The Latin Prologues of John

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack About the Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack

The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack About The Origin of the New Testament by Adolf Harnack Title: The Origin of the New Testament URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/harnack/origin_nt.html Author(s): Harnack, Adolf (1851-1930) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Rights: Public Domain Date Created: 2005-04-20 General Comments: (tr. The Rev. J. R. Wilkinson) CCEL Subjects: All; Bible The Origin of the New Testament Adolf Harnack Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page. p. 1 Prefatory Material. p. 2 I. The Needs and Motive Forces that Led to the Creation of the New Testament. p. 12 § 1. How did the Church arrive at a second authoritative Canon in addition to the Old Testament?. p. 13 § 2. Why is it that the New Testament also contains other books beside the Gospels, and appears as a compilation with two divisions (ªEvangeliumº and ªApostolusº)?. p. 28 § 3. Why does the New Testament contain Four Gospels and not One only?. p. 38 § 4. Why has only one Apocalypse been able to keep its place in the New Testament? Why not severalÐor none at all?. p. 44 § 5. Was the New Testament created consciously? and how did the Churches arrive at one common New Testament?. p. 49 II. The Consequences of the Creation of the New Testament. p. 57 § 1. The New Testament immediately emancipated itself from the conditions of its origin, and claimed to be regarded as simply a gift of the Holy Spirit. It held an independent position side by side with the Rule of Faith; it at once began to influence the development of doctrine, and it became in principle the final court of appeal for the Christian life. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Epiphanius’ Alogi and the Question of Early Ecclesiastical Opposition to the Johannine Corpus By T. Scott Manor Ph.D. Thesis The University of Edinburgh 2012 Declaration I composed this thesis, the work is my own. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or qualification. Name……………………………….. Date……………………………………… 2 ABSTRACT The Johannine literature has been a cornerstone of Christian theology throughout the history of the church. However it is often argued that the church in the late second century and early third century was actually opposed to these writings because of questions concerning their authorship and role within “heterodox” theologies. Despite the axiomatic status that this so-called “Johannine Controversy” has achieved, there is surprisingly little evidence to suggest that the early church actively opposed the Johannine corpus. -

The Expository. Times. Recent

THE EXPOSITORY. TIMES. RECENT THEOLOGICAL LITERATURE. BOOKS. • Agrapha, DONEHOO (Index). BOOKS INDEXED. Akedia, CARROLL 133· · ACTON (Lord, as P1·0/ector), The Cambridge Modern History. Alchemy in Dante, CARROLL 404. Vol. II. The Reformation. , Alogi, DRUMMOND 334· BERNARD (J. H., as Editor), Psalms of Israel. Angel of Jehovah, DRIVER 184 . BRUCE (R., as Editor), Common Hope. Angels in N. T. Apocr., DONEHOO (Index), CAIRD (E.), Evolution of Theology in the Greek Philo- Annunciation, DONEHOO 25. sophers. ·Apocalypses, Jewish, MUIRHEAD 57-95. CARR (A.), Hone Biblicre. · Apocalyptic Literature of N. T., JULICHER 256-291~· CARROLL (J. S. ), Exiles of Eternity. Apostolic Age, Religion, HARNAC.K 155 ff. DAVIDSON (A. B.), Old T~stament Prophecy. Aristotle, Theology, CAIRD i. 260-382, ii. 1-30. DAVIS (N. K. ), The Story of the Nazarene. Asceticism, HARNACK 81 ff. ' DICKIE (W. ), Christian Ethics of Social Life. Ass, associated with Christ, HERFORD 154, 2II: DONEHOO (J. de Q.), Apocryphal and Legendary' Life of. " Worship, HERFORD 154· Christ. · Assyria and Israel, PINCHES 327 ff. DRIVER (S. R. ), Book of Genesis. Astronomy, the New, WALLACE 24-46. DRUMM?ND (J.), Character and Authorship of the Fourth Aton~ment in Christ's Death, HARNACK 159 ff. Gospel. Attention, HASLETT 133 ff. DRURY (T. W.), Confession and Absolution. Attrition, DRURY 103 ff. FITZPATRICK (J.), Characteristics from Faber's Writings. Auricular Confession, DRURY 14 ff. FL)i:W (J.), Studies in Browning. Avarice in Dante, CARROLL 110-125. HAIGH (H.), Some Leading Ideas of Hinduism. ·Babel, Tower, DRIVER I36f. HARNACK (A.), What is Christianity? (3rd Edition). Babylon and the Bible, PINCHES 525 ff. -

The Book of Revelation (Apocalypse)

KURUVACHIRA JOSE EOBIB-210 1 Student Name: KURUVACHIRA JOSE Student Country: ITALY Course Code or Name: EOBIB-210 This paper uses UK standards for spelling and punctuation THE BOOK OF REVELATION (APOCALYPSE) 1) Introduction Revelation1 or Apocalypse2 is a unique, complex and remarkable biblical text full of heavenly mysteries. Revelation is a long epistle addressed to seven Christian communities of the Roman province of Asia Minor, modern Turkey, wherein the author recounts what he has seen, heard and understood in the course of his prophetic ecstasies. Some commentators, such as Margaret Barker, suggest that the visions are those of Christ himself (1:1), which He in turn passed on to John.3 It is the only book in the New Testament canon that shares the literary genre of apocalyptic literature4, though there are short apocalyptic passages in various places in the 1 Revelation is the English translation of the Greek word apokalypsis (‘unveiling’ or ‘uncovering’ in order to disclose a hidden truth) and the Latin revelatio. According to Adela Yarbro Collins, it is likely that the author himself did not provide a title for the book. The title Apocalypse came into usage from the first word of the book in Greek apokalypsis Iesou Christon meaning “A revelation of Jesus Christ”. Cf. Adela Yarbro Collins, “Revelation, Book of”, pp. 694-695. 2 In Codex Sinaiticus (4th century), Codex Alexandrinus (5th century) and Codex Ephraemi (5th century) the title of the book is “Revelation of John”. Other manuscripts contain such titles as, “Revelation of John, the one who speaks about God”, “Revelation of Saint John, the one who speaks about God”, “Revelation of John, the one who speaks about God, [the] evangelist” and “The Revelation of the Apostle John, the Evangelist”. -

Epiphanius of Salamis and the Antiquarian's Bible

Epiphanius of Salamis and the Antiquarian’s Bible Andrew S. Jacobs Journal of Early Christian Studies, Volume 21, Number 3, Fall 2013, pp. 437-464 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/earl/summary/v021/21.3.jacobs.html Access provided by Claremont College (19 Sep 2013 14:24 GMT) Epiphanius of Salamis and the Antiquarian’s Bible ANDREW S. JACOBS Compared to more philosophical biblical interpreters such as Origen, Epi- phanius of Salamis often appears to modern scholars as plodding, literalist, reactionary, meandering, and unsophisticated. In this article I argue that Epiphanius’s eclectic and seemingly disorganized treatment of the Bible actually draws on a common, imperial style of antiquarianism. Through an ex- amination of four major treatises of Epiphanius—his Panarion and Ancoratus, as well as his lesser-studied biblical treatises, On Weights and Measures and On Gems—I trace this antiquarian style and suggest that perhaps Epiphanius’s antiquarian Bible might have resonated more broadly than the high-flown intellectual Bible of thinkers like Origen. INTRODUCTION: THE ANTIQUARIAN BIBLE In the mid-nineteenth century, a London print-seller named John Gibbs cut apart a two-volume illustrated Bible and began reassembling it. He inserted close to 30,000 prints, etchings, and woodcuts to illustrate the biblical passages, and then rebound the results. By the time he finished, his Bible had ballooned to sixty extra-large volumes, known today as the “Kitto Bible.”1 Gibbs’s extra-illustrated Bible was one of many so-called “Grangerized” volumes that circulated in the mid-eighteenth to early- twentieth centuries, books on various topics elaborately reconstituted as part gentlemanly past-time, part obsessive one-upmanship, part strange bibliomania.2 Gibbs’s extra-illustrated Bible borders on the excessive: one 1. -

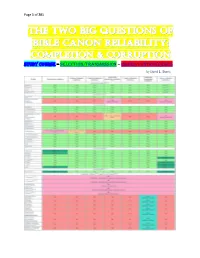

Selection/Transmission – Issues/Controversies by David L

Page 1 of 201 STUDY COURSE – selection/transmission – issues/controversies by David L. Burris Page 2 of 201 Page 3 of 201 Page 4 of 201 The History Of Canon: “Which Books Belong?” The Divine Assurance Of 2 Timothy 3:16,17 1. The significance of this study is readily seen. a. There has to be a normative standard by which man can know the Divine will. b. The consequences of Scriptural inspiration are dramatic – IF Scriptures are God-given, then they are authoritative! IF Scriptures are not God-given, then our faith rests upon uncertainty. IF Scriptures are only partially inspired, then we are left perplexed without an acceptable way to know what is the Divine will (or even if there is a “divine will”!). c. If there is no normative standard in religion, then there will be chaos. This chaos will testify against the God we know from the Scriptures. Thus, the very existence of the God of the Bible is impacted by this topic! d. Sincere hearts will be the target of this issue. Some accept only 66 Books as inspired, others accept more, others accept less – who is right? We must do all we can to determine which books are from God (Jn 12:48). e. In essence this study series focuses attention upon the most significant doctrine in the Christian’s faith. 2. 2 Timothy 3:16-17 offers us the Divine assurance concerning the trustworthiness of God’s Scripture. a. The passage analyzed and discussed. 1) This is known as the “classic text” for biblical inspiration. -

(D.Otes A.Nb [Totices. the Authorized Version Is Dropped : It Was a Use MR

.316 THE EXPOSITORY TIMES. the esoteric teachings of the Kabbala than to the Ashkenazic congregations of Great Britain and the Talmud. 1 ' British Empire, in Singer's .convenient edition. In what follows we shall take for our text-book, 1 The Authorized Daily Prayer- Book (Hebrew and . .as being most pnidically useful for our purpose, English), published by Eyre & Spohiswoode. the German minhag, as it is used among the (To be continued.) ______ ...,.., _____ _ Professor Thatcher of Mansfield College, Oxford. (D.otes a.nb [totices. The Authorized Version is dropped : it was a use MR. ALLENSON's ' Handy Theological Library' is less swelling of the bulk of the book. Judges does excellent evidence that there · are theological as not need a new commentary so cryingly as some well as other masterpieces which may be bound other books of the Old Testament ; for· we have in leather and sold at a small price. Phillips Moore and Black, a big and a little, both excellent. Brooks' Lectures on Preaching 1s one of the Still Mr. Thatcher is thoroughly furnished, 'and he volumes. It costs 3s. net. can see things for himself. · Messrs. A. & C. Black have published a sixpenny Messrs. Longmans have published a remarkably edition of Professor Percy Gardner's A Historic cheap (3s. 6d. net) edition of the late Bishop of View of the New Testament. It is very well Oxford's Ordination Addresses. printed. The Principal of the Church of Scotland Train The story of the C.M.S. and C.E.Z.M.S. mis ing College in Glasgow is a literary enthusiast. -

Lee Martin Mcdonald, "The Integrity of the Biblical Canon in Light of Its

Lee Martin McDonald, “The Integrity of the Biblical Canon in Light of Its Historical Development,” Bulletin for Biblical Research 6 (1996): 95-132. The Integrity of the Biblical Canon in Light of Its Historical Development Lee Martin Mcdonald First Baptist Church Alhambra, California [p.95] The following essay argues that the final fixing of the Hebrew Scriptures and the Christian biblical canon did not emerge until the middle to the late fourth century, even though the long process that led to the canonization of the Hebrew scriptures began in the sixth or fifth century BCE and of the New Testament scriptures in the second century CE. Pivotal in the arguments for an early dating of the Hebrew Scriptures is the lack of unequivocal evidence for the fixation of the Old Testament canon in the time before Christ but also the emergence of canonical lists of scriptures only in the fourth century CE. It is also argued that the Muratorian Fragment originated in the middle of late fourth century CE. The paper concludes with a discussion of viability of the traditional criteria of canonicity and whether these criteria should be reapplied to the biblical literature in light of more recent conclusions about authorship, date, theological emphasis, and widespread appeal in antiquity. Key Words: Canon of Scripture, Muratorian Fragment, early Patristics I. Introduction For the last generation or so there has been a growing interest in the formation of the Christian Bible and the viability of the current biblical canon. With little or no change in the -

Marcion, Papias, and 'The Elders'

134 THE JOURNAL OF THEOLOGICAL STUDIES MARCION, PAPIAS, AND 'THE ELDERS'. THE scholarly world will receive with exceptional interest Dr Harnack's latest contribution to the series of Texte und Untersuchungen (xlv, 1 1921). In this monograph on Marcion the veteran Church historian returns to the field of his earliest studies ; for to Dr Harnack, as the sub-title informs us, the study of Marcion is but an approach to that of ' the Founding of the Catholic Church '. Like other critics and historians Dr Harnack perceived from the outset the strategic position occupied by the great heretic. He adds materially to the careful work of Zahn by a new reconstruction of Marcion's text of Luke and the ten greater Epistles of Paul, and makes us much more largely his debtors by collecting the remains of the Antitheses in which Marcion defended his critical work. The reconstructions form the nucleus of a volume of some 65o pages octavo, and far surpass all material till now available. The chief service of the book will be its aid in enabling us to understand the work of the man upon whom the Church in the second century looked as in the sixteenth Rome looked upon Luther. If we limit ourselves for the present to the contrasted figures of Marcion and Papias it is not that we fail to appreciate Dr Harnack's guidance in other parts of the field, but that we think there is danger at this point lest the student be led astray. The present article, accordingly, is offered not so much in valuation of a work whose authorship alone is sufficient guarantee, as in the interest of caution against a certain too hasty inference of the distinguished Church historian, the adoption of which would seriously affect the issue in other important fields. -

By Philip Schaff VOLUME 1. First Period

a Grace Notes course History of the Christian Church By Philip Schaff VOLUME 1. First Period – Apostolic Christianity 1 Chapter 12: The New Testament 1 Editor: Warren Doud History of the Christian Church VOLUME 1. First Period – Apostolic Christianity Contents Volume 1, Chapter 12. The New Testament .................................................................................3 1.74 Literature. .................................................................................................................................. 3 1.75 Rise of the Apostolic Literature. ................................................................................................ 3 1.76 Character of the New Testament. ............................................................................................. 4 1.77 Literature on the Gospels. ......................................................................................................... 6 1.78 The Four Gospels. ...................................................................................................................... 8 1.79 The Synoptists. ......................................................................................................................... 11 1.80 Matthew. ................................................................................................................................. 20 1.81 Mark. ........................................................................................................................................ 25 1.82 Luke. ........................................................................................................................................ -

The Origin of the New Testament

The Origin of the New Testament Author(s): Harnack, Adolf (1851-1930) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: For Harnack, applying the methods of historical criticism to the Bible signified a return to true Christianity, which had become mired in unnecessary and even damaging creeds and dogmas. Seeking out what ªactually happened,º for him, was one way to strip away all but the foundations of the faith. In The Origin of the New Testament, Harnack explores the early history of the biblical canonÐhow it came to be what it is, and why. In particular, he explores the ideologies driving people to accept some texts as biblical cannon and not oth- ers. Controversially, Harnack finds some of these ideologies anything but Christian, and he hints that a re-evaluation of what the church considers canonical is necessary. Kathleen O'Bannon CCEL Staff i Contents Title Page 1 Prefatory Material 2 I. The Needs and Motive Forces that Led to the Creation of the New Testament 9 § 1. How did the Church arrive at a second authoritative Canon in addition to 11 the Old Testament? § 2. Why is it that the New Testament also contains other books beside the Gospels, 31 and appears as a compilation with two divisions (“Evangelium” and “Apostolus”)? § 3. Why does the New Testament contain Four Gospels and not One only? 44 § 4. Why has only one Apocalypse been able to keep its place in the New 52 Testament? Why not several—or none at all? § 5. Was the New Testament created consciously? and how did the Churches 58 arrive at one common New Testament? II. -

The Muratorian Fragment: the State of Research

JETS 57/2 (2014) 231–64 THE MURATORIAN FRAGMENT: THE STATE OF RESEARCH ECKHARD J. SCHNABEL* The fragmentary document known as “Canon Muratori” contains the oldest list of books of the NT. This essay will present the state of research regarding the Fragment, with particular attention to its date as wEll as its historical and theologi- cal significance. I. THE FRAGMENT The Muratorian Fragment consists of 85 lines; the beginning and probably the end are missing. The Fragment was discovered by Ludovico Antonio Muratori (1672–1750), an archivist and librarian at Modena, in the year 1700 in a manuscript in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan (Cod. Ambr. I 101 sup.), consisting of 76 leaves of coarse parchment. MuratOri publishEd thE FragmEnt in 1740 in thE third volume of his six-volume collection OF essays entitled Antiquitates italicæ mediiævi, in Dissertatio XLIII (cOls. 807–880) undEr thE hEading “De Literarum Statu, neglectu, & cultura in Italia post Barbaros in eam invEctos usque ad Annum Christi Millesi- mum Centesimum.”1 The manuscript originally bElonged to thE mOnastery at BobbiO in thE TrEb- bia River valley southwest of Piacenza in northern Italy. The manuscript contains a statement of Ownership by thE BObbiO mOnastEry: liber sti columbani de bobbio/Iohis grisostomi.2 ThE manuscript cOntains sEvEral thEOlogical treatisEs of thrEE thEOlogians * Eckhard J. SchnabEl is Mary F. ROckEFEllEr Distinguished Professor of NT Studies at Gordon- Conwell Theological Seminary, 130 EssEx StrEEt, SOuth HamiltOn, MA 01982. 1 LudOvicO AntOniO MuratOri, “DE LitErarum Statu, nEglEctu, & cultura in Italia pOst BarbarOs in eam invectos usquE ad Annum Christi Millesimum Centesimum,” in Antiquitates italicæ mediiævi: sive disser- tationes de moribus, ritibus, religione, regimine, magistratibus, legibus, studiis literarum, artibus, lingua, militia, nummis, principibus, libertate, servitute, fœderibus, aliisque faciem & mores italici populi referentibus post declinationem Rom.