The New Radio: How Public Radio Became Journalistic Podcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

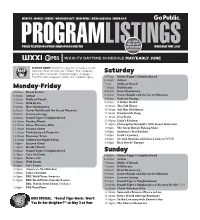

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 100 PODCASTS by DOWNLOADS Podcasts Ranked by Average Weekly Downloads in the United States Reporting Period: March 16 - April 12, 2020

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 100 PODCASTS BY DOWNLOADS Podcasts Ranked by Average Weekly Downloads in the United States Reporting Period: March 16 - April 12, 2020 # OF NEW RANK PODCAST PODCAST NETWORK SALES REPRESENTATION EPISODES CHANGE 1 NPR News Now NPR National Public Media 672 0 2 Up First NPR National Public Media 30 h2 3 The Ben Shapiro Show Cumulus Media/Westwood One Cumulus Media/Westwood One 22 0 4 My Favorite Murder with Karen Kilgariff Stitcher Midroll 9 i2 and Georgia Hardstark 5 Planet Money NPR National Public Media 11 h3 6 NPR Politics NPR National Public Media 21 h1 7 Fresh Air NPR National Public Media 24 i1 8 Pod Save America RADIO.COM/Cadence13 Cadence 13 8 h1 9 Dateline NBC NBC News Wondery Brand Partnerships 13 i4 10 Indicator from Planet Money NPR National Public Media 20 h3 11 Hidden Brain NPR National Public Media 4 i1 12 Fox News Radio Newscast FOX News Podcasts FOX News Podcasts 672 h4 13 TED Radio Hour NPR National Public Media 5 h1 14 Office Ladies Stitcher Midroll 4 i3 15 How I Built This NPR National Public Media 6 0 16 Wait Wait... Don't Tell Me! NPR National Public Media 5 h5 17 The Dan Bongino Show Cumulus Media/Westwood One Cumulus Media/Westwood One 21 i5 18 Freakonomics Radio Stitcher Midroll 5 h1 19 The Rachel Maddow Show NBC News Wondery Brand Partnerships 21 h1 20 Unlocking Us with Brené Brown RADIO.COM/Cadence13 Cadence13 7 New 21 Conan O’Brien Needs A Friend Stitcher Midroll 4 i3 22 Oprah’s SuperSoul Conversations Stitcher Midroll 4 i5 23 VIEWS with David Dobrik and Jason RADIO.COM/Cadence13 Cadence13 -

PARTNERS in Hope and Discovery Where the Power of Childhood Meets the Power of Research

PARTNERS in Hope and Discovery Where the power of childhood meets the power of research 2016 ANNUAL REPORT WHERE BREAKTHROUGHS HAPPEN The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the world’s premier biomedical research institution—and the breakthroughs that happen here are the first steps toward eradicating diseases, easing pain, and making better lives possible. None Inn residents of these medical advances would be participated possible without the people who drive them: children, families and caregivers, in 283 clinicians and staff—the community The CLINICAL Children’s Inn brings together. The Inn TRIALS provides relief, support, and strength to at the NIH these pioneers whose participation in in FY16 medical trials at the NIH can change the story for children around the world. Inn residents are a part of pediatric protocols in 15 of the 27 INSTITUTES and CENTERS at the NIH On the cover: Inn resident Reem, age 7 from Egypt, with her NIH physician, Dr. Neal Young. She is being treated for aplastic anemia at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. As partners in discovery and care, OUR VISION we strive for the day when no family endures the heartbreak of a seriously ill child. Letter from the Chair of the Board and Chief Executive Officer The Inn’s Board of Directors had an eventful We are so grateful to you: our donors, volunteers, year. We have worked diligently to restructure and friends, who help The Children’s Inn make a and prepare The Inn for the future, and recently profound impact on the lives of the NIH’s young- welcomed some talented new members to our est patients. -

As General Managers of Public Radio Stations That Serve Millions of Americans in Communities Large and Small, Urban and Rural And;

As General Managers of Public Radio stations that serve millions of Americans in communities large and small, urban and rural and; As Producers of local, regional and national content aired by stations throughout the nation committed to telling the evolving story of America, its proud history, and its committed citizens; We are writing to express our grave concern regarding the House legislation that would prohibit stations from using any Federal funds to pay for national programming and would eliminate CPB’s Program Fund. By prohibiting the use of Federal funds in any national programming, and in particular, by eliminating the CPB Program Fund, millions of Americans will be deprived of critical national and international news, information and cultural programming that cannot be found elsewhere. Local public radio stations will no longer reliably provide the community information and context so necessary to cities and towns challenged by change and faltering economies. Institutions and projects at risk include: - Radio Bilingüe’s national program service, public radio’s principal source of Latino programming - Koahnik Public Media’ Native Voice 1, public radio’s principal source of Native American programming - Youth Media, the California-based media network of young audio and video producers and a key source of a youth voice in the mass media - The Public Insight Network, American Public media’s expanding project to bring citizen experts into public radio journalism - Independent producers who depend upon the Program Fund for money to support production of series such as StoryCorps and This I Believe - Independent organizations dedicated to innovation, training, and excellence in journalism such as the Public Radio Exchange and the Association of Independents in Radio. -

TAL Distribution Press Release

This American Life Moves to Self-Distribute Program Partners with PRX to Deliver Episodes to Public Radio Stations May 28, 2014 – Chicago. Starting July 1, 2014, Chicago Public Media and Ira Glass will start independently distributing the public radio show This American Life to over 500 public radio stations. Episodes will be delivered to radio stations by PRX, The Public Radio Exchange. Since 1997, the show has been distributed by Public Radio International. “We’re excited and proud to be partners now with PRX,” said Glass. “They’ve been a huge innovative force in public radio, inventing technologies and projects to get people on the air who’d have a much harder time without them. They’re mission- driven, they’re super-capable and apparently they’re pretty good with computers.” “We are huge fans of This American Life and are thrilled to support their move to self-distribution on our platform,” said Jake Shapiro, CEO of PRX. “We’ve had the privilege of working closely with Ira and team to develop This American Life’s successful mobile apps, and are honored to expand our partnership to the flagship broadcast.” This American Life will take over other operations that were previously handled by PRI, including selling underwriting and marketing the show to stations. The marketing and station relations work will return to Marge Ostroushko, who did the job back before This American Life began distribution with PRI. This American Life, produced by Chicago Public Media and hosted by Ira Glass, is heard weekly by 2.2 million people over the radio. -

The Guide Your Connection to Spokane Public Radio Name(S) ______Volume 40 / No

Spokane Public Radio Membership and Donation Form Annual or additional contributions to Spokane Public Radio are always welcome. Mail to: Spokane Public Radio,1229 N. Monroe St., Spokane, WA 99201 THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT The Guide Your Connection to Spokane Public Radio Name(s) ___________________________________________________________________ Volume 40 / No. 2 April to June 2020 Address ___________________________________________________________________ SPR: The Information, News, & Entertainment Day Phone ( ) __________________ Evening Phone ( ) _____________________ You Need E-Mail ____________________________________________________________________ A note from Cary Boyce, President and General Manager Type of Gift/Pledge Dear Listeners, □ New membership □ Extra Gift □ Renewing Member □ Payment on Existing Pledge First, thank you for your ongoing support. These are unprecedented times Donation Amount $ ____________________________ in public radio as they are across the nation, and in our communities. At SPR we are doing our best to bring you news and information you can Payment Option rely on and use, in as timely a manner as possible. News from around the □ Sustaining Membership - ongoing monthly gift with automatic membership renewal nation, the state, and world—from NPR and BBC and our own reporters—is □ Credit/Debit card (see below) □ Auto Bill Pay from my bank brought to your cars and living rooms through SPR. It’s truly a great honor to Part of the NPR network □ Full payment enclosed □ First payment of $ ________________ enclosed work with such selfless and diligent colleagues here and around the world. The COVID-19 virus has changed the way SPR operates. Several staff □ Monthly: __________ months for $ ________________ per month □ EFT - for Sustaining monthly members are working from home as they can, even as others hold down the Pledge securely on-line: WA fort in our studios. -

Radiowaves Will Be Featuring Stories About WPR and WPT's History of Innovation and Impact on Public Broadcasting Nationally

ON AIR & ONLINE FEBRUARY 2017 Final Forte WPR at 100 Meet Alex Hall Centennial Events Internships & Fellowships Featured Photo Earlier this month, WPR's To the Best of Our Knowledge explored the relationship between love WPR Next" Initiative Explores New Program Ideas and evolution at a sold- out live show in Madison, We often get asked, "Where does WPR come up with ideas for its sponsored by the Center programs?" First and foremost, we're inspired by you, our listeners for Humans in Nature. and neighbors around the state. During our 100th year, we're looking Excerpts from the show, to create the public radio programs of the future with a new initiative which included storyteller called WPR Next. Dasha Kelly Hamilton (pictured), will be We're going to try out a few new show ideas focused on science, broadcast nationally on pop culture, life in Wisconsin, and more. You can help our producers the show later this month. develop these ideas by telling us what interests you about these topics. Sound Bites Do you love science? What interests you most ---- do you wonder about new research in genetics, life on other planets, or ice cover on Winter Pledge Drive the Great Lakes? What about pop culture? What makes a great Begins February 21 book, movie or piece of music, and who would you like to hear WPR's winter interviewed? How about life in Wisconsin? What do you want to membership drive is know about our state's culture and history? What other topics would February 21 through 25. -

Thesis a Uses and Gratification Study of Public Radio Audiences

THESIS A USES AND GRATIFICATION STUDY OF PUBLIC RADIO AUDIENCES Submitted by Scott D. Bluebond Speech and Theatre Arts Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring, 1982 COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY April 8, 1982 WE HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER OUR SUPERVISION BY Scott David Bluebond ENTITLED A USES AND GRATIFICATIONS STUDY OF PUBLIC RADIO AUDIENCES BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING IN PART REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts Committee on Graduate Work ABSTRACT OF THESIS A USES AND GRATIFICATION STUDY OF PUBLIC RADIO AUDIENCES This thesis sought to find out why people listen to public radio. The uses and gratifications data gathering approach was implemented for public radio audiences. Questionnaires were sent out to 389 listener/contrib utors of public radio in northern Colorado. KCSU-FM in Fort Collins and KUNC-FM in Greeley agreed to provide such lists of listener/contributors. One hundred ninety-two completed questionnaires were returned and provided the sample base for the study. The respondents indicated they used public radio primarily for its news, its special programming, and/or because it is entertaining. Her/his least likely reasons for using public radio are for diversion and/or to trans mit culture from one generation to the next. The remain ing uses and gratifications categories included in the study indicate moderate reasons for using public radio. Various limitations of the study possibly tempered the results. These included the sample used and the method used to analyze the data. Conducting the research necessary for completion of this study made evident the fact that more i i i research needs to be done to improve the uses and gratifica- tions approach to audience analysis. -

FY 2016 and FY 2018

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Appropriation Request and Justification FY2016 and FY2018 Submitted to the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee and the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee February 2, 2015 This document with links to relevant public broadcasting sites is available on our Web site at: www.cpb.org Table of Contents Financial Summary …………………………..........................................................1 Narrative Summary…………………………………………………………………2 Section I – CPB Fiscal Year 2018 Request .....……………………...……………. 4 Section II – Interconnection Fiscal Year 2016 Request.………...…...…..…..… . 24 Section III – CPB Fiscal Year 2016 Request for Ready To Learn ……...…...…..39 FY 2016 Proposed Appropriations Language……………………….. 42 Appendix A – Inspector General Budget………………………..……..…………43 Appendix B – CPB Appropriations History …………………...………………....44 Appendix C – Formula for Allocating CPB’s Federal Appropriation………….....46 Appendix D – CPB Support for Rural Stations …………………………………. 47 Appendix E – Legislative History of CPB’s Advance Appropriation ………..…. 49 Appendix F – Public Broadcasting’s Interconnection Funding History ….…..…. 51 Appendix G – Ready to Learn Research and Evaluation Studies ……………….. 53 Appendix H – Excerpt from the Report on Alternative Sources of Funding for Public Broadcasting Stations ……………………………………………….…… 58 Appendix I – State Profiles…...………………………………………….….…… 87 Appendix J – The President’s FY 2016 Budget Request...…...…………………131 0 FINANCIAL SUMMARY OF THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING’S (CPB) BUDGET REQUESTS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016/2018 FY 2018 CPB Funding The Corporation for Public Broadcasting requests a $445 million advance appropriation for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This is level funding compared to the amount provided by Congress for both FY 2016 and FY 2017, and is the amount requested by the Administration for FY 2018. -

THE FIRST FORTY YEARS INTRODUCTION by Susan Stamberg

THE FIRST FORTY YEARS INTRODUCTION by Susan Stamberg Shiny little platters. Not even five inches across. How could they possibly contain the soundtrack of four decades? How could the phone calls, the encounters, the danger, the desperation, the exhilaration and big, big laughs from two score years be compressed onto a handful of CDs? If you’ve lived with NPR, as so many of us have for so many years, you’ll be astonished at how many of these reports and conversations and reveries you remember—or how many come back to you (like familiar songs) after hearing just a few seconds of sound. And you’ll be amazed by how much you’ve missed—loyal as you are, you were too busy that day, or too distracted, or out of town, or giving birth (guess that falls under the “too distracted” category). Many of you have integrated NPR into your daily lives; you feel personally connected with it. NPR has gotten you through some fairly dramatic moments. Not just important historical events, but personal moments as well. I’ve been told that a woman’s terror during a CAT scan was tamed by the voice of Ira Flatow on Science Friday being piped into the dreaded scanner tube. So much of life is here. War, from the horrors of Vietnam to the brutalities that evanescent medium—they came to life, then disappeared. Now, of Iraq. Politics, from the intrigue of Watergate to the drama of the Anita on these CDs, all the extraordinary people and places and sounds Hill-Clarence Thomas controversy. -

The Politics of Podcasting

Sheridan College SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence Faculty Publications and Scholarship School of Communication and Literary Studies 12-13-2008 The olitP ics of Podcasting Jonathan Sterne McGill University Jeremy Morris McGill University Michael Brendan Baker McGill University, [email protected] Ariana Moscote Freire McGill University Follow this and additional works at: https://source.sheridancollege.ca/fhass_comm_publ Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons SOURCE Citation Sterne, Jonathan; Morris, Jeremy; Baker, Michael Brendan; and Freire, Ariana Moscote, "The oP litics of Podcasting" (2008). Faculty Publications and Scholarship. 1. https://source.sheridancollege.ca/fhass_comm_publ/1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Communication and Literary Studies at SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Scholarship by an authorized administrator of SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FCJ087 The Politics of Podcasting Jonathan Sterne, Jeremy Morris, Michael Brendan Baker, Ariana Moscote Freire Department of Art History & Communication Studies, McGill University At the end of 2005, the New Oxford American Dictionary (NOAD) selected ‘podcast’ as its word of the year. Evidently, enough people were making podcasts, listening to them, or at least uttering the word podcast in everyday contexts to warrant the accolade. Despite occasioning a media sensation, the actual extent of podcasting is still unknown. According to a PEW Internet and American Life survey (Rainie and Madden, 2005) – still the most substantive publication about podcasting trends – approximately 6 million of the 22 million U.S. -

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008: the Role of Greed, Fear, and Oligarchs Cate Reavis

09-093 Rev. March 16, 2012 The Global Financial Crisis of 2008: The Role of Greed, Fear, and Oligarchs Cate Reavis Free enterprise is always the right answer. The problem with it is that it ignores the human element. It does not take into account the complexities of human behavior.1 – Andrew W. Lo, Professor of Finance, MIT Sloan School of Management; Director, MIT Laboratory of Financial Engineering The problem in the financial sector today is not that a given firm might have enough market share to influence prices; it is that one firm or a small set of interconnected firms, by failing, can bring down the economy.2 – Simon Johnson, Professor of Entrepreneurship, MIT Sloan School of Management; Former Chief Economist, International Monetary Fund On October 9, 2007, the Dow Jones Industrial Average set a record by closing at 14,047. One year later, the Dow was just above 8,000, after dropping 21% in the first nine days of October 2008. Major stock markets in other countries had plunged alongside the Dow. Credit markets were nearing paralysis. Companies began to lay off workers in droves and were forced to put off capital investments. Individual consumers were being denied loans for mortgages and college tuition. After the nine-day U.S. stock market plunge, the head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had some sobering words: “Intensifying solvency concerns about a number of the largest U.S.-based and European financial institutions have pushed the global financial system to the brink of systemic meltdown.”3 1 Interview with the case writer, April 10, 2009.