Implementing a Hybrid SRAM / Edram NUCA Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Error Detection and Correction Methods for Memories Used in System-On-Chip Designs

International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology (IJEAT) ISSN: 2249 – 8958, Volume-8, Issue-2S2, January 2019 Error Detection and Correction Methods for Memories used in System-on-Chip Designs Gunduru Swathi Lakshmi, Neelima K, C. Subhas ABSTRACT— Memory is the basic necessity in any SoC Static Random Access Memory (SRAM): It design. Memories are classified into single port memory and consists of a latch or flipflop to store each bit of multiport memory. Multiport memory has ability to source more memory and it does not required any refresh efficient execution of operation and high speed performance operation. SRAM is mostly used in cache memory when compared to single port. Testing of semiconductor memories is increasing because of high density of current in the and in hand-held devices. It has advantages like chips. Due to increase in embedded on chip memory and memory high speed and low power consumption. It has density, the number of faults grow exponentially. Error detection drawback like complex structure and expensive. works on concept of redundancy where extra bits are added for So, it is not used for high capacity applications. original data to detect the error bits. Error correction is done in Read Only Memory (ROM): It is a non-volatile memory. two forms: one is receiver itself corrects the data and other is It can only access data but cannot modify data. It is of low receiver sends the error bits to sender through feedback. Error detection and correction can be done in two ways. One is Single cost. Some applications of ROM are scanners, ID cards, Fax bit and other is multiple bit. -

Embedded DRAM

Embedded DRAM Raviprasad Kuloor Semiconductor Research and Development Centre, Bangalore IBM Systems and Technology Group DRAM Topics Introduction to memory DRAM basics and bitcell array eDRAM operational details (case study) Noise concerns Wordline driver (WLDRV) and level translators (LT) Challenges in eDRAM Understanding Timing diagram – An example References Slide 1 Acknowledgement • John Barth, IBM SRDC for most of the slides content • Madabusi Govindarajan • Subramanian S. Iyer • Many Others Slide 2 Topics Introduction to memory DRAM basics and bitcell array eDRAM operational details (case study) Noise concerns Wordline driver (WLDRV) and level translators (LT) Challenges in eDRAM Understanding Timing diagram – An example Slide 3 Memory Classification revisited Slide 4 Motivation for a memory hierarchy – infinite memory Memory store Processor Infinitely fast Infinitely large Cycles per Instruction Number of processor clock cycles (CPI) = required per instruction CPI[ ∞ cache] Finite memory speed Memory store Processor Finite speed Infinite size CPI = CPI[∞ cache] + FCP Finite cache penalty Locality of reference – spatial and temporal Temporal If you access something now you’ll need it again soon e.g: Loops Spatial If you accessed something you’ll also need its neighbor e.g: Arrays Exploit this to divide memory into hierarchy Hit L2 L1 (Slow) Processor Miss (Fast) Hit Register Cache size impacts cycles-per-instruction Access rate reduces Slower memory is sufficient Cache size impacts cycles-per-instruction For a 5GHz -

Semiconductor Memories

Semiconductor Memories Prof. MacDonald Types of Memories! l" Volatile Memories –" require power supply to retain information –" dynamic memories l" use charge to store information and require refreshing –" static memories l" use feedback (latch) to store information – no refresh required l" Non-Volatile Memories –" ROM (Mask) –" EEPROM –" FLASH – NAND or NOR –" MRAM Memory Hierarchy! 100pS RF 100’s of bytes L1 1nS SRAM 10’s of Kbytes 10nS L2 100’s of Kbytes SRAM L3 100’s of 100nS DRAM Mbytes 1us Disks / Flash Gbytes Memory Hierarchy! l" Large memories are slow l" Fast memories are small l" Memory hierarchy gives us illusion of large memory space with speed of small memory. –" temporal locality –" spatial locality Register Files ! l" Fastest and most robust memory array l" Largest bit cell size l" Basically an array of large latches l" No sense amps – bits provide full rail data out l" Often multi-ported (i.e. 8 read ports, 2 write ports) l" Often used with ALUs in the CPU as source/destination l" Typically less than 10,000 bits –" 32 32-bit fixed point registers –" 32 60-bit floating point registers SRAM! l" Same process as logic so often combined on one die l" Smaller bit cell than register file – more dense but slower l" Uses sense amp to detect small bit cell output l" Fastest for reads and writes after register file l" Large per bit area costs –" six transistors (single port), eight transistors (dual port) l" L1 and L2 Cache on CPU is always SRAM l" On-chip Buffers – (Ethernet buffer, LCD buffer) l" Typical sizes 16k by 32 Static Memory -

SRAM Edram DRAM

Technology Challenges and Directions of SRAM, DRAM, and eDRAM Cell Scaling in Sub- 20nm Generations Jai-hoon Sim SK hynix, Icheon, Korea Outline 1. Nobody is perfect: Main memory & cache memory in the dilemma in sub-20nm era. 2. SRAM Scaling: Diet or Die. 6T SRAM cell scaling crisis & RDF problem. 3. DRAM Scaling: Divide and Rule. Unfinished 1T1C DRAM cell scaling and its technical direction. 4. eDRAM Story: Float like a DRAM & sting like a SRAM. Does logic based DRAM process work? 5. All for one. Reshaping DRAM with logic technology elements. 6. Conclusion. 2 Memory Hierarchy L1$ L2$ SRAM Higher Speed (< few nS) Working L3$ Better Endurance eDRAM Memory (>1x1016 cycles) Access Speed Access Stt-RAM Main Memory DRAM PcRAM ReRAM Lower Speed Bigger Size Storage Class Memory NAND Density 3 Technologies for Cache & Main Memories SRAM • 6T cell. • Non-destructive read. • Performance driven process Speed technology. eDRAM • Always very fast. • 1T-1C cell. • Destructive read and Write-back needed. • Leakage-Performance compromised process technology. Standby • Smaller than SRAM and faster than Density Power DRAM. DRAM • 1T-1C cell. • Destructive read and Write-back needed. • Leakage control driven process technology. • Not always fast. • Smallest cell and lowest cost per bit. 4 eDRAM Concept: Performance Gap Filler SRAM 20-30X Cell Size Cell eDRAM DRAM 50-100X Random Access Speed • Is there any high density & high speed memory solution that could be 100% integrated into logic SoC? 5 6T-SRAM Cell Operation VDD WL WL DVBL PU Read PG SN SN WL Icell PD BL VSS BL V SN BL BL DD SN PD Read Margin: Write PG PG V Write Margin: SS PU Time 6 DRAM’s Charge Sharing DVBL VS VBL Charge Sharing Write-back VPP WL CS CBL V BL DD 1 SN C V C V C C V S DD B 2 DD S B BL 1/2VDD Initial Charge After Charge Sharing DVBL T d 1 1 V BL SS DVBL VBL VBL VDD 1 CB / CS 2 VBBW Time 1 1 I t L RET if cell leakage included Cell select DVBL VDD 1 CB / CS 2 CS 7 DRAM Scalability Metrics BL Cell WL CS • Cell CS. -

Digital Recorded Announcement Machine DRAM and EDRAM Guide

297-1001-527 DMS-100 Family Digital Recorded Announcement Machine DRAM and EDRAM Guide BASE09 and up Standard 13.06 August 1999 DMS-100 Family Digital Recorded Announcement Machine DRAM and EDRAM Guide Publication number: 297-1001-527 Product release: BASE09 and up Document release: Standard 13.06 Date: August 1999 1982, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1990, 1991, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1999 Northern Telecom All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America NORTHERN TELECOM CONFIDENTIAL: The information contained in this document is the property of Northern Telecom. Except as specifically authorized in writing by Northern Telecom, the holder of this document shall keep the information contained herein confidential and shall protect same in whole or in part from disclosure and dissemination to third parties and use same for evaluation, operation, and maintenance purposes only. Information is subject to change without notice. Northern Telecom reserves the right to make changes in design or components as progress in engineering and manufacturing may warrant. This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class A digital device pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules, and the radio interference regulations of the Canadian Department of Communications. These limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against harmful interference when the equipment is operated in a commercial environment. This equipment generates, uses and can radiate radio frequency energy and, if not installed and used in accordance with the instruction manual, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. Operation of this equipment in a residential area is likely to cause harmful interference in which case the user will be required to correct the interference at the user’s own expense. -

Introduction to Advanced Semiconductor Memories

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO ADVANCED SEMICONDUCTOR MEMORIES 1.1. SEMICONDUCTOR MEMORIES OVERVIEW The goal of Advanced Semiconductor Memories is to complement the material already covered in Semiconductor Memories. The earlier book covered the fol- lowing topics: random access memory technologies (SRAMs and DRAMs) and their application to specific architectures; nonvolatile technologies such as the read-only memories (ROMs), programmable read-only memories (PROMs), and erasable PROMs in both ultraviolet erasable (UVPROM) and electrically erasable (EEPROM) versions; memory fault modeling and testing; memory design for testability and fault tolerance; semiconductor memory reliability; semiconductor memories radiation effects; advanced memory technologies; and high-density memory packaging technologies [1]. This section provides a general overview of the semiconductor memories topics that are covered in Semiconductor Memories. In the last three decades of semiconductor memories' phenomenal growth, the DRAMs have been the largest volume volatile memory produced for use as main computer memories because of their high density and low cost per bit advantage. SRAM densities have generally lagged a generation behind the DRAM. However, the SRAMs offer low-power consumption and high-per- formance features, which makes them practical alternatives to the DRAMs. Nowadays, a vast majority of SRAMs are being fabricated in the NMOS and CMOS technologies (and a combination of two technologies, also referred to as the mixed-MOS) for commodity SRAMs. 1 2 INTRODUCTION TO ADVANCED SEMICONDUCTOR MEMORIES MOS Memory Market ($M) Non-Memory IC Market ($M) Memory % of Total IC Market 300,000 40% 250,000 30% 200,00U "o Q 15 150,000 20% 2 </> a. o 100,000 2 10% 50,000 0 0% 96 97 98 99 00 01* 02* 03* 04* 05* MOS Memory Market ($M) 36,019 29,335 22,994 32,288 49,112 51,646 56,541 70,958 94,541 132,007 Non-Memory IC Market ($M) 78,923 90,198 86,078 97,930 126,551 135,969 148,512 172,396 207,430 262,172 Memory % of Total IC Market 31% . -

A Survey of Architectural Approaches for Managing Embedded DRAM and Non-Volatile On-Chip Caches Sparsh Mittal, Jeffrey S

A Survey Of Architectural Approaches for Managing Embedded DRAM and Non-volatile On-chip Caches Sparsh Mittal, Jeffrey S. Vetter, Dong Li To cite this version: Sparsh Mittal, Jeffrey S. Vetter, Dong Li. A Survey Of Architectural Approaches for Managing Embedded DRAM and Non-volatile On-chip Caches. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2015, pp.14. 10.1109/TPDS.2014.2324563. hal-01102387 HAL Id: hal-01102387 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01102387 Submitted on 12 Jan 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. This is the author's version of an article that has been published in this journal. Changes were made to this version by the publisher prior to publication. The final version of record is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TPDS.2014.2324563 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PARALLEL AND DISTRIBUTING SYSTEMS 1 A Survey Of Architectural Approaches for Managing Embedded DRAM and Non-volatile On-chip Caches Sparsh Mittal, Member, IEEE, Jeffrey S. Vetter, Senior Member, IEEE, and Dong Li Abstract—Recent trends of CMOS scaling and increasing number of on-chip cores have led to a large increase in the size of on- chip caches. -

EDRAM Memory Controller for the TMS320C31 DSP Application Report

EDRAMtMemory Controller for the TMS320C31 DSP Application Report 1998 Digital Signal Processor Solutions Printed in U.S.A., January 1998 SPRA172 t EDRAM Memory Controller for the TMS320C31 DSP Enhanced Memory Systems 1850 Ramtron Drive, Colorado Springs, CO 80921 web: http://www.edram.com SPRA172 January 1998 Printed on Recycled Paper IMPORTANT NOTICE Texas Instruments (TI) reserves the right to make changes to its products or to discontinue any semiconductor product or service without notice, and advises its customers to obtain the latest version of relevant information to verify, before placing orders, that the information being relied on is current. TI warrants performance of its semiconductor products and related software to the specifications applicable at the time of sale in accordance with TI’s standard warranty. Testing and other quality control techniques are utilized to the extent TI deems necessary to support this warranty. Specific testing of all parameters of each device is not necessarily performed, except those mandated by government requirements. Certain applications using semiconductor products may involve potential risks of death, personal injury, or severe property or environmental damage (“Critical Applications”). TI SEMICONDUCTOR PRODUCTS ARE NOT DESIGNED, INTENDED, AUTHORIZED, OR WARRANTED TO BE SUITABLE FOR USE IN LIFE-SUPPORT APPLICATIONS, DEVICES OR SYSTEMS OR OTHER CRITICAL APPLICATIONS. Inclusion of TI products in such applications is understood to be fully at the risk of the customer. Use of TI products in such applications requires the written approval of an appropriate TI officer. Questions concerning potential risk applications should be directed to TI through a local SC sales office. In order to minimize risks associated with the customer’s applications, adequate design and operating safeguards should be provided by the customer to minimize inherent or procedural hazards. -

An Hybrid Edram/SRAM Macrocell to Implement First-Level Data Caches

An Hybrid eDRAM/SRAM Macrocell to Implement First-Level Data Caches Alejandro Valero1, Julio Sahuquillo1, Salvador Petit1, Vicente Lorente1, Ramon Canal2, Pedro López1, José Duato1 1Dpto. de Informática de Sistemas y Computadores 2Department of Computer Architecture Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Valencia, Spain Barcelona, Spain alvabre@fiv.upv.es [email protected] {jsahuqui, spetit, vlorente, plopez, jduato}@disca.upv.es ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION SRAM and DRAM cells have been the predominant technologies Static Random Access Memories (SRAM) and dynamic RAM used to implement memory cells in computer systems, each one (DRAM) have been the predominant technologies used to imple- having its advantages and shortcomings. SRAM cells are faster ment memory cells in computer systems. SRAM cells, typically and require no refresh since reads are not destructive. In contrast, implemented with six transistors (6T cells) have been usually de- DRAM cells provide higher density and minimal leakage energy signed for speed, while DRAM cells, implemented with only one since there are no paths within the cell from Vdd to ground. Re- capacitor and the corresponding pass transistor (1T1C cells) have cently, DRAM cells have been embedded in logic-based technol- been generally designed for density. Because of this reason, the for- ogy, thus overcoming the speed limit of typical DRAM cells. mer technology has been used to implement cache memories and In this paper we propose an n-bit macrocell that implements the latter for main memory storage. one static cell, and n-1 dynamic cells. This cell is aimed at being Cache memories occupy an important percentage of the overall used in an n-way set-associative first-level data cache. -

High-Performance Architectures for Embedded Memory Systems

High-Performance Architectures for Embedded Memory Systems Christoforos E. Kozyrakis Computer Science Division University of California, Berkeley [email protected] http://iram.cs.berkeley.edu/ Embedded DRAM systems roadmap This presentation Previous talks Desktop Laptop 32 MB Network Computer Camera/Phone 8 MB Video Games Graphics/Disks 2 MB Christoforos E. Kozyrakis ICCAD’98, Embedded Memory Tutorial Page 2 U.C. Berkeley Outline • Overview of general-purpose processors today • Future processor applications & requirements • Advantages and challenges of processor-DRAM integration • Future microprocessor architectures – characteristics and features – compatibility and interaction with embedded DRAM technology • Comparisons and conclusions Christoforos E. Kozyrakis ICCAD’98, Embedded Memory Tutorial Page 3 U.C. Berkeley Current state-of-the-art processors (1) • High performance processors – 64-bit operands, wide instruction issue (3-4) – dynamic scheduling, out-of-order execution, speculation – large multi-level caches – support for parallel systems – optimized for technical and/or commercial workloads – SIMD multimedia extensions (VIS, MAX, MMX, MDMX, Altivec) – 200 to 600 MHz, 20 to 80 Watts, 200 to 300 sq. mm – e.g. MIPS R10K, Pentium II, Alpha 21264, Sparc III Christoforos E. Kozyrakis ICCAD’98, Embedded Memory Tutorial Page 4 U.C. Berkeley Current state-of-the-art processors (2) • Embedded processors – 32/64-bit, single/dual issue, in-order execution – single-level (small) caches – code density improvements (Thump/MIPS16) – DSP/SIMD support – integrated I/O and memory controllers – some on-chip DRAM (up to 4MB) – optimized for low power, price/performance, MIPS/Watt – 50 to 250MHz, 0.3 to 4 Watts, 10 to 100 sq. mm – e.g. -

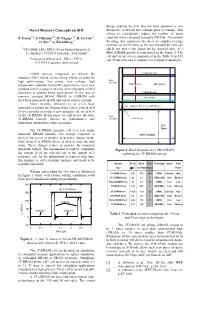

Novel Memory Concepts on SOI Destructive to Decode the Columns Prior to Sensing

design exploits the fact that the read operation is non Novel Memory Concepts on SOI destructive to decode the columns prior to sensing. This allows to considerably reduce the number of sense P. Fazan 1,2, S. Okhonin 1,2, M. Nagoga 1,2, R. Ferrant 2, amplifier when compared to regular DRAMs. The column O. Rey 2, A. Borschberg 2 decoding also suppresses the need of complex twisting schemes for the bit lines as the non decoded bit lines can 1STI, IMM, LEG, EPFL (Swiss Federal Institute of shield and protect the signal on the decoded ones. A 1 Technology), CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland Mbit eDRAM module is represented in the Figure 2. The 2 cell and circuit area is summarized in the Table 1 for 130 Innovative Silicon S.A., PSE-C, EPFL, and 90 nm rules and is compared to existing technologies. CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland Column Decoder CMOS devices integrated on Silicon On Insulator (SOI) wafers are becoming widely accepted for Row high performance, low power, low voltage, high Decoders temperature, radiation hard or RF applications. Up to now LBL (Metal 1) GBL (metal 3) standard active or passive devices were integrated on SOI Column Decoder substrates to address those applications. In the area of memory, standard SRAM, DRAM, or EEPROM cells WL (metal2) have been integrated on SOI and can be used as on bulk. More recently, Okhonin et al. [1,2] have Sense amplifiers, References and IO buffers proposed to exploit the floating body effects seen in SOI devices in order to realize a new memory cell, referred to as the 1T-DRAM. -

An Overview of DRAM-Based Security Primitives

cryptography Article An Overview of DRAM-Based Security Primitives Nikolaos Athanasios Anagnostopoulos 1 ID , Stefan Katzenbeisser 1, John Chandy 2 ID and Fatemeh Tehranipoor 3,∗ ID 1 Computer Science Department, Technical University of Darmstadt, Mornewegstraße 32, S4|14, 64293 Darmstadt, Germany; [email protected] (N.A.A.); [email protected] (S.K.) 2 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Connecticut, 371 Fairfield Way, U-4157, Storrs, CT 06269-4157, USA; [email protected] 3 School of Engineering, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94132, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-415-338-7821 Received: 25 February 2018; Accepted: 26 March 2018; Published: 28 March 2018 Abstract: Recent developments have increased the demand for adequate security solutions, based on primitives that cannot be easily manipulated or altered, such as hardware-based primitives. Security primitives based on Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) can provide cost-efficient and practical security solutions, especially for resource-constrained devices, such as hardware used in the Internet of Things (IoT), as DRAMs are an intrinsic part of most contemporary computer systems. In this work, we present a comprehensive overview of the literature regarding DRAM-based security primitives and an extended classification of it, based on a number of different criteria. In particular, first, we demonstrate the way in which DRAMs work and present the characteristics being exploited for the implementation of security primitives. Then, we introduce the primitives that can be implemented using DRAM, namely Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs) and True Random Number Generators (TRNGs), and present the applications of each of the two types of DRAM-based security primitives.