the first rank in the order of merit and was awarded the Gold Medal for Academic Ex- cellence. She is currently pursuing a Master in History at Presidency University. Her research interests include intellectual history in its plural spatialities, expressions of feminine subjec- tivities and spiritualities, as well as articulations of power and piety in cultural performances, especially folk festivals. She has presented several research papers at international student seminars organized at Presidency University, Jadavpur University and other organizations.