Four - Survey Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife; Threatened and Endangered Species

2009 SNF Monitoring and Evaluation Report Wildlife; Threatened and Endangered Species Introduction The data described in this report outlines the history, actions, procedures, and direction that the Superior National Forest (aka the Forest or SNF) has implemented in support of the Gray Wolf Recovery Plan and Lynx Conservation Assessment and Strategy (LCAS). The Forest contributes towards the conservation and recovery of the two federally listed threatened and endangered species: Canada lynx and gray wolf, through habitat and access management practices, collaboration with other federal and state agencies, as well as researchers, tribal bands and non-governmental partners. Canada lynx On 24 March 2000, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service designated the Canada lynx a “Threatened” species in the lower 48 states. From 2004-2009 the main sources of information about Canada lynx for the SNF included the following: • Since 2003 the Canada lynx study has been investigating key questions needed to contribute to the recovery and conservation of Canada lynx in the Western Great Lakes. Study methods are described in detail in the annual study progress report available online at the following address: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/lynx/ . These methods have included collecting information on distribution, snow tracking lynx, tracking on the ground and in the air radio-collared lynx, studying habitat use, collecting and analyzing genetic samples (for example, from hair or scat) and conducting pellet counts of snowshoe hare (the primary prey). • In 2006 permanent snow tracking routes were established across the Forest. The main objective is to maintain a standardized, repeatable survey to monitor lynx population indices and trends. -

Eurasian Lynx – Your Essential Brief

Eurasian lynx – Your essential brief Background Q: Are lynx native to Britain? A: Based on archaeological evidence, the range of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) included Britain until at least 1,300 years ago. It is difficult to be precise about when or why lynx became extinct here, but it was almost certainly related to human activity – deforestation removed their preferred habitat, and also that of their prey, thus reducing prey availability. These declines in prey species may have been exacerbated by human hunting. Q: Where do they live now? A: Across Europe, Scandinavia, Russia, northern China and Southeast Asia. The range used to include other areas of Western Europe, including Britain, where they are no longer present. Q: How many are there? A: There are thought to be around 50,000 in the world, of which 9,000 – 10,000 live in Europe. They are considered to be a species of least concern by the IUCN. Modern range of the Eurasian lynx Q: How big are they? A: Lynx are on average around 1m in length, 75cm tall and around 20kg, with the males being slightly larger than the females. They can live to 15 years old, but this is rare in the wild. Q: What do they eat? A: The preferred prey of the lynx are the smaller deer species, primarily the roe deer. Lynx may also prey upon other deer species, including chamois, sika deer, smaller red deer, muntjac and fallow deer. Q: Do they eat other things? A: Yes. Lynx prey on many other species when their preferred prey is scarce, including rabbits, hares, foxes, wildcats, squirrel, pine marten, domestic pets, sheep, goats and reared gamebirds. -

Status of Large Carnivores in Serbia

Status of large carnivores in Serbia Duško Ćirović Faculty of Biology University of Belgrade, Belgrade Status and threats of large carnivores in Serbia LC have differend distribution, status and population trends Gray wolf Eurasian Linx Brown Bear (Canis lupus) (Lynx lynx ) (Ursus arctos) Distribution of Brown Bear in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Brown Bear in Serbia Dinaric-Pindos: Distribution 10000 km2 N=100-120 Population increase Range expansion Carpathian East Balkan: Distribution 1400 km2 Dinaric-Pindos N= a few East Balkan Population trend: unknown Carpathian: Distribution 8200 km2 N=8±2 Population stable Legal status of Brown Bear in Serbia According Law on Protection of Nature and the Law on Game and Hunting brown bear in Serbia is strictly protected species. He is under the centralized jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environmental Protection Treats of Brown Bear in Serbia Intensive forestry practice and infrastructure development . Illegal killing Low acceptance due to fear for personal safety Distribution of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Dinaric-Balkan: 2 Carpathian Distribution cca 43500 km N=800-900 Population - stabile/slight increasingly Dinaric Range - slight expansion Carpathian: Distribution 480 km2 (was) Population – a few Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian population is still undefined Carpathian Peri-Carpathian Legal status of Gray wolf in Serbia According the Law on Game and Hunting the gray wolf in majority pars of its distribution (south from Sava and Danube rivers) is game species with closing season from April 15th to July 1st. -

Bushmeat Hunting and Extinction Risk to the World’S Rsos.Royalsocietypublishing.Org Mammals

Downloaded from http://rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on October 26, 2017 Bushmeat hunting and extinction risk to the world’s rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org mammals 1,2 4,5 Research William J. Ripple , Katharine Abernethy , Matthew G. Betts1,2, Guillaume Chapron6, Cite this article: Ripple WJ et al.2016 Bushmeat hunting and extinction risk to the Rodolfo Dirzo7, Mauro Galetti8,9, Taal Levi1,2,3, world’s mammals R. Soc. open sci. 3: 160498. 10,11 12 http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160498 Peter A. Lindsey , David W. Macdonald , Brian Machovina13, Thomas M. Newsome1,14,15,16, Carlos A. Peres17, Arian D. Wallach18, Received: 10 July 2016 Accepted: 20 September 2016 Christopher Wolf1,2 and Hillary Young19 1GlobalTrophic Cascades Program, Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, 2Forest Biodiversity Research Network, Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, and 3Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Subject Category: OR 97331, USA Biology (whole organism) 4School of Natural Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, UK 5Institut de Recherche en Ecologie Tropicale, CENAREST, BP 842 Libreville, Gabon Subject Areas: 6Grimsö Wildlife Research Station, Department of Ecology, Swedish University of ecology Agricultural Sciences, 73091 Riddarhyttan, Sweden 7Department of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA Keywords: 8Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Instituto Biociências, Departamento de wild meat, bushmeat, hunting, mammals, Ecologia, 13506-900 Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brazil extinction 9Department of Bioscience, Ecoinformatics and Biodiversity, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark 10Panthera, 8 West 40th Street, 18th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA 11 Author for correspondence: Mammal Research Institute, Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of William J. -

Black Bear Ecology Life Systems – Interactions Within Ecosystems a Guide for Grade 7 Teachers

BEAR WISE Black Bear Ecology Life Systems – Interactions Within Ecosystems A Guide for Grade 7 Teachers Ministry of Natural Resources BEAR WISE Introduction Welcome to Black Bear Ecology, Life Systems – Interactions Within Ecosystems, a Guide for Grade 7 Teachers. With a focus on the fascinating world of black bears, this program provides teachers with a classroom ready resource. Linked to the current Science and Technology curriculum (Life Systems strand), the Black Bear Ecology Guide for teachers includes: I background readings on habitats, ecosystems and the species within; food chains and food webs; ecosystem change; black bear habitat needs and ecology and bear-human interactions; I unit at a glance; I four lesson plans and suggested activities; I resources including a glossary; list of books and web sites and information sheets about black bears. At the back of this booklet, you will find a compact disk. It includes in Portable Document Format (PDF) the English and French versions of this Grade 7 unit; the Grades 2 and 4 units; the information sheets and the Are You Bear Wise? eBook (2005). This program aims to generate awareness about black bears – their biological needs; their behaviour and how human action influences bears. It is an initiative of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. BEAR WISE Acknowledgements The Ministry of Natural Resources would like to thank the following people for their help in developing the Black Bear Ecology Education Program. This education program would not have been possible without their contributions -

Arabian Tahr in Oman Paul Munton

Arabian Tahr in Oman Paul Munton Arabian tahr are confined to Oman, with a population of under 2000. Unlike other tahr species, which depend on grass, Arabian tahr require also fruits, seeds and young shoots. The areas where these can be found in this arid country are on certain north-facing mountain slopes with a higher rainfall, and it is there that reserves to protect this tahr must be made. The author spent two years in Oman studying the tahr. The Arabian tahr Hemitragus jayakari today survives only in the mountains of northern Oman. A goat-like animal, it is one of only three surviving species of a once widespread genus; the other two are the Himalayan and Nilgiri tahrs, H. jemlahicus and H. hylocrius. In recent years the government of the Sultanate of Oman has shown great interest in the country's wildlife, and much conservation work has been done. From April 1976 to April 1978 I was engaged jointly by the Government, WWF and IUCN on a field study of the tahr's ecology, and in January 1979 made recommendations for its conservation, which were presented to the Government. Arabian tahr differ from the other tahrs in that they feed selectively on fruits, seeds and young shoots as well as grass. Their optimum habitat is found on the north-facing slopes of the higher mountain ranges of northern Oman, where they use all altitudes between sea level and 2000 metres. But they prefer the zone between 1000 and 1800m where the vegetation is especially diverse, due to the special climate of these north-facing slopes, with their higher rainfall, cooler temperatures, and greater shelter from the sun than in the drought conditions that are otherwise typical of this arid zone. -

Lynx, Felis Lynx, Predation on Red Foxes, Vulpes Vulpes, Caribou

Lynx, Fe/is lynx, predation on Red Foxes, Vulpes vulpes, Caribou, Rangifer tarandus, and Dall Sheep, Ovis dalli, in Alaska ROBERT 0. STEPHENSON, 1 DANIEL V. GRANGAARD,2 and JOHN BURCH3 1Alaska Department of Fish and Game, 1300 College Road, Fairbanks, Alaska, 99701 2Alaska Department of Fish and Game, P.O. Box 305, Tok, Alaska 99780 JNational Park Service, P.O. Box 9, Denali National Park, Alaska 99755 Stephenson, Robert 0., Daniel Y. Grangaard, and John Burch. 1991. Lynx, Fe/is lynx, predation on Red Foxes, Vulpes vulpes, Caribou, Rangifer tarandus, and Dall Sheep, Ovis dalli, in Alaska. Canadian Field-Naturalist 105(2): 255- 262. Observations of Canada Lynx (Fe/is lynx) predation on Red Foxes ( Vulpes vulpes) and medium-sized ungulates during winter are reviewed. Characteristics of I 3 successful attacks on Red Foxes and 16 cases of predation on Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) and Dall Sheep (Ovis dalli) suggest that Lynx are capable of killing even adults of these species, with foxes being killed most easily. The occurrence of Lynx predation on these relatively large prey appears to be greatest when Snowshoe Hares (Lepus americanus) are scarce. Key Words: Canada Lynx, Fe/is lynx, Red Fox, Vulpes vulpes, Caribou, Rangifer tarandus, Dall Sheep, Ovis dalli, predation, Alaska. Although the European Lynx (Felis lynx lynx) quently reach 25° C in summer and -10 to -40° C in regularly kills large prey (Haglund 1966; Pullianen winter. Snow depths are generally below 80 cm, 1981), the Canada Lynx (Felis lynx canadensis) and snow usually remains loosely packed except at relies largely on small game, primarily Snowshoe high elevations. -

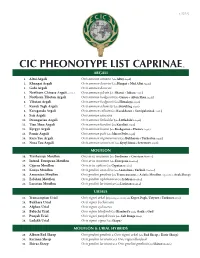

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

WDFW Washington State Recovery Plan for the Lynx

STATE OF WASHINGTON March 2001 LynxLynx RecoveryRecovery PlanPlan by Derek Stinson Washington Department of FISH AND WILDLIFE Wildlife Program Wildlife Diversity Division WDFW 735 In 1990, the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission adopted procedures for listing and delisting species as endangered, threatened, or sensitive and for writing recovery and management plans for listed species (WAC 232-12-297, Appendix C). The lynx was classified by the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission as a threatened species in 1993 (Washington Administrative Code 232-12-011). The procedures, developed by a group of citizens, interest groups, and state and federal agencies, require that recovery plans be developed for species listed as threatened or endangered. Recovery, as defined by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is “the process by which the decline of an endangered or threatened species is arrested or reversed, and threats to its survival are neutralized, so that its long-term survival in nature can be ensured.” This document summarizes the historic and current distribution and abundance of the lynx in Washington, describes factors affecting the population and its habitat, and prescribes strategies to recover the species in Washington. The draft state recovery plan for the lynx was reviewed by researchers and state and federal agencies. This review was followed by a 90 day public comment period. All comments received were considered in preparation of this final recovery plan. For additional information about lynx or other state listed species, contact: Manager, Endangered Species Section Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 600 Capitol Way N Olympia WA 98501-1091 This report should be cited as: Stinson, D. -

Canada Lynx Petition To

KRISTEN A. STILT KATHERINE A. MEYER Professor & Faculty Director Clinic Director CHRISTOPHER D. GREEN NICOLE E. NEGOWETTI Executive Director Clinical Instructor CEALLAIGH REDDY SARAH PICKERING Program Administrator Communications Manager PETITION To the Fish and Wildlife Service United States Department of the Interior May 13, 2021 To Revise the Special 4(d) Rule for Canada Lynx (lynx canadensis) to Rescind the Exceptions for the Captive Members of the Species Under the Endangered Species Act Lynx canadensis (photograph by the Fish and Wildlife Service) Prepared by Elizabeth MeLampy, J.D. Candidate Kate Barnekow, Clinical Fellow Katherine Meyer, Director Harvard Law School Animal Law & Policy Clinic TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 A. Petitioners ........................................................................................................................... 1 II. LEGAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................................... 2 A. The Endangered Species Act ............................................................................................. 2 B. The Canada Lynx Is Listed as a Threatened Species. ........................................................ 5 III. THE EXCEPTIONS FOR CAPTIVE CANADA LYNX ARE UNLAWFUL. .................. 6 A. Split-Listing Captive and Wild Members of a Species Exceeds the Service’s Authority Under the Act. ................................................................................................................ -

Life History Account for Himalayan Tahr

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group HIMALAYAN TAHR Hemitragus jemlahicus Family: BOVIDAE Order: ARTIODACTYLA Class: MAMMALIA M185 Written by: R. A. Hopkins Reviewed by: H. Shellhammer Edited by: J. Harris, S. Granholm DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY The tahr is an uncommon, yearlong resident of valley foothill hardwood and open grassland habitats on the Hearst Ranch, San Luis Obispo Co. (Barrett 1966). Probably no more than a few hundred of these introduced, goat-like animals live on the ranch. Native to Himalayan region, from Kashmir to Sikkim. SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Barrett (1966) suggested that tahr on the Hearst Ranch fed primarily on grasses, forbs, and to a lesser extent on browse, such as live oak, toyon, poison-oak, and laurel. Detailed food habits studies are lacking. Cover: Rock outcrops and cliffs appear to be almost essential for escape cover and for bedding. The tahr, which evolved in a cooler climate, may require shaded woodlands and north-facing slopes in summer. Reproduction: Rock outcrops and rugged cliffs offer protection from predators during breeding. Water: No data found. Pattern: Tahr use a mixture of valley foothill hardwoods and open grasslands, interspersed with rocky outcrops for protection. In native Himalaya habitat, rocky, wooded mountain slopes and rugged hills are preferred (Nowak and Paradiso 1983). SPECIES LIFE HISTORY Activity Patterns: Active yearlong; primarily diurnal. Seasonal Movements/Migration: Non-migratory in areas of moderate topographic relief, such as the Hearst Ranch. Home Range: Bachelor herds of different sizes and age-classes are found, as well as composite bands of mature females, immature bulls, and kids (Anderson and Henderson 1961). -

Lynx, the Snow Cat Others Being the Mountain Lion and the Bobcat

ReturnReturn OfOf TheThe SnowSnow CatCat TheThe ReintroductionReintroduction OfOf LynxLynx ToTo ColoradoColorado Acknowledgments Funding for this project was provided by US Fish & Wildlife Service Wildlife Conservation and Restoration Program Grant No R-11-1, Great Outdoors Colorado Trust Fund (GOCO), and the sportsmen of Colorado. The Colorado Division of Wildlife gratefully acknowledges the following individuals: Kevin S. McKelvey, USDA Forest Service, Field-test Educators: Rocky Mountain Research Station, Robert Lancaster, Walsh High School, Missoula, MT, for providing lynx occurrence Walsh, CO data from 1842 through 1998. Mark Little, Broomfield High School, Broomfield, CO For assistance in developing the field test: Lyn Neve, Swink High School, Swink, CO Anne Tweed, Senior Science Consultant, Camille Schiraldi, TH Pickens Technical McREL (Mid-continent Research for Center, Aurora, CO Education and Learning) Fran Sturgis, Adams City High School, Pam Van Scotter, Director, BSCS (Biological Commerce City, CO Sciences Curriculum Study) Center for Cherie Wyatt, Burlington Middle School, Curriculum Development. Burlington, CO Nicole Knapp, Science Educator, BSCS Debbie Yeager, Moffat County High School, Craig, CO Content Advisors and Reviewers: Graphic Design: Writers: Tanya Shenk, Senior Research Darren Eurich, State of Colorado Wendy Hanophy, DOW Biologist, Mammal Research Integrated Document Solutions (IDS) Jeff Keidel, Buena Vista High School, Jeff Rucks, Head of Education, DOW Buena Vista, CO Lisa Evans, Northeast Region Illustrations: