Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Youth – Led Development of Tanzania`S Moringa Value Chain Project in Iringa and Mbeya Regions

Youth – Led Development of Tanzania`s Moringa Value Chain Project in Iringa and Mbeya regions Mapping and assessment report of the Moringa value chain in Tanzania January 2020 Mapping and assessment report of the Moringa value chain in Tanzania |Page 1 Preface This report has been developed by Farm Africa. It was made possible through support provided by Feed the Future through the U.S. Agency for International Development, under the Feed the Future Tanzania Advancing Youth activity, Contract No.AID-OAA-I-15-00014 Task Order No. AID-621-TO-17-00004. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development. Within the activity, Intermediate Result #1 has been to increase expertise and improved coordination among Moringa stakeholders through assessment and mapping the existing business models in Tanzania. The result of this exercise will inform future interventions within the value chain. In addition, this report is intended to investigate the characteristics of MSMEs in Moringa and to suggest ways of improving their performance, particularly tackling constraints faced by youth entrepreneurs. This report is a result of different collaborations created during the implementation of the project so a variety of methods were employed. Some of the information presented herein came from reviewing other documents (mentioned in reference chapter), but most of the information and photos presented in this report were collected during different stages of the project ie: meeting notes with 5 local government authorities, survey data from +160 producers (farmers), 10 processors, 1 aggregator and 2 traders in 5 regions using a structured questionnaire. -

2019 Tanzania in Figures

2019 Tanzania in Figures The United Republic of Tanzania 2019 TANZANIA IN FIGURES National Bureau of Statistics Dodoma June 2020 H. E. Dr. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli President of the United Republic of Tanzania “Statistics are very vital in the development of any country particularly when they are of good quality since they enable government to understand the needs of its people, set goals and formulate development programmes and monitor their implementation” H.E. Dr. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli the President of the United Republic of Tanzania at the foundation stone-laying ceremony for the new NBS offices in Dodoma December, 2017. What is the importance of statistics in your daily life? “Statistical information is very important as it helps a person to do things in an organizational way with greater precision unlike when one does not have. In my business, for example, statistics help me know where I can get raw materials, get to know the number of my customers and help me prepare products accordingly. Indeed, the numbers show the trend of my business which allows me to predict the future. My customers are both locals and foreigners who yearly visit the region. In June every year, I gather information from various institutions which receive foreign visitors here in Dodoma. With estimated number of visitors in hand, it gives me ample time to prepare products for my clients’ satisfaction. In terms of my daily life, Statistics help me in understanding my daily household needs hence make proper expenditures.” Mr. Kulwa James Zimba, Artist, Sixth street Dodoma.”. What is the importance of statistics in your daily life? “Statistical Data is useful for development at family as well as national level because without statistics one cannot plan and implement development plans properly. -

Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa

Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa: A Threat Assessment Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: +(43) (1) 26060-0, Fax: +(43) (1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org OrgAnIzed CrIme And Instability In CenTrAl AFrica A Threat Assessment United Nations publication printed in Slovenia October 2011 – 750 October 2011 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa A Threat Assessment Copyright © 2011, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Acknowledgements This study was undertaken by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA). Researchers Ted Leggett (lead researcher, STAS) Jenna Dawson (STAS) Alexander Yearsley (consultant) Graphic design, mapping support and desktop publishing Suzanne Kunnen (STAS) Kristina Kuttnig (STAS) Supervision Sandeep Chawla (Director, DPA) Thibault le Pichon (Chief, STAS) The preparation of this report would not have been possible without the data and information reported by governments to UNODC and other international organizations. UNODC is particularly thankful to govern- ment and law enforcement officials met in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda and Uganda while undertaking research. Special thanks go to all the UNODC staff members - at headquarters and field offices - who reviewed various sections of this report. The research team also gratefully acknowledges the information, advice and comments provided by a range of officials and experts, including those from the United Nations Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, MONUSCO (including the UN Police and JMAC), IPIS, Small Arms Survey, Partnership Africa Canada, the Polé Institute, ITRI and many others. -

Chamwino and Chemba Districts)

LOCAL INVESTMENT CLIMATE (LIC) REVENUE STUDIES FOR TWO LOCAL GOVERNMENT AUTHORITIES (CHAMWINO AND CHEMBA DISTRICTS) FINAL REPORT Dr. Victor George, Dr. Alex Kira, Mr. Elia John and Mr. Sunga Mabeja 11/08/2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................ i List of Tables .............................................................................................................................................. iii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ iii Acronyms .................................................................................................................................................... iv 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 1.1 Background to the Study ........................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Objective of the Study ................................................................................................................ 6 2.0 The Study Approach and Methodology ............................................................................ 8 2.1 Sampling Frame ......................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 -

African Development Bank United Republic of Tanzania

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA DODOMA CITY OUTER RING ROAD (110.2 km) CONSTRUCTION PROJECT APPRAISAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure RDGE/PICU DEPARTMENTS April 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. STRATEGIC THRUST AND JUSTIFICATIONS ............................................................................... 1 1.1 PROJECT LINKAGES WITH NATIONAL AND REGIONAL STRATEGIES ........................................................ 1 1.2 RATIONALE FOR BANK INVOLVEMENT .................................................................................................. 1 1.3 AID COORDINATION ............................................................................................................................. 2 II. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 PROJECT OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 PROJECT COMPONENTS ........................................................................................................................ 3 2.3 TECHNICAL SOLUTIONS ADOPTED AND ALTERNATIVES CONSIDERED .................................................... 3 2.4 PROJECT TYPE ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2.5 PROJECT COST AND FINANCING MECHANISMS ..................................................................................... -

A Contextual Analysis for Village Land Use Planning in Tanzania's

A contextual analysis for village land use planning in Tanzania’s Bagamoyo and Chalinze districts, Pwani region and Mvomero and Kilosa districts, Morogoro region Sustainable Rangeland Management Project ILRI PROJECT REPORT ISBN: 92-9146-586-0 The International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) works to improve food and nutritional security and reduce poverty in developing countries through research for efficient, safe and sustainable use of livestock. Co-hosted by Kenya and Ethiopia, it has regional or country offices and projects in East, South and Southeast Asia as well as Central, East, Southern and West Africa. ilri.org CGIAR is a global agricultural research partnership for a food-secure future. Its research is carried out by 15 research centres in collaboration with hundreds of partner organizations. cgiar.org A contextual analysis for village land use planning in Pwani and Morogoro regions of Tanzania i ii A contextual analysis for village land use planning in Pwani and Morogoro regions of Tanzania A contextual analysis for village land use planning in Tanzania’s Bagamoyo and Chalinze districts, Pwani region and Mvomero and Kilosa districts, Morogoro region Sustainable Rangeland Management Project Emmanuel Sulle and Wilbard Mkama Editor: Fiona Flintan (International Livestock Research Institute) July 2019 A contextual analysis for village land use planning in Pwani and Morogoro regions of Tanzania iii ©2019 International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) ILRI thanks all donors and organizations which globally support its work through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund This publication is copyrighted by the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). It is licensed for use under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. -

Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change and Variability on Maize Post-Harvest System at Kongwa and Kondoa District in Tanzania

Vol. 12(1), pp. 7-18, January-June 2020 DOI: 10.5897/JABSD2019.0360 Article Number: B80A0C563237 ISSN: 2141-2340 Copyright ©2020 Journal of Agricultural Biotechnology and Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/JABSD Sustainable Development Full Length Research Assessing the impacts of climate change and variability on maize post-harvest system at Kongwa and Kondoa District in Tanzania Namkunda Johnson1, Agnes Nyomora2 and James Lyimo3* 1Centre for Climate Change Studies, University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. 2Department of Botany, College of Natural Resources and Applied Sciences, University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. 3Institute of Resource Assessment, University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Received 11 October, 2019; Accepted 24 February, 2020 This study attempted to investigate the pattern and trend of climate change, its influence and interaction with maize post-harvest system and established the current status of maize post-harvest losses at Kongwa and Kondoa district in Tanzania. Participatory rural appraisal technique and household survey methods were used to collect primary data. Secondary data for the study area including rainfall and temperature data from the year 1982 -2017 were collected from Tanzania Meteorological Agency. Qualitative data were analyzed thematically using Nvivo software. Quantitative data from household survey were cross tabulated using SPSS software version 20 and the results were confirmed using canonical correlation test while pattern and trend of rainfall and temperature data were analyzed using trend lines and was confirmed using Mann-Kendall trend test. Findings indicated that annual temperature increase and monthly rainfall pattern changes influences maize post-harvest losses with significant losses denoted more during harvesting and storage with a positive correlation of R2= 0.014 and R2 = 0.121 respectively, while statuses for the maize post-harvest losses are below the threshold value of 40%. -

Uranium Contamination in Drinking Water and Foodstuffs in Bahi District, Central Tanzania

JCEE Volume 5 Issue 2 Uranium contamination in drinking water and foodstuffs in Bahi District, Central Tanzania Ernest M.M. Marwa1*, Zainab J. Mziray2, Bernard E. Chove2 and Abel K. Kaaya1 1Department of Soil Science, Sokoine University of Agriculture, P.O. Box 3008, Morogoro, Tanzania 2 Department of Food Science & Technology, Sokoine University of Agriculture, P.O. Box 3006, Morogoro, Tanzania *Corresponding author: [email protected]; Tel: +255 757 577351 Abstract A field survey was conducted in Bahi District in Central Tanzania to investigate uranium levels in drinking water and to evaluate its contamination in some foodstuffs as proxy to their safety for human and animal consumption. Regularly consumed cereal grains, cassava leaves, salt, soda ash, catfish, flamingo meat, surface and underground waters were randomly sampled in the district and analyzed using inductively coupled plasma - optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). The study found extremely high levels of uranium in surface and underground waters of up to 1233µg L-1, a value that exceeds the World Health Organization standard of 30 µg L-1 by a factor of 41. Soda ash, which is locally consumed and some is exported, had a very high value of 1910 µgU kg-1. Finger millet grains, catfish and flamingo had 32, 17.98 and 31.78 µgU kg-1, respectively, values that were higher than the natural background level of 14 µgU kg-1 found in some common foodstuffs by the European Food Safety Authority. It was concluded that drinking water and consuming foodstuffs with high levels of uranium is endangering human and animal life in Bahi District. -

Social-Economic Profile

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA PRESIDENT’S OFFICE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT KONGWA DISTRICT SOCIAL-ECONOMIC PROFILE District Executive Director, P.O Box 57, KONGWA. Tel: 026 2320537 Fax. 026 2320537 Email: [email protected] August, 2016 i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction This description comprises six chapters. The first chapter introduces the Council of Kongwa focusing on land, climatic condition, agro-ecological zones as well as its people. Kongwa ward is the seat of the District Headquarter. The town started as a centre for German Colonial activities in 1942 following establishment of groundnuts estates. The choice of its location strategically made to fertile soil suitable for groundnuts cultivation and accessibility to road. The town also has historical roots that associate it with the great Gogo tribe. Overtime, the town has redefined and extended its role, eventually becoming a centre for social and economic development for the hinterlands as a whole. The administrative area comprises a total of 22 wards, 87 villages, 383 suburbs and 2 township authorities. The distribution of wards include Sejeli, Kongwa, Sagara, Chamkoroma, Pandambili, Lenjulu, Chiwe, Kibaigwa, Mtanana, Njoge, Ngomai, Mkoka, Matongoro, Makawa, Chitego, Hogoro, Songambele, Zoissa, Iduo, Mlali, Nghumbi and Ugogoni. The District Economy The main economic activities in the council are farming, livestock keeping and informal sector activities. Overall, the industrial sector has been in a gradual development and scaling up their activities. This can be observed from small industries growing for processing cooking oil such as sunflower and groundnuts. This chapter covers the District GDP and average income (per capita), trade and cooperatives, annual budgeting, housing and unplanned settlements as well as informal sector. -

The Road to Total Sanitation: Notes from a Field Trip and Workshop on Scaling up in Africa

The Road to Total Sanitation: Notes from a field trip and workshop on scaling up in Africa The Road to Total Sanitation: Notes from a field trip and workshop on scaling up in Africa 23-24 July 2010 In July 2010, six organizations came together to study and discuss current prospects for scaling up access to sanitation and hygiene inVon East Africa. The group started with a trip to the field – visiting various projects in Tanzania that, between them, represent a range of approaches to improving access to sanitation and changing hygiene practices. The objective was not to evaluate or critique individual projects, but rather to look for overarching principles: what works; what doesn’t work; what are the gaps in our knowledge; how can working in partnership help us achieve our aims; what barriers do we need to overcome in order to extend the benefits of such projects to all people across Africa. These notes reflect the conclusions, recommendations and lessons learned from this trip. They are based on a two-day workshop that was held directly following the trip. Further detailed notes, photos, and video material can be found in the appendices. In addition, it is planned that various databanks of reports, photos and videos will be developed and made available via the web. In December 2009, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation organized a meeting on the topic of scaling up on-site sanitation. Following this meeting, WSP convened a meeting of partners to explore how issues raised at the Gates meeting could be taken forward in East Africa. -

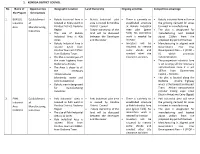

1. KONDOA DISTRICT COUNCIL No Name of the Project Opportunities

1. KONDOA DISTRICT COUNCIL No Name of Opportunities Geographic Location Land Ownership Ongoing activities Competitive advantage the Project for investors 1. BUKULU Establishment Bukulu Industrial Area is Bukulu Industrial plot There is currently no Bukulu Industrial Area will serve Industrial of Located at Soera ward in area is owned by Kondoa established structure the growing demand for areas Area Manufacturing Kondoa District, Dodoma District Council at Bukulu Industrial to invest in manufacturing Industries Region Future ownership of the Area plot (green The plot is designated for The size of Bukulu land will be discussed field). No demolition manufacturing and located Industrial Area is 400 between the Developer work is needed by about 220km from the Acres and the owner Investor proposed dry port of Ihumwa Bukulu Industrial Area is Investors will be Manufacturing is aligned with located 47km from required to remove Government Five Year Kondoa Town and 197km some shrubs and Development Plan – II (FYDP – from Dodoma Town. conduct other site II) which promotes The Plot is located just off clearance activities industrialisation the main highway from The prospective Industrial Area Dodoma to Arusha is set to enjoy all the necessary The Area is closer to all infrastructures since it is just the necessary 197km from Government infrastructures Capital – Dodoma (electricity, water and The plot is located along the communications) Dodoma – Arusha highway Bukulu area is designated which is the longest and busiest for manufacturing Trans – African transportation Industries corridor linking Cape Town (South Africa) and Cairo (Egypt) 2. PAHI Establishment Pahi Industrial Area is Pahi Industrial plot area There is currently no Pahi Industrial Area will serve Industrial of Located at Pahi ward in is owned by Kondoa established structure the growing demand for areas Area Manufacturing Kondoa District, Dodoma District Council at Pahi Industrial Area to invest in manufacturing Region plot (green field). -

Knowledge of Obstetric Danger Signs Among Recently-Delivered Women in Chamwino District, Tanzania: a Cross-Sectional Study Deogratius Bintabara1,2*, Rose N

Bintabara et al. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2017) 17:276 DOI 10.1186/s12884-017-1469-3 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Knowledge of obstetric danger signs among recently-delivered women in Chamwino district, Tanzania: a cross-sectional study Deogratius Bintabara1,2*, Rose N. M. Mpembeni3 and Ahmed Abade Mohamed4 Abstract Background: Low knowledge of danger signs has been shown to delay seeking obstetric care which leads to high maternal mortality and morbidity worldwide. In Tanzania about half of pregnant women are informed about obstetric danger signs during antenatal care, but the proportion of those who have full knowledge of these obstetric danger signs is not known. This study assessed the knowledge of obstetric danger signs and its associated factors among recently-delivered women in Chamwino District, Tanzania. Methods: A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in January 2014 in Chamwino District, Tanzania. A woman was considered knowledgeable if she spontaneously mentioned at least five danger signs in any of the three phases of childbirth (pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum) with at least one in each phase. Multistage cluster sampling was used to recruit study participants. Descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to control for confounding and other important covariates. Results: A total of 428 women were interviewed. The median age (IQR) was 26.5 (22–33) years. Only 25.2% of respondents were knowledgeable about obstetric danger signs during pregnancy, childbirth/labour and postpartum. Significant explanatory variables of being knowledgeable about obstetric danger signs were found to be maternal education (AOR = 1.96; 95% CI: 1.01, 3.82), maternal occupation (AOR = 2.23; 95% CI; 1.10, 4.52), spouse occupation (AOR = 2.10; 95% CI: 1.02, 4.32) and counseling on danger signs (AOR = 3.42; 95% CI: 1.36, 8.62) after controlling for the clustering effect, confounding and important covariates.